|

|

| To put things into order Alise Tīfentāle, Art Historian This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s 11.02.–03.06.2012. Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago 30.06.–30.09.2012. Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston 26.10.2012.–27.01.2013. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis | |

| Organizing things is a universal activity, because it is impossible to draw a strict boundary between the material and non-material world. Any conscious reflection on things means putting them into order. Thoughts become deeds and vice versa. Absolutely everything could be put into order – if only we knew how! Unfortunately it is impossible to determine if the order that we have introduced is adequate, objective or correct – our understanding of these notions is inconstant, subject to constant arranging and rearranging. From the modern perspective there is quite a substantial difference between ‘The Etymologies’ by Isidore of Seville, ‘The Encyclopedia’ of Diderot and Wikipedia, but at the time of their creation each one of them was considered to be an adequate way to organize things. The exhibition This Will Have Been is an attempt to organize things mostly in American art (also a little German art and other) between the years 1979 and 1992. The background events often take place in East Village, New York, but not only there. The thematic focal point brought forth by curator Helen Molesworth is the AIDS crisis and the reaction of American political leaders, society and artists, as well as the development of feminist theory. “In 1981 the HIV virus is identified. This is the beginning of what will become a major health and political crisis of the decade”, she has said.(1) The title is borrowed from philosopher Roland Barthes and “his way of talking about the sense of time that is conveyed in a photograph. It’s very melancholic,” according to Molesworth.(2) Molesworth begins her theoretical motivation for the exhibition with the statement that “until recently the art of the 1980s has often been regarded as a kind of embarrassment – excessive, brash, contentious, too theoretical, insufficiently theoretical, overblown, anti-aesthetic, demonstrably political – as though the decade were just too much.”(3) Enough time has now passed for museums to canonize and mystify the phenomena of the 1980s, and to wrap them up into a package as historic drama, similarly as with the previous decades of the 20th century. Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson are among the classic pop icons who have passed away, so at least something could already be classified.(4) In this aspect one can draw parallels with the campaign-like exhibitions that have been held in Europe over the last few years, dedicated to the year 1989 and the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the USSR and the end of the Cold War. It cannot be denied that the historical drama of Europe and Latvia, too, is very different: if we were to put it in simple and general terms, the topics of homosexuality, women’s rights and racism just about did not exist in the public discussion space of Latvia in the 1980s. | |

Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Untitled. (Perfect Lovers). 1987-1990 Photo: Wadsworth Athenum Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY | |

| At the same time, if one wishes to do so, it is possible to find things in common. The curator emphasizes that “for many 1980s artists, making art was itself propelled by the desire to participate, in a transformative way, in the culture at large”(5) and that culture itself can influence the whole of society. In this sense the politicization of art, albeit in a more gentle form, can also be discerned in the 1980s works of several Latvian artists. The theoretical foundation of the exhibition – an introductory article by the curator and essays by other art historians in the exhibition catalogue – represents an art history indoctrinated by feminism, Marxism and Freudianism. The most frequently mentioned names in the essays are from the influential October group: Rosalind Kraus, Hal Foster, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin Buchloh, Douglas Crimp and others; Marx, Barthes, Lyotard and Lacan are quoted as well. Besides AIDS and feminism, which according to Molesworth significantly changed American art and society in the 1980s, just as important are the issues of racial equality, gay and lesbian rights and gender issues as such, postcolonial territories, the crisis of democracy, destabilization of narrative, etc. Even though the attempts to seek out references to class, gender or racial issues in every piece of art can at times become if not tedious, then at least predictable, we don’t have an alternative, do we? The Traumatized Painter Thematically the exhibition is organized into four sections, all pervaded by the subject of death, illness or at least some type of trauma. One of the sections is called “The End is Near” and it focuses on discussions in the 1980s about the death of painting. According to the curator, everyone felt the end of something during the decade, be it the end of painting, counter-culture, history or modernism. This eschatological mood is not devoid of a few elements of irony, however. For example, Frazer Ward characterizes the painting of the 1980s as a zombie or a vampire, pointing to the self-criticism of painting as a medium by cult painters such as Richter and Kippenberger “Bitten, poisoned, tainted – our painter was traumatized, but without having been killed off was also, in however qualified a fashion, liberated.”(6) Painting in this decade was still the cornerstone of the Western art market, and any smallest doubt about its position of authority could in an instant shake up the whole industry, including museums, collectors, galleries and auction houses. This kind of upheaval was a blessing, because the crisis of painting opened the doors of museum collections to photography, installations, performance art and everything else that one can expect on entering any respectable museum of contemporary art today – because painters had begun to work on “everything else” but painting. The best example is Martin Kippenberger’s two works: the painting 6. Preis (1987) which serves as a comment on painting as a competition, and the installation Put Your Freedom in the Corner, Save It for a Rainy Day (1990), which expresses the artist’s provocative protest against the destruction of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany. Kippenberger makes references to Joseph Beuys, who had once proposed to raise the height of the Berlin Wall by five centimetres for aesthetic reasons – the beauty of proportion.(7) The photograph Living Room Corner, Arranged by Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Sr. (1984–1985) by Louise Lawler (born 1947) shows an abstract painting by Robert Delaunay which is partially hidden from view by a television set in the living room of the famous New York collectors. Within the context of this exhibition, this photograph can be considered to be a somewhat critical remark about the function of painting (and art in general) as a commodity in capitalism, as well as the modern-day hierarchy of the media, where television is the highest regarded of all the arts. Democracy and AIDS The section “Democracy” is devoted to the criticism of democratic processes, examining consumer society, popular culture and subcultures as elements (or rather – the consequences) of democracy. The curator points out that the artists represented in the exhibition, the majority of them born in the 1950s, “belong to the first generation to have grown up with a television in the home. They came of age in a culture shot through with visual regimes designed to promote desire across a variety of spectra: desire for objects, for lifestyles, for fame, for conformity, for anti-conformity.”(8) Molesworth links the role of television with the concept of “desire” in its psychoanalytical reading, which in its essence is an insatiable desire for “that which I don’t have”; moreover, the curator emphasizes the connection of this desire with consumer society. One can only add the comment that even in societies in which there isn’t really anything much to consume, television as a medium of mass communication is able to produce and simultaneously satisfy uncertain, nevertheless real desires without even a single commercial (because why else would we have been watching programmes such as Vremya, Panorāma, the Sanremo Music Festival and Mikrofons 86 during the Soviet occupation)? | |

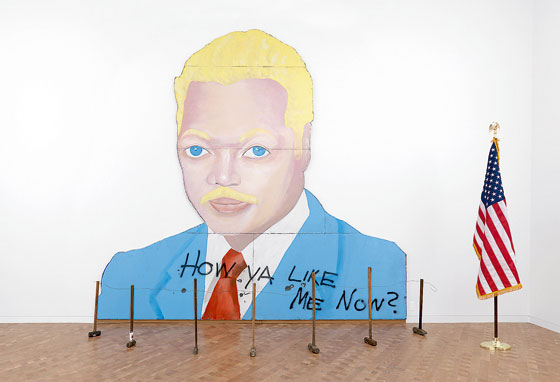

David Hammons. How Ya Like Me Now?. 1988 Photo: Tim Nighswander / Imaging4Art Courtesy of MCA Chicago | |

