|

|

| Intelligent graffiti Krišs Salmanis, Artist A recording of Dan Perjovschi’s lecture with notes | |

| When I asked Dan Perjovschi about the key to his success, the Romanian artist, with most of the major shows and art venues already sitting comfortably in his creative biography, answered humbly. “Success is a relative term. I am not mainstream successful (no art magazine covers, no million dollar works, no superpower gallery, no brick-thick catalogue). [...] I am easy, not big budget, can come in a week, I need no work transport, no insurance and not much planning. But most of all, I’ve got the irony...” Had our conversation remained solely within the electronic realm, this could perhaps seem slightly irritating, like when you hear the well-to-do speaking of money. But luckily Perjovschi had been invited to Riga for the third instalment of the yearly Survival Kit arts festival, organized by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art. Part of his contribution was an artist’s lecture – well-polished by probably having been delivered a fair number of times already, but punctuated throughout by bursts of such sincere and infectious laughter, that by the end of the lecture the human person almost over-shadowed the professional. This performance was rich enough to need no further embellishment before publication. Therefore here is what he said. “I was invited to give a lecture. As usual, I will talk about myself. I am an artist who was born in Romania, and I come from a context that has a very poor knowledge of contemporary art. That and the communist situation was not exactly a recipe for success. Since then it has been a process of constant adaptation to the context, often with very few means, very little resources. That is why I have to be constantly there. If you are not showing for three months, you are gone. I was born in 1961, so I will be 50 this year. I was born the year they erected the Berlin wall. The wall is gone, I’m still standing. The political context has played a great role in my art. In 1993, shortly after the great changes, when the situation was very tough and I was very poor, one way to speak about it was to do body art. It was cheap and radical. But I did not like to do performance art that everybody else did, so I did a tattoo, which is a very boring performance. It went on for 20 or 30 minutes. It was an artisanal tattoo. At the time we didn’t have machines, it was not a popular thing. No superstar on the TV had tattoos then, now everybody has them. Back then it was the sign of an outcast – “jailer-sailor”. So I had the name of my country tattooed on my shoulder. As if I was owned by it. It was a performance to get space, to have some distance from my country. Usually I don’t like to represent anyone other than myself. This was a tactic to claim back my body, and not only. Ten years later, I erased it, again as a performance. If the making of the tattoo cost me a beer for the person working with the needle, then the taking out of it cost 2000 euros. This was in 2003, in Germany, as part of a very large show of art from the south of Europe, In the Gorges of the Balkans. It had the same task of creating a space between me and the new context: Romania was already on the path to becoming a member of the EU, it was part of NATO, the situation had changed dramatically after the year 2000. With this action I tried to find my place in the society I was living in. | |

