|

|

| “A meteor flares as it falls” Jānis Borgs, Art Critic Visvaldis Ziediņš and the discovery of his art | |

| The chances of finding a new and unknown island in the Gulf of Riga are close to zero. Almost the same could be said about the likelihood of discovering something new and unknown in the relatively easily overseen field of our art. However, that’s exactly where some quieter and “more overgrown” areas can still be found, where one can still stumble upon unexpected and wonderful art discoveries. This kind of bright occurrence flashed up at the end of the last century, for example, in connection with the surprise discovery of artist Ādolfs Zārdiņš. And now we’ve had similar luck. The artist’s name and extensive creative achievements, if not completely unknown then basically ignored by the wider public up till now, have seen the light of day due to the monumentally comprehensive research work of art historian Ieva Kulakova. His name is Visvaldis Ziediņš (1942–2007), and he is from Liepāja. It should be added that the wisdom and initiative of Liepāja artist Alda Kļaviņa and gallery owner Ivonna Veiherte were also instrumental in the process of his public “re-birth”. The process of appraisal of the artist’s legacy began only after his recent death, when the doors of the master’s studio were opened wider and the collections of works hidden from the public for many long years became accessible to researchers. Appraisal began around 2009, with the crowning achievement now being the opening of the Kustība. Visvaldis Ziediņš (‘Movement. Visvaldis Ziediņš’) exposition at the exhibition hall Arsenāls, as well as the publication of an outstanding monograph on the artist. | |

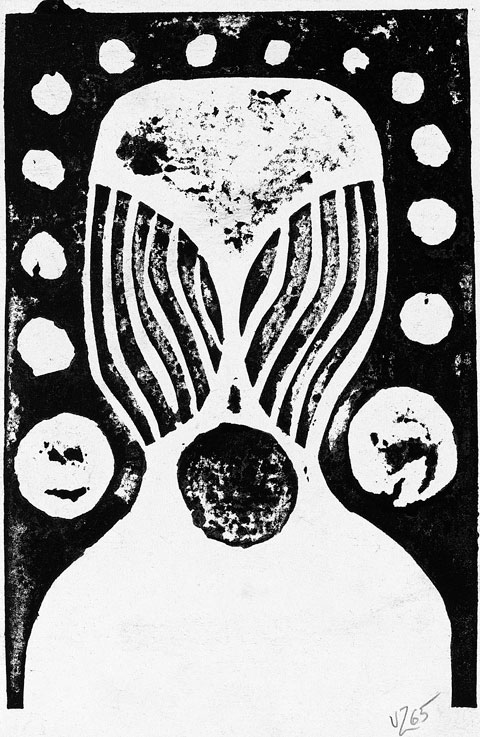

Visvaldis Ziediņš. Alien. Indian ink on paper. 20.2x13.3 cm. 1965 Publicity photo | |

