|

|

| Taking a different direction... Jānis Borgs, Art Critic Scraps of recollections after the exhibition AND OTHERS – Directions, Movements and Artists in Latvia, 1960–1984 | |

| It has finally happened. The Age of Pensioned Heroes has begun, when you start getting invited to impart to children, loftily, how “it was all different when we were young...” The exhibition AND OTHERS.., magnificently assembled by the Centre for Contemporary Art, brings up sentimental recollections of youth, a time when we didn’t have the slightest idea, and, lamentably, not even the slightest intention of accomplishing anything historically significant. In contrast to other exhibition viewings, this time it tugs at the heart-strings, because now I’m an “insider” – one of them, the participating artists whose work other observers can evaluate. Even though my American colleague Mark Allen Svede, for example, who became active in the search for ‘other directions’ much earlier, has managed to skim off the cream of such ‘alternative’ artefacts, which in some cases had already been thrown out as rubbish (which means that nowadays they lie in collections over the ocean). Albeit a very belated home effort, the exhibition in the Riga Art Space gladdens the heart like a lifeboat finally calling at Robinson Crusoe’s island. The exhibition succeeds like a proper broth, where the true essence has been extracted. Perhaps not quite everything gets said, but it’s enough to give a real sense of satiety and a somewhat surprising revelation of the yearnings and strivings of a long-gone age. It is an event where the curators have done an impressive job, and the presentation of the exhibition is wonderfully designed. One of the surprises could be the revelation that such diverse modernism and seeming controversy was able to exist and even flourish in an age of totalitarianism and in a milieu where, as people are nowadays led to believe, ‘no grass grew and not a bird twittered’. My ‘comrade in arms’ since sandpit days, artist Juris Dimiters, who has also actively walked ‘other paths’, ironized in his own characteristic way at the opening of the exhibition that it could all be presented in an even more tragic light, namely that “in spite of the persecution and torture chambers, with shirts soaked in blood and in the darkest night we did not give in and fought to the end...” Perhaps we might even earn ourselves some extra recognition this way, some bonuses or concessions...? The many artists who took ‘other directions’ definitely each had their own particular history, their own background, their own sources and ‘secret linings’... I, too, am stimulated by the exhibition to try to fish up from the pool of memories the morsels of my beginnings in art. At the start of the period in question, in 1960, the very deepest Sovietness prevailed, Egypt-like in its indestructibility. At the time when this ‘other direction’ was commencing I was only 14. I had barely dipped a foot into the enticing flow of art. In truth, it was an entirely unforeseen coincidence that I even came near it. In my childish mind I had envisaged myself in the future as an explorer of the world, and accordingly engaged in romantic visions of the professions of aviator or geologist. Whereas art had associations with various illustrative messages – Shishkin’s bears and suchlike. In my early years, going to church with my grandma, I had to sit out tedious and incomprehensible services. To pass the time, I’d examine the pictures on the white walls, with scenes such as the ‘firemen’ (later I learned that they were Romans) tormenting a naked, bony man in all sorts of ways. Probably this evil-doer truly had deserved his suffering... As opposed to attending church, I was always longing for my Mama to take me out for cakes at the Milk Restaurant café (the present location of Radisson Blu Hotel Latvia). There on the wall, in the place of honour, was an enormous copy of the painting The Ninth Wave by Aivazovsky, with the dramatic scene of a drowning man clinging desperately to a fragment of the mast, a depiction that that in no way diminished my equally realistic enjoyment of the tasty treat. The magic of art was expressed in frightening and mysterious tales... | |