| In addition to the comprehensive economics of desire, Molesworth also turns to Reagan’s conservative politics and the use of the mass media for political aims. Reagan and Thatcher are referred to as symbols of the decade quite often, and not only in the essays. One of the first works that the viewer encounters at the exhibition is the work Oil painting: Homage to Marcel Broodthaers (1982) by Hans Haacke (born 1936). A red carpet leads from the museum-like and presentable portrait of Reagan to an uncannily enlarged photograph of a mass protest in Bonn during Reagan’s visit there. One person against the crowd, one power against another, painting against photograph, fiction against documentary, etc. – the themes are handed to the viewer as if on a silver tray. But we are only a couple of generations away from the time when a work such as this, even if it found its way into a museum exhibition, was there for quite different reasons than now, and the description attached – who is Reagan, what is a mass protest, why Bonn, etc. – for the majority of museum visitors will seem just as distant, foreign and irrelevant as, for example, a description of the ‘Oath of the Horatii’ by David is today. In the context of this exhibition, Reagan is the personification of all evil. As the curator points out: “The AIDS crisis created a condition in which the “public” was increasingly articulated as white and heterosexual, so much so that when asked why President Reagan had not yet uttered the word “AIDS” out loud (in 1985), his spokesperson could say: “It hasn’t spread to the general population yet.”(9) In reality, AIDS had quickly become one of the most topical issues in the public space. Artists also became involved in the work of public organizations and movements, and at the very least tried to reduce the prejudice, created by misleading information or a complete lack of it in American society. The educational poster Kissing Doesn’t Kill (1989), created by a group of artist-activists Gran Fury, tried to draw public attention to erroneous preconceived ideas about the possible ways of becoming infected by the HIV virus. The posters were on display in San Francisco, Washington D.C., Chicago and New York, and very soon after that, in 1990, Gran Fury made their grand debut at the Venice Biennale, with an attack on the Pope’s pronouncements about the prohibition of the use of condoms in a Catholic lifestyle. The Order of Things in Gender Issues A few days ago, whilst filling out an official form, I was offered this choice of gender: 1) male, 2) female, 3) other. The fact that gender is a socially constructed identity and not a naturally or supernaturally decreed “order of things” is a self-evident notion thanks to the feminist movement of the 1970s and 80s. The curator has named one of the sections of the exhibition “Gender Trouble” in reference to Judith Butler’s book Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990). As one of the more important reference points in forming an understanding and representation of gender roles Molesworth mentions the work The Dinner Party (1974–1979) by Judy Chicago. Besides, it’s not only female artists who have the right to participate in the process. Often it is the artworks created by male artists that most eloquently put across the message of “how the structure of representation worked silently to shore up the power arrangements of patriarchy.”(10) Among these works is Picture for Women (1979) by Jeff Wall (born 1946). There exists a substantial amount of writing about this work,(11) and it is an especially attractive object of research for art historians whose work is influenced by feminism and the theory of psychoanalysis. Just like Manet’s painting to which Wall refers in his work, or Las Meninas by Velazquez, theoreticians can perpetually and patiently go on and on explaining who is looking where, drawing imaginary lines until they cross over each other in an endless web, abundantly quoting from Foucault and each other, as if that were to put everything in order. Not far from a painting by Lucian Freud, we come across an odd work belonging to the genre of the grotesque – Self Portrait with Shitty Underpants and Blue Mauritius (1984) by Albert Oehlen (born 1954). To make everything unmistakably clear, the accompanying commentary states that the Blue Mauritius is the most valuable historical postage stamp in the world. One can only agree with the curator that “here the neo-expressionism of the work connotes more failure and anxiety than it does triumph or artistic authenticity”.(12) The role of the man in a traditional (patriarchal) family has been tragicomically played out in Paul McCarthy’s (born 1945) video Family Tyranny (1987). On the other hand, art historians are convinced that Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man (1984) by Eric Fischl (born 1948) reveals castration anxiety as defined by Freud and “this focus on the ultimate weakness and fragility of the construction of masculine identity differentiates him from the heroic gestural painting of most of the neoexpressionists, who attempted to resurrect the image of the heroic male artist performing his virile subjectivity in paint”(13). The slideshow The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1979–2001) by Nan Goldin (born 1953) is one of the most significant points of reference in American art of the second half of the 20th century, as is Cindy Sherman’s (born 1954) untitled series of photographs. In both cases the female artists were commercially very successful, both used photography as an art medium, and the influence of their works transcended the boundaries of art and left an impression on popular culture, the fashion industry and other areas. Goldin’s slideshow, accompanied by music, brought a formerly private phenomenon into the public space: slides of friends and family, thus assigning the function of art to the everyday, the domestic and the private. One can assume that this transition was encouraged by the exotic veneer of the quotidian life photographed by Goldin: had her friends and acquaintances not had such a rich and expressive collection of various addictions, expressions of sexuality and versions of alternative life styles, her photographs would have not made it into museums. | |

