|

|

| Like meeting an old friend again... Jānis Borgs, Art Critic Janusz Golik. To be in the Right Place 15.05.–31.05.2013. Agija Sūna Art Gallery | |

| “God created man and Artist. To the first He gave reason, but the second was also endowed with talent.” With this motto Polish graphic designer Janusz Golik makes himself known in the intro- duction to his exhibition booklet. And in this context, logically, the stated cannot be applied in general to all the world’s artists as a whole, but only and directly to the author of the exhibition himself. It even brings a little excitement – the master has put to one side the usual expected modesty (saying – what can I?) and has decided for himself, without waiting for the possibly inconsistent opinions of critics and viewers, to duly remind us about the “unique” gifts of God – brains and talent – that he has received. So there’s no more room for doubt. If we go into Biblical dimensions, however, let’s also recall doubting Thomas and what he said: “If I don’t see the marks of nails in His hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into His side, I will not believe.” We can compare art to a jewel, the authenticity of which any “sceptic” can check: by scratching it, biting it, or testing it with the acid of doubt. Even if the first glimpse of the exhibition motivates us, without worrying about it too much, to concur with Golik’s pathetic declaration. Behold! – this is real talent here. Test 1 – “In the Common Camp” project But the first glance, already at that very first moment, makes us recall the commonly experienced and kindred past. We once had, in many ways, a similar recent historic experience and background of a communist totalitarian existence. The differences were only in the nuances, and in the regimes of the various separate barracks in our common prison camp of socialism. It seems that Stalinist oppression, at least in the cultural field of Poland, was a little more le- nient, and that the rooster of freedom crowed there about an hour earlier. Here the delay in development of our historical processes was about ten years. Janusz Golik was only just being born around the time when Stalin, the great ruler of the “common camp” and the “sun over the brotherly nations”, finally ended up six feet under. But in Poland, way back in 1953, the activists “of the first hour” clearly saw the new cultural dawn in the West and who were already on the move. And, of course, in our own rich prewar experience as well, which the Red ideologues of the time tended to describe as decadent and “bourgeois formalistic”. The shoots of a cultural renaissance sprouted in many fields of art, breaking through the asphalt of Soviet ideology and censorship. Quite early in the post-Stalinist period, Polish painting, sculpture and graphic art was already rife with expressionist passion and surrealistic metaphors, no longer could you find any trace of the art dogmas cultivated by Moscow there. | |

Janusz Golik. Casanova. C-print on canvas. 50x70 cm. 2008 Publicity photos Courtesy of the Agija Sūna Art Gallery | |

| Here in Latvia, our neighbour’s modern culture appeared most strikingly in the rare Polish cinema surprises. But for those in the know, revelations also came from the famous Polish poster (and grap hic art) school, which only arrived here in the early 1960s, mainly via the officially issued People’s Republic of Poland periodicals which you could subscribe, as well as buy at Press Association kiosks. Because an ideological thaw, and a conditional cultural liberalization had set in. The Kremlin finally opened up some fresh air ventilation shafts in the Iron Curtain. New, previously unseen graphic expression poured from the pages of the Польша, Przekój and Szpilki magazines, but the Projekt art magazine’s rebellious volcanic eruptions swirled across every- thing. In Poland this publication had already evolved in the mid 1950s, when here in Latvia modernist ideas were still wandering around in a deep fog of uncertainty like a hedgehog. The magazine amply revealed the avantgarde art processes rooted in Western cul- ture, not only in its own home country, but also beyond the Iron Curtain. From the 1960s, it became a “handbook” for every contemporary thinking artist in almost the entire Soviet Union. Projekt became the main window for viewing the art panorama of the West, and the magazine developed into one of the most significant catalysts for the development of avantgardism in the whole territory of the USSR. Test 2 – Who are you, Janusz Golik? In Polish graphic and poster art of that time, during the era of Polish communist boss Wladislaw Gomulka, such supernovas as Henryk Tomaszewski, Roman Cieślewicz, Hubert Hilscher, Józef Mroszczak, Jan Lenica and others were already shining brightly. This was a great generation of art pioneers, who, consistently following modernist cultural tradition, were able to offer previously unseen innovations and to unify art values with the spirit of social protest and rebel- lion so characteristic of the proud Poles. Though one should timidly add – not without the blessing of those in power, and their attempts to use the energy of modernism in “turning the windmills” of official Poland. In this context, Janusz Golik belongs to the socalled third gen- eration of the Polish poster school, the one that could quite peace- fully enjoy the fruits of comfort and achievement which the previ- ous aspirants had fought for. His studies at the Warsaw Art Academy glided along in the 1970s. Those were completely different times, incomparably more open to the world, even though still quite unsettled. Finally, Solidarity matured through the unrest, Lech Walensa rose and the first ever Polish pope, John Paul II, brought holy tidings to the world. Even though politically the country was still closely aligned to the Moscowcontrolled Communist Bloc, culturally it had already long belonged to the free world. Moreover – here in many ways Poland found itself in front line positions, and even set the global trend in various fields of art. Graphic, as well as poster art, was one of them. Janusz Golik was truly fortunate in having the opportunity to obtain his professional knowledge with Polish poster art grand masters and internationally acclaimed classics – Maciej Urbaniec and Henryk Tomaszewski. Urbaniec had already attained international success in the 1950s, for example, being published in Switzerland’s famous Graphis magazine in 1957. He also gained recognition with his theatre and circus posters. Urbaniec’s famous circus poster Mona Lisa is held at the MoMA in New York. Professor Tomaszewski, meanwhile, had been garnering world fame in poster art since 1948. In the exhibition at the Agija Sūna Art Gallery, Janusz Golik with his To be in the right place proves that he belongs to the new classics who were able to take over the mantle of the nobly maintained tradi- tion of endeavour. In actual fact, we saw here not just the mastery of one particular individual, but also clear loyalty to a certain school. A truly political one, but its influence has left its mark throughout the world, including the Riga poster school which developed during the Soviet period. | |

