|

|

| Neue Slowenische Kunst Marko Košan Retro-constructions: Who's afraid of totalitarian art's heritage? | |

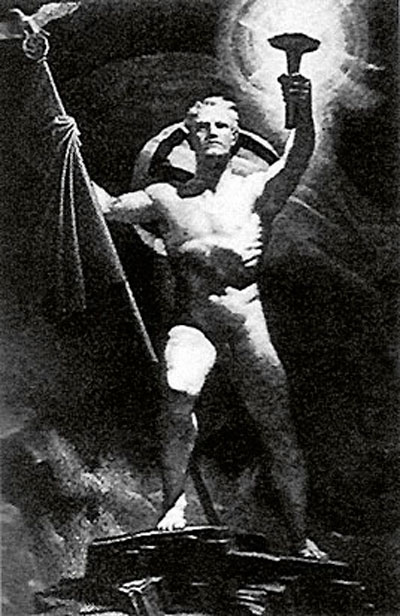

Richard Klein. Poster | |

| In the night of 26 September 1980 a poster with a subtly provocative symbol appeared on the walls of the Slovenian industrial town of Trbovlje. The poster showed a simple black cross accompanied by a single word: "Laibach". A second, less subtle, poster depicted an act of mutilation: the attacker was putting out the victim's eye with a knife. This one, too, provided no additional information apart from the word "Laibach". The two posters were announcing an exhibition and a concert by the group named Laibach, which were to be the group's first public appearance.

"Laibach" is the German name for the Slovenian capital Ljubljana, known as early as the Middle Ages, more widely used in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (the name first appeared in writing in 1144) and, of course, in the period of Nazi occupation during World War II. The cross referred to the Suprematist motifs of Kasimir Malevich, but was at the same time reminiscent of the black cross marking German combat vehicles and planes during World War II. The questionable associations evoked by the name and the symbol (as well as the cruelty depicted in the second poster) almost immediately led the authorities to remove the posters and ban the event. Since its first appearance Laibach's unconventional stance infected a number of art groups in various venues of expression and art engagement in Slovenia - in music, theatre, architecture, design and visual arts to be specific. In their daring and provocative play with totalitarian ideological concepts, always supported by well-deliberated theoretical discourse, they were formally and informally united in the community called Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK), and "sneaked" into numerous expressive media, including the "ideological constructions" such as Nation and State, and in the period of the decline of the Socialist doctrine in the iron-curtained Eastern Europe - prior to and heralding the fall of the Berlin Wall - accumulated a huge, almost unmanageable quantity of works with aesthetically recognisable, but, given the vagueness of its message, elusive statements which evoked (and still evoke) a wide variety of highly varied responses, myths and misunderstandings, confusion and fascination, rumours and accusations as well as serious critical reflection in Slovenia and in many foreign countries, where Laibach in the decade just before the end of the millennium made its name as one of the most recognisable phenomena of post-modernist art discourse in Europe. With their very first "anonymous" appearance in the conditions of Yugoslav Real Socialism and in the year marking the death of its long-term charismatic dictatorial leader Tito, when Laibach appeared only with their symbol and name, the group triggered off an avalanche of associations and reminiscences which are hard to harness, but could in fact be captured in three fundamental points: the art history framework of the early 20th century avant-garde (Malevich, Duchamp), the Slovenian national history framework (Laibach) put in the context of exclusive nationalist kitsch of the Heimat and Blut und Boden type, and the power of symbols and symbolic images as represented by the propaganda effect of posters exploited to the extreme. In the persiflage of the authoritarian stance, the artists belonging to the NSK movement appear without individual identity, always as a collective entity, as a merciless collective organism. The totalitarian credo of their (haughty) appearances has always been explicitly expressed in every one of their numerous written manifestos, such as: Laibach is an organism consisting of individuals who are its organs, these organs being subordinated to the whole, standing for the synthesis of its members' powers and endeavours. The goal, life and means of the group are higher - in terms of importance and duration - than the goals, lives and means of the individuals making it up. (NSK, Amok, Los Angeles, 1991) Laibach and NSK are therefore a "plural monolith", and the spreading of the cross as their fundamental symbol is the paradigm of denying identification with any art movement and artist as an individual. Their position is always ambiguous, arising from paradox and dissonance, which causes nervous and provocative tension, but on the other hand the confrontation of Socialist Realism and Nazi art evokes an energy which - in its destructive discursive power - was characteristic of both artistic avant-garde and totalitarian ideologies. The process of simultaneous sur-identification and deidentification and consequently of the inability to classify NSK within the contexts of contemporary art practices was in its very inception conceptualised by Laibach, the group which later made a name for itself as a highly successful and internationally acknowledged alternative music group, and confirmed by other NSK formations - such as Irwin (visual arts), Novi Kolektivizem (design), Gledališče Sester Scipion Nasice theatre, and later Rdeči Pilot and Noordung as well as NSK - Department for Pure and Practical Philosophy - which termed their creative impulses as "retrogarde" or "retroavant-garde", which, of course, is just another example of paradoxical dissociation, in this case derived from the notion of avant-garde as such. What the NSK artists describe as the "retro principle" is in fact a methodology with which they reject the procedures of a revolutionary transformation of the existing, which is the fundamental characteristic of any avant-garde, and exchange them for eclectic combinations of avant-garde art with pop elements and Nazi art, of Socialist Realism with conceptualism, of modernism with folk art and Slovenian impressionism as the paradigm of Slovenian early 20th century modern art "Instead of rejecting or transcending the past to which the avant-garde now belongs, NSK tries to reform the past and exploit its suppressed energies. NSK's intention is to open up new opportunities for the future, but no longer with the ‘year zero' of revolutionary negation, but with critical investigation and reformation of the existing material." (Alexei Monroe, Pluralni monolit: Laibach in NSK, Ljubljana 2003). NSK is a merciless mirror of the century which some call the totalitarian century. The terror and crimes inherent in some of the political regimes are hard to capture in memory as the basis of the moral imperative blindly repeating its "Never again!". When the interpreters of the 20th century traumas try to establish this memory, they withdraw it at the same time from any reflection, although it is clear that what was not intended - albeit a phenomenon of the past - will persist in the future as well. When we try to capture the essence of the last century, we realise that the memory is insufficient, as the most inconceivable voids caused by some of the most traumatic events (written about by a number of contemporary, particularly French philosophers including Lyotard, Wajcman and Badiou) cannot really be articulated. NSK's retro-principle hits exactly at the centre of this sore spot, being actively different: confrontations with the expressions of totalitarianism are offered to the audience in direct, sometimes shockingly disturbing form filled with anxiety and still aching wounds. It is very clear that, contrary to what is commonly believed, the prohibition of repetition derives from thought, and not from memory. "Art and totalitarianism doesn't exclude each other. Totalitarian regimes suppress illusion of individual revolutionary artistic freedom. LAIBACH KUNST is a principle of wilful renouncement of personal taste, judgement, conviction (..); free de-personalization, voluntary pledge towards ideology, unmasking and recapitulation of main-stream "ultra-modernism"..." Laibach, 1982 More on NSK, official web-site: www.nskstate.com | |

| go back | |