|

|

| Urinals, Lithuanians and FLUXUS – épater la bourgeoisie Jānis Borgs, Art Critic | |

| In the beginning there was Dada Art is dead. Long live Dada! – cried the German-speaking Austro-Hungarian-born avant-garde Carlsbad writer and Jew, Walter Serner in despair, (1889–1942; he was also known as Seligmann) in his Dadaist manifesto published in 1920. In the heap of so many other Dada manifestos, an international horde of no less exalted like-minded persons concurred with him. All of them also insisted that “art is dead!”. It was the First World War that drove these and other European intellectuals – poets and artists – into a forbidding cultural storm cloud. The irrational slaughter of millions in the “civilized West” gave them justifiable reason to cast doubt upon and ridicule “Christian values” as well as all bourgeois culture and morality, which now revealed a complete inability to keep society within the bounds of their pathetically declared ideals. The face nurtured by Christian and civilized European culture had clearly taken on the features of cannibalistic savagery and vampirism. What sort of art could be spoken about while trampling over piles of corpses and drowning in a sea of blood? The Dada lads, like German deserter Hugo Ball (1886–1927), Romanian Jew Marcel Janco (1895–1984), German poet, drummer and “art bolshevik” Richard Hülsenbeck (1892–1974), German-French poet and artist Hans Arp (1886–1966) and others, settled themselves in the Swiss oasis of peace Zurich in 1916. The concept of épater la bourgeoisie (‘shock the middle classes’) as sown by poets Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud and various French Decadents in the mid 19 century, at the very dawn of modernism, and so vividly embodied by the grand impressionist “mutiny” on the ship of academia, could now thrive in the fertile soil already scarified by the raging Futurists. To make fun of and shock the bourgeoisie has been the universal task of every type of avant-gardism throughout history. Now, during the Great War, it gained momentum again as never before. It solidified into anarchistic and provocatively scandalous anti-art activity – in Dadaism, where nihilistic absurdity and “nothing” were raised to the status of being basic principles. Initially Dada, perhaps, was only a sort of provocation, an artistic commotion, a form of protest... | |

Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik organized by George Maciunas in Wiesbaden, Germany. 1962 Photo: Hartmut Rekart | |