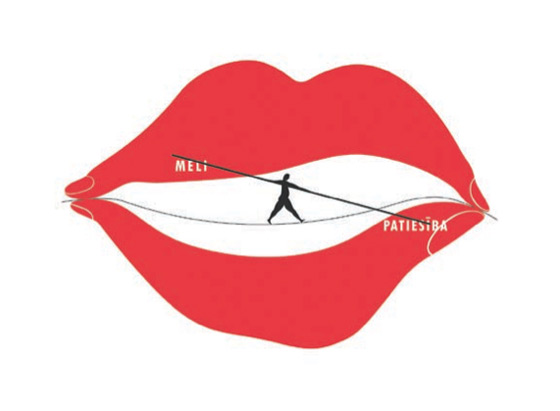

Janusz Golik. The Truth. C-print on canvas. 50x70 cm. 2013 Publicity photos Courtesy of the Agija Sūna Art Gallery | |

| One feature of Janusz Golik’s exposition should be noted – as opposed to our habit of separating academic graphic art from graphic design quite strictly, and poster design as well, in Poland the concepts “graphic artist” and “graphics” are evidently interpreted more loosely and universally at times. In every respect we can say this about Golik, who, after graduating from the academy in 1978, started up commercial activity with businesslike energy and established his own studio Grafik Janusz Golik which now also houses the Galeria van Golik. A keen sense of humour is evident in many of the master’s works, even in the serious ones and those created with a poker face. In any case, he only had to change the last two letters in the name van Gogh, and in van Gogh’s selfportrait with its missing ear on the gallery’s poster we can clearly discern van Golik’s own face. The pre- viously mentioned graphics studio, in turn, offers the production of logotype, poster, booklet, calendar and advertising campaign etc. design. Long ago, during the time of “our dear” Nikita Khrushchev, a popular spy film ‘Who are you, Mr Sorge?’ suddenly appeared in the USSR. A similar question now arises: “Who are you, Janusz Golik?”. Clearly, not a spy (although, if one plays along with Golik’s own humour – who and what can safely attest to the Lord’s paths and laby- rinths?), but neither is he an academic graphic artist either. Here the graphic artist is a man with a wide scope of activity. Almost like in the Italian Renaissance, whose geniuses successfully focused on what- ever was in demand. And there was some kind of mystical connectedness – many of the Quattrocento and Cinquecento masters were united in a fraternal guild of doctors and pharmacists. So let’s not be shy about giving Janusz Golik the title of graphic designer. Surely it has been justifiably earned, with him having forged virtuoso works in all of the mentioned fields and categories of graphics for almost 35 years. Test 3 – Golik's line, colour, symbols In Janusz Golik’s “right place” exhibition, the pages of graphics at first glance could have seemed like posters. Clearly defined signs or symbols, on a just as posterlike smooth surface in stopsignal red or black colour, are set out at the centre of the composition planes. A strictly limited colour palette (red, black, white) and posterlike laconic expression of form lead to associations with the declarative assertiveness of the commercial advertising and logotype world. Al- though, for example, let’s recall this same colour code and ascetism of form in the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich and his contempo- raries, or in Lissitzky’s famous poster Бей белых клином красным!. In the 1920s, such revexpression also meant belonging to the Left and opposition to the entirely despised bourgeois culture. How ever, in Golik’s graphics political motivation cannot be found in such an open way. This is manifestly artistic – his personal colour minimalism in the name of expressive maximalism. If we cling closely to academic, traditional views, it is only the lack of text or slogans that allows the pages of graphics he offers to be perceived as “great art”. And precisely this, here, would be completely mis- placed. Erroneously held under suspicion of being Leftist, van Goliks should be completely exonerated, if we begin to examine the for- mal shapes of his drawings, where we almost have to agree with the old Bolshevik pureminded view – this one really has drawn on and erupted from decadence. In the lines of Golik’s posterlike figures one can rather