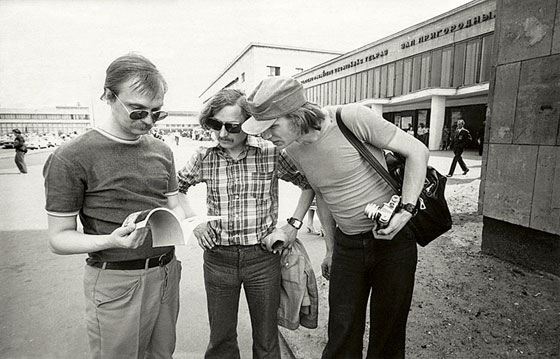

Pollutionists' group. Jānis Borgs, Valdis Celms and Māris Ārgalis. The first half of of the 1980s. From Jānis Borgs' personal archive | |

| I was awakened from peredvizhnik slumber by the young artist Džemma Skulme. In about 1956 she spotted a blonde little boy in the choir of Mežaparks Primary School who, [she thought], would be just right as a model for the illustrations of some literary classics. Thus, I was transformed into Oliver Twist. For my present associates, in whose eyes I’ve long been ‘Mr Hundredweight’, such a metamorphosis may be rather difficult to imagine. But it only goes to show that everything in life is subject to inevitable change. Even more interesting was Skulme’s husband Ojārs Ābols, a ‘really cool guy’, a Brad Pitt kind of painter, who came to school and, sitting on the desk in Yankee fashion, started telling the children all sorts of strange things about what art really is. Judging from the rather alarmed faces of the teachers, I perceived that he was telling us something entirely ‘wrong’, and that there were hitherto unknown horizons of values opening up, some kind of emergency escape route from the chamber of regimented dogma... Because, on the contrary our drawing teacher, for example, whose core competency was actually physical education, never ceased to warn us of ‘idiots and daubers’ like Purvītis and Rozentāls. Now I learned that it was all about this most refined French thing called Impressionism, and that not only the Russians had good art. Gradually, praise for the Impressionists – this century-old moss-covered Western ‘innovation’ – came into fashion during the ‘Thaw’, and in Soviet society it came to mean being in tune with progressive ideas. Albums of reproductions of works by Van Gogh, Lautrec, Matisse and Gauguin (which some used to pronounce ‘gowgoowin’) even appeared in the shops. Meanwhile, in the school toilets, boys would crowd around an illicitly imported ‘wonder’ – a transparent ball-point pen with a beauty depicted inside it, whose dress would fall off when you turned it, revealing naughty bits. Once things like this had been sufficiently relished, we started pondering on slightly more intellectual novelties from the West: “...guys, have you heard what those crazy Ameri-cans are doing? Now they’re treating any kind of monkey-doodlings as serious art!” Who cared about the Impressionists now... And thus I inadvertently learned of the existence of abstract art. I was fortunate, because I had someone I could ask whether the story about the monkeys was true. Ojārs Ābols, my first authority on the arts, promptly and thoroughly gave me a clear ‘Darwinian’ account of the human origin of this phenomenon and opened my eyes to the immense global diversity of ‘-isms’. At the same time, he drew attention to the rich heritage of modernist art from ‘bourgeois Latvia’ which was kept hidden from most of our society. Some of this could be admired tête-à-tête in the form of outstanding original works held in the private collection of the Skulme family. In my search for answers, I eagerly delved into their well-stocked library, where the most profound source of revelations turned out to be Knaur’s Lexicon of Modern Art. With the help of a dictionary and my new guru, I squeezed this and other publications dry like lemons, so that I now had a new aim in life – to become involved in the world of art and to be an apologist for mod-ernism. Needless to say, this was very élite knowledge, alienated from the surrounding milieu of that time. Having been for a time the somewhat delicate ‘Oliver’ among my more athletic schoolmates, I could now even quite cheekily enjoy my ‘special status’. The real departure for ‘taking a different direction’ began at the School of Applied Arts. Initially, I was quite alone in my exploration of modernism, because it was clear that my fellow students had not grazed on such rich pastures of information as I had. From lessons in the history of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, I was aware that the time was not yet ripe for me to establish a party of my own, and that, before ‘capturing the post office, telegraph and bridges’, it was of decisive