|

|

| The tactile quietness of Vija Celmins Laine Kristberga, Screen Media and Art Historian | |

| Anthony d’Offay, a british art collector and curator, says about vija celmins: “there’s a waiting list ten years long to get a work of hers. she is one of the most sought after and most famous women artists in the world. she’s like frida kahlo, except she’s completely quiet. but she’s of that importance and quality.”1 i would rather agree with andrea d. barnwell, a researcher from the art institute of chicago, who compares celmins restricted palette and meditative quality to the minimalism of agnes martin.2 No matter what parallels the foreign art specialists would draw, the name of vija celmins has been heard quite rarely in latvia. currently, in the media celmins has been labelled a ‘world-famous artist’, but this, too, is perhaps the credit of the recently released documentary film Teritorija Vija Celmiņš by the juris podnieks studio. in the united states, celmins works of art are analysed in master’s and doctoral theses3, yet in latvia the works of the newly discovered celmins are mostly known among a few art enthusiasts. spider webs, the ocean, star-filled night skies, surfaces of the moon and desert – celmins art has usually been identified with such drawings and images. however, she is an artist of broad scope who has worked with various media, starting with painting and sculpture and ending with drawing and photography. Celmins emigrated from latvia in 1949, when she was ten years old. her family settled in the middle of the united states in india- napolis, indiana. in the early 1960s celmins moved by herself to california to attend art school. her memories of this stage of her life are related to loneliness and seclusion: “i liked to be alone a lot.”4 during this period the artist spent long hours in her studio, where she painted several paintings in the grey tonality, which later, when working with graphite, became her trademark. these works were focused on banal things found in the studio: a hot plate, a table lamp, a heater, a fan and so on. It should be noted, however, that you will not find bowls of fruit, vases with flowers or carafes with water among these objects. the mundane and very obvious objects selected by celmins do not require a special interpretation. even more so, they could be considered as boring and ‘empty’; muteness and inexpressiveness describe them best, as befits still life, after all. however, this silence so characteristic of the early works of celmins let the artist avoid rhetoric and meaning, emphasising the act of looking, as opposed to interpretation. celmins admits that at this time she was very inspired by ad reinhardt’s essay Twelve rules for a New academy written in 1953, in which reinhardt describes a new vision of painting, primarily grounding it on negation and reduction.5 perhaps this is the reason why the artist sought purity of form, asceticism, intentional limitation and pragmatism: “i hate it when there is too much of a narrative in a painting. then there are references to the outside world. i don’t want it in my painting. i want my art to be located in the space where it’s placed – to compress the image and to create a physical feeling at the exact place where it is, in order that the only reference possible is the work of art itself.”6 Certainly, in the 1960s “everyone was painting objects”; gerhard richter, too, had a painting with a toilet paper roll, too (Toilet Paper, 1965). and yet pop art celebrated the common object most, producing numerous works with soup cans, Coca-cola bottles and washing powder. however, celmins denies that her paintings would resonate with pop art ideas. the artist sees her oeuvre as “old-fashioned art depicting some kind of objects, with an abstract background and illusory space”7. she “feels sick” thinking about andy warhol and draws parallels with the greyish and misty subtlety of the italian modernist giorgio morandi instead, who in a similarly distanced manner painted the objects at hand in his studio.8 | |

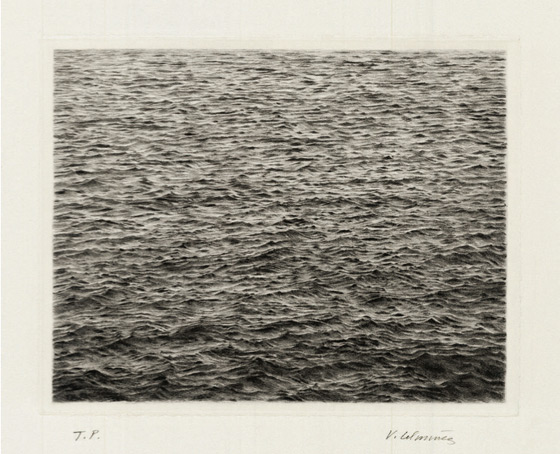

Vija Celmins. Drypoint – Ocean Surface (2nd State). Drypoint. 61 x 48.3 cm. 1985 Publicity photo Courtesy of the artist | |

