|

|

| ‘The train hasn’t left yet’ Iliana Veinberga, Art Historian A socially-oriented art and literature project | |

| From 14 August to 1 November viewers will be able to attend the exhibition Vilciens vēl nav aizgājis displayed in eight railway stations on the route Riga–Dubulti(¹). The exhibition is being organized by the Art Management and Information Centre and curated by artists Aigars Bikše and Kristaps Gulbis. The ambitious concept of this project results in an adventure, where tragicomic real objects alternate with fundamental issues about art and works of art, in total creating a confusing experience which one might dearly wish to unravel together with the Minister of Culture and a psychoanalyst. Focus on the suburban railway line Riga–Dubulti Artists Aigars Bikše and Kristaps Gulbis are known as conceptually oriented authors, both on their own and, more often, working as a team. The charm of their work is that the content, which might be topical, social or anthropological, at times presented in an ironical, perhaps even critical way, is closely connected with the form, whereby the artists play with the ‘classical values’ of art, for example, exercises with form, conditions of representation, allusions to authority or the canon of art. Such a union of contrasts creates a semantic tangle which is rather interesting to untwist. This principle is also followed in their work as curators, and the exhibition Vilciens vēl nav aizgājis conceptually continues this tradition. The choice to use the railway as the key theme is very appropriate. Firstly, the railway industry in Latvia has very old antecedents and a colourful history. Secondly, semantically the railway is a very capacious concept, amenable to the use of various metaphors, from politically ideological to emotionally private and even sentimental ones. Lastly, the railway offers a multi-faceted and well-attended space for exhibiting art. It’s an excellent start-up capital to work with. The main focus of the exhibition is to reduce the gap between the ‘cultural elite’ and ‘the rest of society’, using the most affordable means of transportation – the train as a physical platform where an individual, daily life and art meet and become a theme for works of art. | |

Izolde Cēsniece in cooperation with Uldis Bērziņš. To Take a Glance. Installation at Majori train station. 2010 | |

| Daily prose and the snow-capped peaks of art Do I belong to the cultural elite, or am I a mere mortal? The question constantly nagged me. On the one hand, I don’t usually take the train, so in this case my only aim in taking the train was to see the exhibition and the concrete authors. The conclusion might be that I am not in the category of those ‘consumers of art’ who will be encountering these artworks suddenly and repeatedly, for example, while waiting for their daily train-ride to work in Torņakalns. Another difference might be that regular travellers will see the exposition at their train station only, but I will have seen all of them. From this point of view, I am an outsider who has wandered into the territory of the railway without making its prosaic routine my own. I must warn the reader in advance that the one-way cost of taking the train and getting off at every stop will be at least twice as expensive as buying a return ticket Riga–Dubulti (unfortunately, there is no other way). A company of several people may find it more economical to go by car; however, by using this approach, the basic concept of the exhibition is lost. On the other hand, visiting these expositions, or, in some cases, seeking them out, and the difficulties experienced during this crusade, made me feel like a person who comes into contact with art for the first time, and during these irregular and almost primordial moments of acquaintance, I had no choice but to try to set the boundaries myself. The joy of first discovery. For example, the exhibition was hiding from me at Riga railway station, and even the employees of the information centre could not tell me where it could be found, or that there would be any exposition in the station at all. Books attached to the wall of the waiting room, with an invitation to take and read them, looked like a rather stimulating ‘installation’, but I thought – that couldn’t be it. And it wasn’t. The next train station – Torņakalns – came with a similar surprise. Where is that work of art? Ah, a printout of a literary text, that’s by Eduards Aivars, OK, but the other one? Voldemārs Johansons. My travel companion and I half-jokingly decided that the humming shack for electric switchgear or tool storage must be the ‘installation’. Surprisingly and confusingly, we were almost right. The installation was not the hut itself, but a humming and vibrating log placed in front of it – we had walked past it several times. The work of Aigars Bikše was hiding in Imanta train station so discreetly that, having walked into the small ticket office several times, we started wondering (knowing the artist’s slightly anarchistic attitude towards art) if the torn pop-music posters with obscenities written on them would be his contribution to the project. But by this time we already had a search strategy in place, based on the experience in Riga and Torņakalns, knowing that we had to look for a non-functional object which does not fit into the given environment due to its lack of function. That’s why a ‘creative’ advertisement for a bookstore, a locked hut or previously unseen posters at the train stops would be good candidates for artworks. Indeed, the democratization of art, and overcoming the divide! | |