importance to carry out propaganda work. To put it in Leninist terms – a spark was needed to ignite the fire... This developed into a lasting habit of sharing and propagating among my peers large quantities of any information that was available about modernist culture. Because of the sheer ‘tonnage’ of publications on this theme, bringing them to school became my main physical culture. The number of like-minded individuals also increased. My first and closest fellow-thinkers, apart from Juris Dimiters, were fellow classmates Henrihs Vorkals and Atis Ieviņš. In the same year as me, but studying fashion design, was the later famous king of Latvian hippydom, Andris Grīn-bergs. I first met him in the course of some practical work, when, together with Atis Ieviņš, we were painting the boys’ toilet at school. For some reason Andris had been sent to assist us. Little by little, at various get-togethers, a whole band of ‘young and promising’ individuals emerged, each of them a talent charged with passion, glowing with bright creativity and at odds with official culture in one way or another. Going in a different direction inevitably meant thinking differently... At the bottom of it was a total, and occasionally quite naive and idealized, belief in Western culture and orientation towards it, something that was still regarded as highly undesirable. In terms of artistic activities it often developed into a superficial imitation of very indirectly received (like a third infusion of tea) influences from Western art, lacking any structural foundation or coherence. In 1963, throughout the USSR there began a massive and protracted anti-modernist campaign. Looking back at it now, it was a truly tragicomic orgy of obscurantism. Apparently Jekaterina Furceva, the Minister of Culture of the USSR of that time, once threateningly joked to critics from intellectual circles who had ironized about her incompetence on issues of modernism: “An Abstractionist passes by. But he’s being followed by two Realists. Both in plainclothes.” The persecutions by the authorities were not nearly as dramatic as during the time of ‘Joseph the Terrible’, or Comrade Stalin. The reaction was more like a hysterical tantrum thrown by a cranky child. The modernist artists, or ‘formalists’, as they were labelled, had to reckon with harassment, loss of employment or study opportunities, a ban on publication or even a semi-criminal accusation of tunejadstva1 (and back then I didn’t yet comprehend the link with ‘tuna eating’)... At the very height of the ‘reaction’, in my profound naïvety I made a very risky move and decided to ‘go on the warpath’ in my own way. I would apply the knowledge I’d accumulated concerning American abstract art, which truly captivated me at the time (I was an ardent Mark Rothko fan), in a most subversive way by creating the decorations for a ball at the School of Applied Arts. And at the same time I’d be under-taking ‘educational work among my revolutionary comrades’. Imitations of works by Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell and other ‘donkey-tail daubers’ (as the abstractionists were labelled in those days in official propaganda) were ‘painted’ on large sheets of wrapping paper. Our teachers, unaware of the potential for ‘ideological diversion’, didn’t interfere in any way. Hoping for greater effect, I also held a competition to identify the artists. Of course, it all flopped, because nobody saw the slightest resemblance to any kind of art. I was, as they say, ‘too alienated from the masses’. Strangely enough, the only one who really appreciated what was going on was our drawing teacher Vitaly Karkunov, an outstanding exponent of the Russian Chistyakov method of drawing, whom, on account of his academism, I regarded, most unjustly, as ‘black-hundredist and reactionary’. Somewhat sadly he scolded us, creators of the decorations: “Those men in America are doing all that with the blood of their hearts, but you, laddies, are just horsing about.” He was an honourable man: although wise to our game, he didn’t report on us to anyone, so this time I was spared the hypothetical ‘hot water’ and the almost guaranteed scandal with unfore-seeable consequences. | |

