|

|

| Accumulating energy Eglė Juocevičiūtė, Art Critic, Curator oO. The Lithuanian pavilion at the 55th International Art Exhibition of Venice Biennale 31.05.–24.11.2013. | |

| It will all connect in somebody‘s head in Venice. Some meetings and events that are part of the Lithuanian pavilion exhibition Oo (or oO) in the 55th Venice Biennale had already happened before I talked to the organizers. In their eyes, some parts of the pavilion exhibition happened even before there was an idea for a pavilion exhibition. And it might not end with the closing of the pavilion in November. At this point, there’s no way I can tie all the storylines into one big knot and give you one fluent narrative. The best that I can do is to unravel as many of the storylines as I can and then tie some of them up into some little knots. A few weeks ago, the presentation of the Oo timeline took place in Venclovas House, the memorial housemuseum of one of the most interesting literary families from the Soviet period. In recent times, the housemuseum has become a popular venue for conceptual gatherings, because it serves perfectly as spacetime, taking you away from a busy Vilnius street to an intellectual oasis. The presentation started with two scientists of the Applied Research Institute of Vilnius University introducing their baby – a solidstate illumination system with controlled and variable colour rendition properties. To put it simply, we saw the possibility of sharpening and fading colours by using a simple (to our eye) white light. Manipulating with how we see things gave the feeling of something between science and paranormal power – the perfect introduction to the logic of curating of Raimundas Malašauskas, the curator of Oo. | |

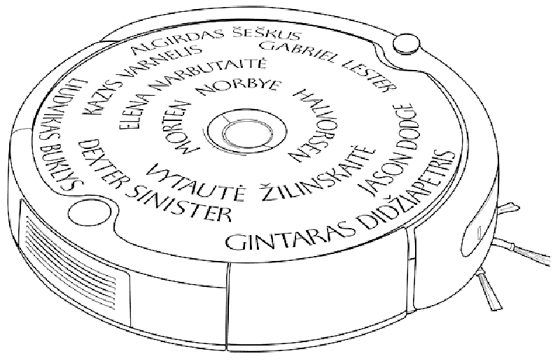

Roomba Courtesy Oo | |

| Curator Raimundas Malašauskas is the most renowned contemporary art curator and author coming from Lithuania. After 11 years working at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius, in 2007 he left and took up the position as curator at California College of the Arts in San Francisco, and later at Artists Space in New York. Most recently he worked as an agent in the dOCUMENTA (13) curatorial team. He is an events curator, as his shows usually consist of performance, hypnotic séances, holograms, ephemeral happenings and texts. Artists repre- senting different art forms, scientists and parapsychologists usually become the working agents or implementers of Malašauskas‘ scenario script. Literary fiction, parapsychology and scientific innova- tions connect on the platform of the mystery of (im)possibility, and refuel our imaginations. His ongoing project Hypnotic Show, which has toured San Francisco, New York, Paris, Amsterdam, Mexico City, Turin and Kassel, is an exhibition that an audience experiences while hypnotized. A number of invited artists submit proposals for the professional hypnotist Marcos Lutyens to perform on the audience through a session of hypnosis. It’s the ultimate experience of a text, of a description. What’s left after the show? “Reconfiguration of princi- ples about workings or art and mind implied by artists’ proposals” – answers the press release of the Hypnotic Show project – a list of an- swers to Frequently Asked Questions. Not having been hypnotized in an exhibition myself, I don‘t think I should try to come up with a better answer. Nation In the history of the Lithuanian entries in the Venice Biennale since 1999 there have been several quite successful attempts to use the Lithuanian pavilion in Venice as a tool to solve some national prob- lems. The Villa Lituania project by Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas in 2007 refuelled discussions about the interwar Lithuanian embas- sy building in Rome, which became the Embassy of the Soviet Union after the occupation of Lithuania in 1940. The ownership was not restituted after Lithuania became an independent country again in 1990, and a building once called “Villa Lituania” became the Embassy of Russia. In the Villa Lituania project, the question of Italy and Russia being ignorant about this case was addressed through different kinds of performative actions. Only in February, 2013 an agreement on compensation was reached between Italy and Lithuania. The last biennale was used as a platform for discussion about another internal