|

|

| Logina’s constellation in the mists of myth Jānis Borgs, Art Critic Polemical thoughts on the legacy of Zenta Logina | |

| This artist is already a well-known name and requires no introduction. Zenta Logina (1908–1983) was a pioneer of Latvian abstractionism, one of the first and as such is part of our golden heritage of art. We were once again reminded of Logina’s sterling contribution to Latvia’s culture and history by an outstanding selection of paintings from her abstract period which were on display at the Gallery Alma. For this we have to thank two passionate curators, Astrīde Riņķe and Vilnis Vējš, as well as the Zenta Logina Foundation. This exhibition was a major event because we have not enjoyed such a rich array of her paintings for a long time. However, looking back at the period of Logina’s rediscovery and great achievements after 1987, the year her first big personal exhibition was held in Riga’s St. Peter’s Church, some confusion has arisen which, in the name of truth, should be addressed. If we re-read all that has been written about the artist since 1987, we see a common tendency to, at all costs, turn this classic modernist into a heroine who “suffered” under the abuses and restrictions imposed by the “Soviet regime”. This is especially evident in texts produced after the restoration of independence of Latvia. Unfortunately there appears to be an all too transparent attempt to use the prevailing political climate to exaggerate the tragic aspects in order to make Logina’s image and works seem even more significant to the public. | |

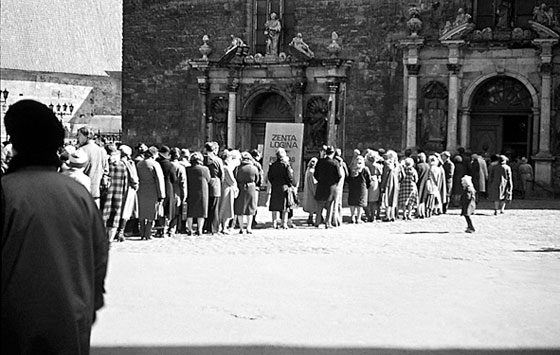

Visitors queueing up for Zenta Logina's personal exhibition in St.Peter's Church. 1987 | |