| Art historian Linda Nochlin mentioned vija celmins in her 1974 essay Some Women realists regarding the new realism movement and compared the creative work of celmins with the linguistic devices in the works of alain robbe-grillet, the representative of the french nouveau roman. nochlin explains that celmins “rapier-sharp realist imagery” can best be compared with robbe-grillet’s “attempt to abolish significance in literature”.9 perhaps robbe-grillet, celmins and morandi have a common interest in outlines and contours as opposed to content and narrative, which is summed up by Morandi: “matter exists, of course, but has no intrinsic meaning of its own, such as the meaning that we attach to it. we can know only that a cup is a cup, that a tree is a tree.”10 When she tired of painting objects, celmins started to look for new sources of inspiration, and her solitary time in the studio was supplemented with walks on the beach and regular visits to the library and bookstores. “i started to search for images that would not be related to something that is already pursued in art or to a certain school or direction in art.”11 gradually celmins began focusing on photography, especially images from scientific sources, for example, the first photographs that were taken in space, whereas from her walks on the beach celmins returned to the studio with pictures of the ocean surface. “when walking my dog and photographing the ocean, i fell in love with the surface. i had photographs of the ocean everywhere, like some kind of objects with surfaces. ugly surfaces, i don’t like the surfaces of photographs – slippery, cold surfaces. but i could make another, my own surface; this is how these things evolved, and i started to use photography....”12 Thus, in 1968 several works were made in which clipped or torn-out images of objects from the second world war were scrupulously depicted, for instance, a gun, a zeppelin blimp, a plane, a mushroom cloud of the atomic bomb, a bombed-out hiroshima and also an envelope with a letter from her mother. celmins states that at first she painted these clippings, but later she decided “the clippings were this wonderful range of grays for me to explore with graphite.”13 it must be noted, though, that the redrawn photograph is not to be understood as a master class in photorealism. a photograph in celmins drawing serves as the representation of the familiar world, yet it is an object and not a form of representation. therefore, the imagery in the photographs contains literal objects, without history or symbolism, without emotions or expression, which celmins achieves with anonymity and a distancing from the actual event and the meaning of the pictured object. A little while earlier – in 1964 – one of roland barthes’ first essays, The World as Object, was published in art and Literature magazine, edited by american poet john ashbery.14 in this essay barthes examines dutch painting and indicates that dutch still life is like an inventory of things, where in the jumble of objects one can find everything from beehives, wine presses and ovens to stable bedding, mirrors, books, medallions and so on.15 barthes suggests that the only way to understand what occurs in a dutch painting is to study every single detail “one after another, from side to side and from top to bottom, as if it were an accountant’s report, making sure not to overlook this or that figure in the lower left, or in the upper right, or off in the background.”16 Although initially it might seem that there is too great a distance between dutch still life and the photograph drawings of celmins, the fact that interpretation and subjective experience is replaced by an act of close viewing and even optical scanning can be attributed equally to both. besides, barthes in his later career also turned to the study of photography, and, from his point of view, a photograph is part of the world of objects. celmins has a similar opinion – for her a photograph is another item in the studio, a two-dimensional still life. “i use a photograph as an object. i use it and i put it in a different context – in the exhibition hall. to me photographs are like found objects. i use them because they are quiet and they are not people.”17 Celmins describes the use of photographs as common objects as the first break in her career as an artist. the second break occurred when she started to draw the night sky and the surfaces of the desert, ocean and the moon.18 this imagery, too, has been borrowed from photographs, yet this time the photographs are not depicted as objects in their own right, and the accurate transfer of the rocks, sand and water onto the paper begins to approach abstraction. what is copied in these works is not the desert or the ocean but the image of the desert or the ocean. this time, too, in order that the spectator does not become entangled in the web of representation and illusion, he or she is encouraged to look closer, because these drawings, too, mimic both the form and the format of a photograph. in order to secure the accuracy of the transfer, celmins sometimes used a grid, but she soon came to the conclusion that it was more convenient to start the work in one corner and then continue to the next.19 The surprising accuracy in celmins drawings of the surface of the moon has been studied by cécile whiting, a professor of art his- tory at the university of california, indicating that “these drawings with their framing white borders and precise, minute graphic marks look like photographs when seen from a distance and reveal their status of drawings only up close”.20 in contrast to the ocean and des- ert photographs, which celmins took herself, the drawings of themoon were based on photographs produced by the most advanced technology of the age. whiting stresses that celmins drawings of the moon surface created from 1969 to 1972 bring to the forefront the collaboration between human and machine, helping to overcome the vast distance that separates the earth from its moon and allow- ing the human eye to examine the details of the distant and alien lunar landscape in a close-up.21 However, whiting’s core thesis in relation to celmins lunar drawings is about the partnership between a cyborg (cybernetic or- ganism) and an artist, where the boundaries merge between “the automated and the handcrafted, the near and the remote, seeing and making, and even masculinity and femininity, to reconfigure vi- sual experience in an era of space exploration”.22 in transcribing with pencil on paper what the cyborg ‘saw’ on the moon – craters, ridges, hollows – celmins reconstructed the physical peculiarities of the moon surface with such precision that these drawings could look like mechanical reproductions. besides, the drawings retained the evidence that the images had been received in the form of electron- ic signals and that they were processed in labs by technicians piecing them together from individual fragments like a mosaic. thus, celmins documented not only the transmitted image but also the process by which it was obtained so accurately and passionlessly as if she were herself a machine.23 Whiting accentuates that in the drawings of the moon surface the pencil graphite covers the paper so closely that the drawn sur- face seems to fit like a membrane.24 this comparison leads to paral- lels with the haptic25 visuality concept proposed by media theorist laura u. marks.26 pursuant to marks’ theory,27 haptic visuality is an act of looking based on the sense of touch in which the eyes metaphor- ically function as organs of touch. haptic visuality and optical visual- ity are not completely opposed, but they exist on opposite ends of the same spectrum. marks describes haptic images as images that require a haptic act of looking, because optically these images are hard to perceive – they can be grainy and distorted. because in such images we cannot identify the other space and other figures, our haptic look rests on the surface of the image as opposed to perceiv- ing its depth dimension. we sense the image with our body, as if this other surface was another layer of skin.28 | |

