|

|

| Save As? Raitis šmits, Artist and curator Rasa šmite, Artist and curator Media art – from source code to stage production | |

| “I think that we can only genuinely reflect our time when we use the means from our time.” (Georges Seurat) Imagine the end of the 21st century! you’ve just returned from london, where at the tate gallery you’ve viewed a nam June Paik videoinstallation created about a hundred years previously, and now you’re flying to new york to see how this famous 20th century media artist’s works are exhibited at the whitney museum and the guggenheim. on the way, you decide to visit the zkm centre for art and media museum at karlsruhe in germany, because it’s just starting to get interesting now... at the first venue, the display reminds you more of a museum of archaeology – there are old television valves, drawings and descriptions set out in glass cases, and a small fragment – a television tube with the rainbow colour field left by a magnet – evidence of a once functioning video-installation. a century-old sculpture made from a stack of television sets, of which only a few are still operating, is also impressive. meanwhile at the next place there’s a surprise: in some holographic projections you can view a functioning tV buddha, though the colours are a little too bright. and finally, at 8pm you attend a staging of Paik’s satellite performance which once took place... What does this mean? that media art works can be interpreted for exhibiting in different ways and the issue of the authenticity of a work of art in media art and in the traditional media, taking into account the relentless development of digital technologies, the possibility of copying and duplicating, must be regarded differently. the curators of the future have become directors of exhibitions. media art works are being staged according to the scenarios devised by museum curators. The ZKM centre for art and media director Peter weibel, well-known media artist and curator, explains that unlike painting, where the genuineness of the work to be viewed is always emphasized, “we could maintain the opposite, that there isn’t a real Mona lisa, because various interpretations exist. in nam June Paik’s case then, it could be a work that consists of hardware alone and won’t work. you’ll be able to view this work of art in operation at twenty other sites. i like this type of future (..) media art differs from painting, to a fairly large degree it is even the opposite. it gives the freedom which theatre and opera have already.”1 The issue of the authenticity of a work of art in the theatre is solved differently than in painting. today, authentic shakespeare could even look a little eccentric, even though, of course, there would be people interested in watching it. or, as weibel says: “theatre succeeds in creating an illusion almost worthy of a magician’s art, making people believe that it’s shakespeare, even if only sixty percent of the text is original”. even when the original shakespeare scenario is used, a new image, different costumes and different stage design is created for each production, and yet “people still recognize it as shakespeare, due to the text and concept” 2. In any case theatre and opera reveal to us that anything can be played and staged repeatedly. even when shortening the five-hour Rienzi to two hours, we can still recognize wagner, regardless. we will never see Rienzi in the way that it was staged in the opera houses of europe in the late 19th century. though the story, the libretto and the music itself may not change, the means of expression of the production change with the times. in a new production this year in riga, the laser drawings used and the electronic musical accompaniment composed anew for the scene with the ballerinas offer a very creative example of reinterpretation. we’ve already got used to interpretations, even as radical as this, and they seem acceptable to us, but why couldn’t this approach be adopted in contemporary media art as well? weibel explains this with the art market, where the price is undoubtedly higher if there’s a unique, one and only original, even if often enough this is an illusion, and also with the conservatism of the art sector, which comes about because it’s customary that the heads of arts institutions most often are not artists – they are usually art historians. it’s not like that in other fields: a mathematics institute will most likely be headed by a mathematician, not a researcher of mathematics history. “the arts sector (not the artist) along with museums and collectors is becoming very conservative, as we are holding on to the idea of the original work of art. a certain ontological conspiracy is dominating the art world along with the desire to hang onto one singular object, but in the case of media, this won’t be possible.”3. | |

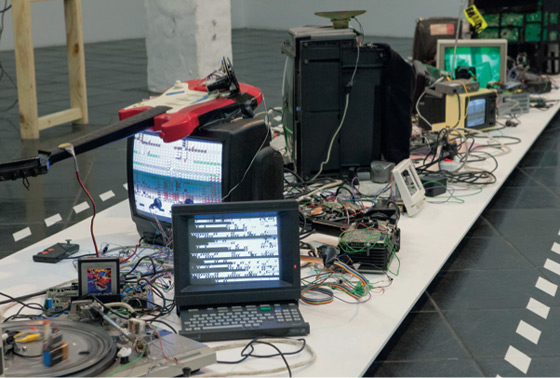

Benjamin Gaulon, Karl Klomp, Gijs Gieskes, Tom Verbruggen. Refunct Media. 2010 Publicity photos Courtesy of the artists and RiXC | |