| Documents and testimonies relating to Logina are quite often interpreted somewhat superficially and subjectively, as if trying to create a “martyr” figure. However, if we examine the issue in depth and evaluate matters in the context of the period, it is clearly apparent that Zenta Logina was a vivid, strong personality who lived the ordinary life of a Latvian “Soviet artist”. There is nothing extraordinary except for her creative heroism in the field of abstract art, something no longer disputed by anyone. The mysterious apartment Once upon a time there was a grand, wealthy people’s apartment in central Riga with ornamented ceilings and parquet floors, and fireplaces and bay windows... Artist Zenta Knope-Logina moved into this Blaumaņa iela apartment just a month after the Reds took over the city from the Nazis in October 1944. The entire second half of her life, 39 years of the Soviet era, was spent in this communal apartment, often together with her sister Elīze Atāre (1915–1993), who Zenta sometimes referred to as her “little brother”. As with most Latvian artists, the priority in this dwelling was given to creative work, and the rooms were used as a painting and weaving workshop. Here, everyday existence mingled with artistic work. Looking at old photographs, we see the characteristic domestic arrangements of a Latvian lady intellectual of the mid-20th century, a style of living typical also of teachers, doctors and other educated people. These surroundings, with their “academically” folksy and slightly dilapidated elegance featuring floral tablecloths, ceramic vases, candlesticks, extensive collections of books on the shelves and paintings of flowers or landscapes on the walls, speak of the presence of a strong intellectual life. For years now, the sisters Zenta and Elīze have been leading another life in the hereafter, and their former “spiritual temple” is covered in dust, reigned over by the silence of an abandoned warehouse and the twilight sadness of a crypt. This is the temporary “refuge” of the Zenta Logina Foundation, which like an unwanted and abandoned pensioner is still lovingly cared for by cultural “nurse” Pēteris Ērglis and a few of his friends. The windows facing the street have been papered over: this heightens the extra-terrestrial mood. One might think that this has been done recently, out of concerns for security, but not so. It turns out that these papers were already in place when the sisters were alive, as if attempting to keep out the external world. Or perhaps this was born of a desire to isolate themselves from “Soviet reality?” However, the view outside the windows shows nothing particularly Soviet, just lots of noble classics of architecture. The blind windows could also symbolise a peculiar psychological condition. But most likely, though, there was a practical need for diffused northern light to improve the technical conditions in the workshop. Occasionally, the almost “autistic introversion” of the sisters in their virtually metaphysical life together as twins seems like a mystery. This may be the source of Zenta Logina’s cosmic visions. The mood of similar mental dramas may be found in Hitchcock’s films or the Russian classics Chekhov and Dostoyevsky, where intense spiritual tension drives a sensitive artistic soul to become estranged from reality and dwell in its own world, abandoning vacuous everyday disturbances in favour of its own chosen values. There is no shortage of examples like that in Latvian art. Many artists in many different periods have locked themselves away in their “ivory towers”: we may call to mind the monumental Ādolfs Zārdiņš and his “life within himself.” However, the pile of programmes for concerts, exhibitions and other events left in her old home indicate that Logina was not such an extreme “isolationist” at all. She did go out and socialised, but knew how to maintain her distance. The Foundations The spirituality of the Knope sisters was nurtured already in their childhood and youth. Zenta Logina was born in Riga in 1908 into the family of Kārlis Knope, a real man of Riga with drawing and draughtsmanship skills, and Karolīne Emīlija Kranāts, a woman from Valmiera. The father’s skills came in handy when the family ended up in Moscow as war refugees in 1915. Zenta could have grown up to be a right little “bourgeois mademoiselle”, but instead emerged as a bright, intelligent young woman. Or as Džemma Skulme aptly described her: “(..) a civilised, cultured Riga lady (..) on whom small hats, tailored outfits and silver fox wraps were so becoming.” In old photos of Zenta we see a demure Renaissance beauty, whose slightly introverted face exudes the golden light of a warm heart. The foundations for Logina’s professional life were established by her first authority, the master Romans Suta, with whom she studied painting at the Art Academy in the 1920s. This was in spite of the fact that her talents had been derided by no less a figure than Vilhelms Purvītis. Perhaps this just strengthened her resolve to prove herself. In the 1930s she worked as an assistant in Suta’s studio, and it is probably Suta who planted the seeds of modernist thinking in the young artist’s mind, which so unexpectedly and even paradoxically “burst” in her older years. There was still a long way to go to the awakening of the dormant “volcano” of Latvian modernism in the person of Logina. Searching for her place in art Other teachers also played a significant role in her artistic growth. In the 1930s Logina studied with Sergei Vinogradov, an outstanding painter and spiritual aristocrat who no longer wanted to return to Bolshevik-controlled Russia after visiting the West. Having fallen in love with Riga, he decided to stay there for life. He became a citizen of Latvia and a patriot who celebrated his new country in his paintings. He particularly loved the province of Latgale and spent a lot of time there, painting. It was in Latgale that Logina joined him for working sessions, and this may have deepened her bond with the region. In any case, at this time Logina met a more visually contrasting man, the somewhat bearish Latgalian publicist and economist Bonifācijs Logins, and the couple married in 1933. But fate awarded them only eight years together. | |

