|

|

| Bauš’s avant-garde Jānis Borgs, Art Critic A few impressions, looking at the life and work of Auseklis Baušķenieks | |

| Now we can say – he has been studied, researched, counted, measured, partially evaluated… The painter Auseklis Baušķenieks. A constant in our art, and fittingly he has been placed with respect and honour among the classics. But the path to get there has not been straight-forward and lighted up by the sun of triumph. And for this reason we might look at the life of the artist as an unusual adventure, where the lofty course of art is woven into the spirals of a master’s destiny. The quick flow at times was broken up into sharp facets by harsh changes. So examining the personality of Baušķenieks is like turning a diamond during valuation – some facets sparkle unexpectedly brightly, others vanish into shadow, and there is ever a mystery to be discerned… People of my generation noticed Auseklis Baušķenieks as a vivid accent and an individual unlike anybody else in Soviet era art exhibitions of the 1960s–80s. Of course, the ruling power tried to artificially cultivate rather conservative and ideological approaches to art. And quite many artists in one way or another paid their dues to the demands of the authorities. Now some of them describe it, with a rather hypocritical bravado, as the “collaborationism of the Latvian intelligentsia”. This, however, could be a substantial subject for a separate study. But the thought behind it all was fairly simple and mercenary – to get on with the aliens peacefully and without going overboard, to secure a better livelihood, sometimes a smoother glide up the career ladder, a few laurels… Or even through ‘the approval of the emperor’ to improve the lot of our own society… The long list of artists will contain very few of whom one could say with 100% certainty: here is a true ‘orthodox’ believer, in the communist sense of the word, whose thoughts and works are in complete harmony with the ideals of the ruling power. On the other hand, not so many artists retained sterile uncompromised purity in their art. Thus each new ‘maverick’ was greedily noted, attracting public support. It seems that Auseklis Baušķenieks can be counted as one of these. The Neputns publishing house has just published a superb and comprehensive book about Auseklis Baušķenieks, where, besides the already known facts, we discover a number of revelations and surprises which were not known to the public at large. For this we extend our gratitude to the team of authors behind the book. In the context of the previous, we can find in the book a few testimonies that Baušķenieks also had occasionally paid his dues to the ruling authorities. Somewhat formally, though, like a house pet who marks its space and reminds us of its existence. Nevertheless, nearly all the body of his art as a whole has remained autonomous in this respect, in line with his own ideology and life philosophy. That in itself was a sign of strength of character, and even heroism – to retain independence within his own artistic territory. | |

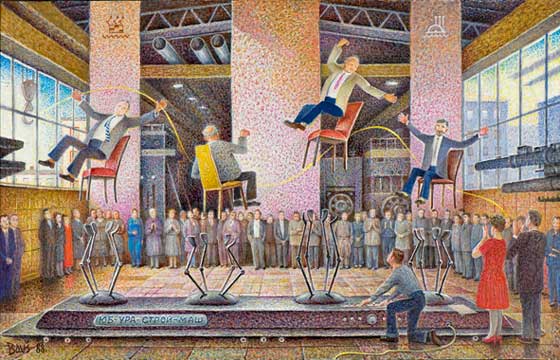

Auseklis Baušķenieks. Party in the Robot Factory. Oil on canvas. 63x99cm. 1988. Photo: Normunds Brasliņš | |

