|

|

| Visions, phantoms and poetic schemes Santa Mičule, Art Academy of Latvia Artūrs Virtmanis. (10 000) Melancholy Folds 09.11.–09.12.2012. Rīga Art Space, Intro Hall | |

| The first solo exhibition of artist Arturs Virtmanis (born 1971) in Latvia has enjoyed quite considerable attention of the mass media and the public, boosted by such PR taglines as “has lived in New York for 16 years”, “has worked on the stage design of the most expensive Broadway show”, etc. which were flaunted every time the exhibition or the author was mentioned. However, on viewing (10 000) Melancholy Folds more in depth, the showiness created by such catchy phrases turned out to be superfluous and was forgotten, as it did not correspond to the contemplative mood of the works displayed at all and was in contradiction with the author’s reaching towards superhuman levels of existance. The exhibition (10 000) Melancholy Folds was presented as a spatially and metaphorically dense installation where the drawings, assemblages and sculptural objects were hiding rather than revealing approximately 10, 000 facets of melancholy. They are, of course, evi dent not only in Virtmanis’ exhibition – if we speak about melancholy as an aesthetic phenomenon, we must note its unusual presence in the culture of Western Europe throughout all its stages. It is the his torical dimension that reveals the multifacetedness of the concept of melancholy. For the ancient Greeks, for example, melancholy was a certain temperament type, characterized by spirituality and reason, moreover Aristotle declared that melancholy was the temperament of great and distinguished personalities. Medieval scholasticism at tributed melancholy with sinfulness, and it was later redeemed by NeoPlatonists, who reanimated melancholy as a characteristic trait of the modern genius and a state of intellectual creativity. Immanuel Kant also thought that melancholy was connected with the beautiful and the sublime. Melancholy found its expression in the court culture of Elizabeth I in England, where it took on a religiously existential slant, but in French Rococo culture, on the other hand, it had a more sentimentally frivolous character. In the age of Romanticism, elegiac melancholy as the expression of intensest poetic feelings became the most popular emotional tonality. The art of the 20th century, how ever, was dominated by destructive feelings of anxiety and absurdity, which preserved the contemplative character of melancholy. On the other hand, the culture of postmodernism brings us to the diagnosis of society presented by Jean Baudrillard, where he announces that melancholy is the fundamental passion of the modern person and a trait that characterizes the disappearance of meaning. This small culturalhistorical introduction was necessary in order to distance ourselves from the simplified notion that we normally associate with melancholy and to approach the issues that inspired Arturs Virtmanis to create the exhibition. The exhibition could be interpreted as the author’s personal version of the modern notion of melancholy, based on the motives of fragility, impossibil ity and entropy which permeate both the formal construction of the objects as well as the overall message of the works. The artist was inspired by the famous etching of Albrecht Dürer, Melancholia I, and the exhibition was shaped as a transfer of Dürer’s etching in time and space, rephrasing the images and symbols from iconography of the 16th century. For example, the building instruments were replaced by instruments of destruction (a saw, a scythe). Dürer’s mysterious etching has been important in the creation of the exhibition, but it has been incorporated in the visual structure creatively enough so as not to leave an impression of being a tasteless mechanical copy. Even though the annotation issues a warning that without knowledge of the artist’s vocabulary it is possible to interpret the exhibition incor rectly, the objects exhibited seemed to be artistically selfcontained and attractive, even without knowing the meanings encoded by Virtmanis or Dürer. | |