| Therefore, according to the future scenario, it’s possible that in the case of media art there won’t be just one single original work, but a number of interpretations of a work will exist, which, depending on who is doing the interpretation, will be more or less successful. that, of course, could seriously affect the current art market which is still quite reserved in its attitude toward the purchase of media art works. and yet art Basel Miami has begun to voice the idea of New Media – New Market. despite such trends, we still cannot know what the strategy for the preservation and exhibition of art works will be like after 50 or 100 years. what exactly should we be preserving from new media art? the description of the idea for the work of art? a plan of the exhibition scenography? all of the parts, the old equipment – even if, after a while, it doesn’t work any more ? New media art works can be described as a body of programming codes combined with specific equipment. for example, media archaeologist erkki huhtamo’s view is that the work of art definitely has to work4, contrary to the previously mentioned idea from weibel, that a work not in operation can also be exhibited. in both cases, an important role in the preservation of the art work is played by the maintenance of structured documentation. in our view (there are other artists who think so too), in media art works the social context is often important, but how can that be preserved? web art, for example, which was initially created for viewing only on the internet, and in which dynamically changing data on the internet is often used, has to be preserved in accordance with the specific character of new media art - changing the traditional approach to preservation. according to weibel, a museum is like a noah’s ark in which art values are statically saved, in contrast to the concept of music as an open, dynamically changing structure.5 whereas new media art is an example, in the most explicit way, of the malraux metaphor about the “museum without walls”6. even the issue of the audience. collectors and museums can’t buy the viewer, who in new media art is often a collaborator as opposed to contemporary abstract, conceptual and object art. weibel explains that “that’s the reason why so many critics and art restorers and even artists disavow participation art, which is one of the primary elements in media art. you can’t be a participative sculptor or painter. only with digital art and especially, in media art, does the opportunity arise to become an active, participative public.”7 we can see how distanced the viewer is from traditional art in the case of the Mona lisa in the louvre, where the viewer is being moved increasingly further away from the original work, locked in its glass case and enclosed by a little fence, and only allowed to admire from far away. modern art, which created its own reality and also the viewer as a real person who could be involved in, for example, actions and performances, declined to take the viewer seriously, however, as a result of pressure from the art market. the position of new media art, in contrast, is that a work of art doesn’t exist if interaction with the viewer doesn’t take place. “this was a step, far too bold for modern art, with its dominant ontological conspiracy, to accept. it could accept that the viewer could look at the work of art and do something with it, but it couldn’t accept that the viewer becomes very significant to the work of art itself and that the attention suddenly switches from the art work to the viewer.”8 that’s why the question of the audience in the preservation of new media art is taken seriously. The exhibition SaVe aS or Saglabāt kā was created so that new media art preservation issues could be explored, exposed and analysed in practice. this was a challenge not only because one of the authors of this article used this as an innovative – practice-based – research method in his doctoral research at the latvian academy of art, but also because it was produced in connection with the wide scope art history conference, Media art Histories 2013, which was organized by our rixc centre for new media culture in collaboration with the riga school of economics, the art academy, the liepaja university art research laboratory and the krems center for image science (austria). the opening of SaVe aS was attended by nearly all 200 participants – art historians, theorists, historians, curators, conservators (restorers) and academic researchers from many influential art institutions including the guggenheim and whitney museums, the tate, zagreb museum, goldsmiths and countless other universities, art centres and museums from all over the world. The main idea behind SaVe aS (at kim? contemporary art centre, 9 october – 17 november, 2013) was to show various approaches to the preservation and exhibition of new media art works, not in order to provide ready answers, but instead to pose questions. there were 16 art works on show in the exhibition, the authors being internet art (net.art) pioneers: jODi, olja ljalina, heath bunting, alexei shulgin and e-lab / rixc, as well as slightly younger generation artists who have already gained wide international recognition, evan roth and aram bartholl, and emerging young artists artis kuprišs and andris Vētra, and in addition media artists’ collectives such as Refunct Media and net.art.database, all of whom are concerned with the preservation of