| Now it was another French poet, also a Jew of Romanian origin and one of the previously-named company of Dada emigrant comrades, the 19 year old Tristan Tzara alias Samuel Rosenstock (1896–1963), who on 5 February 1916 introduced activities at the newly opened Cabaret Voltaire with a scandalous performance. The young man, wearing a monocle, sang provocatively sentimental songs and handed out balls of cotton wool and paper to the confused audience, before abandoning the stage to actors on long wooden stilts... For this, what seemed to them a villainy, the conservative burghers would occasionally beat up the Dadaists, and every so often a wave of intolerance, typical of the rest of the world, would surge up in some tavern. Dada and Ilyich The Cabaret Voltaire was located (and still stands) in a building at Spiegelgasse 1. But about a hundred metres further on the same street, at house at no. 14 belonging to the shoemaker Kammerer, once lived, together with his dear Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya, the famous Vladimir Ilyich Lenin himself. Here he quietly fomented revolution, submersing himself during the day in the depths of the library or reading lectures about socialism to workers at the People’s Hall. But in the evenings he too would frequent the neighbouring Cabaret Voltaire, where he could get a cheap bite to eat, drink some beer and listen to Hugo Ball mumbling his Dada poem: ...gadzhi beri bimba e glassa tuffm i zimbra... Vova liked all of this hohma, and he didn’t hurry home to the embraces of his dear Nadezhda. There is written evidence that Lenin eagerly joined in with the Dadaist escapades, playing his balalaika and even trying his hand at composing verse. But with Tristan Tzara, the Dada leader, the future leader of the revolution and “Tsar” of Red Russia loved to play chess, with a friendship almost forming. Neither Ilyich himself nor the Dadaists had any notion that the greatest mega-Dadaist in the history of the world had arrived in the person of “Herr Ulyanov”, whose revolution would in about a year or two turn out to be the most concentrated essence of Dada absurdity and the most extreme épater la bourgeoisie: expropriations, de-kulakization, hostages, shootings without trial, gulags, the KGB, class war... The bourgeoisie would get a fright, indeed! Whereas Tristan Tzara, the future French Communist Party member, knew that Vladimir was a Russian Socialist “рэволуционэр” [revolutionary], but had no idea that the latter would soon be the capo di tutti capi of all the world’s Communists... as Tristan at the time was convinced that he himself was the leading surfer on the biggest wave of the global cultural revolution. Thus the two “Tsars” merely drank their tea together, without even recognizing each other’s greatness... In between their absurd poetry readings and mayhem, these rebels would compose and announce to the world innumerable grotesque manifestos. The first of these came out on 14 July 1916, which is why this date is considered to be the birthday of Dadaism. The new anti-art promoted the denial of traditional culture, morality, beauty and aesthetics, as well as meaning. “It’s not Dada that’s nonsense, but the essence of our age that is nonsense,” – so stated the young activists. Ilyich’s chess partner Tzara commented on what was happening: “The question, ‘What is Dada?’ – is unDadaist. Dada cannot be understood, it has to be experienced.” Just like Fyodor Tyutchev’s famous lines: “Who would grasp Russia with the mind… By faith alone appreciated”. Hugo Ball thoughtfully concurred with Tzara: “What we call Dada is a piece of tomfoolery from the void, in which all the lofty questions have become involved.” And the gloomy poetism of the avant-garde writer, theoretician and artist with a particular ethnic mix (Polish, Georgian, French, Russian), Ilya Zdanevich (Илья Зданевич, 1894–1975) too: “Art died long ago. My untalented creative work – is like a beard growing on the face of a corpse. Dadaists are banqueting worms – see, that’s our main difference.” Whereas German Dada artist Hans Richter (1888–1976) attempted to explain the motivation behind the new direction in a more constructive way: “Dada is not an artistic school, but rather an emergency alarm warning against the collapse of values, against routine and speculation, a desperate challenge to build creative foundations in the interests of all art and forms which would allow the building of a new and universal consciousness of art.” But his contemporary Richard Hülsenbeck, in true Buddhist-Dadaist fashion declared: “Dada means nothing. We want to change the world with nothing.” In this way an elitist, but overall mainly Left-oriented direction came about, which gradually created a favourable breeding ground for, and generated striking expressions of, Dada activities in other major cultural centres around the world – in Berlin, Cologne, New York, Paris, Tokyo... Initially, society didn’t really take the Dadaists seriously. “Look, some kind of psychopaths are fooling about...” Nobody really had an inkling that Dada would essentially, and in a revolutionary way, change the understanding of art and radically alter the course of its development, blending reality with art into one whole. The revolution of the urinal In this context perhaps the most important of all the Dadaists Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), the French and American artist and theoretician who shattered the old language of art to its very foundations, should be especially highlighted. In 1917, in New York he “created” the most chresthomatic and, possibly, also the most cynical Dada work Fountain which was one of the most famous of his ready-mades: a common shop-bought urinal. At first, even the most radically inclined of his like-minded colleagues did not appreciate such a crass juggle of non-art. The urinal was thrown out and forgotten, and the only thing that remained was a documentary photograph by the famous American photographer Alfred Stieglitz. | |

