|

|

A ‘Patchwork Fantasy’ in crisis conditions A ‘Patchwork Fantasy’ in crisis conditions Margarita Zieda, Theatre Critic | |

| ‘Patchwork Fantasy’ is the Swiss director Christoph Marthaler’s challenge to crisis time thinking. In conditions of material breakdown, he encourages us to take a look at the previous spring collections hanging in the wardrobe and to allow our fantasies to run wild, by organizing a magnificent ordinary person’s fashion parade on a strip of striped brown, white and green tattered carpet. Our sensation of life begins with clothing. Not always the best. ‘Riesenbutzbach’ is the name of the theatre project by Marthaler and stage designer Anna Viebrock, which this year was included among the ten most notable performances from Austria, Germany and Switzerland in Berlin’s ‘Theatertreffen’. This where each year, for three weeks in May, all that has been the most significant in German language theatre during the past season is shown. Theatertreffen does not see as its role to reflect the latest trends: the review includes the most diverse aesthetic and artistic ways of thinking, which a small jury of professional critics has selected as the most important from the huge repertoire of German language theatre. Whatever is worthy of the most attention. Usually it is difficult to find a common denominator for the works, but this year was the absolute exception, as nearly everything worthy of attention in the theatre was related to the study of people in circumstances of economic crisis. | |

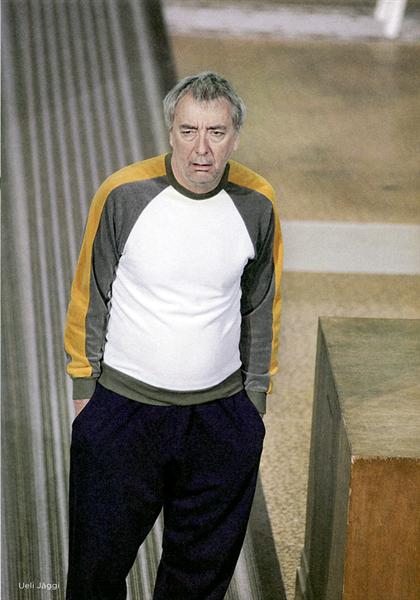

The theatre project 'Riesenbutzbach' by Christoph Marthaler and Anna Viebrock. Ueli Jaggi. Publicity photo | |

| The latest dramatic work by Nobel Prize laureate, Austrian writer and playwright Elfriede Jelinek, ‘The Merchant’s Contracts’, subtitled ‘An Economic Comedy’, which the Theatertreffen presented at Hamburg’s Thalia Theatre, was written shortly before the situation became global, even before the banks of the world started to collapse and investors lost everything that they owned, including themselves. The concrete reason for the genesis of ‘The Merchant’s Contracts’ was two bank scandals in Austria (where client pensions were lost due to speculation), as well as reflection about the virtual money system as such, which promises a rise in living standards, but is also able to ruin a person completely – even though it is in itself a total fiction, a real non-being, a zero, a void, nothing. Jelinek has set out her poetic reflections in a 99 page text without, as Germans tend to say, “full stops and commas”, without even separation of the text into persons and dialogues. The first 20 pages of the gigantic torrents of text take place in a small investor’s head, the bank employees’ response runs over the next 40 pages, creating a “chorus of the aged”, and the last 40 page text of the conclusion is left to “the Angel of Truth” Heracles, who lost money through speculation and subsequently axed his family to death. In her dramatic work Jelinek does not get involved with a search for the causes and reasons for the global economic collapse, she works with the language which can be heard in banks, with the rhetoric of recession, transforming language into a monster. German director Nicolas Stemann, who is among the most committed interpreters of Jelinek’s works, decided to stage ‘The Merchant’s Contracts’ for the audience in a reading – performance format, without shortening any of it at all. Moreover, when in spring 2009 Jelinek set to a continuation of her text under the new circumstances, these extensions and additions were also integrated into the performance previously created. It is true, foreseeing that the unmitigated flow of text may become unbearable, at the commencement of the performance the director warns the public that the coming performance will be four hours long, without any interval, but that the door will be open throughout, so that each person may give themselves a break from this textual attack whenever they wish. The reading performance itself didn’t consist of just a bare microphone and a solitary reader with a sheaf of pages in their hands. Onstage, ruined pensioners materialized, sitting on a couch, groups of choruses shouted at each other, video was employed, the speculators’ magic tricks were played out on the public, and washing over it all was a stream of minimalist music from Erik Satie to Michael Nyman, musical rhythm free of meaning, relaying Jelinek’s monstrous stack of words: a big fat nothing. | |

The theatre project 'Riesenbutzbach' by Christoph Marthaler and Anna Viebrock. Katja Kolm. Publicity photo | |

