|

|

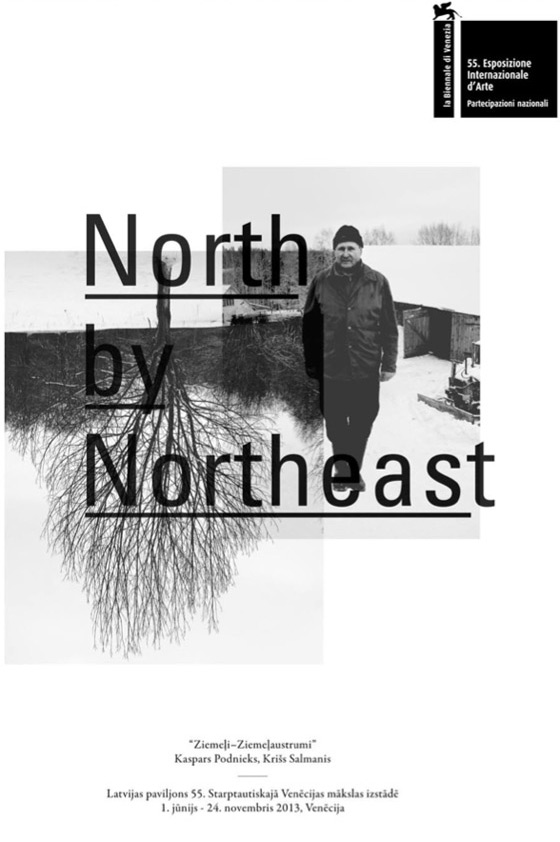

| The new Masters of the Land or our muddy pastalas* on the parquet floor of Cosmopolitan Venice Alise Tīfentāle, Art Historian Latvia’s exposition North by Northeast at the 55th International Art Exhibition of Venice Biennale 31.05.–24.11.2013. | |