View of Zenta Logina's personal exhibition in St.Peter's Church. 1987 | |

| Logina’s artistic life can be divided into three periods: the two decades before and during the war ending in 1945, then the early Soviet “vegetation” or “condensation” period (1945–1963), and finally, the years of her retirement, when her personality blossomed and she brought modernism into Latvian abstractionism (1963–1983). In terms of form and technique also Logina worked on several levels. Initially she was a painter, this was her main profession. We are now more familiar with Logina’s period of fame, when she made abstract art, but her earlier works (from the 1930s to the 1950s) are also noteworthy, although she had yet to develop her own individual style. Today Logina’s early period could surprise us just like her abstractionism. Perhaps not with the same innovative revelations, but certainly as a fascinating overview of the styles employed by the Latvian masters of the 1930s. Initially, Logina was daring enough to do figural compositions. Her paintings clearly reveal an orientation towards lofty prototypes such as those found in the works of Augusts Annus, Jānis Tīdemanis, Valdemārs Tone, Leo Svemps, Eduards Kalniņš and other masters. Painter Džemma Skulme has made another interesting observation: “Zenta never lost her competitiveness and her desire to be better than male painters. And she managed to do this convincingly.” So at the fore – a competitive spirit. One can of course debate whether seeking to prove gender equality or superiority through art is a rational approach to creativity. But whatever the motivation, Logina’s efforts bore fruit. Her skill at working in seemingly different styles was surprising. Perhaps this drew the artist’s attention away from developing her own artistic individuality, but she more than made up for this “delay” with her work at the end of her life. The bitterness of an era Zenta Logina’s husband Bonifācijs was arrested in 1941 by the Soviet regime. Evidence suggests that the pretext for this was not political, but rather an economic crime for which he was made the scapegoat. This type of situation could arise under any other regime, with similarly severe repercussions. However, the barbarism of the “new era” was marked by brutality not only towards Bonifācijs, but also towards members of his family. Loved ones were taken away, deported, no contact was allowed and no news of them was given. The usual orders were: “...без права на переписку...” (without the right to correspondence)¹. Where did he go, what happened to him? Then the war. And seven years passed before Logina managed to coax out of Soviet bureaucrats the “secret” information that her husband had died somewhere in the depths of Siberia. We can imagine how these experiences may have prompted an urge to withdraw. However, the only concrete reference to political repressions relates to the Nazi occupation, about which Logina herself wrote: “In 1942, I was banned from exhibiting or selling my work for eight months because I was considered a politically suspect person. I continued to create and sell my works in secret. After the sanctions were lifted, I began exhibiting again and sold my works in an art salon.” Again, as if nothing serious had happened, but it seems strange – what was it in Logina’s neutral and benign persona that could have so worried the Nazi security services and parteigenosses? An fine upstanding Soviet Latvian artist It is important to recall here that, in addition to her painting, before the war Logina had acquired professional textile designer skills. In 1936 Zenta Logina travelled to the Third Reich to visit her sister Anna, who had married and was living in the town of Halle, and Zenta also spent several months studying textile design in Berlin. Thankfully, these dangerous facts (a sister in the worst of the West, studies under the “fascists”) in the later Stalinist period somehow went unnoticed by the security organs, or perhaps they only pretended not to see. Nevertheless, these were the foundations of Logina’s textile craft with which she earned her living throughout the Soviet period. This factor also probably played a dramatic role in Logina’s positioning on the Soviet Latvian artistic stage. Here it should be remembered that the USSR Union of Artists, whose