|

|

| Bear of Happiness Elita Ansone, Art Historian Ilze Avotiņa. Bear of Happiness 07.05.–08.07.2010. Gallery Alma | |

| Ilze Avotiņa’s exhibition about happiness was introduced by an interpretation of Rogier van der Weyden’s (1399 or 1400–1464) altar painting Descent from the Cross. In a scene suffused with suffering, the pain of Mary and those who remain is infinite. The Apostle John and Mary’s stepsisters hold the collapsing Mother of Christ. In van der Weyden’s painting, Mary’s faint was an interpretation of events of the New Testament without precedent in the art of the Netherlands. The curve of Mary’s body in its rhythm imitates Christ’s pose, emphasizing their unity. The escalation of human grief screams out in gothic expression, but the figures have already gained a renaissance dimension and harmonious proportions. Apparently Ilze Avotiņa has admired this painting since her time at the art academy, especially the beauty of Christ, the peace and spirituality of the holy deceased. Her fascination with the composition didn’t fade through the years; quite the opposite – a time came in her life when there arose an inner need to create a copy of van der Weyden’s painting. In 2008, the artist’s father, painter Harijs Kārkliņš, passed away. He had introduced Ilze to painting and they were spiritually close. Ilze had already demonstrated her family’s creative legacy in the Krāsu attiecības (‘Relationships between colours’) exhibition in 2007, held at the LMS gallery, where in a joint exposition three generations: Harijs Kārkliņš, Ilze Avotiņa, Katrīna Avotiņa and Kristīne Luīze Avotiņa attested to their unity. With the passing away of her father, Ilze lived out the process of the descent from the cross in which, similarly to the painting, the family and companions participated. But the descent from the cross is also liberation and the attainment of peace. “At funerals there is something so beautiful and solemn, making one concentrate and prepare for the moment,” says Ilze. While living through mourning and reflection, painting and weeping, an interpretation of the altar painting Sāpju gaismā (‘In the Light of Suffering’, 2008) came into being. In Avotiņa’s version, although the figures, their placement and poses accurately duplicate van der Weyden’s altar painting, everything is different. There are changes, which the artist herself points out – the blood flowing from Christ’s wounds is blue, not red, and in this way it matches Mary’s blue dress, emphasizing the closeness between them. The opposing contrast of the colours and the highlighting creates a visionary scene, rather than the effect of an image of the here and now. At the centre of the yellow, divinely dazzling light, nine figures are active in the scene, participating in the shared event of lowering Christ’s body from the cross, but in essence each separately experiences the inescapability of death in life. The contrasts between individual fields of sheer colour – yellow, black, red, green, blue and purple – create a photo negative type of effect, a rather ghostly feeling, as if the activity was taking place in some strange environment, another dimension, perhaps in Paradise. | |

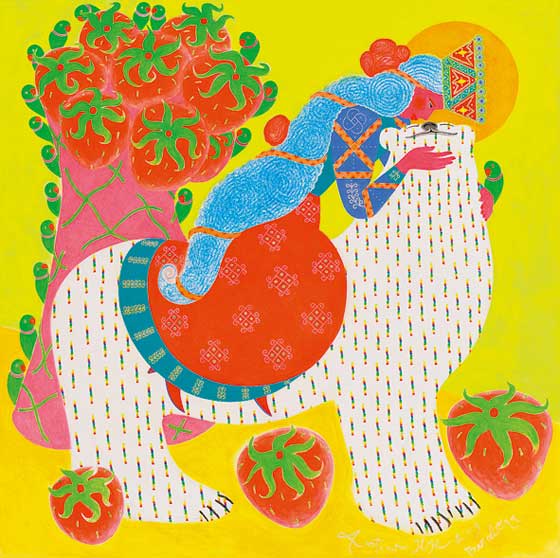

Ilze Avotiņa. Bear of Happiness. Acrylic on canvas. 180x150cm. 2009. Photo: Normunds Brasliņš | |