| At Riga Art Space, curator Inga Šteimane recently put together a fundamental exhibition of Latvian art of the Soviet period. As we could see in the artworks, neither the presence of the authorities nor gravitation could stifle the propensity of artists to reach towards a freer language of form, to work with the expressiveness of art. In the overall landscape these tendencies made it quite problematic to conform to the officially declared orthodox social realism. The ideologues of the Communist Party had a lot to do, so that the desired result could be presented as real – creating something similar to the so-called Potemkin villages. And in the view of some ‘reviewers’ the art of Auseklis Baušķenieks could be interpreted as a new form of social realism, so to speak – ‘work in progress’. The master himself consistently stood apart from all this mess, and tilled his own uniquely detached and original furrow in the field of Latvian art, moving in a direction well apart from any common movements. What initially attracted the attention of the public? Because, as already mentioned, he was immediately noticed for his originality. We could emphasize several factors here. First of all, we must remember that Auseklis Baušķenieks as an artist was reborn with a new form of expression after a very long, almost ten-year long break, and this coincided with Khrushchev’s thaw – just after the 1956 policies of de-Stalinization. The new and more favourable climate of the era inspired hope in many, and Baušķenieks, too, came up to the surface, quite like a mushroom in the ‘moss-covered marshland’ of Latvian art. At that time he was 46 years old – an age when not many can start a new life. He was able to, and did so with extraordinary energy. In Soviet cultural life there was a moderate turn towards the West. This direction until recently was very much taboo. One of the manifestations of these new tendencies was a rediscovery of various values of Western culture. For instance, Soviet people were greedily enthusiastic about French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Today we can only wonder how one could go into raptures about a hundred year old classic as if it were the latest innovation. Every self-respecting cultured person admired Van Gogh and Gauguin, and had on their wall the amous portrait of Hemingway where the bearded face of the American writer sinks into the coarse knitwork of his sweater. These were the new icons of the Soviet society. It is hard to say how ‘calculated’ or organic the artistic form of Auseklis Baušķenieks’ personal renaissance was, expressing itself as it did in a manner akin to Georges Seurat’s pointillism. Baušķenieks himself tried to ward off any such comparisons. Without any belittling of the master’s individuality, it could be remarked that the whole history of art is like one single bundle of mutual reflections. So there is nothing to disapprove of in such comparisons. In this respect he was not alone. Similar ‘parallelisms’ could be observed in the works of other masters of that time, for example, Boriss Bērziņš and French cubism. Or Jānis Pauļuks and the tachist techniques of the expressive colour spatterer Jackson Pollock. Certainly, the wider audience of that time knew little of Seurat, Braque or Pollock. Such delicacies were available mostly to specialists tolko dlja sluzhebnogo polzovanija(1) – for official use, so to speak. And not infrequently these reflections or interpretations of foreign classic artists in the paintings of our masters were perceived by the public as particularly courageous, daring and original. They were considered to be almost a manifestation of opposition to the dogmas of social realism. All these elements must have been present in one way or another. Let’s not slip into purist snobbism, let’s remember here only the complicated essence, psychological vibrations and motivations of the development process of artistic expression. And to have petty discussions about whether or not Auseklis Baušķenieks is a ‘student’ of Seurat today would be rather naïve. He is and remains a phenomenon in our art. Much more surprising than anything else is the drastic change in the personality of Auseklis Baušķenieks which took place in the 1940s–50s. We are talking about two almost completely different individuals. The first one is the youth who was educated in pre-war Latvia (he studied architecture at the University of Latvia and graduated from Ģederts Eliass’ figural painting workshop of the Art Academy of Latvia during the years of the World War II). He revealed outstanding academic drawing skills, altogether breaking out of the framework of traditionalism. In almost all of the examples of his artworks from that time (and they are very scarce) we can observe a ‘taste for form’ or the enjoyment of artistic expression, which later, in the Soviet years, was to be damned as evil formalism. One could surmise whether, if there hadn’t been those years of major upheaval, Baušķenieks might not have become a brilliant Latvian surrealist. That predisposition is continually present in his creative oeuvre. Similar tendencies can be detected in his early period, and they become more obvious in his art of the Soviet period. It must be added here that even during the upsurges of Soviet liberalism, surrealism was considered to be the worst and ideologically the most detrimental movement in art. The reason for this was that it was not just a pure game with form, but it conveyed uncontrollable and veiled messages of the subconscious. Surrealism in the visual arts could be likened to literature which always made the censors extremely jumpy and full of suspicion. But fate had ruled differently, and this line of development was not to be. The Baušķenieks we all know is so completely different from the artist he was in the beginning that he seems like another person. Baušķenieks’ later move towards pointillism, with tentative elements of surrealism and symbolism, seems to make much more sense. This is logical, because ‘academic’ surrealism during Soviet times would have elicited fierce counter-measures from the censors. But here everything seemed like the playing of an artist who is a bit naïve, and nobody sought to point out any controversial tendencies in the forms of Baušķenieks’ ironically good-natured pictures. The censorship did at times search for controversy in the labyrinths and rebuses of the literal message itself, occasionally perceiving with fright “the defamation of Soviet reality”. With regard to [the creative work of] Auseklis Baušķenieks we can speak about a rather finely balanced set of attractive elements, which were quite acceptable to the ‘average viewer’: modern form, acutely topical themes, the ‘comprehensibility’ of the message and the always coveted and sought-after hidden messages. During the Brezhnev era especially, people were keen on looking for the hidden meaning of works of art, to ‘read between the lines’. And the artists often used this opportunity – for example, conveying some finely modulated ambiguity, where everything seemed as if correct and no rules were broken, but the viewers could see there something else that was not directly expressed. This brings to mind an example from more recent times, the ingenious joke played by Stendzenieks’ advertising agency in connection with the visit of the President of the United States, George W. Bush. Apparently flattering welcome posters were placed along the route of the President. The posters featured a portrait of the President with a caption in English – Peace Duke. Everything was fine, and everyone was happy, unless someone read this caption from the point of view of the Russian language (‘Peace Duke’ is a four-letter-word when transliterated into Russian – Ed. note). But who could object? And here it had happened quite in the spirit of Bauš. Hidden meanings were actually a stick with two ends, because the censors anticipated these underlying meanings and maniacally searched for forbidden subtexts in all works of art. Time and time again this led to a serious paranoia of suspicion, and various as if subversive double meanings were found in many works where even the poor old authors themselves had not meant anything other than what was directly expressed. In this Soviet tragicomic farce Auseklis Baušķenieks also ‘copped it in the neck’ a few times with the said ‘other end of the stick’, earning a ban on publicity lasting several years. Today there is an evident tendency to heroize such cases of ‘suffering’ and to label one or another of these ‘repressed’ artists almost as ‘heroes of the opposition movement’. That, however, would seem a propagandistic exaggeration. Any artist, for one reason or another, could end up in the role of ‘sufferer’ (because Big Brother was always vigilant), and emotions and feelings ran high. But now, looking at it from a distance, those late-period Soviet ‘repressions’ are more like Lemonade Joe, the 1960s Czech parody of a western, where the evil-doer Hogo Fogo performs the ‘gruesome torture’ of the main hero by burning out a hole in his blue scarf with a cigar and adding maliciously that “a little torture is a little fun for us”. | |