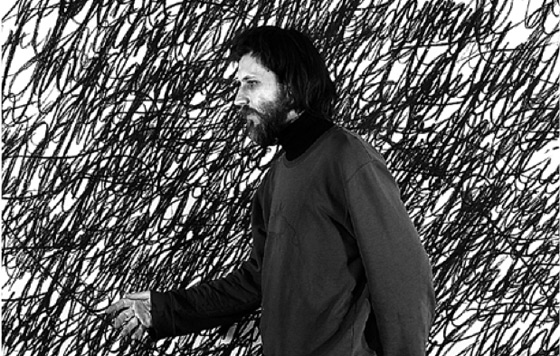

Artūrs Virtmanis. 2012 Publicity photo Courtesy of the artist | |

| The materials used (cardboard, paper, scotch tape, charcoal) are pronouncedly democratic and the sketchiness of the forms may seem to be secondary or unintentional, but only for the first moment. The mutual contrasts in scale and use of material, and the free organizational structure utilized in the space, created an unreal effect of inversion which in the artist’s own vocabulary has acquired the description of impossibility. Virtmanis’ melancholy is impossibility and art is a way of making possible that which is impossible, at least briefly. The notion of impossibility is to a large extent that which un ravels and unites the many aspects of melancholy, it embodies the utopian state of artistic freedom and fantasy whose fragility and tran sience (the paper tape is about to disintegrate...) is a source of mel ancholy. Thinking in the framework of binary opposites, melancholy in Virtmanis’ exhibition functioned as an overarching metaphor for everything that does not fit into the superficial mythology of positiv ism; it is a natural byproduct of every deeper observation of the sur rounding exterior and inner world, and attempts to understand the essence of existing things and how they are interconnected. To a large extent the exhibition took place outside the borders of physical space, in other words – in the minds of the viewers. The material objects served as road signs of melancholy in an ironic play upon images that to the viewer were easily recognizable and elicited concrete associations. Inherent in the notion of entropy is not only the process of disintegration, but also the story of how things were before the process started. The poetic passages conjured up by Virt manis are exhilarating and strangely familiar, but they are difficult to retell as concrete thoughts or events. Thinking about the emotional mood of the exhibition, alongside the metaphors of the artist’s favou rite author Pessoa, more Northern associations also come to mind – for example, the state of the soul as described in Hermann Hesse’s ‘Steppenwolf ’: “And when a man is sad – I don’t mean because he has a toothache or has lost some money, but because he sees, for once in a way, how it all is with life and everything, and is sad in earnest – he always looks a little like an animal. He looks not only sad, but more right and more beautiful than usual.” The high density of references and metaphors with their many layers of meaning have in a way made the exhibition unapproach able, especially for those viewers who are interested in unequivocal explanations, concrete questions and answers. Even though the exhi bition notes did not function as an explanatory guide, this should not be perceived as a drawback, rather an invitation to independently study the constructions made by the artist and for ourselves to be come a part of that invisible side that for Arturs Virtmanis is a crucial constituent part of art (and the world). Santa Mičule: How important in your creative life is this first solo exhibition in Latvia? How do you feel being at the centre of attention of the local art scene? Arturs Virtmanis: It feels great. I am not so sure about that centre and abundance of attention. It’s pleasant, but I’m trying stay circumspect and not to focus on it too much, I don’t want to sud denly start feeling terribly important. But it’s a nice feeling, because it’s much more pleasant to show your work here than in New York, where there are so many exhibitions taking place simultaneously, and you cannot possibly draw attention to what you’re doing be cause all the attention goes to those ten superstars who are basking in the limelight at the top. It’s more fulfilling to exhibit here, people do attend, and there is a deeper meaning in that. I’d been wanting to organize an exhibition a while back already, but it didn’t happen because of the logistics, and time, and money... and there are always many things to do, because it takes up quite a lot of time to prepare such a comprehensive exhibition. All in all, I’m happy to exhibit my work here. S.M.: You have mentioned that one of the things that moti- vated you to move to New York was the fact that when you gradu- ated from the art academy, you didn’t feel that you’d matured yet as an artist. What processes and impulses have influenced your growth and formation as an artist? A.V.: To a great extent life itself, mingling with others, seeing and hearing different things, learning in a nonacademic way. I didn’t go there to study, I went to wander the world like a Sprīdītis1. I went there to go to museums, to read and listen. In a way it was a more ac tive process of learning than at the academy – there we had sculpting and drawing, all of that was easy to understand and I was good at it, but the intellectual part was lacking, I wanted a different informa tional space where