|

|

| The stopper is out! Laine Kristberga, Film and Art Historian A conversation with the artist Ieva Epnere | |

| The works of Ieva Epnere may be read as palimpsests: a viewer will notice both an ethnographic investigation revolving around contemporary man and culture, and an anthropological interest in various social groups – pregnant women, children, teenagers, and elderly people. The quest for identity is also evident: what it means to be both an artist and a mother, and at the same time not to lose one’s freedom to think and to create. Ieva observes the periphery – small towns, housing estates, suburbs – and is interested in the ordinary citizen, trying to find out whether the environment puts its stamp on a person. According to what she has told us, it can be concluded that the opportunity to spend countless amazing summers in the countryside together with her innovative grandfather and grandmother has been the factor that has most affected the artist’s own perspective of the world and her visual language. To Ieva’s question as to why we remember some things, whilst others are forgotten, we could answer: because our memory is selective, it is closely related to the imagination and blurs with images from the past. And imagination is the thing that enables an artist to see the extraordinary even in the mundane. | |

Ieva Epnere. 2012 Photo: Kristaps Epners | |

| Laine Kristberga: First, I guess, it was Andrejs Grants’ photography workshops where you became more familiar with photography as a medium. What was the most valuable lesson you learnt there? Ieva Epnere: I started to attend Grants’ studio for rather pragmatic reasons – because I had started to use photography in silkscreen works. But in the end it all turned out completely differently! Andrejs Grants opened up for me a totally different world. Pretty soon I understood that photography is my language, which I can use to tell stories about people, relationships and the time we are living in. From Grants I came to know Bill Viola. When I saw Viola’s works for the first time, it occurred to me that I could also try to work with video. After my 4 year – at the time I was studying at the Department of Textile Art – I took the decision to transfer to the Department of Visual Communication. L.K.: Are there any other teachers or artists who have had a profound impact on your creative activities? I.E.: The first work that had an impact on me in photography was Robert Frank’s work Americans. Later I discovered Diane Arbus, whose works are my favourites, I guess. Werner Herzog’s film ‘The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser’ also left a profound impression. There was one episode with wind playing in the leaves of trees, it was incredible! Then there was the artist Fiona Tan and her installation Countenance, made in 2002. She created this work referring to August Sander’s People of the 20 Century, and her intention was to show how people have changed from Sander’s times. Relatively recently – four years ago – I came upon the Argentinian video artist Mika Rottenberg. Music and film are also sources of inspiration for me. At the age of fifteen I discovered Laurie Anderson. I also love the works of Dutch photo and video artist Rineke Deikstra. As regards Latvian artists, Evelīna Deičmane’s works are worthy of notice, I think. L.K.: How do you usually choose a topic and subjects for your works? Is it a chance occurrence, for instance, when you notice some particular type who seems interesting, or is it that first there is a concept which is then followed by the implementation of the idea? I.E.: I am against planned out, worked out art. Of course you need to have a clear vision, but I usually go with the flow and am open to all kinds of turns. Quite often the path from idea to completed work can be a long one, it could take months or even years. Often you start with one intention, but whilst working something unexpected happens that may take the artwork in a completely different direction and quality. You shouldn’t restrict yourself! In many instances a seemingly insignificant accident can play a major role. I have always liked to observe people and their mutual relationships, their behaviour. There have been occasions when a situation I’ve seen on public transport stays on my mind, and it may actually serve as a basis for the next new work. L.K.: So meeting with the main character of the video installation Zenta was probably accidental as well... I.E.: My husband was working on the design of a catalogue which was to do with European funding for the development of Latgale. Because of this project he had to go to Latgale, together with the contractor, but on their way back they visited Zenta, a relative of the project manager. Kristaps took two photos, and in the evening showed me Zenta’s house. And then I couldn’t get her out of my head... Later Inese Baranovska asked me to make a work for the exhibition Nature. Environment. Man. 1984–2004, and I had no doubt that this would be a story about Zenta. In the same way, it was chance that led me to the inhabitants of an old people’s home in Iceland. During my residency in Iceland, I met a Latvian woman who had moved there because of love. She worked at an old people’s home, and one evening she took me along with her. I instantly liked the atmosphere in the home, and asked for permission to take photographs. Somehow it seemed that the people living there were more satisfied with life than the inhabitants of old people’s homes in Latvia... | |

