|

|

| Jānis Taurens and Līga Marcinkeviča's conversation on July 9th | |

| Līga Marcinkeviča: August and September will be your time in the spotlight. I wonder how the stars are aligned in your horoscope for this period (joke). On August 15th, the Aspen–Kemmern exhibition, for which you and Zane Onckule are the curators, will open at the kim? Contemporary Art Centre; the Survival Kit 6 Festival, where you and Reinis Dzudzilo are participating as artists, will begin on September 4th; but the most significant event, in my opinion, takes place in mid-August, namely, your book Conceptualism in Latvia / Preconditions for Thinking (On the day of our conversation, the date of the opening for the book was, as yet, unknown, but it is thought that it could be linked to the opening of the exhibition at kim?). Jānis Taurens: Or the complete opposite – a fiasco. L.M.: The witnessing of three expressions of your thoughts will be possible almost simultaneously: you – the curator, you – the artist, you – the writer. J.T.: There will also be a fourth: me – as a critic. (We both have a laugh here, to my mind, because we understand that the coming period will be very complex for Jānis. On September 18th, the Artishok Biennale will also open at Mūkusala Art Salon.) Šelda puķīte has invited me to take part in an event called the Artishok biennale. As she has an interest in the status of critique, she has also invited writers who are not really critics, for example, pauls bankovskis and me, to take part. there will be ten artists – five from estonia and five from latvia – and ten critics. the origin of the concept can be found in estonia. And each critic will write about each work of art. Yes, but there’s also a fifth – family life. reinis dzudzilo provided me with the stimulus to make this note. we had to write short biographies for the Survival Kit project, and he wrote that he lives with his wife. And then i understood that that’s also a good way of telling about yourself. it’s an important fact in a biography, because what you studied is often just sort of a matter of chance; the main things – what you read, reflect on and write about – you do yourself. L.M.: Something like self-development? J.T.: Well not quite. but a person has to know how to do three things: speak, read and write. And all of them are very difficult. i admire those who can write in a number of languages – nabokov and beckett. Speaking is also difficult. And it’s difficult to find a real way of expressing yourself that satisfies. reading – exactly the same. reading should be a significant part of life. it’s the only way of not living in an illusory way and of making contact with reality. (that’s a paradox, isn’t it?) we also only access the past through texts. the impact of text is different than that of the image. texts are more powerful, because one and the same text – even the most detailed description – can be visualised in different ways. text engages a person’s fantasy and imagination. yes, these are the three things for which no formal education can really provide assistance. L.M.: Discipline is required. J.T.: passion. if there’s passion, then the time can be found and all the rest. | |