| To fill up Arsenāls on your own is a challenge which can only be met by artists endowed with a volcanic power. After his demise, it was discovered that Visvaldis Ziediņš, too, belonged to this group of powerful achievers. Approximately 3,000 works, seen previously only by the very few, were found at the artist’s studio; a heroic quantity from which curator Ieva Kulakova “filtered” and provided a selection of many hundreds of works for the exhibition. In her selection, she acted almost like a loving mother, ready to show off and boast to others about nearly every creative expression by her child. A deeply scientific motivation and order reigns here, however, revealing not just the developmental dimensions of Ziediņš’ art, but also of his creative personality. The saturation, structure and many layered nature of the exhibition gives the viewer (and especially – one who wants to research) a generous feeling of satiation and satisfaction. In the thematic groups Laika nospiedumi (‘Imprints of Time’), Sajūtu entropija (‘The Entropy of Feelings’), Atbrīvošanās no realitātes (‘Liberation from Reality’), Struktūras (‘Structures’), Jauna pasaule (‘A New World’), Civilizācijas teātris (‘The Theatre of Civilization’) and Kosmoss (‘Outer Space’) we can observe an original and unusual survey of the 20th century modernist panorama – from cubism, Dadaism, abstractionism right up to pop art, installations and Fluxus art expressions. Almost like the resource room of a real modernist academy. There really was something to see, consider, examine and sift through... Visvaldis Ziediņš’ path in the early 1960s took him through education in the Department of Decorative Design at the Liepāja Secondary School of Art. Then, in order to earn his daily bread, all kinds of work in the field of decorative design and theatre scenography followed. As a consequence, he was known more widely as a stage set designer, or as belonging to those whose artistic activities some consider to be second rate, unburdened by the spirituality of “serious” art. Like someone prettying up the environment, increasing beauty... Like an “also-ran” to “great art”... At times one can observe how artists – decorators and display designers – try to aspire to art’s “highest spheres” through their other activities, for example, in painting. But such attempts have often turned into “pelican runs”, with emphatic superficiality or even dilettantish stumblings, without the elevation of real art. This kind of shadow of suspicion could have also been cast over Visvaldis Ziediņš. And it could happen that there may have been some confirmation of this among the sizeable deposits of his works, as every so often the master sifted through his works with a critical eye and destroyed what he considered to be worthless. Unfortunately. However, this exhibition completely dispelled all the previously mentioned concerns and convincingly revealed something else – the Personality and the Thinker, already thriving in his younger years, which is at the core of Visvaldis Ziediņš – the Artist. His “stormy youth” period at the turn of the 1950s–60s (and fruitful development during the 1960s) coincided with a period of ideological thaw in the post-Stalinist Soviet empire. Despite the many restrictions on freedom which were retained, this was a time of great hope and also a time of great delusion. Streams of ideas from the West, previously strictly banned, flooded in through the gaps of the considerably rusty Iron Curtain. It was specifically the favourable conditions of this era, it seems, that unleashed a chain of consequences which significantly influenced the rest of the budding artist’s life – both in the sense of creative productivity, as well as in the evolution of his quite dramatic life. | |

Visvaldis Ziediņš. Horror (Object). Wood, metal and oil. 72x20x24 cm. 1966–1987 Publicity photo | |

| Ziediņš began his unswerving and confident progress along the modernist course surprisingly early – while still in his teenage years, and in a deeply Soviet atmosphere. Looking at it objectively, he far-sightedly knew how to make use of the rare opportunity that had developed with the existing regime’s “approval” – right at the time when the Soviet Union Communist Party Central Committee in distant Moscow had decided to allow some fresh air into the stifling ideological atmosphere of post-Stalinist Soviet Union and quite benevolently permitted such, previously considered dangerously “contra”, cultural laxity. But from a different angle – the local society of the time was still permeated by the inertia of old dogmas and “paralytic cramps” of the Stalin era, and it would have been naïve to expect some sort of more enthusiastic understanding of modernism among the “mass of humanity” after so many years of demonizing everything Western. At art schools also, most things rolled along the well worn tracks for many more years. Perhaps some unfulfilled illusions dwelled within Ziediņš in this respect, and a deep alienation developed in the young artist, like in the existentialist novels and films which at the time were in favour among the intelligentsia. The flourishing of modernism in Latvia began to branch out more profusely only at the end of the 1960s and in the 1970s, and culminated at the time of Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost. But Ziediņš’ creative surge coincided with a real “frost in spring”. In 1963, frightened by the genie of free thinking that had been released from its ideological bottle, the regime began a grotesque anti-modernist, anti-abstractionist, anti-formalist campaign, a fierce tightening of the ideological screws. This didn’t really solve anything, it just strengthened the fermentation and the power of the oppositionary alternative culture which had been pushed off-stage. But for many it also increased depressiveness and an inclination to isolate their internal freedom and spiritual independence from the aggression of the external environment. It was mainly the young people and the intelligentsia, especially the creative ones, living in large Soviet cities who absorbed, carried and disseminated the newly found Western cultural ideas. In this sense, one would think, a fertile ground for any form of dissidence had not yet matured in Liepāja. Visvaldis Ziediņš, just like dozens of others of his contemporaries – young art highflyers felt an allergy towards the archaic canons of social realism, logically associating them with the already declining Soviet reality, in part already dumped on the scrap heap. He was searching for the deepest sources of world culture. This was an unquenchable thirst for free art, slaked in many ways by the previously inaccessible flood of information – mostly in the form of periodicals and books from Western and also the so-called brotherly Socialist nations (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and East Germany). After the previous starvation-diet of ideas, the new situation could be considered a real information boom. The section of society interested in the arts gradually began to master the classics of modernism – from impressionism, through cubism, expressionism, surrealism right up to the abstractionism and pop art which was important at that time. And even the latest avant-garde expressions – Fluxus, conceptualism, happenings, installations... These were really very exclusive delicacies which were enjoyed by a relatively narrow circle of creative intelligentsia gourmands, whereas the roles of the popular heroes of the day for general consumption were filled by Picasso, Chagall, Dali, Leger, Munch... And Ziediņš, thanks to his mental sharpness and activity, was one of the first to this intellectual feasting table. | |