dogmas of socialist realism became the norm in Latvia after 1945, was structured like a strict medieval guild. All work was organised into professional sections: for painters, sculptors, graphic artists and applied artists, including textile artists. The members of each section fiercely and jealously guarded their respective spheres, not infrequently motivated by material concerns, as well as fear of competition or professional snobbism. This meant that any attempts by members of one section to encroach on the turf of another section – for example, by trying to display paintings by textile designers at an exhibition for “real” painters – were rarely successful. The “intruders” would be looked down upon, accused of dilettantism and informed that they lacked the required qualifications etc. Despite all her personal trials, the enterprising Logina was able to play an energetic role in post-war artistic and social life. She, it seems, stoically assessed the situation, accepted the Soviet reality of the time as it was and without hesitation became a member of the Soviet Latvian Union of Artists in 1945, as a painter. She participated in exhibitions, including a major exhibition of Soviet Latvian art in “the capital of our Great Motherland” – Moscow. So at least outwardly in Logina’s work we cannot see any subversive intentions or efforts. She appears to have been a proper Soviet artist who painted mainly still lifes with flowers, and occasionally earned some money through textile projects. It should be noted that the hundreds of textile design drawings made in the 1950s are a significant and underappreciated aspect of Logina’s work, and are deserving of attention by the Museum of Decorative and Applied Art. They represent a fascinating cross-section of the style of the period and reflect masterful graphic design which is worthy of public interest, and at least an exhibition, a publication and a place in protected state collections. These seemingly humble “money-making” works are also important stars in Logina’s constellation. A certain dualism therefore emerged, wherein Logina was a painter who was recognised also in connection with textile art. According to some of her biographers, in 1950 Logina was expelled from the Latvian SSR Artists’ Union. Occasionally, hinting at the repressive Soviet system, it is remarked that Logina was punished for formalism and for trying to be creatively independent. However, there are some factual distortions here. Was Zenta Logina expelled from the Artists Union? As shown by the USSR Artists Union (AU) Presidium Organizing Committee Protocol No. 3, signed on 9 February, 1950, Logina Zenta Karlovna was never expelled from the Artists Union, but was only relegated to candidate status for a year with a completely opaque and quite nonideological motivation: “for insufficient creative activity and a decline in the level of creativity, which at present time is not up to the requirements which have been set for Latvian SSR AU comrades”. And she was given the opportunity to “raise her qualification to Latvian SSR AU comrade level” within a year. So it was merely dissatisfaction with an altogether respected comrade’s professional qualities. The most likely explanation for the whole action is that there must have been some sort of local intrigue of an internal nature, a “settling of accounts”. But in no way can we see any ideological repression by the Soviet regime here. Because landscape artist Konrāds Ubāns and the master of flowers Leo Svemps, for example, were just as neutral as still life artist Zenta Logina, and they were never affected by such problems. This makes us think about the universal human factor, which has operated at all times and across all eras. It’s worth recalling artist Rita Blumberga’s reminisces about Zenta Logina: “She was an independent observer, and at times it seemed that she was unable to “descend to the ground”. Zenta disliked monotony, and despite restrictions always tried to do whatever she wanted. This artist was able to maintain her intelligent stance during the Soviet period, she didn’t gossip and fraternise, and for this reason intrigues were woven against her and Z. Logina was denied a fully-fledged artistic life.” So was it due to other people plotting and scheming, rather than the regime? | |