Jānis Taurens. 2014 Photo from the private archive of Jānis Taurens | |

| L.M.: Please tell us about the work of art that will be on show at the Survival Kit 6 festival. J.T.: The work of art.... the idea came about jointly with reinis, when we looked at the space where it would be exhibited. there were a lot of ideas – utopia is much too broad a theme – and also a lot of material. reinis said that we’d look for a visual solution when the event site for the exhibition had been clarified. the conceptual base for the work also derives from that. in the vāgnera Street building, which formerly housed wagner concert hall, we found a mezzanine space with a very low ceiling that immediately reminded me of the low ceilings in kafka’s novels and stories. benjamin writes about them in his texts on kafka. in his interpretations of kafka, the central character for benjamin is a sort of hunchback, whom he finds in fragments of kafka’s writing to which we often don’t pay much attention. for example, in The Trial the galleries of the court hall have such low ceilings that visitors take little pillows with them to support their heads. And in one portrait, the chin is bent down so low that it has grown into the chest. Absurd descriptions like these, which benjamin calls “gestures”, in trying to construct an interpretation of kafka. if we talk about cinematographic adaptations of kafka’s works, then orson welles 1960s adaptation of The Trial was played out very successfully. the action in the film begins, it seems, in some district of zagreb (if i’m not mistaken) built in the 1950s. in the opening scene, there is a space with a very low ceiling – just above the door jamb – where the main hero, josef k., awakens. When i entered the space on vāgnera Street, i immediately felt similar associations. there was also a fireplace, repainted and lacquered in a pink colour. See, that’s where the idea came about as well, that the concept of utopia could be connected with the mood of a surreal dream (in the initial idea there were to be four fireplaces). the next step was that all of the texts forming the work of art would be in four languages. if they were played simultaneously, it would initially create an undistinguishable babble of voices, but, on approaching the source of one or another sound, one could, of course, distinguish a single text. And the unintentional congruence with one of roland barthes’ ideas was only revealed later. barthes had a short article, belonging to the post-structuralist period already and, if i’m not mistaken, written in the 1970s, called Le Bruissement de la Langue, which i translated as ‘the droning of tongues’. in it, he plays with the droning of motors, which he calls a language utopia: language in this condition is freed from its direct functions; the point doesn’t disappear, but it sort of remains in the background. correspondingly, there’d be a babble of languages in the middle of the space in our work – a language utopia – with the point being in the corners of the space. It’s possible that what we’re hoping for may, as usual, not come to pass due to financial difficulties. but the important thing is the concept for the work (and the way of making it happen is interwoven into it), at the core of which are the summaries of four fragments of text, four female voices. Aristotle’s text about the first urban planner, hippodamus, who planned Athens’ port city of piraeus, would be heard in the language of the Ancient greeks. Aristotle recites his ideas about the ideal nation and national system. we can’t really tackle plato’s utopian plan for the ideal nation, because this requires a serious and broad interpretation, and that’s why i chose plato’s Crito, which has references to Atlantis. well, even if we don’t understand the greek language, the name Atlantis will be recognisable. A text in the english language will be the continuation; it will be made up of fragments from francis bacon’s unfinished work New Atlantis, which reveals his utopian ideas and the role of science in them. And then a small fragment from h. g. wells’ 1905 work, A Modern Utopia, in which the image of the state as a ship is important. interspersed would be a little poetry: edward lear’s Limericks, because, in the end, the idea of a utopia also has a touch of absurd nonsense about it, and the poems of the 19th century english poet ernest dowson. we’ll hear fragments from walter benjamin’s unfinished The Arcades Project, and a little from Traumkitsch (dream kitsch), which he wrote in german in the 1920s, when he was introduced to surrealism. in it he expresses an interesting thought, namely, that dreaming and the dream no longer open up new horizons for us today, that the dream is no longer, as we’d say, a “pale lads” episode; the dream becomes grey and transforms into the banal. this dovetails well with the dream atmosphere that could be created in the space at wagner concert hall and also with the quite banal colour of the fireplace. we don’t, of course, have any significant text about utopia in the latvian language. only the utopia of the relationship between benjamin and Asja (real name Anna lācis). benjamin and Asja met on the island of capri in 1924 and soon afterwards a small work called Naples was created. it was published in the Frankfurter Zeitung newspaper in 1925, is found among the writings of benjamin, and Asja quotes a few “passages” in her memoirs. the text, which we asked Asja’s granddaughter māra Ķimele to record, is a fragment from Naples and will be in latvian. L.M.: Listening to your story about the work of art that is yet to be created, I understand – at least I think I understand – the idea behind how you are going to create it. You are basing it on language, on texts, on ideas and sounds that have been written down and thought about. It is very similar to how you talk and write. What has captivated you to the degree that you want to turn this into a work of art? J.T.: I wanted to say something else as well. when i was in kassel two years ago for Documenta (13), the most interesting works for me then seemed to be those that incorporated sound. for example, a purely acoustic installation by Susan philipsz at the end of a train platform in kassel, which used a composition written by pavel haas while he was in a nazi concentration camp. if we move ahead a bit, there was this idea for the exhibition where i’m the joint curator with zane onckule to exhibit Susan philipsz’s work as well, because trains full of prisoners also left for riga from platforms in kassel during the Second world war. this idea won’t come to fruition, either, but it will materialise in my book, in which there is an image of the kassel platform and distant station buildings photographed by me, and in the picture next to it are railway lines at the torņakalns station in riga – a very similar landscape, where we could listen to philipsz’s work. It is clear that today the designation “visual art” can no longer be used as a concept that excludes acoustic or performance aspects. Such divisions cannot be strictly drawn. they might still partly exist with people who are consumers of art: some go to the theatre, others to art exhibitions; obviously, we all, more or less, go to a variety of events, but there is nevertheless one main thing on which we focus the most attention. Art has an advantage – in discussing the avant-garde and radicalism, starting from the revolutionary turning point in the 1960s, art was the most radical. for example, there are very few conceptual works in music, because the fascination with sound is too great – just a few conceptual scores by la monte young in the 1960s and a few other individual examples. L.M.: Perhaps radicalism disappears in music through the many intermediaries between the composer and the listener, because the composer is dependent on the interpreters of the music. What if conductors, musicians, orchestras and managers of places where music is played don’t like it? In art, a direct connection existed between the artist and the viewer for quite a long while, even in the 1960s that you mentioned. At the moment, though, one can see a “bloating” of art institutions, which leaves an unfavourable impact on the course of the development of art. J.T.: In reality, if we transform music into a concept, we don’t need a conductor or an orchestra; we need a sheet of paper on which to write it down. And then someone can execute it: “draw a straight line and follow it.” At the fluxus festival in wiesbaden, nam june paik immersed his head in a pot full of ink and tomato juice and then drew a line on a roll of paper on the floor. fluxus is a movement that combined the musical with the visual and performance. consequently, i was interested in this opportunity offered by art, namely, to work with sound. but you asked me.... L.M.: What captivates you so much that you’ve decided to proceed with it? J.T.: I was invited to participate. i’ve written something about utopia, thought a bit about it.... | |