Dan Perjovschi. 2011 Photo: Didzis Grodzs | |

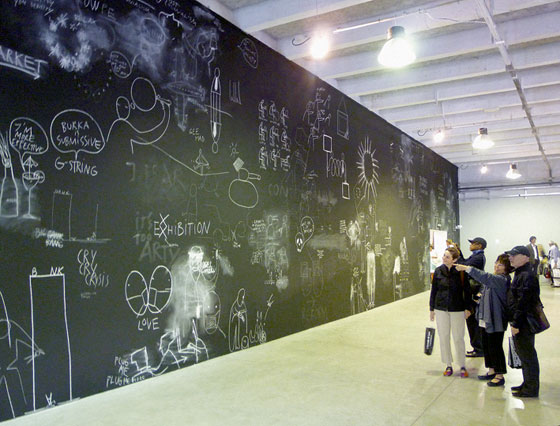

| This is a satellite image of Europe in 1985. [Showing a picture of Europe at night with the various degrees of illuminated cities all over it] What you see as a black hole near the Black Sea, that’s my country. I grew up in a culture of shortages. No money, nothing to eat, no soap, no toilet paper, no books, no knowledge, no passport. As a child I didn’t notice it – parents tend to protect their children from that. Besides, in the 60s it was still the rule of the liberal communists. Come the 80s and it was all tumbling down. The dictator materialized his dream of total power by building one of the largest buildings in the world while I started my becoming an artist. I attended a general school of art from the age of 10, then a secondary school of art, then art academy. Twelve years of painting still lifes. I learned to tell the truth when society was based on lies. So I grew up with a mistrust of ideology. The Ceausescu palace is the past, the present and the future of my country. The palace of the dictator became the parliament; what was once the symbol of dictatorship is now the symbol of democracy. Behind it the National Museum of Contemporary Art was founded, while in front of it pop concerts are organized. Every rockstar wants their picture taken with the huge structure in the background. From a symbol of people’s suffering it has become the ultimate spectacle. The largest building on the planet after the Pentagon... (Laughter) Romania is one of the few countries in the world where the dictator got gunned down. Most others die in peace, in political asylum in very rich countries. Nicolae Ceausescu was on the cover of ‘Time’ magazine in 1968 when he opposed the Russian invasion of Prague. Romania was the only member of the Warsaw Pact who did not support the invasion, and he was seen as a most tolerant and progressive person. Forty years later he was killed by his own people. How could something that started so well end up so bad? Ceausescu built a society of total control. For an artist to exhibit at a gallery he had to pass three censorship committees: your fellow artists, the cultural body of the city and then the Communist Party. Trying to avoid the communist reality I started making graphic images based on repetition, they were actually things that had nothing to do with nothing. A pattern of human beings. No composition, no colour, nothing. One piece that contained 50,000 portraits was made in 1993 and had a video camera constantly scanning it and projecting the portraits onto a screen. It was a work about the communist system of surveillance, but it fits the capitalistic situation equally well. But these kinds of large installations made it impossible for me to travel. Weight, insurance, transport – it was all beyond my reach. So I thought, if I continue doing these massive installation works, I will be trapped in my own context and my country will not be able to export me. I decided to start drawing directly onto the wall. In 1995 I did a show in New York where I drew a graph on the wall and filled each little square with a drawing of a little face. The work took a month. During the opening, visitors received erasers and were invited to rub out the faces. And they did! With passion. It was 1st December, Romanian National Day and AIDS day in America, but I realized this coincidence only later. It was the first piece to incorporate erasure, disappearance. For a week after the revolution in Romania we were all friends. We had won. But then what? The country split and we democratically fought. I am laughing now, but it was tragic. What was happening in the street was absolutely phenomenal. Every millimetre of democratic advancement in my country was fought out in the streets. Everything done in the galleries at that time was super boring. It couldn’t compete. We had our own Tiananmen Square with student protests against the neo-communist government crushed by miner paramilitary units imported from another region. We did not have Russian troops to blame, we had occupied ourselves. Since the gallery scene did not seem interesting, I joined the first independent weekly magazine in Romania (and maybe the last). It was run by intellectuals and I used it instead of a gallery. The texts were very sophisticated and my task was to make the newspaper more attractive. I had to illustrate the narrative, but the drawings had to be able to speak for themselves, too. I started in 1991 and have been doing the weekly illustrations till this day. So when I am asked about the political involvement of an artist, this is my involvement with society. I consider the magazine as a public space. I also make my own newspaper which I sometimes call my “eight page gallery”. I very much like this format. It is very permanent today and very temporary tomorrow. The group that ran this magazine were very vocal in politics from 1990 until 2000, and then they lost influence like many intellectual think-tanks all over Europe. In a way they gained freedom. Their initial task was to place Romania in Europe, now I think their function is to be a place of peace and quiet in a society where everything is tabloid. Everything sells, everything is spectacular. Nothing has any intellectual content whatsoever. Facebook is more intellectual than the press. For me it took ten years to come from the newspaper to the wall. Now I am drawing in all kinds of places, from the magnificent MACRO in Rome to an underground space in Chisinau, Moldova, from black walls like in Lyon Biennale to white walls like in Centre Pompidou in Paris. I do rough spaces like in Zollverein in Ruhr, Germany, and white cubes like Portikus in Frankfurt. Sometimes I draw on glass (the Bloomberg space in London). These drawings are not cartoons or graffiti, or some mixture. The best definition I have heard came from an old woman watching me drawing on a wall. She said, “Aaaaah, finally some intelligent graffiti”. (Laughter) The drawings are adaptable, I don’t need a kunsthalle, I have drawn on blackboards, but it can be the ceiling or even the benches you are sitting on. So I am liberated from the pressure of space that gives you authority. When they built the Sydney National Gallery in 18whatever, they had planned for a series of bas-reliefs on the facade, but they ran out of money. So I did some drawings in the empty places for the Biennale there. The style of drawing that I have developed allows me to say all kinds of things, even “RIGAGA”. This approach requires my physical presence, which means travelling. Today artists are difficult to catch, they are always doing a big show somewhere else. I think that everyone who has invited me deserves my time, my physical presence. It is exhausting, everybody in the artistic world wants to be the first to show you. But I want to come back, therefore my projects are being erased. It is like a deal between me, the curator and the public: we have the space together for a while. The practice of disappearance allows for the works to be reinterpreted. There are a number of standard situations. | |