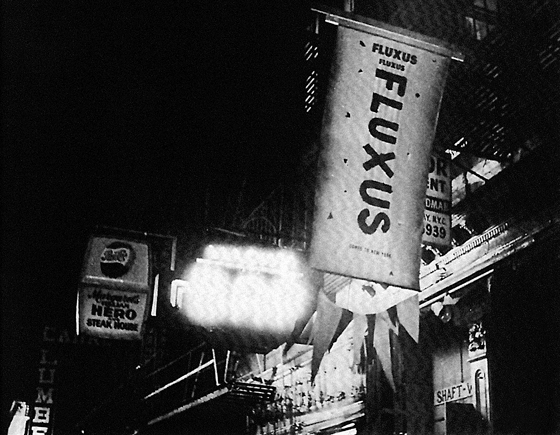

The banner of Fluxushop in New York. 1964 Photo: Peter Moore | |

| The decline of Dadaism had already set in by around 1922. Its creative and conceptual energy transformed mainly into Surrealism, although some parts went to other “isms” as well. It was only after the Second World War that Dadaist thinking began to emerge again from the 25–30 year mist of silence. Marcel Duchamp repeated a copy of the first urinal in 1950, and then, in the period up to 1964, about another ten authorized replicas followed. Now the value of this “junk” was rising to the million dollar level and many world art historians, ignoring the indignation of “polite society” and the “general viewer”, recognized Duchamp’s urinal as the most influential artwork of the 20 century. It should be emphasized: specifically the most influential – the one from which flowed the most radical consequences – but not the most beautiful or the one with the most substantial contents. The mercilessly scandalised bourgeoisie once again showed their capacity to digest and absorb extreme cultural ideas. Non-art – Dada – finally came to rest in academic art research folios, on shelves and in the despised museums, like yet another exotic butterfly pinned down in a collector’s case. The once so shocking and liberal lion of non-culture now meekly sat in the cage of the bourgeois salon. Unfortunately, the destiny of all the avant-garde... Again we can calmly quote the Dadaist slogan “Art is dead!” with the ironic aside “Long live art!”. Just as for those deceased, but eternally living kings... The finest hour of the Lithuanians Now once again, though completely unexpectedly, our confreres – Lithuanian brothers appeared on the world art avant-garde arena. The Second World War was rapidly drawing to a close, and in Lithuania too, just like here, many people decided not to wait for the next-in-turn “liberators” and in 1944 escaped to the West together with the fleeing Germans. Thirteen year old George Maciunas (1931–1978) also ended up in this stream of people, together with his parents – his father Alexander, a highly educated architect and electrical engineer, and his mother Leokadija, a Russian from Tiflis, ballerina and former private secretary to the pre-Bolshevik Prime Minister of the Russian Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky himself. Somewhere else in this same stream of people moving away from the Reds there were the Mekas brothers – Adolfas Mekas (1925–2011) and 22 year old Jonas Mekas (born 1922), who already had some of their own scores to settle, both with the Soviets and the Germans. The future paths of all of these refugees, with a few individual nuances, followed a similar scenario: a Germany in ruins, DP camps or life in rented premises, emigration to the USA at the end of the 1940s... Two weeks after arriving in the USA, Jonas Mekas had already borrowed some money and purchased a Bolex 16 mm camera, thus beginning his independent life in the world of making and promoting independent cinema. Within some ten years the humble Lithuanian immigrant had become the “godfather” of avant-garde cinema for the whole of America. George Maciunas’ path to the heights and fame of art avant-garde, in turn, was up the ladder of the outstanding education generously provided by America: graphic design at the Cooper Union College for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York, architecture and music theory studies at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, art history at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, music composition at the New School for Social Research. It was right there, in the mid 1950s, that he met the up and coming stars of avant-garde art: the organizer of happenings Allan Kaprow (1927–2006), the creator of event scores George Brecht (real surname MacDiarmid (1926–2008, pseudonym in honour of Bertolt Brecht), the English composer and poet Dick Higgins (1938–1998), as well as the future wife of Beatle John Lennon, the Japanese banker’s daughter Yoko Ono (born 1933; yoko meaning ‘child of the ocean’ in Japanese), who stood out with mulifarious activities in all sorts of avant-garde arts, in the feminist movement and in her manipulations with men. | |

