|

|

| Troubles of freedom in twelve likenesses Santa Mičule, Student, Art Academy of Latvia Exhibition Critique and Crisis: Art in Europe since 1945 17.10. 2012.–10.02.2013. German Historical Museum, Berlin 15.03.–02.06.2013. Palazzo Reale, Milan 28.06.–03.11.2013. KUMU Art Museum, Tallinn | |

| The Critique and Crisis: Art in Europe since 1945 exhibition, which was organized with the support of the European Union, is on show in Tallinn. About a third of the works which were shown in the original version of the exhibition in Berlin have, unfortunately, not been included in the KUMU art museum exposition. Even so, it could be the first art event in the Baltic region where such a broad selection of stars of late 20th century European art can be seen all in the one place. Damien Hirst, Yves Klein and Gerhard Richter are only some of the artists. Luckily the exhibition isn’t one where the participants’ names overshadow their own creations, as at our latitude one comes across such an active, socially critical tendency in works more rarely than one does icons of contemporary art. Attention should be drawn to the initial hopes of the creators of the exhibition (curators Monika Flacke, Henry Meyric Hughes and Ul- rike Schmiegel) to devise an exhibition where art created during the time of the Iron Curtain and the Cold War could be viewed outside the usual contrast between the West and the East. As a result, the exhibition has different accents: it mainly covers artists’ abilities to react critically to the events of their time, making art a place of sanctuary for ethical ideals and the voice of society’s conscience. One of the guiding motifs is an assumption about the artist being an especially sensitive member of society, able to generalize their specific social or existential experience in expressive art images. Although artists from Western Europe dominate the exhibition numerically, the curators have been able to avoid the arrogant marginalization of the East which often manifests itself when interpreting artistic material purely from the point of view of achievements in the history of Western art. A nonhierarchical approach should also be maintained by view ers as well, forgetting for a moment the myths generated by the glob- al art market about the superiority of individual artists or regions. At its previous stopping off points in Berlin and Milan, the exhibition was shown under the title Desire for Freedom. In Tallinn, the title underlines the original source of inspiration – historian Reinhart Koselleck’s dissertation ‘Crisis and Critique: Enlightenment and the Pathogenesis of Modern Society’ (1954), in which he emphasizes the inescapable connection between both processes and their signifi- cance in the creation, development and also the survival of modern democracy. The nonexistence of a mechanism of selfcriticism in so- cialist countries is seen as a cause of the collapse of the Soviet Union, whereas the socalled capitalist state understanding of democracy up till now has been shaken by ever new forms of social movements, geopolitical changes and other sorts of crises(1), making one doubt traditional values as a suitable reference point for survival in the mod- ern world. The change in the title hasn’t significantly influenced the content of the exhibition, but Desire for Freedom seems more accurate and a more readily understood description for the principles which have structured the selection of works and authors. The exhibition’s thematic core could be the common and the different in searches for the expression of the desire for freedom in the Western and Eastern regions of Europe. The division of this search into 12 thematic sec- tions creates the drama which highlights the most problematic zones of interaction in today’s world and in human rights (resistance to systems, military conflicts, restrictions on physical relocation, childhood traumas and other), defining the notion of freedom in the concept of the exhibition at the same time. | |