View from the exhibition This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s Photo: Nathan Keay Courtesy of MCA Chicago | |

| As befits an art canon, the official interpretation of Goldin’s achievement has been polished to perfection and is repeated without any special variations – mirror of the community, source of memories and nostalgia, memorial to daily life, research into the experimental and passing nature of identity, not forgetting to mention that AIDS has claimed the lives of its many heroes, and that the photographs are irrefutably feminist because they convey a message about women’s rights.(14) Most likely it is impossible to say anything new about Goldin’s Ballad. At the same time this work makes us think about the role of good fortune and lucky coincidences, both as regards the career of an artist as well as in contributing to the overall history of art (as a series of outstanding and significant works). With the exception of occasionally unusual outward appearance – the clothes and the makeup – the counter-culture heroes of the late 1970s and early 80s of New York in Goldin’s sentimental photographs mostly seek to achieve the most mundane and most bourgeois of aims (marriage, children, a peaceful home, entertainment), even though the protagonists often enough lose their way and their path towards this goal is not so straight or fast. Looking at Sherman’s works, meanwhile, the first thing that comes to mind is their mindboggling price tag. For example, a copy of Untitled #153 (1985) was recently auctioned for about 3 million US dollars. This work has been included in the exhibition because it portrays a woman (gender issue) and also because the woman is most likely dead (hence a reminder of AIDS). Just as it is in the case of Goldin, there is a certain accepted way to write and talk about Sherman’s work, with quotes from Laura Mulvey, Rosalind Krauss and Julia Kristeva.(15) However, I don’t see a reason to ignore the status of these works as a commercial product and thus placing them into a certain category of contemporary culture and consumer society. The Analysis of Desire The section “Desire and Longing”, lavishly quoting Roland Barthes, claims that in the 80s anything and everything was seen as desire.(16) In a fairly witty manner, appropriation is also interpreted as desire: the use of existing objects, images and artworks in the works of Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince and others is seen as the materialization of desire. Furthermore, according to the curator, this must be viewed in relation to the visibility of homosexuality brought about by the AIDS crisis.(17) In the total context of the exhibition, appropriation in the art of the 80s is re-evaluation, critique and irony, and to an extent also an attack on the imagined genius and originality of the artist, yet another incidence of questioning patriarchal authority. The work Buffalo (1988–1989) by David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992) can be considered to be one of the central works of this section. The photograph is a selective crop by Wojnarowicz of the diorama displayed at the National History Museum, Washington D.C.: buffalos as they are being chased over a cliff by hunters who have been left outside the frame. The artist has intended this powerful image as an illustration of the Reagan administration policy with regard to AIDS victims. Another work which is just as significant is Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1987–1990) by Félix González-Torres (1957–1996). This work consists of two ordinary battery-operated clocks placed side by side. The clocks are set to the same time, but gradually, as the clock mechanisms wear out, they fall out of synch. The work is extraordinary in its simplicity, and typical of González-Torres’ style. The curator emphasizes that this work is a “condensation of the fears and apprehensions about the success of either love or life amid the devastating waves of death that permeated communities of gay men and people of color”.