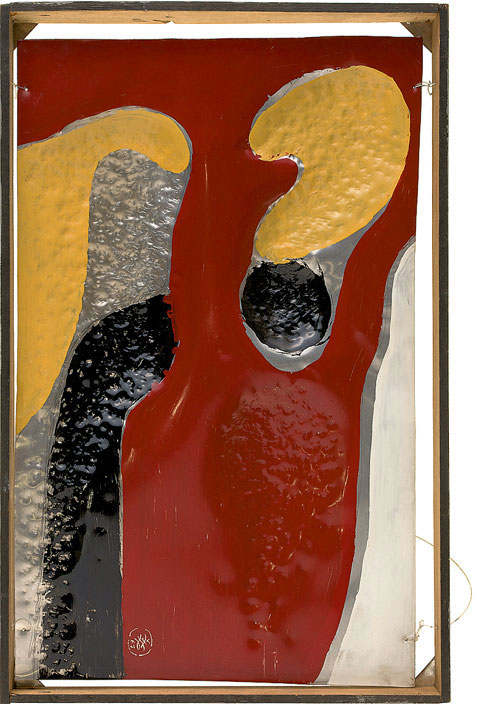

Visvaldis Ziediņš. A Story of Stories Oil on metal sheet. 40x26x5 cm. 1967 Publicity photo | |

| No matter how comical it may seem now – among Soviet society of the 1960s great enthusiasm was generated by Impressionist and Post-Impressionist revelations and paintings by great masters, which were by now almost a century old. New idols appeared in the pantheon of every educated and “chosen” homo sovieticus. At the forefront, with the examples of their life and art, stood out France’s 19th century Impressionist and Post-Impressionist giants such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Cezanne... And from more recent times, the almost obligatory American writer Ernest Hemingway – the bearded strongman in his coarsely knitted jersey. Along with these masters, a template of the new artist type and models of behaviour also became entrenched in people’s consciousness. This was rooted in an anarchistic free-thinker and bohemian lifestyle, where the artist was in sharp conflict with the ever conservative ruling powers, the art institutions it supported, the reactionary academy, classic values and traditions... The artist was misunderstood and ridiculed by both the “people” as well as bourgeois philistine society. Revolutionary ideas were boiling up within the artist. A real artist was extremely poor, rejected, unrecognized, often lonely and abandoned. And with an ear cut off, or having escaped to tropical islands, or at least having succumbed to the embraces of Paris brothels... As we can see, overall the new “ideal” was something in complete contrast to soc-realist Olympian classicism and the noble image of the Soviet artist as the builder of communism. With the assistance of numerous art historians and propagandists, a new and powerful “imprinting”, or what, from the research by Nobel Prize winner Konrad Lorenz, came to be called the “duckling syndrome”, came to be stamped on the consciousness of society, and especially creative youth. Now every student at art school, large and small, was thoroughly obsessed with Van Gogh and his “battle with life”, and also endeavoured to cultivate a rebellious pose. The “ducklings” followed the example presented. Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra was avidly snatched up. Many young artists began to perceive their creative personality as “superman”, locked away in their own ivory tower and rising above the vulgar mob. The majority overcame such exaltation like they would a childhood illness, and successfully continued to develop modernist ideas and controversies, openly and legally surfing the waves of Soviet art and culture. With some surprise it should be added that this type of confrontation (revolutionary artist avant-gardist versus the slow-witted, philistine public) virus has survived right up till these degenerate days of market relations and business, where the customer apparently is always right. The impact of “imprinting” turned out to be very powerful. | |