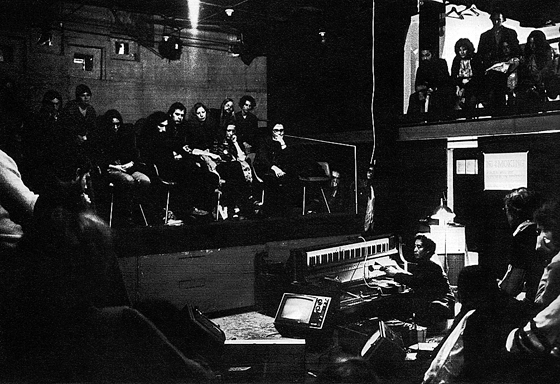

George Maciunas. In Memoriam to Adriano Olivetti. Performance in Fluxshop. 1964 Photo: Peter Moore | |

| And it seems that it was precisely at this school that the next “diamond” in the development of the avant-garde was crystallized, by the grace of fortune procured by George Maciunas and later given the name Fluxus. In many ways, the presence of the guru of 20 century avant-gardism and experimental music master John Cage (1912–1992) or, as some envious Latvians have deemed him, Jānis Krātiņš (using the literal meaning of ‘cage’ in Latvian) at the school was critical. He taught composition there. How important it is to be always in the right place at the right time! Here we can note a deviation that is uncharacteristic of modernism, as in previous decades and already since the time of the impressionists the spiritual leaders of various “isms” had always been poets and writers, for example Emil Zola, Guillaume Apollinaire, Andre Breton, Paul Eluard, Filippo Marinetti, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Tristan Tzara... and many other “bees” collecting pollen for ideas in the hives of art. The influence of composers and musicians had always been insignificant there. But not this time, as with his multimedia grasp and scope, John Cage was already one of the most authoritative leaders of the post-war world avant-garde. His 1952 non-composition for symphony orchestra ‘4’33’’ with its four and a half minutes of absolute silence in a way announced the return of the spirit of Dadaism with a resounding roar and set the scene for the coming Fluxus phenomenon. It was one of many modernist efforts to achieve the next-in-line minimalist zero position which, it seems, had been so successfully introduced in 1915 by the Black Square painted by Kazimir Malevich. George Maciunas and the birth of Fluxus In 1961 in New York, at 925 Madison Avenue, together with his Lithuanian friend Almus Salcius (1925–2000) George Maciunas founded the AG Gallery, where they hoped to hold abstractionist exhibitions. To cover all of this financially, they planned to sell exotic delicacies and rare musical instruments. The gallery drew the attention of enfant terrible avant-garde composers La Monte Young (born 1935) and Richard Maxfield (1927–1969). Behind them stood such 20th century music greats as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, Aaron Copeland and others. At that time, the role of the avant-garde art salon in New York was also assumed by the attic dwelling (or loft as it’s called nowadays) of George Maciunas’ contemporary Yoko Ono and her husband of the time, composer Ichiyanagi Toshi (born 1933) at 112 Chamber Street in Manhattan. Both here and at the AG Gallery nearly all of the future famous New York Fluxists gathered together, performed, staged happenings, exhibited and held concerts. Here, at the beginning of the 1960s, ever new “satellites” appeared in George Maciunas’ orbit, future classic artists such as Christo and Andy Warhol, who most likely got his Factory idea directly from the Fluxus ‘flow of life’ concept. And somewhere here Jonas Mekas’ path finally crossed that of his “fluxing” national compatriot George Maciunas. If we mention the crossing of Lithuanian paths here, then looking a short time ahead, we may remember that Vytautas Landsbergis (born 1932), also a musician, was also included among the Fluxists. He who provided the greatest “politfluxus” contribution to the destruction of Ilyich’s own “mega-Dadaist” creation and legacy. George wasn’t so successful at business, however. After a few months the gallery went bankrupt, and