|

|

| The energetic line of Voldemārs Johansons Laine Kristberga, Screen Media and Art Historian Voldemārs Johansons. Attractors 19.12.2012.–27.01.2013. Latvian National Museum of Art exhibition hall Arsenāls creative workshop | |

| Voldemārs Johansons’ exhibition Attractors reveals a structural, systemic and mathematical perspective on art that, according to the selected methodology, corresponds to the definition “scientific research in art”. In order to study the formation of shapes and patterns as a result of natural processes, Johansons has collaborated with specialists from other fields – natural scientists and programmers. The data that has been obtained as a result of the interdisciplinary experiment has been summarised, analysed and applied once more in order to model the graphic and sculptural shapes presented in the exhibition, these being: the observation of an active biological system (ant colony) and an installation with data projection, a visualisation in two-dimensional drawings and three-dimensional sculptures of signals transmitted by various technical auxiliary devices, as well as the audification, using scientific tools, of sound signals imperceptible to human ear. The fact that from 2003 till 2007 Johansons studied at the Institute of Sonology of the Royal Conservatory of the Hague that he graduated with a bachelor’s paper titled ‘Information Structures for Organization of Sonic Events’, naturally explains the artist’s interest in sound structures, as well as his structural approach in turning abstract data into spatial entities. | |

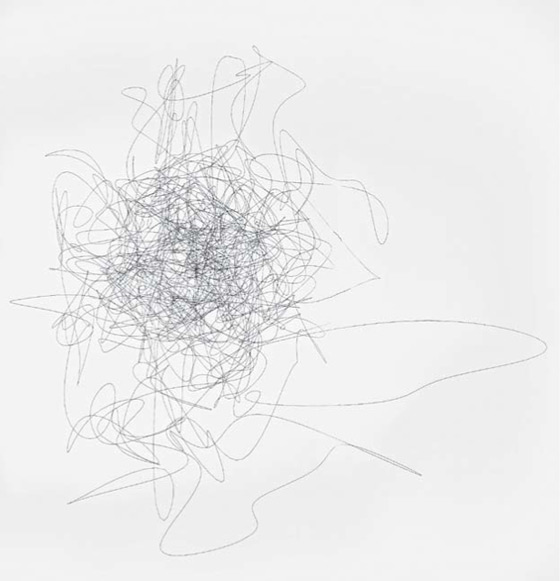

Voldemārs Johansons. Untitled. From the series Meanders. Ink on paper. 2011 Publicity photos Courtesy of the artist | |

| In the exhibition description it is pointed out that Attractors tells a story about chaos and its order. Also, in the only piece of detailed information regarding the works presented in the exhibition Johansons has noted that “shapes and volumes that may be observed in the physical environment (and have not been consciously made by human beings) are abundant with patterns and combinations of volumes that potentially have an aesthetic value”, and has re-ferred to James Gleick’s book Chaos: Making a New Science. Gleick’s book, first published in 1987, was the first popular scientific source where, without delving into higher mathematics, chaos theory and its elements have been described, for instance, the Mandelbrot set, the Julia set and the Lorenz attractor. No wonder that the exhibition in English is not Organic Patterns, which would be a literal translation of the Latvian, but rather Attractors, thus alluding to the peculiar forms of fractals, also called attractors, described in the framework of chaos theory. By definition, attractors are the depictions of all possible states of a system and demonstrate how narrow the border is between sometimes radically different development scenarios. For instance, one of the Lorenz attractors, when visualised in terms of plotted trajectories, resembles a butterfly with open wings. Similar data visualisation approaches have been used in art previously too, offering new aesthetic solutions. One of the most obvious examples that immediately comes to mind is the American digital media artist Aaron Koblin, who excited attention on a global scale with his technical solution for the creation of a video clip for the Radiohead song “House of Cards”. The innovative approach to data visualisation in this video was that the images of people, landscapes or objects as seen in the clip were not recorded with cameras or lights. Instead, 64 lasers and special data processing technologies were used to determine the relative distance between the objects and a sensor, and allowed to visualise it in 3D form. Thom York explained the group’s choice not to use any cameras, stating that “I liked the idea of making a video of human beings and real life and time without using any cameras, just lasers, so there are just mathematical points – and how strangely emotional it ended up being.”(1) A different perspective on an otherwise ordinary and familiar reality has also been constructed in Koblin’s series Flight Patterns (2009), where data from the USA Aviation Administration has been visualised similarly as in Lorenz attractors, namely, in the form of trajectory curves, revealing the density and intensity of flights in an extraordinary animation. Johansons, too, in an interview that can be viewed on YouTube, admits that as an artist he is interested how, in the visualisation of sound signals, by using mathematical methods it is possible to turn an abstract data curve into spatial structures. Moreover, the shapes resulting from this process are not of his design. Johansons is fascinated by the fact that the shapes vary and are different from each other, although the algorithm used for detecting the shapes was one and the same. This means that variation is inherent in the signals themselves. Hence the artist operates as a mediator between nature and the viewer, because he offers the data hidden in everyday reality in a form that the viewer can perceive. Nevertheless, the revealed shapes and patterns are not data that has been visualised with the aim of communicating information in a schematic, easy-to-understand and effective form – they do not have a functional purpose. What Johansons points to is the aesthetic quality of the graphic works and the fact that they already exist in nature, but in this case they have been depicted through the prism of his interpretation in two-dimensional drawings on a plane and three-dimensional sculptures. Furthermore, the observation of nature is not just a subjective point of view and its corresponding representation in art, but a much more accurate perspective that is possible to record only with a technical device, for instance, a seismograph and an accelerometer. As to the artist’s interpretation and aesthetic solution, Johansons has chosen to use a fine graphic line. This line has been obtained indirectly – from the interaction of fixed energy processes. According to the Russian Constructivists, who have always held theoretical contemplations on the line, point and plane in high regard, the line as a pictorial element is a solid, compressed channel of energy. What makes the line stretch in one direction or another, or to become curved instead of straight, is nothing else but energy. For instance, Wassily Kandinsky writes that in fact “the geometric line is an invisible thing. It is the track made by the moving point; that is, its product. It is created by movement.”(2) If a point as a pictorial proto-element is static, then the line is dynamic – it is a vector affected by force. | |