Ieva Epnere. Untitled. Photograph from the series The Green Land. 2010 | |

| L.K.: You take photographs with a film camera and use digital only for drafts, if I understand correctly. Why do you choose to do that? Is it the aesthetics of the shot which occurs when photographing with a film camera that you like better? Is it the expressiveness, depth, cinematic visuality? I.E.: My first camera was a ‘Zenit’. At the time when I became interested in photography and when I began taking photographs, digital cameras weren’t around. Initially I took pictures with a 35 mm film camera, later I tried a medium format camera, and I’m still using it. I like working with film, I like the process and the quality of the image. I have taken photos with a digital camera as well, but usually I’m not satisfied with the result. L.K.: What factors do you take into account when making a decision about whether to use colour or black-and-white photography for a work? Which do you prefer? I.E.: Often when I start working on a new series I take photographs both with black-and-white and colour film. Later I make test photos and compare which ones are better. Mostly I choose colour. In my works light and the colour nuances are very important. I don’t want to excessively aestheticize the image, I’m interested in the particular time we are experiencing now. Colour can speak more. Black-and-white is more abstract, and there are occasions when I want to blur the boundaries between time, as, for example, in the Circus series. L.K.: Is it easy to find and spot the “right” shot? What’s the first thing that you notice? I.E.: I don’t stand there waiting for the right shot, but I begin working. On occasion the first shot from the film has been the right one, yet sometimes I have worked all day long and only at the end, when I’m really tired, the shot just happens. That’s the magic – you never know which one will be the right moment! It’s so unpredictable and intuitive. That’s the reason why I like working with film, because I cannot control it, everything happens naturally. In general, you shouldn’t try too hard. Sometimes I don’t like the photo today, but after a while – and it may be several years – I look at the picture with different eyes and everything falls into place. That’s the right time to exhibit it. L.K.: You once said in an interview that the aesthetic studio shots can be taken at any time and for you it is more important to go outside and document real life. I also remember how the Estonian photo artist Marge Monko once defined beauty in art: “There is no emptier adjective to describe contemporary art than ‘beautiful’: this word says nothing about the inherent idea of the art work. The concept of “beauty” undermines the analysis of art as primarily an intellectual and critical practice, reducing art to the status of interior decoration that is pleasing to the eye.” What is your definition of “beauty” in art? I.E.: This is a very big question. Beauty is our experience, and we have an idea about beauty. Art is a form of communication with the viewer. What I personally look for in art is genuineness and clarity. I seek harmony. We’re continuously looking for answers to the questions that are important to us, and if the work of art has provided an answer, then that must be where the beauty lies. Surely people have a natural drive to discover and experience beauty. | |

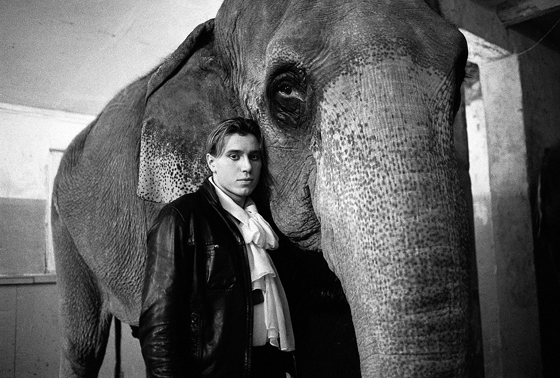

Ieva Epnere. Andrejs Dementjevs-Kornikovs. Photograph from the series Circus. 2006 | |