Auseklis Baušķenieks. Kinetic objects. Photo: Normunds Brasliņš | |

| The ‘resistance’ of Auseklis Baušķenieks nevertheless did not go beyond the tolerance levels of the Soviet authorities. The kitchen and work vecherinkas [parties] were popular venues for telling anti-Soviet jokes. If there were unknown people present, in order to neutralize a potential stukach [informer] people would start with a cautionary phrase: “Did you hear what a scoundrel told me yesterday…?” Meaning, I don’t agree with this, but listen to what slanderers are saying. Usually, there were no repercussions for such jokes, if they were not told in a public place. Looking at many of Baušķenieks’ works one was always left wondering whether this ‘bloke’ is joking or he is deadly serious. He definitely possessed a rather nuanced ‘English humour’ and a large dose of irony and self-deprecation, which wasn’t just a principle of artistic expression, but also a deeply ingrained trait of character. This is remembered by everyone who had the honour of being on friendly and private terms with him. But Baušķenieks’ art was not always evaluated favourably by colleagues, his contemporaries. He was at times labelled as a ‘naïvist’ or simply an infantile ‘illustrator of narratives’. The ruling assumption in the evaluation of art was the priority of form and aesthetics of the artwork, the ‘tradition of Latvian painting’, etc. At that time there was a tendency of progressive allergy to content, narrative and ‘socially relevant themes’ in Latvian art. But Baušķenieks remained immune to snobbish mockery and consistently held his position. He chose to remain an original loner. But if we probe deeper, the occasional naivety of artistic forms or anatomy of images, which could easily be misunderstood as being a kind of crumminess, was rather carefully programmed, stemming from the skills cultivated and artistic perceptions that had emerged at the time of his first alter ego – in the 1940s. Very few people recognized this, and so the majority of the viewers were not aware of the academic culture that gave roots to Auseklis Baušķenieks’ art. Only by a more detailed analysis of the artistic forms in Baušķenieks’ painting and examining various refined treatments one can feel – there is something hidden behind this, trying to come out. This as if naïve comedian owns a suitcase of ‘secret’ knowledge and only the gullible will fall into his trap of clownishness. Yet the surprise remains – how can one person unite two seemingly unconnected artistic souls, which manifest themselves at different times? Here we must remember that Auseklis Baušķenieks in the blossoming of youth experienced heavy social conflict and the turmoil of World War II. The familiar, optimistic way of life was torn to shreds, relatives were scattered all over the world without trace, and his own existence was under threat with death constantly breathing down his neck. Mobilization into the German army turned Auseklis Baušķenieks into a European war tourist in Germany, the Netherlands, France… He was lucky enough to be stationed outside the active war zone, in the ancillary service. But the fate of being a prisoner in the West and the pressure of filtration camps could make even the toughest ‘Rambo’ nervous. Auseklis, being a person of sensitive nature, was definitely not one of these. He could have easily ended up in Siberia. Not in vain a Russian officer – a Smersh filtrator – classified the young artist as a portraitist of fascists and hitlerists. The uncertainty and insecurity about his future evidently motivated Auseklis, on his return to Stalinist Latvia, to abandon the ideologically slippery activities with art and turn to a more discreet way of making a living in the field of ‘artistic decoration and graphic propaganda’, as well as working as a teacher of children in the drawing club at the Riga Pioneer Palace. The master emerged from these ‘underground activities’ only in 1957, when he regained hope for a better life. That year, for the first time after the war, Auseklis Baušķenieks participated in the Latvian fine arts exhibition in honour of the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution, which was held at the State Museum of Latvian and Russian Art. This development brought its rewards, because in 1961 he was admitted to the Artists Union of the Latvian SSR. Thus the former ‘German soldier’ hounded by fate became a fully-fledged Soviet artist. But heightened caution and mistrust of the ruling authorities, based on bitter experience, it seems, remained with him all his life, perhaps engraved in his