Armands Zelčs. Publicity image of Aspen – Kemmern exhibition | |

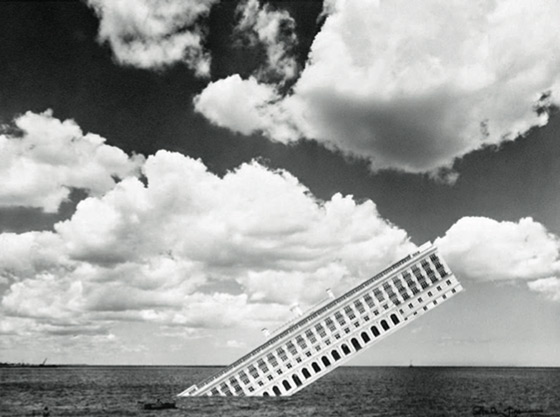

| L.M.: So, your activities and thinking up till now has engendered trust in the curator. J.T.: Possibly, but theoretical and artistic thinking differs quite markedly. when you speak, you think a bit differently. then, when you write, you do it a little bit differently again. when you want to put a text on a wall or to paint, or record and put it into a visual art context – that’s something different. And that requires constant work, because it’s difficult the first time. in doing it, a lot becomes clearer. Here, I’ll permit myself to insert an e-mail as a note. I received this letter from Jānis the following day at lunch time. “Seeing as māra Ķimele had mixed up the recording times due to caring for her dog, who had been bitten by a snake, a free moment has arisen which i don’t know how to use – merely to ponder about something. See, it came to mind that when talking about how i feel in the role of an artist, i didn’t let you know the main difference from the usual work as a writer. namely, in writing, you determine what is going in the text, yours or someone else’s. i translate how i believe is correct, i write what i think, keeping this or that quiet or concealing it behind rhetorical figures. of course, i listen to what Jana (Taurens’ wife – L. M.) or the editor says. but as an artist.... even though it seems it’s the same kind of work with a text, you are nonetheless connected, for example, with the people who will read it for an audio recording. you have to take into account their time, their rhythm of life, who they are, and how and in what language to address them. this is unusual for me as a loner; in some respects it’s like heavy physical work, breaking stones, even though it’s still included in the ancient category of artes liberales.” L.M.: Before I came to see you I tried to prepare myself a “safety net” and turned to friends that we both know with a request for them to send me a question that is meant for you. I wrote to them in this way, too, that I was going to have a conversation with “Jānis Taurens, whom we both know” and that my passion is to think up games and rules. So that it appears that I am leading the discussion a little, there is this element of “questions from readers” from me. And, see, I could finish this part of the discussion about you – the artist, with this “question from a reader”: should an artist be able to tell us (describe in writing) what his/her work of art is about? J.T.: An artist has to be able to talk about a work of art. L.M.: How much should an artist be able to tell us what the work of art is about? J.T.: It is like with the woman that you love: if you are unable to tell her that you love her – language is one of the greatest tools for seduction – then it won’t come to pass, nothing will happen. As i already said, it is hard to talk and it has to be learned, but i, obviously, don’t like the word “think”. At some point i observed a certain asceticism; i didn’t use this word for a few years. i have now improved my mental health enough and can allow myself to use it again. if we accept that thinking is closely linked with language, then we can’t develop thinking without the use of language. thinking is undoubtedly also linked with fantasy and imagination, which is very important in art. Some may say intuition, but “intuition” is another unclear term, often used and misunderstood. there is a simple usage i have decided to use, expanding the way finnish philosopher georg henrik von wright uses it when he talks about language intuition. von wright, in developing modal logic and formalising the usage of some words, wrote “my intuition says that this could be like this or that”. what is this intuition? it is the practice of language, nothing more. therefore, intuition in its broader meaning is that which you have accumulated while working in some field. in art, too, there isn’t intuition without language – reading, writing and talking. L.M.: Is intuition a category that you either have or don’t have, or can it be developed? J.T.: We can’t access thinking as such, but we can observe how a person talks, how he/she writes and how he/she acts – it reveals how the person thinks. we also can’t access intuition, but, when a person creates a work of art, he/she has to continually make some sorts of