Vija Celmins at the installation of the Double Reality exhibition Photo: Kristaps Kalns Publicity photo | |

| In fact, haptic visuality can be ascribed to all celmins surface drawings, including her works of the desert, the ocean and the starry sky, and their haptic visuality is perhaps best expressed through a comparison with the texture of fabric. the perceptual tension between an image and its representation, between the illusory depth and flatness of the surface, are subjects that celmins examines in series over and over again. “the material, charcoal and pencil and paper, are bigger players in the night sky pieces. the work is much more abstract, and even though your mind says this is a deeper space, i think the uniform nature of the graphite sitting on that surface keeps you engaged in the flat plane. there really is no depth to it. (..) the work gets a little flatter as time goes by. for instance, in the later ocean work from 1977, the image lies close to the paper and describes the surface of that paper as much as anything.”29 In 1977 celmins turned to other forms of art, namely, sculpture. in the framework of the project To Fix the Image in Memory I–XII celmins took stones from her walks in new mexico and created their sculptural duplicates in bronze and paint. similarly to photographs and clippings from magazines, the stones were also found objects for celmins. just as the surface drawings, these ‘twin brothers’ of the actual stones made the spectator look closer. because both versions were shown in exhibitions – the geological objects formed in nature and the man-made duplicates – the spectator’s task was to ask whether it was possible to see a distinction between an original and a copy, giving rise to speculations about an object in nature and its representation in art. celmins admits that in her works of bronze stones she wanted to find out how much she was able to see herself, without projecting someone else’s gaze, but to test her own ability to see and make “as if there were some secret to be discovered only there”.30 The latest points of reference in celmins oeuvre are intricate drawings of spider webs. they, too, are based on scientific images found by the artist at the natural history museum, which served as sources of inspiration for new surface drawings. “i thought these webs described the space i always wanted to describe – a surface that has small facets that rigorously account for and record every intersection; a lived-on surface.”31 samantha rippner, a curator at the new york metropolitan museum, writes that the spider webs drawn by celmins make the spectator contemplate the product of a pains- taking effort – by both the spider and the artist.32 celmins herself admits that it is not difficult for her to identify with a spider: “i’m the kind of person who works on something forever and then works on the same image again the next day.”33 american art critic peter schjeldahl also agrees with this statement, defining the artist’s spider webs as her “self-portraying symbols”.34 Celmins is an artist-constructor who, similarly to a naturalist, curiously examines the surrounding nature and the world of objects. british philosopher timothy williamson explains that to be a naturalist is to look for evidence and proof and to be able to associate one- self with such values as “curiosity, honesty, accuracy, precision and rigor”.35 to some degree the works by celmins seem like an experiment in which the artist is testing herself and the spectator; they play a phenomenological game of perception, making the spectator inspect the work of art near and far and oscillate between the optic and haptic perceptual modes. thus, celmins art is process-orientated art – it is both the thinking process and the time-consuming ‘copying’ process during the making of the work of art as well as the activated and decentralised viewing process that the spectator is subjected to. Translator into English: Laine Kristberga 1 www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/video/artist-rooms-vija-celmins (accessed 22.05.2014) 2 barnwell, andrea. explosion at sea, 1966, by vija celmins. Modern and Contemporary art, vol. 25, no. 1. chicago: the lannan collection at the art institute of chicago, 1999, p. 30. 