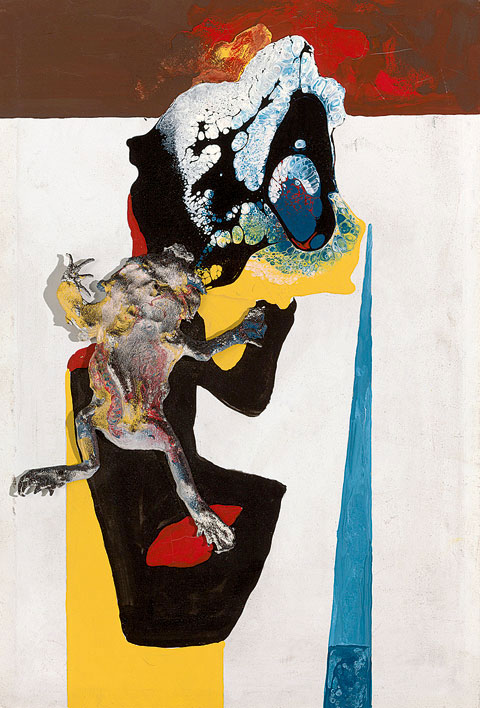

Visvaldis Ziediņš. Road Composition. Alkyd, emulsion, Indian Ink and frog on cardboard. 28x19 cm. 1977 Publicity photos | |

| But obviously it didn’t happen in the same way with everybody. For his part, Visvaldis Ziediņš elevated his disenchantment and alienation from the society around him to principled heights. An entry made in his diary in 1961 provides evidence of a radical determination: “I’m not going to show my pictures to anyone, nor will I take them to exhibitions.” The 19 year old youth also motivated his hard choice on people’s lack of understanding: “How undeveloped they all really are. They find studying issues of art philosophy uninteresting...” Henceforth, Ziediņš “preserved” his true artistic life within the walls of his studio – being free in his closed off fortress or cloister cell. His negative attitude to further education at the Academy of Art can also be linked to this conviction, with him assuming that he wouldn’t be able to learn anything really new within its conservative atmosphere. In current assessments of the artist’s life, a tendency has arisen to idolize this “internal exile” position taken up by Visvaldis Ziediņš as non-conformism, and to interpret it as an individual protest against the regime of the time and its cultural policies. It seems that this is, however, a mistaken evaluation. Ziediņš has never been a fighter against the oppression of the regime, he has never openly confronted it or truly challenged it, as was done by similar contemporaries in Moscow, for example, where a truly bitter underground and a radical non-conformism, persecuted by the regime, existed. At the time, but especially from the end of the 1960s, we find the seemingly out-of-favour expressions of “formalism” quite widely present in the works of many of his Latvian contemporaries. Often its spread had quite an official character, with legal arenas as well as a broad range of supporters. It’s difficult bring oneself to describe those, for example, who were at the time considered honoured Soviet Latvian artists and highly respected in society (in official society too), though quite modernist authors like Kurts Fridrihsons, Boriss Bērziņš, Jānis Pauļuks, Rūdolfs Pinnis, Ilmārs Blumbergs... as being conformist. And it’s hard to believe that the teaching staff working at the Soviet Academy of Art in Latvia, and among them the forward looking ones, would not have been able to teach anything. Therefore it seems that Ziediņš’ non-conformist pose should really be seen in the context of his entire life, not as a proud stand and uncompromising adherence to principle, but rather as a dramatic mistake. This extremism by the artist, the rather naïve assumption of a position and isolationism triggered by the romanticism and maximalism of youth, was costly for Latvia’s culture – the waste of a great talent. Although now it has been very pleasant to relish the newly discovered “exotica” in this huge exhibition. But, in looking over the unique range of works, with sorrow one detects something sad: in it all there are very few works which develop beyond the stage of artistic ideas and conceptual designs. We are convinced about the powerful creative potential, yet its Great Transformation into more ambitious works of art, which would have burst onto the public arena, didn’t follow. It’s like a farmer’s refusal to sow his fields because the weather isn’t good at the moment, and instead, just making do with some test cases grown in flowerpots. So many of Ziediņš’ like-minded contemporaries, after identical doubts and ups and downs, continued to fight in the open “battlefields”. They found a way of acknowledging the principle of contemporary art in Latvian culture and to achieve respect, attention and distinction independently of the opposition or the benevolence of the political climate, and without whining references to Soviet totalitarianism. | |