sense the suppleness and sensuality, in places even the perversity, of Aubrey Beardsley. This is motivated by the emphatically erotic subject matter of the sketches. The passion satu- rated with drama does , however,get as if intelligently ornamental- ized. In almost every graphic work, a pictogramlike entanglement of two figures is portrayed with barely hidden accents and allusions to the beautitful presence of genitalia. A rhyme recited by boys of puberty age springs to mind: “In the corner colours blare, a sexual act is hidden there”. Golik’s eroticism, even with all of his perfection of lines, is far from that which we find in the world of, say, Botticelli, Ingres, Klimt or Mucha. There, every- thing was based on the sensitivity of the “living hand” and was decked with a lining of academic skill. Golik’s lines, on the other hand, are designed as in a draughtsman’s drawing, in the direct sense, almost like they were extracted with the help of a template. And even their existence is largely reduced to the outlines of silhouettes. I have also come to observe a similar passionless “draughts- manlike” treatment, for example, in the graphics of a number of Estonian classics (Leonhard Lapin, Tenis Vint and others). You could say that it’s a kind of feature of the technocratic age. But this is not the place for regrets about the past, and one doesn’t have to search for exculpatory words. It’s another aesthetic, where passionate feelings inhabit a cool flow of lines – like in the body of an aero- plane, toaster or refrigerator. Cool – that’s the slogan of the age! Janusz Golik’s posterlike graphic compositional solution is always simple, clear and laconic as a road sign. To be absorbed like a blow to the head. The possible condition of shock is alleviated by a therapy of muted humour and plaster. If our overwrought sensors are still able to perceive them. At times something “revolutionary” flashes in the interpretative pathos and balletlike poses of his hu- manoid figures – like in Delacroix’s La Liberté guidant le peuple. A generalization in a symbol is Golik’s graphic language which he, sup- posedly, has used in the realm of poster art. What has been cultivated there and recognized as good is continued in his graphics pages. An exact and concise symbol replaces the “weeds” of volubility of the lit- erary message. When looking at his peoplesigns, one thinks also of our graphics and poster grand master and philosopher in art, Ilmārs Blumbergs, whose “trade mark” and constantly repeated motif is the “embryoperson” – a humanoid interpreted in the silhouette image of a Turkish bean or kidney. There isn’t any doubt that both artists, Golik and Blumbergs, have during their study years “fed” from the one cultural bowl – Made in Poland. One directly, the other – at a distance and indirectly. Janusz Golik’s exhibition truly brought joy, like a small and rare collection of jewels, genuine and endowed with a spiritual kinsman’s aura of affinity. In his preparations for the exhibition in Latvia, the artist has demonstrated a quite unaccustomed gesture of respect to- wards our public. In a number of works where the original included text in the Polish language, at the Riga exhibition the texts were in Latvian! This means that we were presented not with works off the shelf that had been done before, but with originals of works that had been adapted specifically and specially for exposition in Latvia. It may seem a trifle, but we notice this, and we don’t forget it. Because the core value in a relationship is respect. And as to the master, Ja- nusz Golik, we acknowledge our respect for the flourishing of talent. It was truly was destined to be in the right place. Translator into English: Uldis Brūns | |

| go back | |