|

|

| The Visualiser of Invisible Processes Stella Pelše, Art Historian Collection of the projected Contemporary Art Museum: Genādijs Suhanovs | |

| Graphic artist Genādijs Suhanovs (1946–2005) does not belong to the circle of best-known luminaries of Latvia’s art scene; the inclusion of his works into the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art also provokes a question – are we in this case confronted with an example of non-conformism, bordering on dissident opposition to the Soviet system? The general information does not provide instant proof for such conjecture. Suhanovs studied at the Krasnodar Art School (1963–1968), where he obtained the qualification of artist-interior designer. He came to Latvia in 1973, but from 1969 onwards he regularly took part in group exhibitions (over 150 in total), both in Latvia and abroad. Since the late 1970s the artist has held nine solo exhibitions in Riga, one in Berlin and three in Toronto. | |

Genādijs Suhanovs. Object No.3. From Silver Deposit. Mixed media on paper. 32x41cm. 1986 | |

| In 2008 the people of Riga had an opportunity to view the artist’s two memorial exhibitions – the show Debesu bruņurupuči (‘Heavenly Turtles’) at the National Art Museum of Latvia, in the Small Hall, and an exhibition entitled Pasaules pilsonis Nr. 89532 (‘World Citizen No 89532’) on Andrejsala, in the ‘Komutators’ workshop. Suhanovs worked with colour lithography, as well as graphic design, water colours and porcelain painting. Nevertheless it is significant that information about this artist is scant; the basic facts are provided by the encyclopaedia ‘Biographies in Art and Architecture’, Volume 3, and there are also some bits in periodicals and the virtual space. One of the tasks of the Museum of Contemporary Art surely must be to bring out these unjustly forgotten art treasures which have ‘fallen through the sieve’ of official canons, deliberately or unintentionally ‘excluded’ from cultural consciousness. Undeniably, working on the periphery of artistic life without the advantages of official recognition could derive from a romantic paradigm of the ‘artist-outsider’, which includes disregard for a ‘properly’ structured life and art as the only purpose of existence. Even physically looking very much like the legendary pre-war barefoot artist, Voldemārs Irbe, during the latter part of his life Suhanovs became known among Riga’s artistic circles as an integral element(1) of the bohemian crowd based in the M6 café, and a member of the universal artists’ association Zaļais pūķis (‘The Green Dragon’).(2) | |

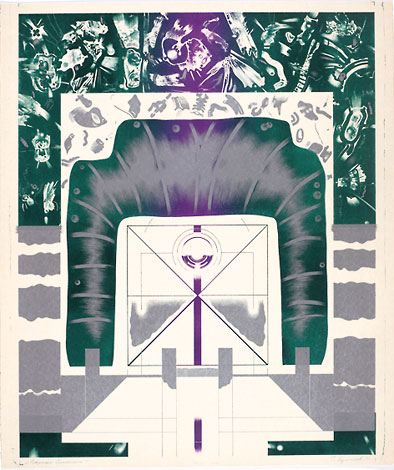

Genādijs Suhanovs. The Gates of Biofield. Colour litograph on paper. 51x37,5cm. 1976 | |

| Nevertheless a life story, however colourful, out of the ordinary or dramatic it may be, is not in itself a museum value. What is it that we find in Suhanovs’ works which may well be classified under the term of ‘easel graphic art’, favoured in the Soviet era, but in which the experts have obviously noticed a certain courage of narrative and investigative spirit differing from the mainstream of the period? His experimental approach to lithography, applying ink washes, pencils of different hardness, a pen, a draughtsman’ s pen, the addition of gold and silver pigment and other methods, certainly deserves attention. “In his works, there is a fusion and layers of information and symbols. Gena was an interpreter of signs, also a prophet, in whose works there flashed an ageless brilliance which will be recognised as truth and honoured as such by future generations.”(3) This role of the artist as prophet was identified by a group of young people who were carried away by Suhanovs’ works and personality. The artist himself, too, is said to have loved to talk about his art, not suffering unduly from excessive modesty: “I am competent in the complete history of art. For me all things are in their right places. The Renaissance is in its own place, the Baroque, the Chinese, all in their places… Yes, and I in my own place. In my art there is a little bit of everything. In my time, I was carried away by cubism, abstractionism, geometrical minimalism, the avantgarde. Sometimes I paint rather naturalistic works.”(4) These kinds of statements by artists, as we know, are not the ultimate truth for the interpretation of their works, but they still provide a certain insight. The capacity to absorb a huge amount of the most varied impressions is undeniable. In the totality of Suhanovs’ works one can find a distinctly postmodernist play upon and transformation of citations, where the sources of inspiration have been masterpieces of the Old Masters (for example, Transplantācija 1 (‘Transplantation 1’), 1977; Botičelli portrets, ļoti strīdīgs (‘Boticelli’s Portrait, Very Controversial’), 1979, in the Swedbank collection of art). Other works from the collection of the Contemporary Art Museum, on the other hand, seemingly imitate the precise spare method of the technical drafting of conceptualism, creating something like maps, charts, diagrams and plans of mystical secret facilities: Objekts M5:1. No Bronzas depozīta. Variants (‘Object M5:1. From Bronze Deposit. Version’), 1980; Kustīgais trijstūris (‘Mobile Triangle’), 1990; or imitate the bilateral symmetry of the Rorschach test as applied in the psychology of perception (Figūra (‘Figure’), 1978). | |