Voldemārs Johansons. Opus 22. Installation at Torņakalns train station. 2010 | |

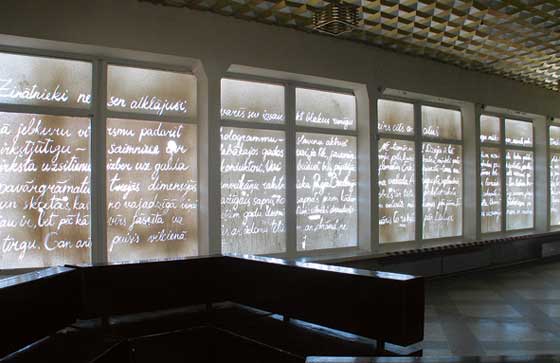

| Works, artists and management Of course, the approach I describe is more for amusement, because the majority of the works were fairly easy to notice and they embodied the given theme of the railway in diverse ways creating tension with the environment and the other works. The exposition at each train station consists of a work of a writer or poet and a visual artist. It is a sweet idea to bring together the masters of the word and visuality because, although in daily life people are surrounded by various media which often interact and enhance each other, in Latvia there is a tendency in art to place everything on its own shelf and even attach a user’s manual to instruct what is meant for what use. That’s why the works which look like collaboration between the two media are immediately powerful (especially the works of Uldis Bērziņš and Izolde Cēsniece at Majori station). In some works this collaboration is not so evident, but still a viewer with some imagination will easily find a poetic connection. In very rare cases there is no connection at all, making one wonder whether the text was meant for a completely different train station or the pieces have been brought together by chance, etc. I am not going to draw conclusions about writers based on a fragment of a poem or a literary text, but as regards visual art I must admit that the sculptural works displayed in the stations were really impressive (for example, the objects of Ginters Krumholcs or Edgars Osis). Installations, especially sound installations, require a more attentive viewer (or user), therefore the artists must be very careful about their choice of environment and the placement of the work. From this point of view, it seems that there could have been more understanding and support for the artists’ creations, for example, at Dubulti train station, where the Soviet style interior with its distinctive decorations was very inspiring, but also very limiting as to what can be installed there. The eye-catching object by Asnāte Bočkis had simply become unnoticeable, and even when found wouldn’t attract the attention this ingenious and playful object ‘railway’ style deserved. By the way, the new names alongside experienced artists was the second pleasant surprise, next to the mixing of media. The contribution of each author, their mutual interplay and the ability to blend into the surrounding environment would be worthy of a more extensive discussion, as each of them inspired diverse and ephemeral thoughts. But this is hindered by limiting factors, which do not allow a fussy viewer to pay undivided attention to the enjoyment of the art – there are some half-finished or unfinalized details, technical problems or adjustments introduced by railway employees to suit their own needs. For example, it seems that it is not enough to attach a few stanzas to the walls of the station, so as to motivate the train passengers to read poetry instead of the popular press and to return a ‘cultural aura’ to the railway. Yes, the travellers will read these poems, but will that motivate them enough to search for more, and to read more poetry? I seriously doubt it. Taking into account that each of the authors has already published books, it would have been more productive to install vending machines which, for a bit of money, would dispense books of poems instead of a newspaper. Of course, this would require larger expenditure and there would be a number of additional complicated requirements to actually install such vending machines, but the result would definitely be much more impressive. Certainly, before any reproaches are addressed to the organizers of the exhibition, one must stop and admit that, given the limited resources in Latvia, exhibitions of contemporary art are often not the result of a perfectly implemented original idea, but the best possible under the circumstances, bordering on charity work and DIY culture. To be honest, the attitude and the set of artists chosen for the exhibition Vilciens vēl nav aizgājis is splendid, just that there is the constant feeling that, under more favourable conditions, the result could have been considerably more explosive. (¹) Riga (Kirils Panteļejevs, Laima Muktupāvela), Torņakalns (Voldemārs Johansons, Eduards Aivars), Zasulauks (Edgars Ošs, Jānis Rokpelnis), Imanta (Aigars Bikše, Inga Ābele), Lielupe (Kristaps Gulbis, Gundars Ignats), Bulduri (Ginters Krumholcs, Arvis Viguls), Majori (Izolde Cēsniece, Uldis Bērziņš), Dubulti (Asnāte Bočkis, Inga Žolude). /Translator into English: Vita Limanoviča/ | |

| go back | |