|

|

| Exile art out of exile Laura Kenins, Artist, Art Critic An imaginary curation of contemporary “exile artists” | |

| Next spring brings the opening of a major exhibition of Latvian “exile art” organized by the Latvian National Museum of Art at the exhibition hall Arsenals: bringing together works by first and second generation Latvian immigrants from Australia, Canada, the United States and several countries in Europe. The show aims to exhibit principally work of the diaspora which has not been shown in Latvia before – following on the heels of a similar 2010 exhibition of Estonian art in exile at Tallinn’s Kumu art museum – but what is this idea of exile art, and how might a contemporary exhibit of Latvian artists abroad look? The artists announced for the exhibition thus far mainly represent generations of elderly or departed artists, including big Latvian names like Valdemārs Tone, who built his career primarily in Latvia before he was exiled during the Second World War and died in Great Britain in 1958, but few standouts in the contemporary art scenes of their countries of residence (with a couple of exceptions, notably the Australian painter Imants Tillers, who has represented Australia at the Venice Biennale, the Biennal de São Paulo and Documenta). | |

Gints Grinbergs. Stainless Vortex. Stainless steel. Diam. 132 cm. 2011 Publicity photos Courtesy of the artist | |

| What do we mean when we talk about “exile art”? Firstly, there is the problematic nature of the idea of a national art during a time of occupation. Who qualifies as a true representative of his or her country – the artist producing art as dictated by an authoritarian regime, or the artist who has left to create work freely, but now lives in another country? National awards and praise lauded on exiled artists across Eastern Europe (and the general disdain awarded to drab, forgotten socialist realist art) might suggest the latter, though it may not be admitted outright. Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, Lithuanian artists George Maciunas and Jonas Mekas are some of the most celebrated twentieth-century artists of the Baltics, and all left their homelands (though Pärt returned). Secondly, there is the matter of the art itself. For me, and I suspect many other foreign-born Latvians younger than 80, “exile art” conjures up images of weighty oil paintings hanging in the houses of parents, grandparents and elderly family friends, abstract compositions in dark colours, dusty-looking flower arrangements and Old Riga street scenes being favoured subjects. Tied in with this idea of “exile art” is the idea of exile itself, of a particularly Latvian suffering brought over from overseas. In these sombre oil paintings, one imagines the whole weight of this suffering, recruitment into the Soviet or Nazi army, being shipped off to German factories to work, escaping in the night with candlesticks and jewellery stuffed into coat pockets, displaced persons’ camps, being torn forever from homelands or brothers or parents or wives: at least, that’s how it seemed to me as a child. In Latvian communities overseas, the younger generations, of course, generally do not inherit this suffering to quite the extent of their forebears. And, to be an “exile” sometimes means not only exile from the home country, but a self-imposed exile within the host country. As immigrant communities develop where one can go to the bank, the doctor and the bakery while still using their mother tongue, immigrant artists can sell their work to other immigrants, exhibit at community centres and song festivals. But if we interpret “exile” as the broader “diaspora” (as seems to be the usual interpretation with Latvians, even a couple decades after the restoration of independence), plenty of artists of Latvian descent are at work abroad, with practices that shed the weight of “longing for homeland“ and are vibrant and active on the local and international contemporary art scenes. The most renowned artist of the Latvian diaspora, Vija Celmins, was born in Riga in 1938, but emigrated to the United States as a child. Celmins’ work has seldom been displayed in Latvia, but as a rare occasion, her prints were recently displayed in Riga’s Arsenāls as part of an exhibition of mezzotints. Celmins’ work is also currently on view at London’s Tate Britain and she has exhibited at major galleries across Europe and Asia, as well as major American contemporary galleries like the Whitney in New York and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Though she isn’t a participant in the exile artist exhibition, a major exhibition of her work is planned for 2014–2015 as part of the 2014 Riga Capital of Culture celebrations. Celmins studied in Indiana, where her family settled, and completed graduate studies at the University of California in Los Angeles. | |