creditors began to pursue the young entrepreneurs who then had to make themselves scarce in a hurry. But, as we’ll see, every cloud has its silver lining. In 1961, together with his friend Almus, George Maciunas headed back to Europe where he’d been born and settled in West Germany, where he began to earn his living working as a creator of art at the American Air Force Base in Wiesbaden. Perhaps the work with staff at the military base wasn’t under such steely discipline as it would have been on the Soviet side, where not even a mouse could get past the watchful eyes of the KGB and the intelligence services. The former “refugee fleeing the Communists” – if this term could be applied to a teenager – had, in the mileu of American Leftist intelligentsia, become almost a supporter of Marxism and Communism. Artistically there was a certain infatuation with 1920s Russian Futurism, Suprematism, Soviet Constructivism and the culture of the proletariat. George loved to study Russian avant-garde magazines of that time, discerning a kindred spirit in Mayakovsky and his muse – his lover Lilya Brik. At one moment he became obsessed with the impetuous idea of heading to the USSR to meet with Nikita Khrushchev and of convincing him to open a Fluxus centre in Moscow. But he still hadn’t heard about “our dear” Nikita Sergeyevich’s colourful evaluation of the modernists. Meanwhile the Kremlin comrades bumped their boss Nikita off to the side quicker than the SovietFluxus concept had matured sufficiently for a campaign. At any rate, George couldn’t see a potential “fluxing” comrade-in-arms in the much gloomier Leonid Ilyich. Still, in Wiesbaden alongside his quiet daily job with the American army George Maciunas was finally able to brew up a significant international avant-garde arts “concoction”. In September 1962, the first Fluxus or Festival of the Newest Music took place, where various happenings, actions and, the main thing, 14 scandalous concerts burst forth from his newly-discovered European avant-garde accomplices and like-minded persons. Among the works was action composer and multimedia artist Philip Corner’s (1933) vandal-like Piano Activities, as interpreted by Maciunas and performed by an international team of “supermen” (Emmett Williams, Wolf Vostell, Nam June Paik, Dick Higgins, Benjamin Paterrson and George Maciunas). The concert, consistent with the scenario, finished with the complete dismantling and destruction of a piano. Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage also participated in the festival. The scandal was so great that German television continued to repeat the events at the concert many times over. George had now gained international recognition, but his mother, after watching the TV news, refrained from going outside her apartment for many days, as what would the neighbours and acquaintances say about the activities of her dear son – the “Nero of Culture”? It should be appreciated that, despite the declared liberties of the “free world”, the greater proportion of bourgeois society and the middle class was dominated by quite a totalitarian traditionalism and conservative spirit, which many were prepared to defend even with their fists. A new urinal-record had now been reached, only this time it wasn’t overshadowed by the destiny once, long ago, experienced by Marcel Duchamp’s arrogance. This time, after the scandals there was also a great demand. The Fluxus Festival with its series of crazy concerts moved on to Cologne, Düsseldorf, Paris, Amsterdam, The Hague, Nice and Copenhagen... | |

Flux-Sonate II by Nam June Paik in Anthology Film Archive. 1974 Photo: Peter Moore | |