problem: the lack of a cultural policy in Lithuania. Darius Mikšys’ project Behind the White Curtain attempted to bring the whole Lithuanian art scene of the past two decades to Venice for the connoisseur biennale visitor to curate, and to decide who’s worth attention and who is not. Lithuanian visual artists that have benefit- ed from state grants over the past 20 years (and that’s the vast ma- jority of all the visual artists in Lithuania) were asked to provide the project with one artwork created during the state grant period. The problem with the state grant system is that there are no clear qualita- tive measures applied when allocating the grants, and there are only quantitative reports submitted after the grant period. All the collec- tion was put behind a white curtain in the pavilion, and the biennale visitor, looking at a catalogue, would choose his/her own exhibition to be brought out from behind the curtain, especially for him/her. The project became very controversial, as it was very tempting for artists to have their works shown at the Venice Biennale, but they were left feeling used and disrespected by being merely the material for somebody else’s project. This year the question of “national” in the “national pavilion” was taken to another level. Oo is an exhibition of the national pavil- ions of two countries – Lithuania and Cyprus. No logical, or at least apparent, reason for connecting these two countries can be found. The main reason for doing so is happy coincidence. Malašauskas was asked to curate the Cyprus pavilion for the 54th Venice Biennale, but at the time he was already engaged in working on projects for dOCUMENTA. When in April, 2012, the Brusselsbased Lithuanian gallery Tulips&Roses, now managed by the pavilion commission- ers Jonas Žakaitis and Aurimė Aleksandravičiūtė, submitted the Malašauskas project to the Lithuanian pavilion competition, there were no Cyprus artists included in the project. But then in the autumn of 2012 Cyprus suggested the position of curator to Malašauskas once again, and it was agreed to present a joint exhibition. There are already a few storylines going through here, and my attempt to tie a knot can be called “rethinking the process of choosing the representative”. In Lithuania, only an institution with a three year experience of managing international projects can apply to the Venice Biennale pavilion project competition. The winner is selected by an expert board of five art specialists selected by the Ministry of Culture. In November, 2012, the dissatisfaction with this system was put down in writing for the first time in an open letter. The letter was signed by the Lithuanian Interdisciplinary Artists’ Association, an artistrun organisation established in 1994 when the Lithuanian Artists Union, a Soviet relict, didn’t seem to keep up with the chang- ing art world. The main point of the letter was that the competition now is meant for choosing an institution, and not the artwork or exhibition concept. The Estonian system was given as a good example, where the same institution – the Centre for Contemporary Arts – or- ganizes the competitions, selects the project and later on manages the laying out of the pavillion. And now, knowing the Oo story, we are getting familiar with another system – the one used in Cyprus. An Advisory Committee for the Selection of Artists and Works of the Ministry of Education and Culture, comprising a number of indepen- dent art professionals, selects the curator (not necessarily a Cypriot one, as we can see). When the framework of the exhibition is made clear by the curator, an open call for artists’ participation proposals is announced and then the curator chooses, and the commissioner is Louli Michaelidou. The Cyprus pavilion as an independent unit is being promoted quite well as “not afraid of being international”, which means opposing “national” to “international”. On the other hand, the Lithuanian pavilion is much more ephemeral in the media, and there’s more talking about the whole exhibition, already with the Cypriotinternational part, rather than distinguishing the Lithuanian pavilion and the six Lithuanian artists together with the same four international artists. It seems that “national” here is melted by, let’s say, “exhibitional”, while caring more about an abstract “anational” universe of the mind. | |