(18) In my opinion, however, this and other works by González-Torres do not necessarily highlight that the world of “homosexual men” and “coloured people” is different, on the contrary – they show what is common to all. “Desire and Longing” to a large extent continues to deal with issues regarding the process of normalization of homosexuality, bisexuality and other sexual practices in the 80s, which is one of the key themes of the exhibition. In Deborah Bright’s (born 1950) series Dream Girls (1989–1990), a woman in male clothing is montaged in amongst the male characters in black and white scenes from classic cinema. This creates confusion about the supposedly obvious division of functions between “man” and “woman”. Nearby there are also photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–1989). One is led to think that Mapplethorpe might have been just one of thousands of boring and obscure aesthetes, if instead of photographing extremely beautiful flower compositions he had not turned to photos of sexualized black male nudes. As with Goldin, all other aspects of the artist’s creative work are overshadowed by one big “challenge”, which in this case is being demonstrated as an object of fetish, an object of the viewer’s desire. Reviewing the List A few individual voices among the American public point out works that are missing – even though the title of the exhibition clearly defines a thematic approach, there are some who think that the show should have offered a more complete reflection of the decade, and that it should comprise stars only. If we have Herring, Mapplethorpe and Schnabel, then where is Warhol?(19) Why aren’t Anselm Kiefer, Francesco Clemente, Andres Serrano, Maya Lin, Sigmar Polke and others represented?(20) The public is worried – where is Basquiat? (His work will be seen at the Boston and Minneapolis versions of the exhibition.) It is inspiring that Honoré de Balzac considered the writing of novels to be a sort of obligatory bread and butter job, but his real passion was the organization and cataloguing of his possessions into neat lists.(21) In this exhibition everything is so well organized and carefully explained, that one could remain under the impression that that’s how things really are. However, a few things remain open to interpretation. For example, what should be the viewer’s attitude towards the fact that the exhibition This Will Have Been often brings to the fore specific aspects of the artist’s personality and private life – race, gender, sexual orientation, in some cases even the cause of death (if it was AIDS)? The artworks are viewed in tandem with the most intimate aspects of the artists’ biographies, which perhaps is justified by the main concept of the exhibition. /Translator into English: Vita Limanoviča/ 1 Helen Molesworth quoted in: Patrick G. Putze,’Steeped in Crisis’, F Newsmagazine, March 3rd, 2012. fnewsmagazine.com (accessed 18.03. 2012.). 2 Bonnie Rosenberg, ‘This will have been: Art, love and politics in the 1980s’, The Art Newspaper. www.theartnewspaper.com (accessed 08.04. 2012). 3 Molesworth, Helen Anne. Art, love, and politics in the 1980s. In: This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s. Ed. by Helen Anne Molesworth. Chicago; New Haven: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 2012, p. 15. 4 Sam Worley, “Will the 80s ever end?”, Chicago Reader, 16 February, 2012. www.chicagoreader.com (accessed 18.03.2012.). 5 Molesworth, Helen Anne. Art, love, and politics in the 1980s, p. 17. 6 Ward, Frazer. Undead painting: life after life in the 1980s. In: This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, p. 53. 7 Stark, Trevor. Martin Kippenberger. In: This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, p. 88. 8 Molesworth, Helen Anne. Art, love, and politics in the 1980s, p. 17. 9 Ibid, p. 30. 10 Ibid, p. 33. 11 One of the most recent works is: Campany, David. Wall, Jeff. Jeff Wall: Picture for Women. London; Cambridge: Afterall Books, 2011. 12 Molesworth, Helen Anne. Art, love, and politics in the 1980s, p. 35. 13 Lotery, Kevin. Eric Fischl. In: This Will Have Been: Art, Love &Politics in the 1980s, p. 271. 14 Grace, Claire. Nan Goldin. In: This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, pp. 275–280. 15 Quick, Jennifer. Cindy Sherman. In: This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, pp. 296–298. 16 Lebovici, Elisabeth. How soon is now: Longing and desire in the art of the late twentieth century. In: This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, p. 319. 17 Molesworth, Helen Anne. Art, love, and politics in the 1980s, p. 19. 18 Ibid, p. 43. 19 Caryn Rousseau, ‘1980s come alive in Chicago museum show’, USA Today, 3 March, 2012. www.usatoday.com (accessed 18.03.2012.). 20 Patrick G. Putze,’Steeped in Crisis’, F Newsmagazine, 3 March, 2012. fnewsmagazine.com (accessed 18.03. 2012.). 21 Maleuvre, Didier. Museum Memories: History, Technology, Art. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1999, pp. 124–128. | |

| go back | |