|

|

| Ephemeral Art Zane Oborenko, Visual Art Theorist Trends in Art Markets | |

| Art markets are characterised by constant change, either in the wake of various types of market speculation or simply following shifts in taste. Commonly this is connected with the popularity of the art of a specific region, market demand for a specific style or period, or the growing fame of a more or less well known artist, but at present a new trend has emerged in addition to the aforementioned: the flourishing of all non-material, ephemeral art forms and rising interest about them in the art market. Whatever the physical form of this art – graffiti, Web art or performance – it is art that must be experienced and valued right now, at this moment, because its existence in time is uncertain and it may be gone tomorrow. | |

NSRD ('Workshop for the Restoration of Unprecendented Feelings'). Walk to Bolderāja. 1987. Photo: Māris Bogustovs | |

| Graffiti and street art are amongst the more approachable forms of ephemeral art. Graffiti has a very long history, already in existence over 30,000 years ago in the form of cave paintings and pictograms made using animal bones and natural pigments, but the presence of graffiti in auction houses and museums is a recent phenomenon. There is such interest in graffiti at auction houses that separate auctions are devoted to it. In 2007, the first auction of graffiti and street art was held by the fine art auctioneers Bonhams. But how on earth is it possible to sell graffiti (which, for most people, is associated with vandalism and tasteless scrawls on building walls, railway carriages and fences) to a society in which the majority is chiefly concerned about how to get rid of it? The most famous street artist active today is the secretive Banksy, who continues to hide his actual identity despite great popularity. His works have been bought by many celebrities and collectors, for example, Jude Law, Christina Aguilera, Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt. In 2007 an anonymous US collector paid a record £288,000 for his Space Girl & Bird, twenty times the estimate. Although the desire to part with considerable sums for works by Banksy fell off sharply after the reduction of liquidity in the contemporary art sector, his success inspired the emergence of other street artists in the UK and France, and paved the way to auction houses and galleries. The street art traditionally sold at auctions and galleries is on canvas, wood, cardboard or metal. It is less common to sell graffiti from walls, and in such cases the price includes the dismantling and transportation of the section of wall. There have also been attempts to sell graffiti which has been executed on city streets and buildings, leaving the winning bidder to deal with the work’s somewhat predictable future fate: either vandalism or being painted over by the authorities. There was an interesting case with a building in Bristol, which Banksy himself had covered with New York-style graffiti. After a number of failed attempts to find a buyer who would preserve the graffiti after buying the property, a radical step was taken in February 2007: the advertisement stated not that the house was for sale, but rather some graffiti by Banksy, with a house thrown in as a bonus. The commercialisation of street art has diminished its unpredictable, unstable nature, and raises the question of whether it can still be considered street art. But such concerns would appear to be unfounded, because what usually separates street art on a canvas, wood or metal surface from any other painting is usually the artist i.e. the persona, painting style and technique associated with street art. A more pertinent question is, does graffiti gain or lose value when it is removed from its original environment? | |

