|

|

| A review room and three artists Eglė Juocevičiūtė, Art Critic, Curator | |

| Since the end of last November the Thursday Review has taken place every Thursday evening at Vartai Gallery in Vilnius. The creative work of a younger generation artist (up to about 25 years of age, although the limit is not strictly adhered to) gets exhaustively inspected during this event in one of the gallery’s halls – in the Review Room. The artist him- or herself, gallery employees and an art critic who publicly introduces those present to the specific artist’s creative activity (at the moment this pleasant task, which we’ll call scouting, is done by us, three scouts: Danutė Gambickaitė, Jolanta Marcišauskytė-Jurašienė and Eglė Juocevičiūtė) take part in the event. The project is intended to get people more acquainted with the new generation of artists, and this introduction is of use both to the gallery as well as the overall Lithuanian art scene. The last exhibitions in the ARTKOR project space took place in 2010. This was the only space in Vilnius run by art students themselves, and since then it has been possible at times to see young artists at the Vilnius Academy of Art galleries and in the site-specific art projects and exhibitions in former industrial spaces. The Vartai Gallery’s Review Room, obviously, doesn’t offer as much creative freedom as existed at the non-commercial ARTKOR, but it is a more favourable environment for photography, video and installations than the academy galleries with their unclear profiles. This is due to the image of the great contemporary art gallery, as the white cube and the purely technical solutions which have come about due to the gallery’s experience in exhibiting the most diverse contemporary art (dirty technical things often interfere with being able to see something good at exhibitions that are set up in abandoned spaces). And, as opposed to group exhibitions, obviously the artist can show more, and more diverse works here, without having to think about the context of the exhibition’s neighbours. Granted, though, that Vartai is a commercial gallery, and one of the main aims of the review is to promote sales. That’s why, in a scout’s work, in choosing the context in which to reflect the artist’s works, a clash of positions arises between what’s interesting to the Lithuanian cultural community and Lithuanian art buyers. For the latter this review project is still more an educative event, whereas for the artists and for us, the scouts – an experiment. The gallery also looks at Latvia and Estonia, and artists are invited to send in applications if they feel that this offer is interesting. | |