new media art works. In preserving new media art today, a number of strategies are used. the first is a time capsule, where the art work gets preserved together with its original technology. the second is the migration strategy, which provides for regular adaptation of the work to changing times with the relevant new technology. the third – an emulation strategy – has been adapted from the computer industry and is intended to ensure the authenticity of the art work, using special emulation software to operate an obsolete code on the latest platforms. and finally, the fourth and most radical of the strategies – the work reinterpretation strategy, which, similarly as in the art of the stage, provides for a new interpretation every time the work is exhibited. All of the strategies mentioned were used in the SaVe aS exhibition, both individually as well as in mixed form. we’d like to look at the SaVe aS works from three different perspectives. in the first group there are works which directly show the most significant aspects of the preservation of new media art. in the second – works, which reference the social context and internet era “clichés”, or the mass visual culture on the internet which could be termed “digital folklore”. in the third group there are works which self-reference the media era and its problems. The first that we’d like to start with is the work of the internet avant-garde or internet art pioneers jODi. this has been selected as an example of a radical position as regards preservation, holding that the main thing is to maintain only the most essential parts of the work, namely – as in this case – the source code. The title of the work OSS/**** (1999) is an abbreviation of the concept “operational system” and encapsulates one of the most significant characteristics of new media art works: basically the work itself can be the code .the code as such isn’t difficult to maintain. but the problem is caused by the fact that this code operates only in the relevant environment, in the operational systems of the late 1990s: Windows 95 or Windows 98 and Mac OS9. the OSS subversive operational systems were created by a pair of artists from the netherlands and belgium, Joan heemskerk and dirk Paesmans. known as jODi, they are among the most famous of the early generation of internet artists, also having studied under nam June Paik. jODi’s artistic mission is to create a new type of information technology aesthetic, overturning generally accepted views about computers, computer systems and computer software, computer networks and even computer games. you can experience this on the artists’ homepage jodi.org, which will open up with a different work of art by the authors each time. on putting the OSS cd-rom created by jODi into your computer, unusual things begin to happen. windows begin to open up, one after the other, filling up your screen and disrupting the initial intent. as soon as you start to move your mouse, it begins to draw black, grey and white joined up lines. it will all become even more complex if you start using the keyboard – the visual appearance of your computer desktop will also undergo change, there will be all kinds of sounds and texts of varying size will appear, which together with the numerous previously opened windows will move in a strobe-like rhythm, creating a completely new insight as to what your computer can do. for the exhibition in riga the original cd-roms were used, but as they don’t work in the more recent environments, we used the emulation strategy as the main one, installing the old Windows 95 / 98 operational system on the new contemporary Windows 7 platform. A different exhibition strategy – reinterpretation - was also used for a work of a different nature, Xchange, internet radio network (1997). harking back to when the internet came into latvia more than 15 years ago, the work Xchange manifests the creative searches by the latvian internet art pioneer e-lab and rixc founder, and author of this article, at the time when, after the collapse of the soviet union, opportunities for free expression and a new free space, namely the internet, finally opened up for us young artists to express ourselves. at the exhibition there was a staging of the operation of one of the first internet radio studios which began broadcasting from riga in the late 1990s, which through its own initiative created the centre and main connection in the Xchange creative internet radio network. we regularly met up with the participants of this network in the expanses of cyberspace, to experiment together with live broadcasting possibilities and creating wandering sound loops. the participants came from the most diverse spots on the globe with a variety of time zones, like europe, canada and australia, and it was a great challenge to coordinate meetings with them, both in time as well as technically. in the improvised Xchange studio, exhibition visitors could themselves find out about how these famous Xchange loops were created, speaking into the microphone and listening to how, after about a minute, having travelled through internet servers and connections it had become overlaid with the noise of electronic technologies and layers of sound before returning to the studio. | |