Palasport Arsenale Photo: Marco Giacomelli Publicity photos | |

| Venue Oo will take place at Palasport Giobatta Gianquinto (Palasport Arsenale), a modernist sports hall designed by Enrichetto Capuzzo and built in 1977 on a side of the historical Arsenale area. The perimeter of the Palasport site is extruded upwards by a windowless, insitu, cast concrete wall – a modernist architectural gesture towards its historic context. However, this huge structure is in a way interestingly misplaced – it seems too modern, too big, and nobody among the visitors to Venice really perceives all of its volume and its function, and only few of them use the passageways around it. On the other hand, the building is used very actively by the local community, and coordinating entry to it with an exhibition started easily, but then took plenty of effort, as every manager of the several sport schools using the sport hall had to be convinced, the exhibition will not be an obstacle for their activity. Getting to know the community and merging an exhibition with sports events was not in the plans of the organizers, but in the end it in a way moulded some parts of the exhi- bition corpus. For example, a festival of calisthenics will take place at the Palasport Arsenale in June. 120 girls (aged 4 to 12) will perform in the scenography which will form a part of the exhibition. Setting up in an “avenetian” (not gorgeous, and not classical in style and atmosphere) interior was one of few things that organizers knew they wanted for the exhibition from the very beginning. Pala sport Arsenale should give the feeling of leaving biennial Venice for a while and entering the parallel, unknown world of everyday Venice. Walls The inner space of Palasport Arsenale, its hallways and the big hall will be structured by a piece of art by Gabriel Lester. It‘s socalled Oo display architecture, which is to be constructed from modular walls shipped to Venice from a number of museums in Europe. Elena Narbutaitė, another artist of Oo, named the architecture Cousins. Only some walls will be occupied with actual works of art hanging on them – others will provide spatial experiences. They will be of dif- ferent colours and in different condition, and will play with the very idea of displaying and will work as a stage set for the sequences. Catalogue Three tales from the 1970s, by the popular Lithuanian children’s writer Vytautė Žilinskaitė, will be published in two languages as an exhibition catalogue. As artist Robertas Narkus was reading the tales, sitting at the Venclovas table lit by the illumination system with variable colour rendition properties (and the colours of Robertas changed according to changing atmosphere of the story), it became so evident that the accurateness of description in Žilinskaitė’s writing style and clashes of technology and paranormal phenomena in the stories must have been in the scope of Malašauskas a long time ago. Apparently, the minds of the organizers were made up about the catalogue quite early as well. Stories about a goat kid that jumped out of a cartoon because he got bored and then had to run away from a gang of wolves, a cactus that got wounded and then blossomed, and a talking robot that got damaged after having a few conversations with a butterfly, are at the same time very playful, dramatically charged and easily adding some paranormal sincerity to 1970s normality. Even though the tales are from 40 years ago and the scenes seem to be based in a very contemporary scenography, the stories create an impression of atemporality, or at least parallel timing, as a good tale is supposed to do. Reading the tales in the Palasport Arse- nale which was built in the 70s at the same time connects you to the already nostalgic modernist space, and takes you away to the atemporal space of the exhibition. Concept When asked to explain the concept, Malašauskas uses the term “se- quencer” which can be understood as an exhibition construction model, rather than a concept. The term is used most often in music and computer engineering or microbiology as a tool for making automatic sequences of a drum beat, addresses or DNA readouts. In the discourse of curating it stands as a (semi)automatic tool for creating different mental and physical pathways for the exhibition visitors. “Concepts are made there, or discarded subsequently”, claims the curator. A sequencer generates orders of bodies and clots of knowledge, depending on the circumstances it encounters. These circumstances are in transit, in the same way the contents of the exhibition becomes the same. Malašauskas‘ project Repetition Island which took place in the Centre Pompidou in July, 2010, was an ultimate exploration of perceiving a sequence depending on the circumstances. For a week, a daily scenario of successive and overlapping conferences, screenings, performances, lectures, concerts given by artists was repeated every day as if doing exercises, and having a chance to perform them differently (better is too strong a word, I suppose,) every time. No repetition is planned for Oo, as far as I know, but a longue durée experience for visitors is still an aim of the organizers. Even though all the concepts are left to form themselves, there is still a framework for a sequencer to begin its work. Fatal points in life which seem nonconceptual at first glance, all the beginnings and the endings, but also those periods during which you train your- self for something that you plan to happen – these are the energeti- cally charged knots that hold at least some of the stories together. This interest in fatal events and fatal coincidences is exposed nicely in the press release, where a fatality timeline was put together. For example, it says that on 8 November, 2012, Raimundas Malašauskas landed in Nicosia to test the possibility of two national pavilions as one exhibition called Oo. Stelios Votsis, one of the most revered and groundbreaking artists in Cyprus, died the next morning. This one is the most directly fatal, and the others are more conceptually fatal, like the atmospheric one of 1 April, 2013, when according to Cyprus based Greek photographer Thodoris Tzalavras the atmosphere in Nicosia, the capital of Cyprus, was so saturated by Saharan dust that it was possible to shoot the sun with a C8+ telescope without a solar filter. On the same, day Liudvikas Buklys went to Prienai (Lithuania) to film the biggest snowman in Lithuania. The air filled with dust and with frozen water – the best things to look at and start thinking what‘s behind it all. | |

Palasport Arsenale Photo: Marco Giacomelli Publicity photos | |

| Artists It would be a spoiler if, with a month still left till the opening, you would get to know what the artworks will look and perform like, co-missioner Jonas Žakaitis says. The list of the main artists is known: Liudvikas Buklys, Gintaras Didžiapetris, Jason Dodge, Lia Haraki, Maria Hassabi, Phanos Kyriacou, Myriam Lefkowitz, Gabriel Lester, Elena Narbutaitė, Morten Norbye Halvorsen, Algirdas Šeškus, Dexter Sinister, Constantinos Taliotis, Kazys Varnelis, Natalie Yiaxi and Vytautė Žilinskaitė. Some of the works of the beginning can be seen on the websites of the pavilions at Oo-Oo.co (Lithuania) and Oo-Oo.bo (Cyprus), there you can find Antanas Gerlikas‘ dream that carried the compressed version of the Lithuania pavillion, or an interview with Darius Mikšys. Most of the works and events that we‘ll experience in Oo are being created for Oo and will be sequenced and perceived there. But a few of them happened even before there was any idea about the exhibition. Two of those are the photography series of famous Lithuanian photographer Algirdas Šeškus and a painting The Last Shot (2007 2008) by Lithuanian émigré artist Kazys Varnelis. Šeškus‘ photography series, taken in 1983, has a direct thematical connection to the Oo venue function – the photographs are shots of gymnastic exercises performed on the morning programme of Soviet Lithuanian TV. Šeškus has also another spot in the Oo sequencer – in the mid1990s he gave up photography and concentrated on his bioenergetics healing practice. Meanwhile, The Last Shot by Varnelis was his conscious decision to quit painting,, but in this case one form of energy didn‘t convert into another, as Varnelis died in 2010. As I have written about something that I hasn’t happened yet, I can only try to say what it‘s trying to escape, and that something is going to happen. That means that it‘s going to be anational, avenetian, atemporal training and accumulating of energy for something that might happen. | |

| go back | |