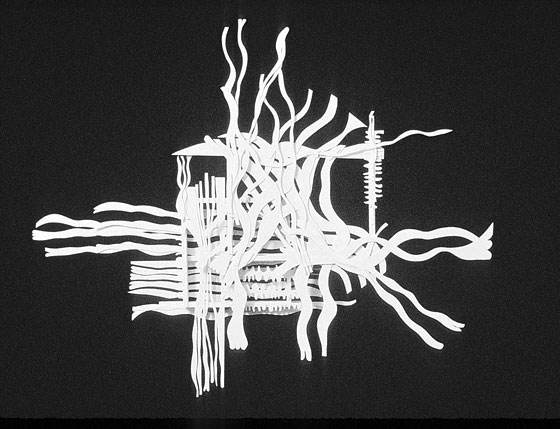

Minka Švarcs. River Laced. Screenprint. 42x30 cm. 2011 Publicity photos Courtesy of the artist | |

| Celmins’ drawings and prints use minute detail. She’s well-known for her recurrent images in prints and drawings – delicate, highly detailed images of spiderwebs, ocean waves, galaxies and the moon’s surface. She works with simple materials like graphite and charcoal, always from photographs. Interviewed for the 2004 monograph on her art,(1) Celmins referred to her work as being about “experience” – the physical process of the drawing or printmaking, a medium that she was also attracted to through the process. Celmins’ early work sometimes focused on still life – a means of rebellion at the end of an era when abstraction dominated – and on disaster-related images: just-fired guns, war planes, mushroom clouds. There’s no obvious connection between Celmins’ art and her Latvian roots, but she has spoken of the influence of being a foreigner, mentioning that she felt like a foreigner again when she moved to California because her work was “too grey” for the state. While she painted bombs and guns in the 1960s and 1970s, she was also participating in the peace movement, having experienced war and exile firsthand. Though Latvia seems content to claim Celmins for its own, her birthplace isn’t Celmins’ central concern – from her interviews, it’s evident she sees her primary role as an artist, and perhaps it’s this grey that was unacceptable to Californians that Latvians are eager to embrace. Of the second generation, Toronto-born Canadian Latvian photographer Vid Ingelevics’ work deals with history, archives and institutions, often with a sense of humour – though sometimes a black humour. His video project Attention: Mr. Inglewick shows a collection of letters Ingelevics discovered after his father’s death. The letters, addressed to his father at his workplace in the 1960s and 1970s, contained around 90 misspellings of Ingelevics, from “Inglewick” to “Ecclestein” to “Iglovicz.” It’s funny, especially to anyone who’s experienced the frustration of trying to have even a simple Latvian name spelled correctly in an English-speaking country, but it’s a dark humour – Ingelevics sees the misspellings, which were primarily made by people who had the correct spelling at hand – as an extension of subtle discrimination against postwar Eastern European immigrants in North America. The name is changed to more English versions like “Inglewood”, while spellings such as “Englihiciz” suggest that any Eastern European-sounding approximation is close enough. Ingelevics comments by email that the piece “stirred up some controversy in Toronto, as some in the Latvian community didn’t feel that it was art”, both due to the non-traditional medium and because it was “probably a bit uncomfortable for others who may even have experienced what I was representing”. | |

Zane Treimanis. Quiet Turmoil. Painted wood. 135x173x15 cm. 1996 Courtesy of the artist | |