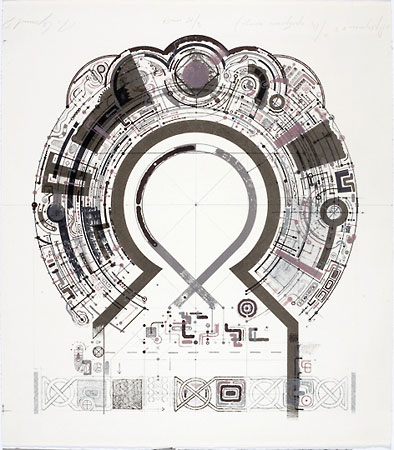

Genādijs Suhanovs. Object No.2. From Silver Deposit. Colour litograph on paper. 45x45cm. 1975 | |

| The works on display this time have a pronounced eso¬teric character, which, as we know, during the later Soviet period constituted a growing counter-current to the official cult of the omnipotence of science, and during the collapse of the regime blossomed into a glorious mix of religiousness, mysticism and magic occultism. On the other hand, the return to the roots, an interest in the lost wisdom of ancient times that are (potentially) encrypted in the ethnographic heritage of various nations (ornamental signs, etc.) was partly to be brought into line also as a component of the official ‘ethnicity’. The genesis for this interest, however, is definitely to be traced as far back as the infatuation with primitivism by the late 19th and early 20th century modernists. The conglomerate of modernist impulses is built like an assemblage of abstract, geometrical and amorphous, irregular elements in enigmatic contexts. Biolauka vārti (‘The Gates of Biofield’, 1976) stand out with a stable composition based on square shapes and diagonals, in which the precision of lines typical of technical drawing can be perceived. The central drive is to make visible the invisible (the Swiss artist Paul Klee, who was an avid user of enigmatic signs and hieroglyphs, wrote in ‘The Creative Credo’ published in 1920: “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible”), namely, objects and processes which do not have really strong scientific proof, but are validated by a vast range of real or imagined experiences and observations. Enerģētiskā fibula (‘The Energy Fibula’, 1981), in turn, features dense masses of circular shapes, intertwined by the geometric precision of a compass, overlapping layers of lines and planes reminiscent of the mandalas of Eastern cultures. The title refers also to the spiral-plate fibulas [brooches] of the Bronze Age as the most direct link to reality. The forms are not symmetrical, but the level of their complexity and precise execution involuntarily associate with the discovery of a miracle of precision mechanics. In contrast to his image as a bohemian, Suhanovs’ works by no means merely capture spontaneous impulses or visions, they are linked by a quasi-scientific enthusiasm for exactitude in which the artist voluntarily assumes the role of engineer – technical draughtsman, with the aim of creating something unprecedented. (1) Daģis, G. Visi mākslinieki ir dzērāji: Vakariņas ar Genu (‘All Artists Are Drunks: Dinner with Gens’) Rīgas Laiks, May 1999, p. 65. (2) The name of the ‘association’ relates to a funny exam story circulating among art historians. An early 20th century group of the trailblazers of modernism called ‘Zaļā puķe’ (‘The Green Flower’) was once, in a student’s answer, transformed into ‘Zaļais pūķis’ (‘The Green Dragon’), a metaphor for strong alcoholic spirits, to which lecturer Aija Brasliņa, as the story goes, replied that this was more likely to be a universal artists’ union. – From a conversation with Brasliņa at the turn of the 20th- 21st cent. (3) Lange, K. Kreilis, D. Pasaules pilsonis jeb aizmirstās nākotnes pēdas. (‘A Citizen of the World or The Forgotten Footprints of the Future’) From: http://andrejsala.lv/33/1500/. (4) Daģis, G. Visi mākslinieki ir dzērāji, (‘All Artists Are Drunks’), p. 65 /Translator into English: Sarmīte Lietuviete/ | |

| go back | |