| With the Theatretreffen performances speaking as if with one voice of our current common situation, which affects each and every one of us, independently of whether we lost something through the banks or never had anything to invest in the first place, intonations completely unexpected for German theatre were manifested in the more usual conversational sounds – for example, emotionality in combination with the warmth of the heart as the core of the message. One such work worthy of notice was ‘Little person – what now?’ brought by Munich’s Kammerspiele and directed by Belgian director Luka Perceval, and based on the Hans Fallada novel which was written during the 20th century world economic crisis. This is a theatre company which has constantly positioned itself as a challenger to the intellect of the viewer, as a stimulator of thought and interpreter of the most complex theatrical texts. This time it presented a theatre story with a narrative that was extremely clear and simple to follow: about the feelings of one young family caught in the reality of growing financial hopelessness. This was done not with an interest in the destructive side of the story – what happens to people enduring long-term poverty – but rather placing the emphasis on a powerful message of confirmation: people are a source of strength, peace and happiness to each other. And not ‘can be’, but ‘are’. Such simple human and emotionally uplifting dialogues from this theatre, or even from German language theatre generally, were unexpected. But the rapturous response of the audience, with extended standing ovations, with the public rising to its feet and applauding at length after the performance of ‘Little person – what now?’, is evidence that for those who follow theatre, exactly these kinds of conversations at the moment are possibly even more necessary than intellectual disputes, mind games, and exploration of the possibilities of form which Theatertreffen has perennially offered. Another great consoler is the Swiss theatre genius Christoph Marthaler, resident in Paris, who has constantly taken the “little person” under his protection. In his performances he takes an interest in those who cannot cope with life, who have fallen or been cast aside. He also felt the “short circuits” of the increasing pace of life a long time before the global emergency struck. Marthaler’s theatrical work ‘Groundings’ was created at the beginning of the new millennium when national airline Swiss Air, as one of the first, went bankrupt. Marthaler caught the approaching slow-down: in the performance, passengers waiting for their plane were initially informed that their plane would be delayed by two seconds, then – by five minutes, then – by twelve hours, then – by twenty five years. The title of Marthaler’s theatre project ‘Riesenbutzbach’, can be deciphered as a major impasse. Butzbach is a small German town. The name of it was once played upon by the Austrian playwright Thomas Bernhard in his play ‘Theatre Master’, in which a doomed-to-failure attempt to put on a play, ‘History’s Wheel’, takes place in a God-for-saken little town called Utzbach. “Utzbach is like Butzbach” – from this the ‘Butzbach’ concept has entered into theatre circle vernacular as a synonym for impasse and the failure of intended action. ‘Riesen-butzbach’ describes the global situation and is itself a global player – immediately after the premiere in Vienna, half the world was standing in line to get this theatre project. Prior to the performance of ‘Riesen-butzbach’ in Berlin, it was shown at the Naples, Athens, Avignon, Wroclaw and Chur international theatre festivals, but this autumn the work will travel to Tokyo’s international theatre festival. | |

The theatre project 'Riesenbutzbach' by Christoph Marthaler and Anna Viebrock. Jurg Kienberger. Publicity photo | |

| Marthaler himself calls the performances “theatre projects”. These haven’t been created on the base of some existing play or opera, but are developed together with the actors in the course of rehearsals. Marthaler began working in the theatre as a composer, providing music for other directors’ performances for about ten years, until once, invited to create a performance himself, he created something up till now unseen and completely different in European theatre – singing theatre, in which time stands still and people wait. Marthaler shapes his performances like a composer, creating a musical score from the various elements of theatre which develop during the rehearsal process and involving actors, musicians, the artist, the playwright and the director equally actively and on even par. In describing his way of working Marthaler tends to borrow comparisons from the world of jazz, likening the creation of his performances to a jam session, a previously unrehearsed, spontaneous improvisation by a number of musicians, as a result of which a musical score is created for the performance. In the final stages of rehearsals, the developed material is given form, with the director constructing the composition of the performance from separate blocks of acting. Work on the performance evolves not from some defined concept, but through the ebb and flow of thoughts around basic ideas and visual images, and the search for acoustic characters, in which all artists are involved. About two thirds of the time at rehearsals passes singing together. In this way performance participants not only get onto the same wavelength, but the possibility of any hierarchy developing is also eliminated. The actors themselves admit that when they are singing together, it’s no longer important who plays a greater or lesser role in the performance, as everyone is united. By singing together for a long time, a collective rhythmic essence develops and the soul of the performance is born. For Marthaler’s performances this is important: they are always performances with soul. Work, for Christoph Marthaler, is time well spent together. In the corner of the rehearsal hall there’s always a table laden with food and drink, where in the periods between singing people can eat something tasty. At times rehearsals take place outside, for example, setting a table on the banks of a river. In the evenings there are no rehearsals in the theatre, and the work continues in a different form. “I don’t always head home after rehearsals to reflect on what, out of all that we rehearsed, was real. I may have also done that, but it’s not obligatory. More likely, we all go and eat together. And during the meal we often solve problems which have arisen during rehearsals. To me that is beautiful.” To describe the processes of performance creation, Marthaler readily borrows descriptions from viticulture: “during rehearsal the performance matures like wine”. ‘Fermentation Process Institute’ – says the signboard above the ‘Riesenbutzbach’ space, which consists of three garages, an office in a glassed-in box, a bank counter with a clerk at the microphone and a balcony with a huge street lighting globe. Real life, as can be surmised, takes place specifically in garages. We see the celebrations of life, celebrated by life’s losers, as the roller doors of the garages open: people are dancing there, and singing along to the Bee Gees hit Staying Alive. This goes quiet as the doors close, and then there is silence, all that can be heard are the ravens crowing as they fly overhead. “I’ve lost everything” – so says an ordinary person. “This isn’t a lost and found office” – replies the bank employee, in a business-like manner. The few possessions – shabby little tables, old, worn chairs, a wooden teddy bear sculpture with a machine gun in its hands and a cartridge-belt around its waist – are lovingly caressed for the last time, before the items are given up for auction and taken away. The singing people, stuck in time and space – in blocked off, closed spaces, in dead-end situations: in the new global crisis situation this special theatre form developed by Marthaler at the conclusion of the 20th century becomes a strange embodiment of hope and optimism. The huge fashion parade which Marthaler organizes at the conclusion of the performance does not radiate ‘glamour’, but ‘the world’s sorrow’. Energetically the “little people” emerge from the depths of the stage, but on nearing the audience, grow scared and quickly retreat. And still, among Marthaler’s fashion models – the losers – some kind of fundamental apathy goes hand in hand with an unshakeable self respect. And the people’s souls continue to sing. /Translator into English: Uldis Brūns/ | |

| go back | |