3 much of the factological information and data on vija celmiņa for this article were obtained from katie e. geha’s doctoral thesis Like Life: Data, Process, Change 1967–1976 defended in 2012 (accessible at: repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/etd- ut-2012-08-6317; accessed 22.05.2014). 4 vija celmins, artist talk at the menil collection in conjunction with the exhibition Vija Celmins: Television and Disaster 1964–1966, november 19, 2010. from: geha, katie e. Like Life: Data, Process, Change 1967–1976 [doctoral thesis. austin: university of texas, 2012], p. 28. accessible at: repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/etd-ut-2012-08-6317 (accessed 22.05.2014). 5 grant, simon. celmins, vija. thinking drawing [an interview], january 1, 2007. Tate etc., issue 9, spring 2007. accessible at: www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/ thinking-drawing (accessed 22.05.2014). 6 elita ansone. fragmenti no elitas ansones intervijas ar viju celmiņu. rīga 2014 – eiropas kultūras galvaspilsētas programma (april – june, 2014), p. 8. 7 ibid. 8 ibid. 9 nochlin, linda. some women realists. in: Super realism: a Critical anthology. ed. greg- ory battock. new york: dutton, 1975, p. 77. 10 wilkin, karen. giorgio morandi. in: Giorgio Morandi: Works, Writings and Interviews. barcelona: ediciones poligrafa, s. a., 2007, p. 131. 11 fragmenti no elitas ansones intervijas ar viju celmiņu, p. 9. 12 ibid. 13 vija celmins, interview by chuck close. in: Vija Celmins. ed. william s. bartman. new york: a. r. t. press, 1992, p. 12. 14 published for the first time in france in 1953. 15 barthes, roland. The World Become Thing. trans. stanley geist. art and Literature, vol. 3 (autumn–winter, 1964), p. 153. 16 ibid. 17 fragmenti no elitas ansones intervijas ar viju celmiņu, p. 9. 18 both breaks can be dated to 1968, according to katie geha’s discussion with vija celmiņa on august 2, 2011. from: geha, katie e. Like Life: Data, Process, Change 1967– 1976 [doctoral thesis. austin: university of texas, 2012], p. 58. accessible at: reposito- ries.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/etd-ut-2012-08-6317 (accessed 22.05.2014). 19 ibid., p. 62 20 whiting, cécile. it’s only a paper moon: the cyborg eye of vija celmins. american art, vol. 23, no. 1 (spring 2009), p. 37. 21 for some drawings celmiņa used the first close-up photographs of the moon surface from the soviet spaceship Luna 9, which landed on the moon in february 1966; for others she used photographs received from the american spaceship Surveyor 1, which landed on the moon several months after Luna 9 and sent 11,000 photographs back to earth, includ- ing the first colour images. 22 whiting, cécile. it’s only a paper moon: the cyborg eye of vija celmins, p. 47. 23 ibid., pp. 42–47. 24 ibid., p. 52. 25 from greek – ‘touching’, ‘connecting’. 26 marks, laura u. Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media. minneapolis: univer- sity of minnesota press, 2002, pp. 5–6. 27 whereas laura marks refers to the work a Thousand Plateaus by gilles deleuze and felix guattari. 28 transliteracies.english.ucsb.edu/post/research-project/research-clearinghouse- individual/research-reports/haptic-visuality-2 (accessed 22.05.2014). 29 grant, simon, celmins, vija. thinking drawing. 30 vija celmins, p. 20. 31 grant, simon, celmins, vija. thinking drawing. 32 rippner, samantha. the prints of vija celmins. new york: the metropolitan museum of art, 2002, p. 9. 33 www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/celmins-web-1-ar00164 (accessed on 22.05.2014). 34 schjeldahl, peter. dark star: the intimate grandeur of vija celmins. The New yorker, june 4, 2001, pp. 85–87. 35 williamson, timothy. what is naturalism? new york times, opinion pages, september 4, 2011. accessible at: opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/04/what-is-natural- ism/ (accessed 22.05.2014). | |

| go back | |