| Only a few of Ingelevics’ projects explicitly consider his heritage, though one could argue that an interest in family history and the history of Eastern Europe surfaces subconsciously through many of the places and landmarks he chooses. Ingelevics has photographed museum showcases, archival items and other museological subjects. One recent project photographed the museum guards in art galleries and museums, as part of a larger project called Between art and Art. Other photographs in the series investigate gift shops, stairways, entrances and other “liminal” spaces in museums. In his one solo exhibition in Latvia, Artifact, at the Latvian Museum of Photography in 1994, he froze photographs from the archives of Munich’s Deutsches Museum (which had also served as a displaced persons’ camp after the war) in blocks of ice and documented the ice blocks. An ongoing project, Freedom Rocks, looks at the fate of fragments of the Berlin Wall after 1989 – installed in segments in cities around the world (Riga among them) and sold off as concrete pebbles, working from the premise that the Wall was not destroyed in 1989, but instead sold off in pieces. Ingelevics is currently showing, in two galleries of the Toronto area, work focused on the idea of the archive. Though he says he doesn’t deal exclusively with his roots, his work is “certainly positively influenced by my earlier interest in my family history.” Among the youngest generation of diaspora artists, Australian Latvian Minka Švarcs (Born Antra Švarcs, 1991) is a draftswoman and printmaker from Melbourne. Though she’s only 21, Švarcs has already been travelling around Europe with her work and has exhibited in Riga, also Granada in Spain, and at home in Australia. Švarcs (born Antra) creates obsessively detailed prints and drawings, even taking her pens to the walls at a residency in Granada this year. Švarcs is interested in the relationship of the tangible and the intangible: “Concepts like dream amplifiers, thought fishing, floating cities and talking animals really get me intrigued,” she says. She uses “retro” colour schemes, block colours and elements of Latvian symbols to create other worlds. Currently studying for her Bachelor’s degree in visual communication at Monash University in Melbourne, Švarcs recently returned to Australia after two years living in Europe, six months of which were spent in Riga. Although she grew up in Australia, Švarcs describes her childhood home as a “Latvian mini-cosmos” where she learned Latvian before English and “ate frikadeļu zupa and pīrāgi on a regular basis”. In Riga, Švarcs began screenprinting at the Luste studio in the VEF complex and exhibited her prints at ‘Hedgehog in the Fog’ and Coffee Inn. Švarcs has been inspired by her mother Ilze, a jewellery designer, (her company Vasara Jewellery also combines elements of Latvian imagery and symbolism), and together they have also collaborated on a series where Minka’s etchings were encased in rings and pendants. These are not the only artists of the diaspora, of course: our hypothetical curation might also include American Latvians Ansis Purins (1975), an illustrator and cartoonist in Boston whose work has been published in Kuš! magazine, Brooklyn sculptor and installation artist Zane Treimanis, whose wooden assemblages are frequently exhibited in New York galleries, or metalworker and sculptor Gints Grinbergs, who works with large, fanciful, natural and unnatural forms, often in site-specific installations. From Canada, we could take the work of Laura Ciruls (1958–2008), a painter and graphic designer (at one time with Saatchi & Saatchi) who frequently exhibited her multi-layered abstract paintings in Toronto’s downtown arts scene before she passed away from cancer, or Laura Kikauka (whose father Talivaldis Kikauka was also an artist), an installation artist who has been living between Canada and Berlin for the past twenty years. Kikauka exhibits in Canada and Europe, taking her art supplies from second-hand junk shops and working with brightly-coloured materials, from fake fur to plastic fruit to old records. A 2009 exhibition of sculpture and installation at Toronto’s MKG127 gallery called For the Love of Gaud (Damien’s Worst) paid kitschy homage to Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted human skull For the Love of God. And, certainly, we could add others elsewhere across the globe, since, as it is often said, Latvians are everywhere. Though some artists in the Latvian diaspora seem content with dour oil paintings and exhibiting at Song Festival art shows, there’s little burden of “exile” weighing down these younger generations, displaying a vibrancy and diversity on par with the art scene in Riga today. Although many of these artists have some projects related to their heritage, for others it remains in the background – a subconscious influence or concern, but nonetheless present. Vid Ingelevics comments that many Baltic immigrant artists of his generation and younger have not wanted “to be defined only by their ethnicity,” and he and others successfully break away from that mould, moving away from a sense of exile, either political or – especially since the 1990s – self-imposed. (1) Relyea, Lane, Robert Gober and Briony Fer, Vija Celmins (London: Phaidon, 2004). | |

| go back | |