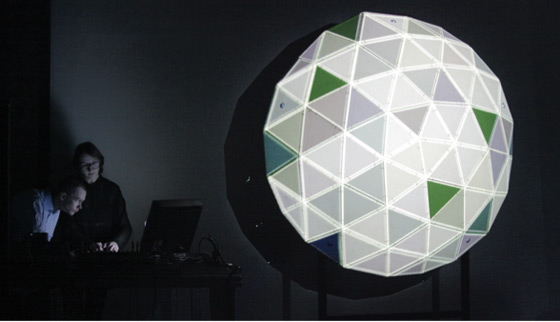

Irīna Špičaka, Krišjānis Rijnieks, Platons Buravickis. Metasphere. Performance. 2013 Publicity photos Courtesy of the artists and RiXC | |

| As there is no code at the basis of Xchange, but rather improvised sound material and people who broadcast it, it is an example of the second of the more radical positions on preservation which encourages the preservation of everything possible, including documentation of the work. if none such was created at the actual time of the event, then the documentation of other later interpretations and stagings is permitted. Internet art works such as this, where the form of expression is a code or participation in a direct broadcast, and which additionally are only accessible in the environment of their time, are truly fragile. how to make them sustainable, or at least accessible today and in the near future? today only a few museums are trying to solve this question and that is why the artists themselves are also trying to prevent the disappearance of early web art. two artists from germany, robert sakrowski and constant dullaart are the initiators of the net. artdatabase.org project in which web art works have been collected and documented since 2011. the artists’ methodology has been based on a subjective interpretation and approach. referring back to weibel, the maximum amount of possible data truly is being preserved here. in the documentation of the work, along with the demonstration of the specific art work, various contextual elements also are recorded: the humming of electricity, sounds given off by hard discs, monitor clicks, sighs which can usually be heard in periods of waiting, going for coffee etc., all of which, according to the opinion of the project authors, are just as important as code archiving and the creation of “metadata” (descriptions of works). the documentation of the works is immediately placed on youtube, so as to make it accessible to everyone on the internet. Well-known german artist aram bartholl, on the other hand, has actualised the preservation of web art works from the aspect of exhibiting. at the exhibition, bartholl created On-line Gallery Playset (2012) and invited visitors to the exhibition to cut out small paper models of the gallery space themselves, and to play with them, putting them in front of a computer screen on which you could see various websites in the internet browser window. the work drew a very positive response – countless “galleries” were quickly cut out of paper and folded. at the close of the exhibition, due to the participation of viewers the artwork had taken on a completely different image than it had had at the start. and once again we return to the viewer, who today is possibly more responsive and ready to collaborate than ever before. The next group includes works which reference the development of mass visual culture on the internet, something that exhibition artists olia lialina and dragan espenschied call “digital folklore”. today’s social media platforms with their countless new images placed on them daily by users, the beginnings of which can be found in the film and advertising industries, are an absolute triumph of visual culture. and again – as has happened more than once last century – art is pushed from its pedestal, because creativity and the tools of visual expression were once solely the prerogative of the fine arts. today, the means of modern visual depiction and expression such as photography or film have been made accessible to everyone – since they’ve arrived on your mobile phone. there are tens of billions of the most diverse visual “objects” on the internet. media artists have already been using consumer equipment since the 1960s, when portable video technology evolved. since the 1990s, when internet and personal computers came on the scene, and later – “smart” phones, there’s no longer any differences in the means of production of visual “objects”: they are equally accessible to artists as they are to any person. what then is the difference between an art work on the internet and simple digital photography? what is the socalled artistic touch in technological media? firstly, undoubtedly, it is the idea - the concept of the art work, as well as the context – where the art work gets displayed, where and how it’s shown, how it’s documented, and finally – and this may be the most important – where and how it is discussed, similarly as with other 20th century process art, happenings or actions. at the same time, as pointed out by media archaeologist erkki huhtamo in his lecture at the Media art Histories: ReNeW conference in riga in the autumn of 2013, we cannot ignore this new situation where the masses want to be creative. we cannot pretend that we haven’t noticed all of these billions of photos, videos and animations on the internet which are becoming a kind of digital folklore of the 21st century. huhtamo emphasizes that “we can’t deny these clichés, art historians have to take them into account too, and in addition, more than ever before”.9 Well-known internet art pioneer and web artist olia lialina plays with this “folklore” data. together with dragan espenschied, who calls himself a researcher