02.02.2012. Justė Venclovaitė | |

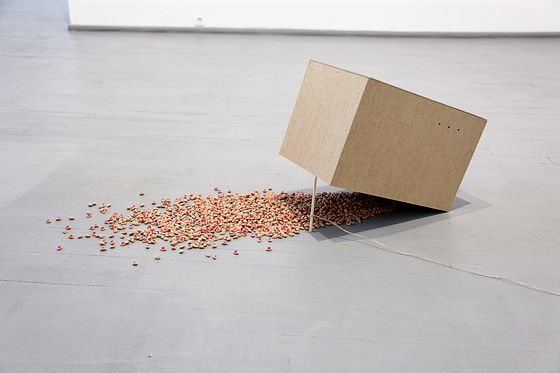

| The February reviews were devoted to three artists: Justė Venclovaitė, Jurgita Žvinklytė and Arnas Anskaitis. They work in different media and create an original aesthetic, and it is this, specifically, which is most often sought in the creative work of young artists. I offer a brief introduction to each one of them here. Justė Venclovaitė Aesthetic exploitation Justė Venclovaitė’s review, the opening of the Do not drop installation took place on 2 February. In 2010, the artist completed a Bachelor of Sculpture study programme at the Vilnius Academy of Art together with an active and interesting group in her year. After their third year of study (in 2009), Valentinas Klimašauskas invited her and the students from her year to take part in the Contemporary Art Centre’s Jumping and Loops exhibition. Their diploma exhibition, called Pakalnės 2/1 Aludarių – a joint exhibition in an abandoned brewery – also exceeded the requirements which are expected of student diploma works. Still, the originality of Justė Venclovaitė within the framework of the group mentioned as well as in the wider world of Lithuanian installations is created from her hand: she creates from plasticine and clay, pours objects from concrete, plaster and silicone, constructs from organic glass, draws and paints. The results of these handiworks become a part of the artist’s wider projects. Whatever her means of expression may be, all of her creative work is united by a playing around with the appearance of the visual object or subject and its linguistic, as well as anthropological meaning. The works Kalba (‘Language’, video, 10:11, 2008) and Pudeliai, (‘Poodles’, sculptural installation, 2008), which were exhibited at the Jumping and Loops exhibition could be mentioned here. A language teaching phenomenon is examined in ‘Language’, namely, that the text (both what’s written as well as heard) is only a means for ex-plaining the grammatical structure, but its meaning – the situation or stories – are not at all important (they only have to be logical and politically correct). That’s why in ‘Language’, Venclovaitė replaces the words with various items and, by matching these with the texts heard in the background, texts which are meant for acquiring the English language, creates a question and answer, a principal clause and a subordinate clause, a request and an acceptance or a refusal of these... Two kinds of items are used – everyday items which can be bought at the nearest shop and can be found in every home, and decorative elements and souvenirs from the author’s home, which indicate individual personal stories. These collective and personal items are then composed in a variety of ways into visual “statements”. She has poured the three ‘Poodles’ from concrete – three poodle snouts with their teeth bared to varying degrees, which are meant for hanging on a wall. Here Venclovaitė plays with the tradition of decorating a home with stuffed animal heads, as well as the poodle as an aesthetic concept. The poodle is a dog which has lost its “doggishness” (protecting and providing a feeling of emotional security), as it’s mainly kept for its beauty. The heads of stags and wild boars are also hung on the wall for their beauty, probably more so in order to increase one’s feeling of power, or to remind one of how powerful the vanquished once was, the stuffed heads being set in threatening poses – baring their teeth and with their jaws open. In this way Venclovaitė also endows her concrete poodle with menace, mocking its beauty, but maybe restoring a little bit of its free will as well. According to the author, the same interest in the zoo shop aesthetic could be seen in the Do not drop installation created for the Vartai Gallery’s Thursday Review Room, as in her bachelor’s project ABC123 (2010). Six objects were placed on high white pedestals in this installation: an animal head from the cat family poured from white silicone, with its fangs bared, a lower jaw from an unidentified animal, a column with white cords wound around it meant for cats to sharpen their claws, a photograph of a dog walking in the ruins of the Acropolis in Athens, a muzzle and a model of a classicism building constructed from organic glass and filled with milk. All of the objects, except for the “holey” muzzle are white, and that unites them visually, but the viewer is forced to make sense of the connection – to solve the rebus. In my view a number of layers of meaning arise, through which connections between the objects develop: classicism – a certain principle about looking at the world and its control, as well as an architectural style; archaeology – classicism being based on its discoveries; the cat – both as an attribute of the wild world, as well as a tame domestic animal. The Do not drop installation was quite motley compared to ABC123. This was made up of four organic glass pipes, similar to flourescent lights and filled with bird seed, fixed to a wall at an angle; a framed piece of cardboard which the author had cut out of some box she’d found on a Vilnius street with writing on it attesting to the fact that live fish had been transported in it from Jakarta, Indonesia; a papier-mache copy of a frog – dissection model used in a biology class. Primitive traps had been placed on the floor – a box resting on a wooden dowel: to catch something with traps like these, one has to wait for the victim to crawl under the box, and then the string tied to the dowel must be pulled. There were lots of plum stones next to the box (they are seeds as well), and an eye had been drawn on each of them – there’s a theory that birds are frightened of these and won’t eat something that has an eye on it, or patterns similar to the iris of an eye. That’s why butterflies which specifically have an “eye” on each wing have long and good lives. In the ABC123 work, Venclovaite raised the zoo shop aesthetic to the canons of classicism, whereas in Do not drop this aesthetic was closer to the canons of the beauty of contemporary art. Although the terms “contemporary art” and “beauty”, having been strung into the same sentence, on first glance arouse an ironic smirk, Venclovaitė draws attention toward the direction of the minimalist aesthetic in art, to the purity of its images, which designers who make items for animals, in a way, also take as an example. The animal and its life serve the human as another category of aesthetics. | |