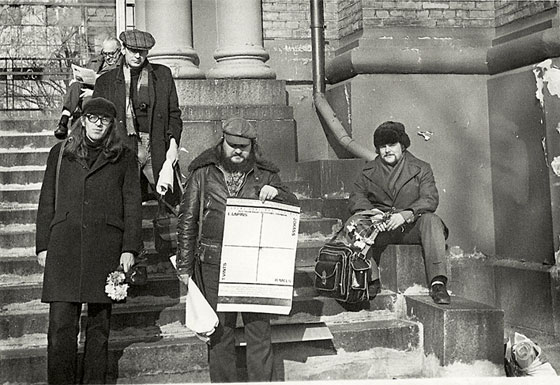

The exhibition of Tonis Vint, Juri Okas, Leonhard Lapin and Raul Meel in Riga, the exhibition hall of the House of Knowledge. Leonhard Lapin with the poster of the exhibition designed by Jānis Borgs. 1979. From Jānis Borgs' personal archive | |

| Strangely enough, amid the ideological storm raging around us, the School of Applied Arts turned out to be a real greenhouse or oasis, where truly national culture was cultivated (this is under conditions where the “native” party had firmly vowed to develop a completely new type of Soviet person in distinctly Russian form). Moreover, the school adhered closely to modernist design principles. My second great mentor and guide in life and the arts, the headmaster Imants Žūriņš, passionately opposed academism and propounded modernist ideas. In addition to the masters of the Riga Group of Artists, such as Valdemārs Tone, Romāns Suta and Jēkabs Kazaks, he presented the major French Cubists as the benchmarks in painting. And, as first and foremost – Georges Braque. Pride of place in his small, select library was held by the SKIRA publications on the Cubists and other classics of the avant-garde, which in those days could be hunted down in second-hand bookshops. Later on, in the second half of the 1960s and the 70s, when I became composition teacher at the school, I included in the curriculum exercises in copying the modernists. The exhibitions of work created in composition classes by pupils at this Soviet art school were full of Mondrians, Braques, Picassos, Maleviches, Lissitzkys and Klucises... Nowadays I can only wonder what the all-seeing surveillance ‘organs’ were doing back then. There isn’t the slightest doubt that they were receiving a constant stream of unfavourable ‘signals’. Nevertheless, although thunder rumbled at the horizon, lightning never struck... Presumably, Big Brother at the ‘House on the Corner’2 was more concerned with combating overt (or imagined) political opposition, leaving purely ideological problems, especially those relating to modern art, mainly to the ideologues of the Central Committee. After all, this was such a murky field, so difficult to define, that few plucked up the courage to delve into it. Apart from this, the sheer ignorance of modernist culture among the people in power made it possible to slip many things past them. An odd kind of ideological ‘scholasticism’ developed, an attempt to coexist more or less amicably with modernism by jus-tifying it as ‘design’. In fact, even the official orchestrators of art did not wish for ‘Socialist Realism’ and ‘real Soviet art’ to smell like moth balls. Here, too, a special kind of modernisation was underway, the language of form retreating considerably from the naturalistic. And nobody was really sure any longer where the boundaries lay. Moscow even tended to take a pride in the harshly modern forms of realism in the Baltic. The aforementioned Comrade Furceva expressed her satisfaction, af-firming that the art of the Pribaltika represented ‘our own West’... In the Baltic especially, modernism had, in multiple ways, become intertwined with officially sanctioned culture. Thus, for example, in the first half of the seventies, together with painter Jānis Krievs and in collaboration with the Māksla company, I managed to implement an enormous supergraphics project at the Saules kalns tourist centre, which has nowadays been turned into a pile of ruins. It was in this same system, in a project led by architect Māris Gundars, that I designed an ambitious minimalist-geometric sculptural object, which was accepted with acclaim, however was not implemented solely for lack of finance. Particularly in the 70s, the term ‘design’ became the main protective shield behind which the modernists could conceal just about anything. However, ‘experimental’ work could be seen in the public sphere even without this kind of mask. I remember a rather comic episode already in the 70s, during my few years as headmaster of the J. Rozentāls Riga School of Art, when I was invited to take part in an exhibition of work by the teaching staff. I contributed an entirely incongruous work – three sheets of technical drawings, consisting of arrangements of black lines. This was ‘programmed art’, where the will of the artist has no role. It had been created entirely by means of a programme, using the principle of