| |

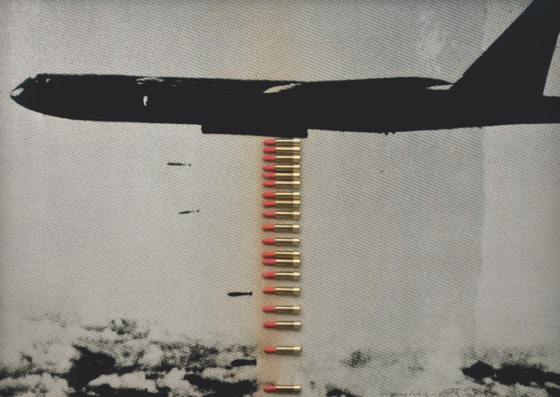

| The circular arrangement of the exposition structures the ex hibition into an accessible, understandable form and makes the logic of the space correspond to the thematic development of the works. For example, the theme of the geographical environment is followed by the problems of urban space, which is continued by a compilation of imaginary spaces, and so on. The exhibition’s overall image is uniform in this way, and its internal development is similar to the continuity that relates to the progress of historic events. It is signifi- cant that the first place where the exhibition was held was a history museum and not an art institution, and in the exhibition itself, the impression is created that art as an aesthetic phenomenon has at times become secondary for curators. Anybody who knows a little about the past 70 years of the history of Europe will find the references to specific historical situations or circumstances in the context of each work easily readable. In the vision of the artists and the curators, the ideals of freedom, equality and justice dominate. From these, the resultant objects of critique serve as a portrayal of Europe, with the art works transforming into an interpretative testimony of the era. The exposition begins with a critique of the Enlightenment and the guillotining of its personification in the work The Age of Enlight ment – Adam Smith (2008), created by Yinka Shonibare, whose paradoxical image of a headless intellectual calls to mind reflections on the ideal of rationality by Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno. Characteristic of the Age of Enlightenment was the transformation of this ideal into its own denial or blind automatism which, in the end, led to the crimes of the Nazi regime (it is a little surprising that the theoretical legacy of both philosophers was not included in the exhibition’s theoretical base). The Second World War, as psychologically the most serious 20th century catastrophe, forms one of the exhibition’s most significant points of reference and is also inescap- ably connected with the year 1945 which is included in the title as a chronological boundary. Despite the period of time that has passed, reminders about the history of Nazism in the exhibited works contin- ue to be topical. For example, Anselm Kiefer’s series of photographs Occupations (1969), in which the artist has portrayed himself in a va- riety of city and country landscapes with his arm raised in a Nazi sa- lute, has not lost its provocative nature even from the point of view of the 21st century viewer. Meanwhile Christian Boltanski’s installation with enlarged and illuminated portraits of graduates of Vienna’s Jewish Gymnasium reconstructs the events of the Holocaust as an individual, not a mass tragedy – a view which still appears to be marginal in contrast to the official remembrance day and place rituals. The silkscreen series Under the Estonian Sky (1973; during Soviet times, the name Estonia was deleted from the title of the work) by Estonian artist Raul Meel is, in terms of references, one of the most multilayered works in the exhibition. Using the symbolism of the Estonian national flag which was banned during the Soviet years, Meel’s work demonstrates escapism as one of the most widespread forms of spiritual survival under circumstances of political oppression. The creators of the exhibition have been able to graphically show (for example, with Lucio Fontana’s cosmographic abstractions), that the construction of a desired reality and the taking of refuge within it was and is the most widespread “diagnosis” in the culture of democratic countries as well, using a freer, but consequently also less expressive artistic language in terms of symbolism. Distancing itself from the direct consequences of historically political collisions, the critique by the artists selected for the exhibition is to a large degree directed at various aspects of consumerism. In the works exhibited in a section called “99 cents”, the artists refer most directly to symbols of the good life. The effect of a consumerist lifestyle on natural resources has been brought to the fore in a number of works guided by ecological thinking. For example, Christo’s Wrapped Oil Barrels (1958–1959) is exhibited as a memorial to the senseless exploitation of the environment which gradually leads to its destruction. The artist Absalon, who is of Israeli origin, has focussed on another aspect of environmental change: in the video work Solu tions (1992) he has developed a cell whose compact size has been adapted for life in big cities. The intensified desire for functional- ity is transformed into its opposite and the tightness of the space doesn’t allow it to be inhabited, neither physically nor socially, subjecting its inhabitants to urban isolation. Psychological portrayals of the contemporary person dominate in the exhibition’s last two sections “Selfexperience: Testing the Limits” and “The World in Our Heads”. Jean Dubuffet’s artistic assem- blage turns an anthropomorphic portrait into the portrayal of a to pographical landscape, which reminds one of the images of deformed people that are characteristic of postwar culture, expressing the ru- ined futures caused by war injuries. Selfcriticism as a critique of the times appears, for example, in Francis Bacon’s selfportrait Fragment of a Crucifixion (1950), which could also be interpreted as a reference to the legislation unsympathetic to homosexuality in Great Britain at the time the work was created. A fundamental hallmark in the search for identity is the expansion of the “I” in the dimension of art, which is demonstrated in Oleg Kulik’s and Günter Brus’s physiologically extreme video performances where they have attempted to find and overcome the boundaries of their identity. Translator into English: Uldis Brūns (1) Flacke, Monika. The Journey. In: The Desire for Freedom:Art in Europe since 1945. Ed by Monika Flacke. Berlin: German Historical Museum, 2012, p. 15 | |

| go back | |