there might be something incomprehensible. I am interested in things that I don’t understand, in art as well, other wise there is no intrigue. It’s not a given that the physical place where you are determines everything, it does determine something, but I doubt that it governs the essential part. I think that the primary thing is our inner impulse. A place can only encourage or impede certain ways of expression. S.M.: Your age places you among that generation of Latvian artists who came onto the scene in the mid1990s with provoca- tive and ironic works, with ideas that screamed individuality. Do you feel any kinship with these artists, any parallels with their artistic thinking and working? A.V.: I do feel it, but not literally, because at that time I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do, and those we are speaking about, Fišers, Gabrāns and others – they started very convincingly. But I didn’t feel that way about my work. In that sense I am much younger than they are, I was a child at that time. You come out of the academy and you don’t know what to do. But I was also greatly influenced by the Latvian artists of the generation before me. I feel very close to Oļegs Tillbergs, in my opinion, he’s one of the mightiest artists we have. His works with all those sports cars on oil paper, pneumatic hammers, and gels was the first impulse that made me understand: wow, look what you can do with art! S.M: To what extent do you follow what’s happening on the Latvian art scene? What impressions have you gained about what is happening there right now? A.V.: My impressions must be quite deformed, because I only fol low certain artists whom I know personally, not the whole Latvian art scene. I can’t say that I am aware of all the nuances of Latvian art. For example, I follow my good friend Romās Korovins, Miķelis Fišers, Gabrāns, Bikše. I like Maija Kurševa, Arturs Bērziņš. Following a few artists, the impressions are good, following the entire art scene – maybe not so good. (Laughter). There is a shortage of liveliness, deep er study; there are many impersonal works, they are as if modern but they are boring to look at. They are clichéd, the attempts to make them contemporary in terms of technique are evident, but when you see thousands of the same kinds of things over several years, when you start to notice similarities and strategies, your perception grows dull, on the one hand, but on the other hand – in the mass of works you start seeing types, not individual works; they don’t speak to you but simply become a fact. That is not a reproach to Latvian artists, but I do think that there are too few deep, wellconsidered, suc cinct, surprising works. Though there’s few of those in the rest of the world, too. We know that there isn’t that much good art that speaks to both your mind and soul (if we believe in such a thing). S.M.: And how do you regard your own works according to your own criteria? A.V.: Everyone has illusions about themselves. We each of us are enslaved and indebted to our being. In my art I try to do the thing that, scratching away over many years, I have come to understand as being truly my thing, that which is authentic to me, not thinking about outcome. We know that there was a clearly defined pathway during the Soviet times, and there is one also now. It may not be as well de fined, but we can feel it – we know what is in vogue, what’s pleasant, what’s easy on the media, what’s easy to talk about... there is a cer tain quality of poppiness to it... It’s hard, in this flood of mainstream, to set aside and find that which is deeply yours, not thinking about what it’s going to look like or how you are going to sell it. What I like about working with paper – the models are not subject to easy clas sification, they are not easy to stuff into a standardized model. S.M.: So good art is that which is harder to define and classify? A.V.: Yes, yes. Incomprehensible, difficult to perceive art, that is hard to sell. That’s the difference between design and pop art... or if we were to compare it to food, the easier it goes down, the better it is. In my opinion, in art it should be different. I think that the bite of art should get stuck in your throat, you have to cough and then maybe it works. Otherwise it’s like water to a duck – oh, it’s pleasant, but nothing more. S.M.: Art mustn't be comfortable... A.V.: For example, I like Matisse, who said that art must be like an armchair, but it seems like people have taken this too seriously. What Matisse said was a reaction to the external circumstances of the time, it was a compensation mechanism during wartime. Now it’s the opposite: we have so many armchairs that it would do us good to sit on shards of glass for a while. I’m not speaking about aggressive ness or scandalous art; I dislike aggression and scandalous art too is insipid, it plays out one speculative trick and beneath the surface there’s disappointment. | |