complete randomness to determine the composition of the elements. The works were intended to be created by computer, but in those days there was no technical equipment of this kind available, and so everything had to be done by hand. In other words – imitation computer art. From the traditional perspective of art, it was absolute nonsense. But I’d decided on a shameless display of conceptualism, which was so important to me at the time, and because of which I’d already established extensive international connections with like-minded people. It seems that my traditionalist colleagues, who had no experience in this field, deliberately hung them the wrong way up, or so they thought. The joke flopped, because in this case the arrangement had no significance, and I kept a straight face. I was evidently in the wrong place, and perhaps this was applicable in general to my time as headmaster. It was a strangely ‘avant-garde’ move by the Ministry of Culture to appoint me to this post [in the first place], because I was well known to be an ‘extremist’ in art, someone who wouldn’t fit into academic education in any way. It seems that the ministry began to sense this contradiction even more acutely when I caused it problems by participating most conspicuously in a concert happening by Alexey Lubimov, something that diligent informers interpreted as a ‘hooligan outburst’. It was certainly not such a depressing period as it’s sometimes made out to be, and creative life was full of enthusiastic activity that could in no way be deemed underground, since it was all going on in quite official circles and levels. For me the time of other directions was saturated with all kinds of activities within the sphere of my ideals. For some time, while working in my studio, I participated in the bohemian atmosphere of the ‘Mežaparks Commune’. From my study years I remember as kindred spirits my fellow student Leo Preiss, who painted in the spirit of Geometric Abstractionism, as well as Leonīds Mauriņš, Pāvels Tjurins, Romualds Geikins... And the master Bruno Vasiļevskis, who had emerged from the ‘French Group’ and positioned himself as an ‘Unmodernist’. The spirituality of his fundamental realism was enthralling, and in our long night-time talks I perceived him as an outstanding kindred soul. Ilmārs Blumbergs was perhaps the greatest and most profound philosopher among our artists... In any case, the list of like-minded artists could be continued for many more lines. In the course of only about a decade, the sense of absolute solitude was replaced with the bustling activity of people like myself. The restrictions on information and the drastically curtailed possibilities of foreign travel led to a heightened sense of taste, appetite and enjoyment, something that we’ve completely forgotten now, as we bathe in an ocean of information. My circle enjoyed intensive collabor-ation with the Estonian and Moscow avant-garde (Tõnis Vint, Leonhard Lapin, Raul Meel, Matti Milius, Francisco Infante, Viacheslav Koleichuk, Ilya Kabakov...). And then the mighty Westerners appeared: Valdis Ābo-liņš, Indulis Bilzēns... The time of ‘other directions’ concluded for me with taking part in Māris Ārgalis’ active group of ‘Pollutionists’. That, however, came to a close with a paranoid and Kafkesque conflict in the style of shadow theatre and behind-the-scenes struggles with the institutions of authority: the Central Committee and the KGB. Without any clearly defined reason, we earned ourselves a year-long ban on public showing of our work. In my view, all of the ‘other directions’ came together in the major exhibition of 1984 Nature. Environment. Man. Very soon after this there followed ‘a different Soviet period’, when the art avant-garde acquired the status of undisguised legality and even tangible support from the authorities. It’s not as if I could complain that life has been unfulfilled. Yet I cannot in any way understand those individuals full of bravado who proudly declare that they regret nothing in their past. I bitterly regret every wasted minute, because providence had unfortunately stunted my thinking, so that I was unaware we were doing more than just living our lives – we were continually creating history. /Translator into English: Valdis Bērziņš/ 1 A pun on the Russian words tunec (tuna) and tunejadsva (idler). 2 The headquarters of the KGB in Riga. | |

| go back | |