Visvaldis Ziediņš. Bucket. Cardboard, metal bucket and oil. 37x26x3 cm. 1981 Publicity photo | |

| It is true, though – all of those (especially the responsible cultural administrative powers that be in the city of Liepāja) who should be made aware of the value of Ziediņš’ work, could still significantly correct the lot of his misfortune of fate mentioned. This artist is the pride of Liepāja, and also a national treasure. And many of his works almost “demand” that they should be placed in public spaces as monumental sculptural creations, installations and paintings, which would definitely bring joy not just locally to the city and Latvia, but also wider international fame, and would suitably immortalize the name of an outstanding citizen of Liepāja as well. A similar practice has been implemented in many places around the world. For example, the monumentalization of a Pablo Picasso statuette in fifteen metre reinforced concrete in Kristinehamn, Sweden, which is now the largest modernist sculpture in the world rooted in the classic artist’s concept. It seems that in assessments of our art rebels and “storm petrels”, a higher level of responsibility could be set at times and we shouldn’t allow ourselves illusory conclusions which provoke a certain local-patriotic euphoria: look, he was so radical and original, and should be up there among the many other great pioneers and famous trailblazers of world art. These kinds of thoughts were occasionally suggested by the not-completely-appropriate references to apparently likeminded classic artists such as Jonas Mekas, Wolf Vostell, Nam June Paik, Salvador Dali, Joseph Beuys and others that were woven into the exposition commentary. It seems, however, that our Latvia’s own small “flowering beauty” is still sufficient and valuable in itself, without having to reinforce and justify it even more by comparison with the striking flora of the Western cultural garden. The fighters’ “weight categories” here aren’t equal. The major Western classic artists undertook their historic mission (or had already completed it) with great flourish in an open and free society, but our hero was restricted to remaining in and soaking up the oxygen-rations of ideas which flowed into the available field of information (or even – into a locked cell). The stout Westerners were fortunate to be almost industrial scale disseminators of ideas with large harvests, but our Visvaldis Ziediņš – a tester, investigator, searcher, thinker... The great wonder as revealed by Visvaldis Ziediņš’ exhibition at exhibition hall Arsenāls is a testimony to the delicate expressions of a sensitive soul, as well as the burgeoning and productive activity of an outstandingly enterprising and free spirit at a time and place where nothing really should have been flourishing at all. P. S. Additional food for thought: of the 99 achievements mentioned in Latvia’s Cultural Canon, nearly 39% were created under the conditions of Soviet totalitarianism and another 28% under the Russian Empire. The harder the times, the more energetic the Latvians have been? Or maybe the devil isn’t as black as he’s made out to be? Translator into English: Uldis Brūns | |

| go back | |