| L.K.: The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard writes: “If we return to the old home as to a nest, it is because memories are dreams, because the home of other days has become a great image of lost intimacy.” Photography helps you to travel in time, doesn’t it? To return in the past and to revive feelings that have passed? I.E.: Yes, photography is an ideal means for travelling in time. L.K.: What are your most vivid childhood memories, the sunniest moments? I.E.: There’s a great many of them. Mostly memories from the time I spent in the countryside. I had fantastic grandparents, many memories relate to them. My grandfather and grandmother lived together for 60 years! For example, when grandpa was working at the furthest end of the garden, there was a special button in the kitchen that grandma could press to let him know that he must come in for lunch. The signal must have been heard all over the neighbourhood, because our neighbours always knew that Rob is having lunch now... He also had a system for the mail. Whenever the postman dropped a newspaper into the post box, a light flashed up by the bedside. Because, on cold winter mornings, who wants to go outdoors to check whether the mail has arrived? Grandpa was an electrician and he also invented designs for electric heaters. Some of them were particular examples. L.K.: Does the doll Rita also feature in these memories? I.E.: Rita was my first series. It was made the year my grandmother died. It was the end of winter and we, the family, went to the countryside to do chores around the house, to do some spring-cleaning. While sorting through things I stumbled across this old doll which dredged up memories, and the decision to photograph the doll as a guide through the garden of our house was on impulse. I’d call the entire process grief therapy. L.K.: Judging by your works, the feeling and subject of home is of importance to you. What is the definition of home, from your point of view? Now, when living in Belgium, do you see home in a different light? I.E.: My family is my home. We came here all together, so at the moment my feeling of home is here, in Belgium. L.K.: What else has changed since moving to Belgium? Would you say that studies abroad are a kind of facilitating factor in an artist’s growth? An opportunity to distance oneself from Latvia and, perhaps, to look at many things, including yourself, differently? I.E.: Of course it is facilitating! Probably this year and a half has been the best thing that could have happened in my creative life. I feel that the stopper is out, I feel liberated, whereas in Riga it was difficult. To be honest, I found oppressive the things that go on in the little art world of Latvia. I needed to come to Belgium in order to understand what I want to do in Latvia, what ideas to realize. Here I can think and work. In Riga I had to put in twice as much effort and often I began to wonder why I’m actually doing it all... Since I’ve been in Ghent, nothing like that ever crosses my mind – I want to work! Here I get feedback. L.K.: What are your studies at HISK like? Is the learning process different than at the Latvian Academy of Art? I.E.: It’s a postgraduate programme. In general, HISK is a special place. You cannot really call it a school. It’s an institute, a platform for various media. We’re all so different here! Each year only twelve students are accepted, and the programme lasts for two years. This year there’s a sculptress, a painter, a video artist, a sound artist and several photographers studying in the programme. We are not restricted in any way and can experiment with various media. Each of us can focus on our individual work, and we all have been given our own studios. All kinds of guest lecturers visit us on a regular basis – curators, critics, artists, etc. We can meet them and discuss our work in one-to-one sessions. Afterwards we receive a report and an evaluation in writing. HISK is the right place to study if you want to experiment! Here they organise creative workshops, for example, related to sound, video, micro-robotics, etc. This year there will be an interesting co-project with young composers from four countries. We also attend significant art events, for instance, we visited the Istanbul Biennale in Turkey and the Diane Arbus exhibition in Paris. L.K.: Has anything changed in your artistic production since the birth of your daughter? I.E.: When Lūcija was born, I had a year to think over many things. I understood that I couldn’t live without art – I know, that sounds banal. Before Lūcija, I had been in several artist residency programmes abroad, but mostly they lasted for two months. Every time I came home, I had the feeling of being unsatisfied, a person who’s only half-eaten, and I felt that I wanted to study more. After a year spent at home, I decided to apply for some of the postgraduate programmes. And here I am! Lūcija inspires and mobilizes me. When she was born, I started working on my work The Green Land. It came about as a result of the long walks around Vaiņode. Visiting and revisiting the same places over and over again, I got the idea to photograph Vaiņode, to work with the local residents. L.K.: In reviews about The Green Land it is said that this work is your quest for and exploration of identity. Is it really like that? How would you define your identity as an artist? I.E.: The issue of identity is on my mind all the time. My mother is Latvian and my father is Russian, so I have two temperaments co-habiting in me, which probably affects my creative working process. All in all – The Green Land is a significant work for me, because in this work I changed my strategy in photography: I started balancing between staged and documentary photography. L.K.: Often in video art artists observe themselves in their search for identity, they become obsessed with self-analysis, and use their own bodies or images that to some extent would articulate or represent themselves. You don’t participate in your video works – if “only” through the fact of authorship. Is there an explanation for that? I.E.: I don’t think that in order to pursue a quest for your identity the body or image must be definitely used. It can be revealed also through your perception of the world. | |