| |

| These lines about Latvia’s exposition at the Venice 55th International Art Exhibition are being written in April, 2013 – at a time when the art works are still being created, art that visitors to the biennale will have already seen when this magazine is pub- lished. By the time you read this article, the reflections, doubts and worries of April will have already become anachronisms. At the same time, a look back at the process, when the result has already materialized, can assist in the analysis and evaluation of the result. The main question to which we should seek answers on reading this article is – whether the exposition North by North- east currently still being created by artists Kaspars Podnieks and Krišs Salmanis could, after its unveiling, be considered a significant turning point in the history of Latvian art and art cri- tique? Has this exposition opened up new opportunities for pro- fessional development for both artists? Have the discussions at local and international level about this exposition provided a significant contribution to the advancement of our local theo- retical discourse? Has it encouraged new creative and theoreti- cal processes, qualitative changes or advancement in the views and understanding by Latvian artists and theorists about our pos- sibilities, limits, hurdles and challenges in today’s globalized art world? This article provides a partial insight into the process of formation of the exposition, during which the questions above were formulated. The importance of (good) relationships For the first time ever, Latvia’s exposition at the Venice Biennale is being managed by an international team – the project is being organized by the kim? Contemporary Art Centre from Riga and the organization Art in General from New York. I’ve been invited to participate in the project as one of the exposition’s co-curators together with Anne Barlow and Courtenay Finn from Art in Gen- eral. National expositions at the Venice Biennale often develop as the result of international collaboration (for example, this year’s Estonian pavilion is being created by Polish-born curator Adam Budak). One could ask – why is it so important? What are the advantages in bringing in curators from other countries? One of the chief aspects is connected to the fact that a small country’s art world is small and self-sufficient, cut off within its own structure. But outside of the borders of this metaphoric vil- lage, nobody has any idea which artists are the favourites of the local critics and curators and why. The reasons why certain works are valued highly among the local circle of professionals are not always necessarily obvious to the viewer from elsewhere. There- fore there’s a risk that an international audience will not always be able to fully appreciate the things that “everyone likes” in Latvia. This is one of the reasons why collaboration with foreign specialists is so important – the curator from the outside is able to stand apart and concentrate their attention on the works, not the personalities, and make decisions which are compatible with the current demands of the globalized art world as it is at the moment. In this case, Barlow and Finn are undertaking one of the most responsible tasks in the whole process – choosing the artists for the exposition. Responding to the question posed by Līga Marcinkeviča, editor-in chief of Studija, whether this phenomenon – foreign curators, (non)national expositions – isn’t a kind of speculative reality, and what is it that the viewer and art gains from this, I should, first of all, add that the Venice Biennale as well as count- less other international biennials, triennials, quadrennials and other art festivals are great examples of a “speculative reality” – Baudrillard’s simulacrum’s simulacrum, the product of the “cul- ture industry” held in contempt by Adorno and Horkheimer, the same as the annual “carnival” in Bayreuth and other opera fes- tivals, theatre, cinema and all the other art festivals which could be looked upon as “speculative reality”. Although a critical view is needed and useful, it should be remembered that this is the dominant model of how the art world functions. In the context of visual art today, the Venice Biennale is one of the central events, a profound demonstration lesson in speculative reality, and, in taking part in it, one has to accept the rules of the game. Secondly, international collaboration is a wonderful oppor- tunity for dialogue, and those who gain are both the viewers as well as the artists. In its own way a monologue is the easiest form of communication – an authoritative voice which says “how it all is”. A dialogue, in contrast, is a process which leaves room for opposition, or at least different opinions, a variety of views and experiences. Dialogue of its own is not and cannot be an end in itself. However, I believe that, as opposed to monologue, a dialogue is a more productive discussion model, as something new can come out of it, the sum or compromise of differing ideas from the participants involved. The formation process of the North by Northeast exposi- tion is to a large degree organized just like this – like a collective product based on relationships and dialogue. The curators – Barlow, Finn, and the author of this article – don’t interfere with the artists’ creative process, but concentrate on maintaining a dis- cussion with the viewer, making sure that the viewer has all the necessary instruments for a satisfactory conception and under- standing of the exhibited works. Each work – Krišs Salmanis’ North by Northeast and Kaspars Podnieks’ Rommel’s Dairy – maintains its autonomy in the exposition, too, reflecting each author’s individual intention, but at the same time offering the possibility of a meaningful mutual dialogue. How does such a model function? The process is based on relationships between people, between people and works of art, and between the artworks themselves. Moreover, I should add that Nicholas Bourriaud and “Relational Aesthetics” are not be- ing invoked here in any way. Podnieks and Salmanis create fin- ished, complete works of art – objects, instead of creating a more or less believable illusion about social interaction like the artists mentioned by Bourriaud. In these relationships, the curators have a significant role. Barlow and Finn organized a lead-in exhibition for the biennale at the Art in General gallery in New York (North by Northeast, 5–30 March, 2013) in collaboration with kim?. The opening of the exhibition was planned for the SoHo Night during Armory Arts Week. This exhibition was a valuable investment in the overall process of creation for the biennale exposition. The exhibition revealed what a viewer that is new to Latvian contemporary art sees in it, one who doesn’t know the artists, knows nothing about the Latvian art world or its history, traditions and hierarchy. There was also a public lecture (4 May, 2013) organized by Art in General, in which the author of this ar- ticle was entrusted to introduce, to those interested, the concept of the North by Northeast exposition, to talk about Podnieks’ and Salmanis’ creative activities and to provide an insight into the context of Latvian art history. Similar discussions will also be continued in Venice as well. One may well ask why the partners for the collaboration were chosen specifically from New York, conversely, one could respond to that with another question: but where else? Even though the contemporary art world is glo- balized and cosmopolitan, New York still continues to be one of the most important centres, at least in the Western world. What is the goal of these kinds of relationships? Similarly as between two people – whether it is friendship, love or collegial relationships – the main thing is discussion, and a good discus- sion is one which is “about me”. The creation of the exposition, as well as the exposition itself is this type of discussion. Works of art will definitely be at the centre of attention in Venice, but currently we’re in the middle of a discussion – the discussion is ongoing onsite in Riga and in New York, and remotely through countless e-mails which are being exchanged by everyone in- volved, in Skype conversations, telephone calls and text mes- sages. In an ideal situation, the exposition will stimulate discus- sions between viewers, both about what is significant about Podnieks and Salmanis as artists, as well as in the wider sense – what is significant in Latvian art. A conversaton in pastalas on a parquet floor Another no less significant question – what is our discussion about, then? My view is that the nascent biennale exposition, to a large degree, is a discussion about us – about contemporary Latvia – and about our art, and everything is being done so that the biennale’s international audience is included in this discus- sion which is so important to us. North by Northeast is contemporary and at the same time very Latvian art which is based on Latvia’s culture and art traditions. Podnieks and Salmanis, using current and cosmopolitan means of expression in contemporary art, are promoting a discussion about the Latvian countryside, about the land and work. Memories of childhood in the countryside and “one’s own” country, which almost everyone has, even the most urbanized Riga resident, is something very specifically Latvian. Such a strong connection with the earth and the countryside disappeared from many places in Europe long ago, while in America the concept in this sense has never existed. For the viewer who is familiar with the Western art canon, Salmanis’s work could invite distant associations with the art language that was established by the Arte Povera artists in post war Italy, especially Giuseppe Penone and Jannis Kunellis, who often selected rough, unfinished and uncivilized elements from nature for their art materials. The influence of Robert Smithson is present. Podnieks’ photographs, in turn, could remind one of, for example, Richard Long’s time-consuming and labour inten- sive performance documentation, as well as the artistic practices of famous 20th century photographic artists like Jeff Wall, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Gregory Crewdson and others creating constructed and multi-layered landscapes. Yet the possible analogies are distant – with an awareness of this, it is sufficient for a critical mind nurtured on the Western art canon to recognize the means of expression and visual strat- egies of generally accepted contemporary art in the works by Podnieks and Salmanis. Much more important is that part of the discussion which relates to the historical traditions of Latvian art and its continuation in the creative work of both artists. I believe that in this context it’s possible to draw the straightest line from Vilhelms Purvītis and Janis Rozentāls to Krišs Salmanis and Kas- pars Podnieks, furthermore without any provocative or heretical undertone. Nobody is trying to threaten or diminish the respect and value of the classics through this statement, overconfidently mentioning them in the same sentence with our contemporaries, of whose probable contribution and significance to Latvian art history no-one, as yet, has any idea. This line is a powerful and persistent vector of development in Latvian art, assigning a unified and meaningful progression to seemingly incomparable phenomena. By “national tradition”, in this case, we understand a live and contemporary progression of creative exploration – the tradition itself in its development, not the following of tradition, the imitation of examples or attempts to emulate the achieve- ments of masters of previous generations. It keeps up with the times as an idea which each generation of artists finds and ex- presses anew. Paraphrasing art historian Aleksis Osmanis, one can say that this straight and shining vector is national tradition, which is no longer “something impolitely provincial, like muddy pastalas on the parquet floor of cosmopolitanism”(1). Even though the artists really are heading for Venice in muddy pastalas in the literal sense – the creation of both Podnieks’ as well as Salmanis’ objects require the investment of a huge amount of rural work – it is these pastalas specifically, as an element of the “national tradition”, which makes our discussion interesting to others. A verbal discussion about “national tra- dition” in contemporary art risks balancing on a knife-edge be- tween primitive sentimentality and pathos-filled attempts to bring Edvarts Virza’s [literary work] Straumēni to life in the 21st century. It is possible to get closer to an understanding of this idea in a less risky way through works of art. One could say that the line of development which is expressed in the North by North- east exhibition can also be encountered in such works as Janis Rozentāls’ No baznīcas (‘After Church’, 1894), Vilhelms Purvītis’ “Pavasara ūdeņi (Maestoso)” (‘Spring Waters (Maestoso)’, 1910), Teodors Zaļkalns’ Māmiņa (‘Dear Mother’, 1915), Kārlis Mies- nieks’ Dienišķā maize (‘Daily Bread’, 1929), Edgars Iltners’ Zemes saimnieki (‘Masters of the Land’, 1960), in Inta Ruka’s series Mani lauku ļaudis (‘My Country Folk’, 1983–1998), Ieva Auziņa’s and Estere Polaka’s project Piens (‘Milk’, 2004) and in many other examples of Latvian professional art. “Where are we going?” Paul Gauguin once asked rhetori- cally, and the direction may not always be obvious. It is, how- ever, completely clear “where we have come from”, and an un- derstanding and reflection about our roots makes art valuable and interesting to an outside viewer also. For example, Ģederts Eliass, a classic of Latvian painting who, as has been accurately deduced by art historian Laima Slava, mastered the most avant- garde artistic means of expression of his era, worked in Paris, Brussels, Florence and elsewhere, and rendered his world-class unique contribution with “a story on an epic scale about the Latvian homestead”, about the Zīlēni(2) where he was born. Smithson, Wall and the others are not far removed, but the discussion which Podnieks and Salmanis are continuing in Venice this year is about Latvia. Translation into English: Uldis Brūns * pastalas are a simple form of traditional Latvian footwear made from a single piece of leather. 1 A fragment from Aleksis Osmanis’ article about artist Edgars Iltners is cited: “And he painted at a time when national tradition wasn’t yet something impolitely provincial like muddy pastalas on the parquet of cosmopolitanism, when concepts like “aesthetic”, “beautiful”, “good” and, the main thing, “Latvian painting” still existed.” – Osmanis, Aleksis. Socreālisms kā tēma. [Socialist Realism as a Theme] Studija, 2007, No. 5, p. 25 2 Slava, Laima. Ģederta Eliasa mīklu minot. [Solving the Riddle of Ģederts Eliass] Book: Ģederts Eliass. Ed. Laima Slava. Rīga: Neputns, 2012, p. 10. | |

| go back | |