Thomas Lelu. In God We Trust. Painting on wood. 200x130x6cm. 2009 | |

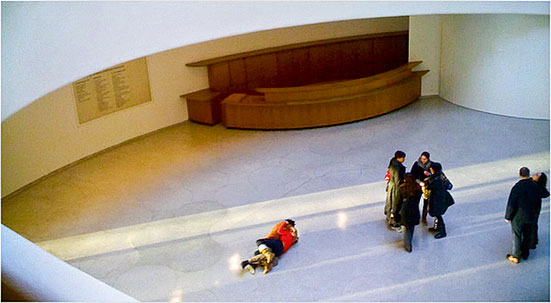

| Graffiti and art similar to it is ephemeral only until the moment it acquires legitimacy or the instant it becomes private property. However, matters are more complex as regards art on the internet, or art that cannot exist without the internet, as it is often characterised by constant transformation independent even of the artist, who only has control over the initial idea for transformation. Caleb Larsen’s sculpture A Tool to Deceive and Slaughter (2009), a 20x20x20 cm black acrylic box, could not exist as an artwork without the internet. The work’s physical form and appearance do not change, but its ephemeral nature lies in the ability to purchase and keep it. By combining Robert Morris’s work The Box with the Sound of Its Own Making (1961) with Jean Baudrillard’s text on art auctions(1), and connecting it to the internet, Larsen has ensured its existence in an eternal flow of transactions. In order for the work to exist, it has to be constantly connected to the internet, except for when this is impossible – such as when it is being transported to exhibitions or to a new owner. A device inside the box checks every ten minutes whether it is in an internet auction. If it is not, the box automatically puts itself up for auction on eBay (2) for one week. If a collector wants to ensure that the sculpture is his or her property for more than a week, they must continue taking part in auctions. Larsen’s work reveals how the art market and collectors are often more obsessed with spending money rather than appreciating the value of a work of art. A Tool to Deceive and Slaughter is a sculpture combined with a specific action which makes it similar to performance, however true performance would involve more action in combination with objects, or in certain cases without them. Originally performance art was created as an art form which cannot be bought or sold, in protest against galleries and the art market system. In recent years it seems to be everywhere, from the collections of major world museums to dinner entertainment for collectors’ clients. In the main, collecting performance art is more about collecting its documentation i.e. photos, video, written documents, preparatory materials etc., rather than the performance itself. The British artist of German descent Tino Sehgal has been the first to really sell the performance itself, rather than what is left afterwards. Sehgal’s works have created an interesting precedent by highlighting the fragile nature of performance. The only place where his works may be stored is the human memory, as any documentation is strictly prohibited. For a work to be regarded as authentic, it is not permitted to have video, photographic or written evidence. This has created radically new challenges for collectors and museum workers in collecting, storing and exhibiting his works, nevertheless it has not hindered the growth of a loyal market for Sehgal’s work. His works have been included in the collections of museums such as the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art, Tate Modern in London, Paris’s Centre Pompidou and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) in New York. Each of his ‘constructed situations’ is sold to 4–6 clients at prices ranging from $70,000 to $145,000 each. Sales are made solely on the basis of verbal agreements made in the presence of a lawyer or public notary, where all the details related to the staging and exhibiting of the work – everything that the artist has intended to give the performance the mark of authenticity, including the persons who will perform it and their training by the artist himself – are agreed upon. | |

Tino Sehgal. The Kiss. 2003 | |

| Sehgal’s living sculpture Kiss (2003), which was inspired by Rodin’s sculpture The Kiss (1889), was bought by MoMa for $70, 000, despite the fact that what it obtained in reality amounted to thin air in material terms. Even more ephemeral than performance and performance collection is the event of creating and collecting ‘something’. A work added to the MoMa Architecture and Design collection on 10 March, 2010, raises major questions and clouds the issue as to what can be considered to be an artwork or design object. This work is the @ symbol, so familiar to all internet users. @ is sufficiently simple and elegant to meet Good Design(3) criteria, but this does not justify its inclusion in a design and art collection. The credit for bringing the @ symbol to the attention of MoMa goes to Raymond Tomlinson, who invented e-mail in 1971. He chose the seldom used @ symbol, which had been on typewriter keyboards since 1885, as a substitute for a long and complicated computer code, thus avoiding the need to replace existing keyboards. What MoMa appreciated was Tomlinson’s act of design, which gave new life to a virtually forgotten sign / symbol. @ first appeared in written documents in the 7th century as a substitute for the Latin preposition ad, while in the 16th century Venetian merchants used it to denote an amphora, which served as a measurement unit of quantity. Later on as well @ retained its commercial nature. In the 19th century it meant at the rate of, but it then gradually lost its role in written communication. Tomlinson promoted the rebirth of something forgotten and turned it into an indispensable and significant component part of the contemporary world, without which modern communication would be impossible. There was much comment about the fact that MoMa included the @ symbol in its collection without going through the usual procurement process. @ was neither purchased, nor were the exclusive rights to use it acquired. @ belongs to everybody and nobody at the same time, and this made it possible to include it in the MoMa collection in this manner. | |

Lukasz Jastrubczak. Eclipse. Performance. 2010 | |

| These are just a few examples of the growing trend for enjoying and collecting ephemeral art forms. These changes are gradually entering the public consciousness also through the environment and the space in which we live. The sharp divide between art, design objects and architecture is increasingly eroding; the classic relationship between the object and functionality in designed objects is gradually being lost and the focus is on providing an emotional experience. The desire for the ethereal and ephemeral has always been a feature of life in financially difficult times. In 1929 photographic art became especially popular; later, in the 1970s, it was joined by performance and since 2008 we can add to them the new ephemeral art forms. On the one hand, this is indicative of a desire to continue collecting and creating art even on limited means, seeking alternative outlets for creativity, but on the other hand, it indicates a desire to enjoy what is the main prerogative of art: an emotional and intellectual journey expressed through personal experience. It is a desire for a world free from the cult of materialism, where ideas are the most important thing rather than the gilded frame and its size, where the ephemeral and unrepeatable is appreciated as symbolising the ephemeral and unrepeatable nature of life itself. (1) Baudrillard, Jean. Pour une critique de l’economie politique du signe. Paris: Galimard, 1972; Baudrillard, Jean. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (Chapter 5: The Art Auction: Sign Exchange and Sumptuary Value).Transl. Charls Levin. Saint Louis: Mo. Telos Press, 1981. (2) http://atooltodeceiveandslaughter.com. (3) Good Design is a MoMa concept born in the 1930s which became especially important after World War II (1945–1956). /Translator into English: Filips Birzulis/ | |

| go back | |