Voldemārs Johansons. View from the exhibition Attractors. 2012 Publicity photos Courtesy of the artist | |

| It is particularly interesting that Kandinsky, too, has conducted similar observations of nature, for instance, as regards the occurrence of line in countless phenomena in the mineral, plant and animal worlds. Kandinsky notes that “the schematic construction of the crystal is a purely linear formation (an example in plane form – the ice crystal).” A plant, too, in its entire development from seed to root passes from point to line and, as the line progresses, leads to more complicated complexes of lines, to independent linear structures, like the network of a leaf or the eccentric branch constructions of evergreen trees. “Some complexes are of a clear, exact, geometric nature and vividly recall geometric constructions made by animals, as, for example, the surprising formation of the spider’s web.”(3) Kandinsky does emphasize that one should not, however, draw false conclusions when comparing art and nature. The source material in each case is different and the basic characteristics of the material must not be left out of consideration: the proto-element of nature – the cell – is in constant movement, whereas the proto-element of painting – a point – knows no movement and is at rest.(4) By the way, Kandinsky has an opinion with regard to music as well, and the musical notation that consists of combinations of lines and points he defines as graphic musical representation which conveys the most complex sound phenomena in a language comprehensible to them experienced eye.(5) Johansons’ observations of nature are most tellingly characterised by the installation with the ant colony which is also the central object of the exhibition. Simulating the conditions of this ecosystem as closely as possible to nature, the artist has located the ant colony in a huge, transparent container, letting the viewer observe a biologically active system. Because ant movement trajectories in nature do not get documented in any form and thus under everyday conditions are not visible to the human eye, Johansons has visualised them and projected them onto the wall. Besides, the anthill with its huge and well-organised colony fits in well with the investigation of organic patterns and structures. The seemingly chaotic movement of the inhabitants of the colony is not so disorganised at all, as it may seem to a careless observer – each ant has its task which it dutifully carries out. The lines projected in this work have also been created by energy, only this time the authors of the lines are ants. You could even say that this installation is kinetic sculpture. In general, the exhibition delighted with its subtle mode of conceptual thinking and the merging of natural sciences and art in creative symbiosis. Voldemārs Johansons is an analytically and structurally thinking artist who offers viewers his own version on the analysis of fundamental elements of art. As a thorough and patient observer – such observations of nature require huge resources of time – Johansons demonstrates an artistic approach that is at the same time also imbued with the romantic and the mystical. We human beings are skilled enough to visualize and explain the data to be found in nature, however, this does not mean that the “musical notation” of nature is not an enigma and a miracle... Translation into English: Laine Kristberga (1) www.nme.com/news/radiohead/37990#DsF8J8p2P7qQ8Zww.99 (accessed on 10.02.2013.). (2) Kandinsky, Wassily. Point and Line to Plane. New York: Dover Publications, 1979, p. 57 (3) Ibid p. 104 –105 (4) Ibid p. 107 (5) Ibid p. 99 With thanks to Dr. phys. Linards Kalvāns for advice on Physics terminology. | |

| go back | |