View of Zenta Logina's personal exhibition in St.Peter's Church. 1987 | |

| It should be remembered that it was a highly controlled era and in the Stalin period, not long after the mass deportations, only someone wishing to commit suicide would think of starting something in their art which would diverge from the guidelines and norms set by the Party, knowing all the potential risks. Plus at that time, when the Iron Curtain was still hermetically closed, no-one had any real idea about what was happening in Western modern art. Even an “undue” interest in French classical cultural values which were fairly accessible, for example, led Kurts Fridrihsons and his confederates to the Gulag. What sort of modernism or formalism could there be? In Latvia it existed only in the memories and experiences of the pre-War generation. But this was a period when a furious war was waged on both “rootless cosmopolitans” (безродные космополиты) and “cringing before the West” (низкопоклонство перед западом). However, these processes in their essence developed against a poorly disguised background of anti-Semitism, and Zenta Logina couldn’t in any way be included into this category. Specific persecution of “formalists” only intensified with renewed vigour about twelve years later – in 1963, during the Khrushchev period. That’s when Zenta Logina was pensioned. Yet we cannot find any signs of this “cardinal sin” – formalism – in her entirely correct realistic art of the 1940s–1950s. Moreover, even as an AU candidate Zenta Logina continued to participate in painting exhibitions right up to 1952. There were no prohibitions on the artist exhibiting, as, in accordance with the conditions placed on her, she continued to raise her qualifications in this way. But in April 1953, one and a half months after the death of “the father and teacher of all nations”, news arrived from Moscow that in accordance with the USSR AU Presidium Organizing Committee meeting decision and Protocol No. 13, the USSR AU Board’s decision was confirmed and “уважаемий товарищ Логина Зента” (‘the honourable comrade Logina Zenta’)² had been restored the status of being a fully-fledged AU comrade, albeit now in the Applied Arts Section. It should be added that this too can’t be interpreted quite like a “being put in one’s place”. Zenta Logina’s own draft submission addressed to the Artists Union, where her request to be accepted specifically in the Applied Arts Section is expressed, has been preserved. It’s not really clear, however, just how voluntary this change in professional orientation or emphasis from painting to the textile arts was. Even as a textile artist, Logina continued to paint flowers, but this part of her creative work disappeared from the public eye until the end of her life. Evaluating the situation realistically, textile art may have been the more lucrative. And in the 1950s Zenta Logina became heavily involved with textile production plants, mainly in the ‘Māksla’ group of enterprises. The sources of Zenta Logina’s “formalism” The year 1956 marked the onset of the Khrushchev “spring”, which began with a process of de-Stalinization. This period was characterized by a palpable ideological liberalization, and as a result, some wider gaps appeared in the Iron Curtain as well. In the field of culture unprecedented opportunities developed for foreign links and the exchange of ideas. Alongside legalized opportunities for contacts with foreigners, Western films, exhibitions, literature and concerts etc., began to make their appearance in the Soviet Union. Not only were there art books, but one could also order foreign, in the first place socialist nation, art periodicals. All this also paved the way for the flourishing of Western modernism in art. The change turned out to be so radical that it struck fear in Kremlin leadership circles, as threats of “ideological counter-revolution” began to loom before them. In late 1962, the famous anniversary exhibition by the local Artists Union Painting Section took place in the Manege in Moscow, with the participation of a wide range of Russian modernists. The USSR First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev, uneducated in the humanities, having arrived there displayed stormy disapproval and called the modernists homosexuals. However, he did get into a legendary discussion with sculptor “formalist” Ernst Neizvestny, who later was to be the author of the party leader’s tombstone. The exchange of ideas did not lead to any positive outcome. Khrushchev maintained his view, which was also the view of his confederates– a “villainous” betrayal of socialist principles was taking place. In 1963, a massive, long-lasting and unusually grotesque Soviet Union-wide campaign began against “formalist and abstractionist” artists. The Party insisted that painting, sculpture and graphic art, just like literature, cinema and theatre was above all an ideological field and that the methods of socialist realism had to be closely adhered to. Though it wasn’t clear what to do with the number of “formalists” who had multiplied greatly, and who now couldn’t be repressed as radically as in Stalin’s time, which had now been condemned. A “Solomon-like solution” was found – to declare all applied arts, design and architecture as being outside ideology and to leave the “formalists” this enclosure of free art. This split the modernists into two camps and those who disagreed with this Communist Party position were forced “underground”. This gave rise to the Soviet non-conformists, who operated mainly only in the large cultural centres of Russia – Moscow and Leningrad. However, in the Near Baltic, local powerbrokers did not in any way want to ruin the “positive indicators” of their republics in Moscow’s eyes, and to mess around with any sort of “underground”. That would have meant cutting off the branch on which they themselves were sitting, and that is why the majority of the potential “underground” was integrated in various respectable and legal ways, levels and institutions. But those who repented their “sins” or agreed to “channel” themselves into design and applied arts even reached the status of Soviet cultural