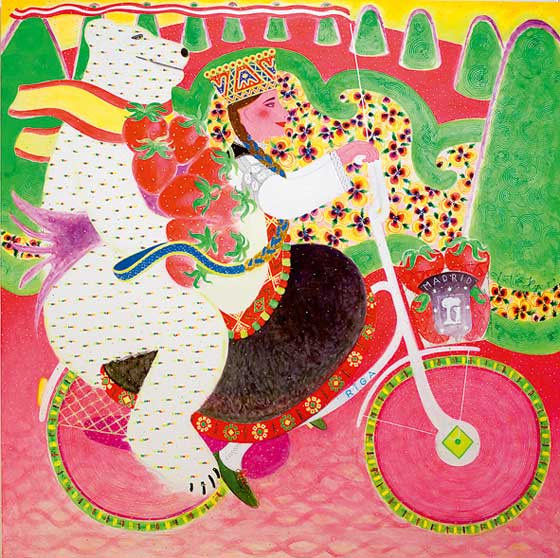

| Viewed in this way, it is possible to include Avotiņa’s painting among the phenomena of visionary art. In the Light of Suffering is the first work in which the artist has ever portrayed pain, in her creative life spanning more than thirty years. In the exhibition about happiness, pain was an inseparable component of the whole. To examine the original Descent from the Cross at the Prado, Ilze invited her family to go on a kind of pilgrimage. This was after In the Light of Suffering had already been created. If one allows and wishes for it to happen, the contrast with deep grief allows one to more powerfully experience the feeling of happiness which this journey duly provided. In Madrid, the Avotiņš family was greeted by a bear next to a strawberry tree – the symbol of Madrid, which somehow linked up with the Laimes lācis – the ‘Bear of Happiness’ of [writer] Andrejs Upīts. Ilze desided to take this Bear of Happiness back with her to Riga. Happiness, as we know, is a complex issue, which depends on our biological and psychological condition and is closely connected to our system of religious and philosophical views. The concept of happiness in recent history isn’t really that old. It is true, in the ancient world happiness was a subject of philosophical contemplation, and Buddha also sought happiness through peace of mind, but in mediaeval Christianity simple human happiness as such was repressed, and the idea of happiness began to be actively discussed again only in the Age of Enlightenment. Today, it is written in Wikipedia, among other things, that happiness is created by positive emotions and positive activities – a meaningful, joyful involvement in life – which to me seems quite a reasonable way of achieving happiness. Ilze states: “Happiness is to be aware that you are healthy, and to appreciate this as the greatest blessing. Each of us has to respond to the question “What is happiness?”. Happiness must be found within yourself. You have to find your mission, your challenge. In all of my paintings I have thought about the issue of education: how to create a spiritually healthy person?” In four of the eight paintings of the exhibition a large, white, smiling adorable thing in the shape of a bear serves as a metaphor for happiness. The bear is a large, white, glittering embodiment of joy, and that is literally how it has been painted: with a white fur coat strewn with fluttering rainbow flecks. It is a surprising, unusual image, which by alluding to Upīts’ Bear of Happiness, reminds one of the story Sūnu ciema zēni (‘The Lads of Moss Village’) and the slipshod life in that village. The story was written in 1940 and based on a play called ‘Bear of Happiness’. “Moss village is to be found so deep in the Great Forest and so far from other human places of settlement, that only on the quietest nights of the month could one hear the nearest neighbours’ cockerel crowing”. It is almost unbelievable that, in the reality of globalization, the genesis of Moss village thinking still remains. For me, a comparison with Dogville (from Lars von Trier) seems apt, corresponding to Latvia and similar to our present day, where people’s apparently ‘innocent’ selfishness, step by step, transforms into frightening cruelty. However, Avotiņa’s way is not to criticize – there is not a word about the bad. She has a specific objective, task, goal – to lead us out of suicidal self-destruction. Not to denigrate and to criticize, but to inspire and to elevate. In essence it is neo-shamanism. Like a kind of sorcery – the thing that you wish must be attracted, imagined, visualized and called by name. It is of significance that ancient and esoteric techniques are also in a way close to currently popular psychotherapy methods and concepts of personality self-development. For example, the Human Potential Movement / HPM, which first appeared in the 1960s in the West and attempts to develop quality of life, happiness, creativity and ful-filment. The idea that people’s mutual social networks can bring about positive change and develop the creative potential which exists in each of us is attractive. The interaction of transpersonal psychology also emphasizes esoteric, physical, mystical and spiritual aspects, which tie in with New Age views. The human potential movement also has therapeutic goals, which aspire to humanize social network cooperation, and try to reduce the social isolation of individuals. For the past two years the artist has been painting Latvian symbols into her works, delving into their meanings and trying to activate the energy of the signs. In the painting Tuvošanās (‘The Approach’), a girl in an ornate Bārta national costume has set off on a joyful journey by bicycle with the Madrid symbol – a bear with a strawberry tree under its arm – on the baggage carrier. Dizzying ornamentation, bands and groups of symbols and patterns, rhythm and movement, the flags of Latvia and Spain, luminescent opposing colour arrangements create an optically shimmering, sparkling carousel effect. More fantastically evocative is the title painting Bear of Happiness, in which the mythology of the abduction of Europe can be recognized. | |