Dan Perjovschi. Everyday Drawing. 10th Lyon Biennale. 2009 Photo from the private archive of Dan Perjovschi | |

| The first is like the biggest wall in the biggest museum of art in the world – MoMA in New York. I drew for days until it was complete, like a performance, with the visitors allowed to watch. When the show was over, the wall was painted over. The second situation is like in the contemporary art space in Castelló, northern Spain. They built a wall which then had to be broken down. With the destruction you gain freedom. Sometimes I draw in very public spaces, with chalk on the pavement, so when the rain comes... Or the drawings in the Romanian pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1999. They were done on the floor, so the audience had to step on them in order to see them. Thus the public accepted responsibility and became part of the creative process, even if it was destructive. In the international pavilion of the Biennale I made my drawings without fixing them, so the professionals who are trained to see, but do not look, wiped the drawings away with their coats during the opening reception by leaning against the walls. Another strategy was used at the Tate in Liverpool. There I had an enormous wall. I made some initial drawings and let the visitors carry on. The show lasted for three months and the audience drew. And they drew. And they drew. Initially I was very disappointed, because even though there are millions of intelligent people out there, the minute they have to convey their thoughts visually, they start doing really boring, standard things like “I love Jenny” or “F**k you”, or something. It is a problem, because visual language is common to us all. Every kid knows how to draw. Then they go to school where they are being taught, and they lose it. But over time, as the drawings became layered on top of each other, it started looking good. Most of them are at human height, but some people conquered more space by coming in groups and lifting each other to reach higher. I used the idea of erasure also in Paris, where I would come to the gallery and erase one of my drawings every day. So if you came towards the end of the show, you saw almost nothing. As if I were returning the space to the gallery in the shape I got it. So erasure really became part of my vocabulary. I can make a living by doing illustrations and drawings here and there, but I think if your works are bought, there is a special communication between the buyer, who decides to invest money in your work, and the artist. So I used linoleum to cover the floor of the Gregor Podnar Gallery in Berlin, Germany, and drew on it. If you liked the drawing, I would cut it out and sell it to you. Thus disappearance became a sign of success. Can you believe it? They bought such stuff. Today, you can be radical and smart, but still they will find a way to sell you. It becomes like a constant pas de deux between your independence and the world that knows how to pack, brand and sell you immediately. There are also a few permanent works, like in the Moderna museet in Stockholm, where I placed them inside the lockers. If you drop in a coin to open your locker, you have your own little exhibition. They have 128 lockers. I am also very proud of the work I did in the National Technical Library in Prague. | |

Dan Perjovschi. What Happened to Us? Museum of Modern Art, New York. 2007 Photo from the private archive of Dan Perjovschi | |

| Sometimes I send postcards. I was once invited to Kosovo, but couldn’t go. Now it is easy to go anywhere in the world, but it is the most difficult to visit your neighbours. So I sent them drawings by fax every day. Sometimes they did not have electricity, so some works got through, some didn’t. The fax machine became the curator! (Laughter) For another show, I sent a postcard every day during the three months prior to it. In the gallery they were exhibited as a pile and the gallery people would change the top postcard every day. In another space I could not draw on the walls, but they provided me with blackboards. They were enormously heavy and were stacked against a wall. The drawings were not fixed, so every time a buyer came to look at them, they were being devaluated – getting scratches and so on. But I am grateful to the galleries, because it is not easy to work with contemporary art. Despite the complicated job, they let me experiment.” At this point the batteries of my voice recorder expired. While I was wondering what to do next, Perjovschi spoke about his wife Lia’s art, which concentrates around the creation of the Contemporary Art Archive Center for Art Analysis as a data bank and a platform for institutional critique, as well as the Museum of Knowledge they both created in a purposebuilt two storey building that is meant to be always accessible. When asked about the progress of his everpresent sketchbook while in Riga, he replied that drawings spring up everywhere, but usually around fifty per cent of the drawings of a given show are new interpretations of earlier pieces. Will his future shows contain something that was drawn in Riga, too? Even if they do, we’ll have a hard time telling. Perjovschi’s art, which was born in a close relationship with Romania, is now thoroughly global. It can be pinned down to nowhere, but is understood everywhere. /Translator into English: Krišs Salmanis/ | |

| go back | |