| Initially it had been hoped to name this flaring up of avant-gardism as “neo-Dadaism“. But George Maciunas had mustered up the courage to write to the most prominent Berlin Dada classic and old master Raoul Hausmann (1886–1971), who in his response of 1962 wrote the following wise words: “I think that not even the Americans should use the term “neo-Dadaism”, as ‘neo’ doesn’t mean anything, but ‘ism’ is old fashioned. Why not simply say Fluxus? This seems much better to me, as it’s something new, but Dada belongs to history. I contacted Tzara, Hülsenbeck and Hans Richter in relation to this question and all of them said: neo-Dadaism doesn’t exist... All the best.” The name Fluxus, from the Latin meaning “flow”, was to be the name of the little magazine that was going to be published by Maciunas. A flow of life, like art – maybe that was the initial idea. Fluxus was also published in the period from 1964 to 1975, but overall the term stuck to all “neo-Dadaist-type” multimedia artistic activities, or the direction – if we could call it that – as a whole. Here expressions of musical experimentation dominated, but there was no shortage of paradoxical visuality, happenings and performances, provocations, interludes, gags... This was all tried out in some way in Futurist, Dadaist and Surrealist actions. The triumphant (as regarded from the positions of Leftist youth and avant-garde supporters) events were crowned by George Maciunas’ 1963 Fluxus manifesto, which invited one to “purge the world of bourgeois sickness, ‘intellectual’, professional and commercialized culture (..) PROMOTE A REVOLUTIONARY FLOOD AND TIDE IN ART (..) NON ART REALITY, to be grasped by all peoples, not only critics (..) FUSE the cadres of cultural, social and political revolutionaries into united front and action”. However, although Left-leaning thinking was projected here, it seems that neither Fluxus nor any other type of avant-garde, in truth, moved any closer to the masses, not even in the sense of the leninist “Art belongs to the people!”. It seems one has to agree with Nam June Paik’s statement that “Fluxus is a condition of the soul”. “Fluxing” was more reminiscent of the Beatnik lifestyle. Fragments of reality and mementoes were collected there, which actually brought the most joy to the same “members of the family”. They began to produce, for example, fluxboxes into which they placed a variety of junk, which all together expressed some message. Similarly to the way that we may regard our deceased grandmother’s little chest of jewellery and keepsakes with deep sentiment. But what should the “simple observer” feel? Although even here, the Fluxists knew how to stimulate a kind of turmoil that would affect every viewer. For example, A Flux Suicide Kit fluxbox made by Ben Vautier in 1966 with a razorblade, cords, soap, poison and other accessories for the suicide event. In 1963, George Maciunas left his US army job for reasons of health and returned to New York. There he established a Fluxus headquarters, which would “ensure the distribution of Flux products at Flux shops or through Flux mail-order catalogues and Flux warehouses. It would ensure Flux copyright protection, a collective newspaper, a Flux Housing Cooperative and frequently revised lists of Fluxus incorporated “workers””. About 50,000 dollars was invested in this venture, but it all went up in smoke, as “we weren’t even able to sell a 50 cent postage stamp...”. The cooperative housing project which tried to provide workshops for impecunious artists in New York’s famous Soho (South of Houston street) district, in cast-iron building lofts, was a little more successful. At first they had to avoid the attentions of police and other authorities, as this once industrial district wasn’t meant to be used for housing. Supposedly this could all be interpreted as a “fluxing” avant-gardist attempt to prove the viability of their socialist concept and idealistic principles in practice, although at times it took on a somewhat naïve pose. Deutschland uber alles After the successes achieved in the Bundesrepublik, the New York Fluxus changed into a more broadly-based international art process with new activists and centres in many countries around the world. But the most powerful, so it seems, developed in Germany itself. There the main Fluxists were, for example, the former Hitlerjugend and volunteer Luftwaffe pilot, but now Düsseldorf Art Academy’s most Left-wing professor, European avant-garde giant Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), or even multimedia artist Wolf Vostell (1932–1998) and others. Observers noted that the German Fluxus was much more sombre, heavier, harsh and politicized, and that there wasn’t any room left for a smile, just accusations levelled against capitalism and the bourgeoisie. In this context we should also mention a Latvian – the Liepāja-born Valdis Āboliņš (1939–1984), architect, Mail