Ilze Avotiņa. The Approach. Acrylic on canvas. 180x180cm. 2009. Photo: Normunds Brasliņš | |

| Folk symbols are incorporated in both works, with the sign of the sun dominating – the giver of life, light and heat, the symbol of eternal movement; because the sun always returns, it is also the harbinger of a new beginning. The sun, by providing light, makes things visible; it is the source of cosmic intelligence. In many places the wavy line of the sign of Māra also weaves through – the ruler of fertility, earth and water, as well as ‘the little brushes’ of Laima – protector of the soul and spirit. Ilze creates her symbols and moves them forward with a deeper rationale: to give us more strength and success. Valdis Celms has conducted the most comprehensive research about Latvian signs yet, published in his book Latvju raksts un zīmes (‘Latvian ornaments and symbols’), and this book is also used by Ilze. Can we know what effect a sign, its colour, form, its placement in relation to another, has on a person? Experts maintain that signs do work. It is true that in chaos theory the huge volume of unpredictable interacting forces do not offer an opportunity to predict the result of the activity of these forces very far into the future. However, for those who believe in some kind of cosmic intellect, all of this natural force mystery is a logical order, and the matrices of Latvian signs and symbols are the visual structures of order. Theoretically reasoning, if we think about the meaning and the significance of each sign, we bring into our consciousness the respective code, which, although it also interacts with all of the other codes that are around it, still influences our thoughts and spoken words; in turn, if these words also reach other ears and minds, the thoughts are spread further. Belief in an interactive link between a person’s psyche and matter, and the world of living creatures, makes one look at Avotiņa’s art in the context of animism as well. The view that everything has a spirit and soul was important in the ancient world. Meanwhile, the view of Lucretius of Ancient Rome, that all things radiate small particles which affect the sensory organs, is, in a surprisingly similar way, reflected in the vibration of Avotiņa’s paintings created by tiny dots, as well as the optical effect of luminescent colour, which, going further and consistent with 20th century research in theoretical physics, can be contemplated in relation to quantum’s miraculous nature as the art of quantum mysticism. I am very interested in this integral thinking of contemporary artists, when even primitive religious concepts are being brought into the various mechanisms of psychological and sociological, as well as physics theory, and experiments with neo-shamanism or elements of neo-paganism take place. This leads us to remember the original function of works of art as ritual and cult items. I’d like to place Ilze Avotiņa’s paintings with Latvian signs and symbols into this niche, as all of the signs have been painted with a shamanistic goal. Turning to the other works in the exhibition, it shouldn’t be forgotten that they are dedicated to the six months spent living in Barcelona, and came into existence when the family joined Kristīne Luīze Avotiņa’s studies at the Escola Massana Art School in 2009–2010. “We, my family, we were all together, away from our social circle for half a year! I could devote myself entirely to my thoughts. And I understood that I need to love, work and do everything more simply,” relates Ilze. In the Bear of Happiness exhibition there were many specific references to Barcelona and Madrid, the famous Gaudi Parc Guell sculpture and ornamentation, a colourful parrot in place of a Latvian sparrow, the unusual Madrid strawberry tree and archetypal Spanish women. Ilze had also hoped to paint a famous Spanish woman, and Barselonas apskāviens (‘Barcelona’s embrace’) is a portrait of Penelope Cruz, taken from some magazine, with the actress lying in a fond embrace against the bear, literally blending into its sunny, yellow bulk. In Barcelona an experiment was carried out, too. In 1992, there was an experiment with luminescent colours, becoming Avotiņa’s unique choice for all of her creative work, whereas in 2010, the artist purchased phosphorous colour which can only be seen in the dark. This is used in the painting Paloma, after a reproduction of the drawing Woman with a Bird Mask which was purchased at the Picasso Museum. It may seem surprising that in an exhibition where feminine creatures dance, embrace, love, and play with a large white bear, there is also an image of a fighter: the Archangel Michael (Sargeņģelis – ‘Guardian Angel’). Its prototype is from Piero della Francesca’s (1420?–1492) polyptych Saint Augustine (1460–1470). But this indicates that every choice in our lives requires a fighter’s bearing, and the author, just like an archangel, is carrying out a mission: to bring happiness, to create happiness, to paint happiness. Her choice is an unbending consistency and a clear goal, similar to that bringer of light, the Archangel Michael – the fight of good against evil. The Bear of Happiness exhibition was an invitation to a process of individual transformation and an initiation into spiritual self-awareness, in the name of love and happiness. /Translator into English: Uldis Brūns/ | |

| go back | |