of “digital folklore”, she had downloaded the entire contents of the early social media Geocities, after the owners of the service declared that they were closing it, giving its users just a few weeks to collect their data. we can only try to imagine what we’d do if someday this happened with draugiem.lv or facebook – we’d probably want to keep our profile, pictures and texts. this is exactly what olia and dragan did – they used the opportunity to get into the Geocities server and downloaded all of the user homepages from the earliest period of the free service. it took them many weeks. but as they are artists and did it in the name of art, then, on the one hand, a large period of the 1990s has now been preserved, a time when the most avant-garde expressions of Media art emerged – art on the internet. on the other hand, such an impressive action in itself has already become a work of art, due to the way the project authors have presented it: by talking and writing about it and publishing this achievement as an act of art. However, it was another “digital folklore” work by the two authors, Once upon (2011–2012) that was exhibited in the SaVe aS exhibition. this is olia’s and dragan’s interpretation of today’s social media and internet services, which have been transferred to the aesthetic and spirit of the internet of the 1990s. to check out how the work functions in full, visit 1x-upon.com/, and you’ll be able to see what google, facebook and youtube would look like if they’d been created in quite recent 1997. lialina’s latest work Summer (2013), in real spirit of the 1990s aesthetic, was also on display in the exhibition. the work was created very recently when the artist, while surfing the internet, noticed that her internet art works had substantially changed due to improvements in the speed of the internet. Well-known american artist evan roth, resident in Paris, is from a slightly younger generation of web artists. in his work a Tribute to Heather (2013) he used animation from the non-commercial internet archive Heather’s animations. this archive is a private initiative that makes available various early 1990s gif images, and is still operating due to its impersonal name. Heather’s animations, like the corporate Geocities, has been in existence since the 1990s and has maintained characteristics typical of the earliest internet pages. the archive has managed to avoid the problems of authorship and copyright – to every visitor it offers thousands of images to download, free of charge. roth had selected some of the most interesting moving gif animations and reinterpreted them into his artwork. Another pioneer of internet art, alexei shulgin, is an artist from moscow who became famous for a photo-gallery of russian artists, created in 1994. with this he protested against contemporary art curatorial practice in which there isn’t a single objective criterion for selecting or rejecting artists. shulgin works in a much more ironic way with the dominant of visual culture. together with aristarkh chernyshev they showed at the SaVe aS exhibition an automatic art creation machine. the work artomat (2011) offers an automated system in which you can select an object, using certain methods, then join it to another object, put it in a suitable place, and your unique work of art work is ready! the operation of artomat is based on previously determined algorithms which generate art in an automatic or semi-automatic way. every viewer can create works of art according to their own taste and wishes. in combination with a 2d or 3d printer, artomat facilitates the creation of pictures and sculptures, thus automating the whole process of creation for works of art – from the concept to its realization. a work of art like this is also really useful in preserving art, taking the path where the authenticity of the work has lost its meaning with the development of the practice of re-interpretation. Finally – the third group, which illustrates and self-references the media with which it works. most of all this was expressed in the works of french artist benjamin gaulon and the joint work Refunct Media (2010) by dutch artists karl klomp, gijs gieskes and tom Verbruggen. Refunct Media is a multimedia installation in which obsolete digital and analogue media players and receivers are used for a second time. for the creation of the work in riga, residents donated old television sets which the artists dismantled and reconfigured, joining them up into a large and complex system of elements. the authors of the installation are united by an investigative interest in obsolete media technology and its relationship with biological systems in nature. the authors showed us that equipment, like biological organisms, have their limited lifespan and don’t function forever. each little motor has its finite number of revolutions after which it stops. the impressive installation set up at the exhibition initially roared and buzzed, but gradually ceased to work, in this way encouraging reflections of an ecological nature about the similarities and differences in biology and technology. The behaviour of technology has also been reflected in the works of american digital artist, Parag kumar mital, where he