Artūrs Virtmanis. (10 000) Melancholy Folds. Installation. Fragment. 2012 Publicity photo Courtesy of the artist | |

| S.M.: You don’t consider yourself to be an artist with a socio political agenda, do you? For example, many of the immigrants from the East, from Islamic countries, create works focussing on the problems of their ethnic homeland, thus attracting a lot of attention from the public. Are you not interested in the actual realities of Eastern Europe? A.V.: I’m interested in it insofar as I myself come from that part of the world. I’m interested in understanding our dark side, not so much the social aspects. If we take that vessel of art and fill it with content, it might overflow at one point, and in my case the socio political aspects might spill by chance, but that’s not the main direc tion of my art, the axis around which it all turns. If someone wants to work with political issues, they should go into politics, it’s much more effective. I am a hermit in this sense. S.M.: I recall the recent performance in a church by the Rus- sian punk rock group Pussy Riot the political uproar that it stirred up was far greater then any outwardly political "moves". A.V.: With regard to Pussy Riot the question is: how much of it is art? It’s activism that uses artistic means of expression, true, but I doubt that it’s art. I like what they did, because it’s something deeper: their performance in church was a nondogmatic prayer, they were praying to God – get rid of that Putin! The way they did it was very artistic, but it doesn’t mean that it’s art. In that sense I am purist. There is activism, you can do it very creatively, but it doesn’t mean that it’s art. S.M.: One of the most widespread points of departure lately in artistic creativity is art as research. That is, artists assume the role of “researcher” and present their achievements as artistic research, thus risking that the artworks will be stripped down to formal pseudoscience. Your works, on the other hand, seem to be natural and personal, indicating that for you art is not re- search, but rather a process of selftherapy. A.V.: I cannot completely isolate myself from research which, of course, isn’t research in a scientific sense. I’ve often thought that art is about what we are able to imagine. It’s like a visible outer boundary of our physical perception, our thoughts – in that sense it is research. An artist is like an Argonaut who goes to the end of the world and brings back a report of what he has seen. This isn’t transmitted in a rational way, although there is a lot of rationality in it, but I’m interested in poeticism. That’s why I call my works poetical schemes: because they are very structural. I’m interested in impos sible spaces, everything that’s to do with imagination and fantasy. At the same time it is not the classical surreal dream business, those dream things are very fluid and formless. In my works there’s also a lot of structure, mental structures, that’s why it’s appropriate to call them schemes. Poetry, too, can be viewed schematically and we can understand how it’s been built. The scheme cannot replace art, and it can’t take the priority in art, but it will always be present. S.M.: When putting together this exhibition you were influ- enced by Albrecht Dürer’s etching Melancholia I. One of the most popular interpretations of this work is that it is Dürer’s spiritual selfportrait. Any work of art could be interpreted as a spiritual selfportrait of its creator, but how much of that is true with re- gard to the exhibition (10 000) Melancholy Folds? Where do these images and structures come from? A.V.: The images are quite internal, there are very few outside influences. It is my world. But with Dürer I liked that mystery, for example, about the prism, which I tried to transfer to our time as a disco ball. The etching I used as the structure, as a point of support. Remake – Melancholia II. (Laughter) S.M.: Many images and forms recur in your works on a regular basis. Do you like returning to certain motives? A.V.: It’s partly because I like emphasizing the relativity of scale. Scale influences us, it’s like a game that our consciousness plays with the way we perceive things. For example, there are very small ob jects that we might see as something very large in childhood. There is something unreachable in that smallness, I like playing with it and that’s why the objects recur. On the other hand, how many of those images are there? At the exhibition we see those objects thrown in a heap on the floor, but at the same time they are very refined forms which I have worked on a lot. It’s simply that I don’t try to place em phasis on the formal aspects. We could disassemble these complex schemes and place each object on its own pedestal – it would be a completely different image, a different scene; we would have given each work a higher value, but the feeling of a common, integrated world would be gone. S.M.: As a sculptor, what is your relationship with the material? A.V.: There are all kinds of things that I like, but when I’m creat ing my things I’m interested in the nonmaterial part. That’s why I work with paper and cardboard models – they are like projections of the conscious which never weigh you down with their materiality. The works are more like mental constructs, like apparitions. We can’t call them ghosts, they are more like phantoms... That’s when the the atricality comes out. We know how stage props are built: on stage they are not the actual things, they only describe something, they point to materiality but don’t overwhelm with their materiality. That cardboard has absolutely no monetary value, but in some strange way it’s aesthetically very enjoyable. That’s the game – cardboard is packing material, it’s been created to hold something. In this case, cardboard is packaging material for certain meanings, it holds them, the material describes their shapes in the space. In that sense it’s a complete vision, a dematerialized sculpture. | |

Artūrs Virtmanis. (10 000) Melancholy Folds. Installation. Fragment. 2012 Publicity photo Courtesy of the artist | |