bones. In any case, Baušķenieks avoided speaking about these dramatic years of his biography. His frame of mind can be also illustrated by a minor but curious episode of the late 1990s, that is when Latvia was free again, when any kind of repressions by the Soviets against our citizens were unimaginable. At the time, after attending a few exhibitions, the British Ambassador Stephen Nash had become interested in the art of Auseklis Baušķenieks. He decided that he would like to purchase some works for his collection. The diplomat requested that I be the mediator and introduce him to Baušķenieks. In the beginning everything went well, and the artist was most forthcoming. But an hour before the appointment, I received a phone call and heard a rather frightened male voice: “What does he (the Ambassador – J.B.) actually want from me? What’s he got in mind?” It sounded like the scenario of an old spy movie, where a base provocateur tries to lure an honest Soviet person into the net of Western agents and make him ‘sell out his Fatherland’, but the person is resisting with all his might… Needless to say, the anticipated meeting (and the deal also) did not take place. Because Stephen Nash had thought that he’d clearly defined his straightforward wish. It became clear – it would not do to trouble the elderly man with his attentions. If we look at Auseklis Baušķenieks’ life in terms of the dimension of time, we can establish the development of two different personalities in the one person. But Baušķenieks was even more complicated than that. He had another deep passion besides his artistic interests – radio technology. In Soviet times this was a very ‘fashionable’ hobby. But even this Baušķenieks carried over to his art. Fooling around with technical equipment led to the creation of various kinetic objects and installations. This fact is completely unknown to the wider public, because the objects were created for ‘private use’. In the 1970s in Riga and elsewhere in the larger cities of the USSR, there was a limited growth of kinetic art. At that time, due to ideological considerations (after all, here one could not apply the formula of ‘enhanced social realism’), it was linked to design. Kinetic art was only one of the forms of modernism which continued to break through the asphalt of Soviet ideology. The 1960s–80s saw the birth of what today we could call avant-garde or non-conformist art. Unfortunately, Baušķenieks did not take an active part in these processes, mostly presenting himself as an original painter. But now, after the various revelations in the master’s inventory, he should, with the greatest respect, be rightfully viewed as one of the pioneers of the Latvian avant-garde. It was this aspect of Auseklis Baušķenieks’ work, one would think, that was first noticed by the German curators who were creating an exhibition of Latvian avant-garde art in West Berlin, in the late 1980s. Before that, no one had regarded him as an avant-garde artist. It is true, his ‘intimate’ kinetic objects were not on display at the exhibition in Berlin, only his paintings already so familiar to us. With years of experience behind him, the rather quiet artist was unexpectedly included in the vivacious company of ‘the young and angry’. The uniqueness and absolute originality of his art took the Western art viewers by surprise, no less so than the ‘outbursts’ of the new radicals. This was completely unexpected, because Soviet art was generally associated only with the stereotypes of social realism (the Berlin Wall had not been destroyed yet, and all these artists were still members of Soviet organizations). This was like an almost scandalous dessert served to the Western public – look at what has been thriving in the greenhouse of Soviet culture! The phenomenon of Baušķenieks’ art should also be viewed in the context of the Soviet atmosphere. Had there not been the unpleasant ‘pressure’ and the ‘carbon monoxide fumes’, the ‘permafrost’ and the ‘draughts’, it is doubtful that today we would have this kind of Auseklis Baušķenieks. And the rest of them, also. Would it be appropriate here to recall the factor of mycelium? Does Auseklis Baušķenieks belong to the avant-garde? Or does he belong only to himself? This will have to be assessed with the distance of time. One way or another – Bauš is Bauš. An exhibition in the White Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art Blēņu stāsti. Auseklim Baušķeniekam – 100 can be seen until 24 October. – Ed. note (1) “For official use only” (from Russian) – Ed. note /Translator into English: Vita Limanoviča/ | |

| go back | |