Ieva Epnere. Photography from the series 1 September. 2011 | |

| L.K.: Would the quote of Jean-Luc Godard be more applicable to the strategy of your work, namely, that the auto-portrait of an artist should reflect not the artist, but instead – what he or she perceives, sees, notices, observes? I.E.: Possibly. L.K.: How did you come to the work Notes of a Travelling Circus? Why does the circus fascinate you? I.E.: It started accidentally in 2004, when I participated in a competition organised by Sony. The topic of the competition was ‘Time’, and it occurred to me that I could photograph the moment before a circus artist enters the arena. I don’t know where I got the idea, I simply had it and that’s all! I was awarded first prize in the competition and that’s how I got a digital camera in my hands for the first time. In fact, before I started to photograph the circus, the last time I had visited Riga circus was when I was in primary school. After the Sony competition I returned to the circus repeatedly, in order to continue to take photos, and later I joined the troupe of the travelling circus Allez on their tour around the small towns of Latvia. That’s how Notes of a Travelling Circus came into being. I was interested in finding out why nowadays people still get engaged in circus art, and whether people still believe in the wonder of the circus. L.K.: The theoretician Laura Mulvey writes that “one way to discover the attributes and self-definition of a “high culture” is through its opposite, the low culture that represents what the dominant is not”. And the circus is considered to be “low” art! I remember in Bulgakov’s story ‘Heart of a Dog’, Doctor Preobrazhensky couldn’t understand what it was that the proletarian Sharikov found so appealing in circus performances. He himself only went to the opera. Does the circus interest you as a form of “low” art? I.E.: I didn’t start taking photos of the circus because I was interested in it as a form of art. Riga circus is one of the oldest circus establishments in Europe, it has a particular atmosphere. I am fascinated by the ambiance that prevails in the circus building and backstage during rehearsals. You cannot describe it in words, it must be experienced! I don’t wish to distinguish circus as “low” art, especially now that I have become acquainted with the people who work there. L.K.: But what about seeing the circus backstage – doesn’t it make you realize that circus art is not only ancient, but also outdated? Animals are being exploited... That photograph with the elephant in chains is so sad. I.E.: Yes, it does. In Europe no one works with animals any more. Riga circus is that rare place where you can still see shows with animals. In the performances of the Moscow and Belarus circus troupes, too, animals are involved. L.K.: In your work Moments of Happiness you document people with absorbing pastimes. How did you manage to find the subjects for the work? I.E.: This work was created for the exhibition Jukas. As it so often happens, the idea came from “real life” stories. I had a conversation with one of our family friends and he admitted that the thing that made him really happy was mowing the lawn, and that he couldn’t wait for spring. This conversation inspired me to talk to other people to find out what their moments of happiness were. I was interested in speaking to people from as diverse occupations as possible – an accountant, a film director, a lawyer, etc. – and to ask what their “strange” enthusiasms were. Each one of us has something like that. L.K.: In several of your works an anthropological interest in the human being can be noticed, for example, in the three-part project about teenagers in Reykjavik, Dusseldorf and Riga. What is it that attracts you to the adolescent years? I.E.: Yes, the first series was done in Iceland. When I applied for the residency scholarship, I had to write a project proposal. I thought that one way of getting to know a completely foreign country is through conversations with young people. So that’s how it started. The next series was in Dusseldorf, and after that in Riga. For quite a long time I worked as a teacher of visual arts at the Riga Dome Choir School. My school experience, definitely, encouraged me to work on these series. Why the adolescent years? In my opinion, it’s the age when a person makes their first choices. It’s a very fragile time, when many things can affect personality, the “wrong” friends, idols, etc. L.K.: Among your latest works there’s an artist portrait series titled The Artists (2011), and 1 September (2011). How did the project The Artists come to be realised? I.E.: In autumn 2010, the art historian Anita Vanaga approached me and asked me to work on a series of portraits of artists that feature in Guntis Belēvičs’ collection; this was to be included in a book accompanying the exhibition Blīvā telpa (‘Thickspace’). Later on in the process we had the idea to exhibit the photographs as well. I spent several months working on the series. A small portion I managed to photograph before going to Belgium, then the following spring and summer I came back to Latvia in order to continue taking photos. In total I shot seventy portraits. It was very intensive work! Generally I’m very grateful for this opportunity to photograph Latvian artists – many of the encounters were quite special. L.K.: And what about the school pupils on 1 September – is it a continuation of the previously examined subject of the housing estate? Do the surroundings in the background play an important