| S.M.: It’s just occurred to me – the use of fragile materials indirectly indicates that entropy occurs only with the fragile and the weak. A.V.: No, I think that entropy impinges on totally everything, it’s just a matter of time. We look at the Egyptian pyramids which were built for eternity – and they are already partly in ruin. We see them as beautiful objects that have suffered the ravages of time, but in reality they are manifestations of entropy. Sand, and the mud under your feet will be the most lasting elements, these won’t change their form, all else will turn into mud. The papers [in the exhibition] point to the fragility of the world. S.M.: Have you thought about what your ideal viewer would be like? What perception or approach is the most appropriate in order to understand your works and really get into them? If it’s at all important for you to be understood. A.V.: It’s not very, very important to me, but I think that it’s nice for anyone if people try to go in depth and understand. My ideal view er would have read Fernando Pessoa, Pablo Neruda, he/she would have visited the Paris Navigation Museum, would have looked at sub marines and old time scuba equipment, they would have travelled to the North Pole and felt a great void. They would have listened to Glen Gould playing Bach, thay’d be a listener of Gould’s documentary se ries The Solitude Trilogy made for Canadian radio about people who have deserted civilization and live far in the North, and would have seen Béla Tarr’s [Hungarian director] films. S.M.: Therefore your ideal viewer and you should have cer- tain aesthetic and cultural experiences in common? A.V.: Well, yes and no. It was sort of a joke, but I do like it when people have their own interpretation, that they are not afraid to look and see something of their own, they are not demanding an expla nation. I like it when artworks function as machines that produce interpretations, where the viewer creates their own worlds in inter action with the artwork. I don’t have access to any sort of final and official explanation of my works, I too only interpret them. I can tell you what I’d been thinking while I was creating the works, but that doesn’t mean that the meaning of the works is locked in my interpre tation. Sometimes I don’t even know what the works are about, and often it doesn’t even interest me. There is just a feeling that I have to keep on pursuing. When we are groping in the dark and we feel some shapes – maybe we recognize them, and maybe we don’t, maybe we know the meaning, and maybe we don’t. And maybe the unknown forms are even more beautiful and more impressive than the ones we are familiar with. S.M.: Do you separate art that you create for exhibitions from the art you are commissioned to do for stage designs? A.V.: I try not to, but it does happen. There are other tasks and other methods; in that sense I do separate them. If this exhibition were stage design, it would be for a nonexistent play: there is no story and no actors. In theatre we work with literary material, the director’s idea, music; that is design and this is art, there is a cer tain difference. It doesn’t mean that one is more interestin S.M.: What exactly interests you in scenography, what is the direction you are working in? Do you retain the essential core that weaves through your socalled exhibition art? A.V.: I think that it’s impossible to run away from yourself, we are only able to think what we think. Stage design is an area where it’s possible to mix various things fairly freely, because there is never any claim of instrinsic artistic value: for example, an object on stage would never be considered a sculpture. The objects in scenography are there insofar as they are mixed up with the story. In that sense you can work quite freely with our extensive cultural heritage. The atre and opera performances often carry a huge amount of baggage. It’s interesting to me, for instance, to play with traditional interpreta tions, etc. There I create a model for the stage design, and here also I create small shapes reminiscent of models. That’s all similar. Creat ing a model is the most beautiful and interesting part of scenography, because reality (money, technical means) defaces everything, ruins the created ideal world which can only exist in a small box. As far as I’m concerned, there could well be no next step, I would happily stay in the world of models. S.M.: Andris Breže recently said something similar. When asked why he hadn’t held an exhibition for such a long time, he said that he had already answered all the nagging questions in his head and could easily do without an exhibition as a physical manifestation of that. A.V.: I’m not so radical about it. I’m not so stylish, I still have a weakness for making things by hand, messing about and creating conglomerates, but maybe with time... You know, in life you have a certain amount of time and the question is how you are going to spend it. You can spend it by thinking a lot, but in a way thoughts are frivolous, you can imagine anything you like: it’s at the same time beautiful, but also superficial and aimless. As soon as we try to direct a thought in a certain direction, various questions arise, problems that you want to solve – that’s the interesting part. I actually don’t know if ideas themselves are that interesting. It’s interesting how you deal with ideas, just that exact moment, not the end result of the idea itself. An idea is like an impulse. It’s like with grain – each of them has a certain shape and you can sow 10 very different grains in the soil, but each of them will grow into a different plant. There is also the question of how that potential of the idea will be used. Well, anyway, that’s...commenting on Latvian classics. S.M.: Returning to scenography – do you have an ideal play in mind that you would like to do stage design for? A.V.: That’s an interesting question, I’ve thought about it, but I’ve never come to a conclusion. Actually, I have a weakness for an tique rag or travelling circus sets. In general I like simple things, even though I often have to work with highly technological plays. In real ity, the more technologies there are, the more I’m interested in sim ple things; I think they are very effective. The best shows I’ve seen have been staged in a “black box” with very symbolic sets. That’s the paradox: stage sets are far from being the main thing in the theatre! But as for your question about the play, I don’t know, actually I would like to try my hand out at directing. I would like to stage Kafka’s The Castle – I like that this work doesn’t end with anything, it doesn’t lead anywhere. Translator into English: Vita Limanoviča 1 Translator ́s note: Sprīdītis is Latvian fairy tale character (from a play written by Anna Brigadere) who set out to explore the world. | |

| go back | |