hero. It was paradoxical and comical, but the whole problem reduced down to simply the way the art work was technically executed, not its visual essence. Nearly everything that the “formalists” could afford to come up with in their designs was completely taboo if it was executed in oils. In the 1960s –70s, Elīze Atāre wove 65 wall hangings based on her sister’s – Zenta Logina’s “formalistic” sketches. In this sense, the artist wasn’t any sort of dissident, not for a moment, but had the status of being a completely legitimate Soviet hero of art. Though with a time bomb in her pocket, as Logina’s abstract paintings were going to remain only for displaying in “their own corner” for a long time yet. Was Zenta Logina a dissident? In the case of Zenta Logina, what was taking place in Soviet culture turned out to be a very beneficial catalyst. In 1963 the artist retired. As we can see from the ever-present piles of art magazines in her apartment, the new opportunities to obtain information and find out about art trends in the West from the very popular magazines of the time such as the Polish Projekt, the Czech Tvar, Vitvarni Umeni, or Western modern art books as well, were fully utilized. And her own abstract compositions appeared not as the result of some kind of dissenting attitude, but synchronously and exactly at the time when it became possible to do so under Soviet conditions, just like mushrooms begin to grow when it’s sufficiently warm and wet. The important thing is that Zenta Logina appreciated it all quite early on and knew how to make use of it productively. Against this background, the logical decision to “become legal” and to create her intended abstract compositions as projects for her sister Elīze’s woven mats followed later. So – officially completely laudable conduct in the field of applied arts and design. The successful presentation by the sisters of textile works at many exhibitions is yet more evidence of this. Towards the end of the 1960s, perhaps to strengthen her artistic position and so that no-one could incriminate her with introducing covert abstractionism or ideological diversion, Logina chose another no less justified argument – the theme of outer space. The “realism” of the Universe as if excused the free and “anarchistic” forms. It should be firmly stated, however, that cool calculation was not involved, as the outer space was another of Logina’s enthusiasms. This area of science attracted the artist’s deepest interest. A lucky coincidence, as in the 1960s space was the most topical and heroic of themes in Soviet society, the substance of social obsession, symbol of the era, a fetish. Communist Party ideologues held up the achievements in space as the greatest confirmation of the might of the Soviet system, where “our guys” had all of the advantages. And it was splendid if a Soviet artist joined in with this strengthening of the Party’s position. Many “formalists” adopted this sort of method – as if appealing to the roots of the abstract form in the realism of nature, to confound potential opponents, or even to scientifically substantiate their aesthetic position in a socially significant way. In Ojārs Ābols’ 1970s semi- abstract paintings we find realistically presented allusions to ecological themes, or, for example, the 1960s geometric abstractionist Leo Preiss, who based all of his artistic work on the exploration of crystals and minerals and scientific references. And for them, the same as for Zenta – it was not just a question of tactics, but a calling of deeply intellectual and social interest. You could say that the method of searching for analogies for abstract works in the natural environment is the same as predicting the future in coffee grounds or observing battles in the sky with cloud formations. One could impugn this method, looking at it from the aspect of purity of principle. But in the final run, the value of an artwork is determined not so much by the tactics or method of its creation, as the objective artistic result. Zenta Logina’s abstractions of the 1960s–1980s were partly motivated as innocent projects for further development in textile art. It was important that the artistic idea was realized in some sort of possible and authority approved material. We can find similar examples with many of the masters of the Latvian applied arts of the time. And it wouldn’t be correct to maintain that she was banned from participating in exhibitions. Such restrictions can only be applied to Logina’s abstract paintings, which in truth were among the regime’s eccentricities, although at marginal levels even at that time it was possible to exhibit abstract works as well. The painter’s reawakening Logina’s approach to the making of these textile projects is a completely different matter. Here it was as if a deep painter’s instinct had awoken in her. The “projects” have a distinct autonomous quality of a painted work and value in themselves. Without a doubt, she knew this very well. At least until the mid 1970s this type of art in the form of a painting was a work for one’s own private collection. Similarly, Ojārs Ābols’ radically abstract paintings painted at the beginning of the 1960s didn’t appear in public at that time either. With rare exceptions, for the art of the “formalists” public life was forbidden. For example, Kurts Fridrihsons’ abstractions on the walls of the Mežaparks Tennis Club were painted over. The ideological passions stirred up in 1963 around the “donkey tail dauber” abstractionists still hadn’t cooled. But within the artistic environment, the snowman of socialist realism dogma was melting rapidly and its demise was already inevitable. In the second half of the 1970s, the concept of socialist realism basically disappeared from public consciousness and the media space. It was only mentioned once in a while by some Communist Party functionary in a speech. And even then they had to refer to the various expressions of renascent modernism somewhat desperately as “developments in socialist realism”. Thus Zenta Logina’s works, in small doses, potentially could already appear in the public realm at this time, though perhaps not in “A class” arenas. | |