role? I.E.: In the summer of 2011, Ieva Stūre and Kristīne Želve asked me to take part in [the event] White Night. Because their “bit” was Purvciems [the suburb of Riga] and the theme was Purchiks’ Gallery of Fame, I got an idea to photograph the children of Purvciems on 1 September – the day when school age children get dressed up and go along to celebrate their first day of school. I was really surprised that so little has changed since I went to school myself: hair is still done up with white ribbons, hands are full with bouquets of gladiolus and asters etc. I was also fascinated by the way the children posed for me – like little grown-ups... L.K.: It’s interesting that elsewhere in the world, for example, in Great Britain, celebrations of knowledge like this don’t exist. Each year school starts on a different date, it’s the beginning of September, but not definitely 1 September, and pupils aren’t expected to come to school wearing their best clothes. Why does 1 September interest you? I.E.: Because, to my mind, it is something so peculiar that still continues to be done in Latvia. It truly is a phenomenon that is not practised anywhere else in Europe. When I exhibited this work in Ghent, viewers asked whether it was a graduation, or a First Communion. L.K.: What are you working on at the moment? I.E.: Currently I’m working on several projects at once. One of them is titled Their Flemish Landscapes, which I started in spring last year. In this project I ask Flemings to take me to a place that, in their opinion, would be typical of a Flemish landscape. Another work that I have been working on is titled Mamma (‘Mother’). This work resulted from my own experience of being a mother, and my closest friends are also mums – one of them has even got three kids! Since I’ve been living in Belgium, the question of being a mother and an artist has become a very topical issue for me. How to distribute time and energy, how to be a good mother without losing the freedom to think and create. Here, in Belgium, many artists choose a life without children, or postpone it till some distant future. Of course there are exceptions, too. Because most of my female friends are creative people – there’s a textile artist, a graphic artist, and a film director – I thought it was high time that we should discuss this subject. It’s a topic talked about reluctantly, because it goes without saying that an artist needs silence and time for himself or herself, but if you have a child, you can’t be saying “Wait!” all the time. I started this series in summer last year, when I’d already spent half a year in Ghent. When I returned to Latvia, I asked “my” mums to pose for photos. Now I’ve realised that there are a number of levels to this work. I still don’t know what scope it will have, perhaps it won’t be limited to Latvian mums – artists only. In the near future I’m also going to start work on a sound and photography installation, to make a work that will be exhibited in the urban environment of the Belgian town Genk. Then in March there’s a documentary photography project Middle Town: Picturing the Unspectacular. The first part of the project will take place in Turkey, in Trabzon. There will be four participants from Latvia, four from Turkey, and four from other EU countries. L.K.: Have there been any funny situations in your artistic experience, after all, your projects are very social? I.E.: Yes, there have been. For example in Dusseldorf, while I was photographing teenagers, one of the models – an Iranian guy – started dancing on the bed, in all seriousness. What do I do now, I thought, I was dying to burst out laughing – it’s easy to set me off and usually I can’t stop myself! Or there was that situation during the circus period. I’d arranged to take photos of the hyena tamer Viktors Ņikuļins at rehearsal. At the time I was expecting Lūcija and was in the fifth month of pregnancy. When I got to the circus, I saw a protective mesh around the arena – all in good order in terms of health and safety. Inside the cage, the three hyenas were sitting on their pedestals and hissing furiously. The tamer was all smiles and greeted me: Good day, shall we begin? To put it briefly, he was inviting me inside the arena, on the other side of the mesh. My legs went numb with fear, but a deal is a deal! I still remember that feeling today. But I got a good picture. Ieva Epnere (b. 1977) recognised as a photo and video artist. Graduated from the Art Academy of Latvia with a BA degree in Textile Art and a Master’s degree in Visual Communication. Has also participated in several artist residency programmes abroad and various international creative workshops. Currently studying in a postgraduate programme at the Belgium Art Institute HISK (Hoger Instituut voor Schone Kunsten). Solo shows: Notes of a Travelling Circus (Goethe Institute, Riga, 2004); Encounters (Atelier Hoeherweg, Dusseldorf, Germany, 2006); Darbi [‘Works’] (Kulturforum Alte Post, Neuss, Germany, 2009); The Green Land (kim?, 2010). Group exhibitions: Nature. Environment. Man. 1984–2004 (Arsenals, 2004); European Night (festival Les Recontres D’Arles, Arles, France, 2008); Endlich Schnee in den Alpen (Gallery Maerz, Linz, Austria, 2008), Life in the Garden (Giedre Bartelt Gallery, Berlin, Germany, 2009), Reality Check (Reykjavík Art Festival, Reykjavík, Iceland, 2010); Thickspace (Arsenals, 2011); Invite Someone (Galerie Kunst-Zicht, Gent, Belgium, 2011), Fat Birds Don’t Fly (Netwerk, Aalst, Belgium, 2012). /Translator into English: Laine Kristberga/ | |

| go back | |