researches models of human audiovisual perception. in the work YouTube Destruction (2012), the artist mixed and synthesized the weekly youtube top 10 videos to create a new video. the video which was in first place was mixed with the other nine. the goal was to keep doing this each week, for as long as it took, until one of these videos made it onto the youtube top 10 list. however, after five weeks mital received a complaint about a breach of copyright which was based on the fact that he was using the contents of the top 10 first place-winning video. the artist’s video clips were denied access. in order to renew his account, he had to watch an animated clip about the law on copyright and take a test on his knowledge of copyright. later, mital created a synthesis about this video as well. it’s quite possible that the notices of complaint came automatically from the youtube service which is responsible for the contents and copyright protection. the artist challenged the youtube ruling by proving that he had not breached copyright, and his works were once again restored to the youtube community. The question of copyright in the internet environment has not yet been completely clarified, as it’s not unusual that new media artists want the work they’ve created and its content to be free of copyright restrictions. this issue will become even more complex with the reinterpretation of media art. the young artists andris Vētra and artis kuprišs took part in the exhibition with their project lāčplēsis Technology (2012) which offered two products that they had created. one of them was lt-ml002 – a pirated music legalization computer programme. it starts to work automatically, as soon as a memory stick is connected to a computer. the programme breaks up the mP3 files on the memory stick into tiny parts and by lining them up in random order creates new – unique compositions with your favourite sounds. whereas lt-gr002 is an alternative media Player that you can take with you and safely play even the most well- known music in public places, without getting into copyright problems. the basic principle of the player is a mechanically created rumble which has variable playback tempo and amplitude (volume). In conclusion we should add that alongside the web art works at the exhibition there were also photographs on show. this wasn’t a random choice. italian artist lamberto teotino’s One-dimensional Coordinate System (2011) was a metaphoric reflection of the exhibition’s idea about preservation in time and space. the work was made up of a series of images – old photographs from archives, showing technologies from different eras together with their inventors (edison and others). conceptually the photographs had been processed using a reference to a onedimensional coordinate system theorem developed by french philosopher and mathematician rene descartes in the 17th century. the artist had used descartes’ theory to formulate the antithesis between science and the supernatural in new way. with the help of the cartesian axis, a flood of digital data was created in photo images. Visually it looked as if a certain part of the image had disappeared, while all the rest stayed the same – in a similar way as in objective reality the unknown is hidden behind fine, indistinct variations. we are hoping that in the cases of reinterpretation of art works at the SaVe aS exhibition we had been able to find and show some new facets or nuances of the art works exhibited, ones that initially, while these works were in the process of being created, were not perceptible. Right now we are continuing to address media art preservation and exhibition issues in practice and together with media artist, writer and curator armin medosch from austria we are putting together a major international exhibition fields. it will open on 15 may at the arsenāls exhibition hall of the latvian national museum of art as one of the Rīga 2014 programme events. at the exhibition, the issues of preservation, restoration, reinterpretation, and other relevant issues related to sustainability will no longer be limited only to digital art and how it is archived. the fields exhibition will look at the sustainability of contemporary art over a much wider spectrum, where art has become a creative practice that brings together new thinking, a scientific approach, aesthetics, technology and social practices. Translator into English: Uldis Brūns 1 Šmits, raitis. muzejs nevar iegādāties skatītāju. conversation with the director of zkm centre for art and media Peter weibel. Studija, 2013, no. 91, p. 68 2 ibid 3 ibid, p.69 4 Šmits, raitis. kas ir mediju arheoloģija. interview with eric huhtamo. 10.12. 2011 / appendix to raitis Šmits’ thesis (unpublished) 5 weibel, Peter. Web 2.0 and the Museum. grau, oliver (editor) imagery in the 21st century. cambridge and london: the mit Press, 2011, pp. 235-244 6 malraux, andré. The Museum without Walls. in: Psychology of art, Vol.3, 1947 7 Šmits, raitis. muzejs nevar iegādāties skatītāju. Studija, 2013, no. 91, pp. 63 –71 8 ibid 9 huhtamo, eric. “hey you, get off of my cloud” media archaeology as topos study. lecture at the conference Media art Histories 2013: ReNeW in riga, 8 – 11 october, 2013 | |

| go back | |