Zenta Logina. 1930s Courtesy of Fonds "Zentas Loginas muzejs" | |

| As demonstrated by Zenta Logina’s correspondence with the AU administration, in this particular respect – consistent with the stubbornness of her character – the artist turned out to be quite “fussy”. In 1970, the Art Foundation offered the artist a chance to organize a solo exhibition in the Science Building (now the Orthodox Cathedral) exhibition hall. But Logina considered it to be unsuitable and asked for the exhibition hall of the Artists’ House. The AU Board, however, refused this request and suggested that the exhibition be held at Rīga Castle. Logina was a woman of character and firmness – she wasn’t given to compromise. Evidently stubbornness and an adherence to principles took the upper hand, and so in her lifetime Zenta Logina never got her solo exhibition. Even though otherwise the textile works by the creative tandem of two sisters were purchased and also prolifically exhibited in applied arts exhibitions, both in the land of her birth as well as in other countries. Eruption In the mid 1980s, as a result of Gorby’s perestroika and the lifting of censorship, the art of the USSR, too, was freed from formal and ideological restrictions. Finally, the positive public unveiling of Zenta Logina’s unknown abstract paintings and creations also became possible, without any special tactical pretexts that they would be only projects for textile works. In 1987, Logina’s first major and officially approved solo exhibition took place at St. Peter’s Church. Even a “master of ceremonies” – one of the USSR’s celebrities, Soyuz 23 mission astronaut Vyacheslav Zudov, arrived for the opening of the exhibition in support of the overall theme of the works. The comprehensive exposition acknowledged the triumph of a great and powerful artistic personality, unfortunately this happened a mere three years after the painter’s death. There was enormous enthusiasm from the public, as yet unspoilt by more radical art. The exhibition was visited by about 40 thousand viewers. But differing opinions still circled around Logina’s abstract artistic works. Along with delight elicited by the sweetness of Soviet “forbidden fruit”, “guild prejudices” also, it would seem, played their role. Others even saw “some kind of textile person’s” pretentious and “unprofessional” interference in Latvia’s field of “pure painting”. And even false kitsch frivolousness... The gilded effects, the “crystals”... Just like those theatre or cinema set designers. Zenta Logina’s fame as a leading light of Latvian abstractionism really only cemented itself after the restoration of Latvia’s independence. This is when a range of exhibitions once again took place in her memory, including at the formerly so coveted gallery of the Artists Union (1996), when her works found their place in prominent collections in Latvia and other countries, and when this outstanding period of her artistic activity also received due consideration by art historians, and even international recognition. Yet in some contemporary evaluations, Zenta Logina’s greatness at times seems to be as if not enough. Then come the attempts to dramatize, to make her a hero, assigning her the aura of a martyr of the regime... And all too often the desired is given as fact without concrete corroboration. In all of Logina’s Soviet period we cannot find a substantially respectable and direct fact of repression. Even with regard to an invitation to come for a “chat” at the “house on the corner” [the KGB Headquarters in Riga], Zenta coquettishly observes in a note to her sister that the Cheka must be interested in the AU “congress goings-on”. In examining Zenta Logina’s life and work, we can see that she’s been a victim or been oppressed no more than the majority of our artists. All of them equally clearly saw and felt the depressive nature of the regime. But for most it didn’t interfere with their productive activity, often enough through the use of tactical deceptions. Can we say that the officially well-situated Academy of Art Professor Boriss Bērziņš or Jānis Pauļuks, or Rūdolfs Pinnis, or Biruta Delle and very many others were artists engaged by the ruling power... All were in their own way “encrusted” in the system, but still maintained their complete autonomy in art. Just like the “Soviet artist” Zenta Logina, who actively worked in the Māksla enterprise and other profitable institutions. It seems that her greatness in painting today is convincing enough and her contribution to Latvia’s art sufficiently significant for there to be no need magnify it through various decorative “improvements” and ideologically motivated fabrications. Thanks are due to Pēteris Ērglis, an activist from the Foundation Zentas Loginas muzejs, for his collaboration in the preparation of this material. /Translators into English: Filips Birzulis and Uldis Brūns/ | |

| go back | |