Artist, art historian and Fluxist, and later Executive Director of the West Berlin NGBK (Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst). In the early 1960s he was still studying at the Aachen Technical School. He then managed a gallery at Aachen and became actively involved with the Fluxus movement. During this period he collaborated with nearly all of the leaders of the German avant-garde: Wolf Vostell, Jorg Immendorff and Nam June Paik, and in 1964 took part in a joint action with Joseph Beuys. So it wasn’t only the Lithuanians... The seriousness of the joke principle It’s worth remembering that Fluxus, as opposed to Dada, arose in a completely different social climate and operated in a vastly different society and economic environment. The background to Dada was war and blood, an economic crisis and a crisis in bourgeois culture, and the dawning of all kinds of socialist order with the illusion of salvation... For their part, the Fluxists blossomed in the greenhouse of consumer society, at a time when capitalist economies were flour-ishing. Somewhere, a little further away in the background there was a war raging in Vietnam, but it wasn’t nearly as close as the First strong catalyst for a tsunami-like upheaval and reappraisal of all values, and the almost regular attempt to deal with the damned bourgeois hypocrisy and “culture”. The Fluxus era activities culminated to some extent in 1968, during a period of youth revolution which marked some sort of boundary, a change in the model of behaviour and paradigm throughout Western society, chiefly in France, West Germany, England and the USA. Up till then, society viewed avant-gardism more as a “public enemy”, but after 1968 it could see some sort of alternative in it, even a cooperation partner. Because right alongside with it, the mass populace had already gained some experience of “free love” and the “fight for peace”. In describing the Fluxus movement, George Maciunas’ close collaborator and the creator of the concept of intermedia Dick Higgins wrote: “Fluxus is not a moment in history, or an art movement. Fluxus is a way of doing things, a tradition, and a way of life and death. Fluxus should be recognized as an idea and a potential for social change. The research programme of the Fluxus laboratory: globalism, the unity of art and life, intermedia, experimentalism, chance, playfulness, simplicity, musicality. (..) Fluxus likes to see what happens when different forms of art and media intersect. They use found and everyday objects, sounds, images and texts to create new combinations of objects, sounds, images and texts. Fluxus works are simple. The art is small, the texts are short, and the performances are brief. Fluxus is fun. Humour has always been an important element in Fluxus.” The Fluxists, similarly to the Dadaists, for example, had a heigh-tened feeling of relativity, and they, too, didn’t mess around with “beauty” and “plasticity” as if they were a permanent element of aesthetics and art. Here we can discover a great similarity to the Conceptualism which was cultivated in the 1970s. Fluxus, with its buffoonery, theatrical “shallowness” and the jokes, fooling around, laughter and mockery of the partying crowd, was in direct contrast to modernist art of the same period, mainly abstract aestheticism, respectability and a heightened seriousness, as well as the newly emerging pop art, gaining from irrational consumerism not inspiration, but a cause for harsh criticism and provocation. Because pop art really behaves like a girl “without complexes”, shamelessly exploiting and parodying consumer society status symbols, showing off with its “admirers” and without even trying to escape money’s sweet embrace. Fluxus appeared to ignore all of this and developed also marginal and emphatically non-commercial forms of expression in its art. At least of the kind which allowed any dilettante, amateur and art lover “from society at large” to join the “club”. All sorts of bits and pieces, junk, Fluxbox and Mail Art objects etc. didn’t require any specialised knowledge. As Andy Warhol said – anyone can be world-famous for 15 minutes... Whether it’s by destroying a piano, or by wiggling their posterior like Yoko Ono. Inter alia the view exists that it was specifically the fervour of Fluxus and those two delicate posterior hemispheres which destroyed the otherwise harmonious Beatles group. In any case, it all began with John Lennon’s visit to a Yoko Ono exhibition, where he spotted a fascinating exhibit – the white stairs. Climbing up the stairs, one could pick up a magnifying glass and take a look at something on the ceiling. The word YES was written there. P. S. George Maciunas was overcome by cancer. He died in Boston and was interred in New York. “Art must resolve the penultimate issues. It doesn’t get to solve the last ones.” (Dmitri Prigov) /Translator into English: Uldis Brūns/ | |

| go back | |