decisions, choices are made – and intuition is expressed in every decision. A decision has to be made regardless, in the same way as when using language. they may not have any language practice, but a person will say something, and this will be his or her language intuition – very narrow, inadequate, and the result could be misinterpreted or laughed at. i think that intuition has to be powerful, so that the choices are interesting. in the context of choices, there’s another instance – we can slip into accepting the decisions of others. it’s not possible to evade this in all cases. L.M.: To intuitively accept someone else’s intuitive experience. J.T.: Yes, but we don’t know what their experience was like, what their goals were. it’s possible that their intuition was meant for other goals; you accept it, but perhaps their goal was to directly influence you, and you become.... L.M.: ...a victim. J.T.: Yes, a myth. Another equivalent story – a myth (mythos), if we refer to barthes – you become a consumer of myths. therefore, you have to know how to say something. this is not the time to remain silent. L.M.: In the “readers’ questions” I noticed a kind of interconnection – a number of readers, in one way or another, wanted to ask you about “comprehension”. I’m almost sure that each of them has discussed this with you more than once, but maybe there’s something very captivating in the way that you talk about it. J.T.: Or maybe incomprehensible. L.M.: Possibly, but the question I received was fully comprehensible: should what you read be comprehensible? J.T.: Yes! Except there isn’t one correct comprehension of it. you should understand it. there are a number of things here about that issue of comprehension. i remember when i was studying architecture – that was in the Soviet period – we were lectured on aesthetics and something from “diamat” (dialectical, historical materialism). the lecturer’s surname was rutmanis, and i understood that his first name was kārlis from an article by Ansis zunde, in which he wrote about rutmanis very colourfully. he talked independently of the title of the subject; he had these little sheets containing quotes, and he was the first to mention barthes, whom nobody had heard about at the time. he got very carried away while lecturing, sometimes suddenly raising his voice and almost shouting. everybody said that they were very captivating lectures, but that they couldn’t understand any of them. i was the only one who tried to take notes, but unfortunately i destroyed the notes afterwards, so that i wouldn’t have piles of paper. but there was one result – i enrolled in philosophy. So perhaps the first understanding is the one that piques the interest. returning to art – a work of art is like a spur for thinking. the reflection process or impression isn’t just a kind of emotional excitement; it is a spur for you to think and read further about it. comprehension in reading? poetry is a kind of interesting instance. in poetry, the musical aspect and rhythm moves ahead of the meaning. but comprehension can still be in the background at times, like in the case of the language utopia described by barthes, when there is the moment of droning. comprehension is also an important concept in the philosophy of language. [..] L.M.: Please reveal your curatorial concept for the Aspen–Kemmern exhibition. J.T.: A lot of different texts have been created over the course of the project, and at the moment it doesn’t interest me to remember them.... i’ll try to formulate them anew.... And Taurens told me about the source of inspiration – the 1960s American multi-media publication Aspen and its Issue No. 5/6, which was dedicated to conceptualism. He mentioned that Barthes’ essay “Death of the Author” was published in it, in English, even before its release in French. We touched on the theme of the relationship between rural areas and urban centres. Ķemeri, because it characterises our nation’s politico-economic situation, both now and in the 1930s, when the big “ship” was built. But the discussion remained on the recording; I simply got tired of transcribing it. I still had the conversation about the book, conceptualism in latvia / preconditions for thinking, ahead of me, but as both of us suspected that the complete discussion wouldn’t fit in the magazine, Jānis let me use fragments from the book’s layout 1:1, which now follow... | |

| go back | |