Jurgita Žvinklytė. Riddle: Where is the Centre of the Earth? Answer: Where you, yourself are standing. Performance. 2011 | |

| Jurgita Žvinklytė Unnoticable psycho-geographic experiences Jurgita Žvinklītė’s work Minklė: kur žemės vidurys? Atsakymas: kur pats stovi [‘Riddle: Where is the Centre of the Earth? Answer: Where you, yourself are standing’] was put forward for the review on 9 February. Jurgita completed her Master’s studies in Professor Henrik B. Andersen’s class in 2011. This Danish artist has been lecturing at the Vilnius Academy of Art Sculpture Department since 2008, and within the context of the academy, the direction of studies in his class is consistently interdisciplinary. During her studies Jurgita developed an idea borrowed partly from Fluxus: a performance structure. She constructed structures (explicitly geometrical or at first glance chaotic) from short and long lines which transformed into a movement/dance choreography. The length of the line depended on whether the line was meant for a foot, a hand or the whole lower arm from the tips of the fingers to the elbow. She also created such a structure – hands and arms – on the Vartai Gallery Review Room wall. Even though the structure seems improvised, it requires fairly accurate calculation and planning – the arm cannot be pulled away from the wall, it can only be turned, and that’s why Jurgita has to foresee in advance how to get out of the deadlock which the viewer can reach in walking through Jurgita’s paths “with his/her hands”. Obviously, the structures are best suited to peope who are of Jurgita’s height, and whose arms and legs are the same lengths as the artist’s own. Jurgita’s master’s degree work Minklė: kur žemės vidurys? Atsakymas: kur pats stovi came about from the development of this structure and Jurgita’s desire to go beyond this. The Vilnius Academy of Art is located not far from Kalnai Park, where one of the symbols of Vilnius – the Three Crosses sculpture, as well as the stadium and dance square where folk dancing groups perform during folklore festivals, are located. So that the large group doesn’t get lost in the square, the initial stopping and (probably) turning points are marked on the ground with various signs. This structure, for choreography, became the place for Jurgita’s performance, in which she extended the “distance measurement”, now using her full height as the measurement. She squatted, sat and lay down between these signs for ten minutes on ten days (the time was measured with the artist’s internal clock, which meant that the activity could last for eight or even thirteen minutes) from 10 am (the ten was chosen as the common measurement threshold, like a defined unit). By wonderful coincidence, the distances between the signs on the dance square corresponded to the proportions of Jurgita’s body. She marked her movements across the square by drawing lines with chalk, but after the tenth performance on 10 June, the structure which had been drawn over ten days was washed away by a heavy downpour. The 10 (2011, 20’23”) video which was shown in the Review Room was made from the video documentation of all ten performances. Minklė can be seen as a pseudo-geographic experiment, as a play with an archaic, or maybe relativistic understanding of the world: there’s no more world for you than you, yourself, see and are able to perceive. Jurgita’s other performances, which have come about in different contexts, are worthy of attention, too. Jurgita created a site-specific poetic performance for a one day project – a dedication to gegužės7 (7 May, Danutė Gambickaitė, Jolanta Marcišauskytė-Jurašienė and Egle Jocevičytė were the curators). gegužės7 (2011) took place at the Vileišis’ home, which was built in 1906 by Petrs Vileišis, a conservator of the Lithuanian language and culture. One building in this ensemble of buildings was meant for the Vileišis family, another for a newspaper printing press and for cultural events (the first Lithuanian art exhibition took place there), and there were also rooms for other people working in Lithuanian culture at the time to stay in. Nowadays, the Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore is located in the building. The Vileišis house is on a hill next to the River Neris, and, through collecting materials and listening to stories about the lives of the Vileišis family, Jurgita’s attention was drawn to the fact that the Vileišis, sitting on the terrace of their home, used to hear young people singing as they sailed along the river; if the Vileišis particularly liked the song, they invited the singers to join them on the terrace to sing for a fee. The plot of land between the river and the house has changed since the early 20 century, and now an asphalt road leads there, with a different building being constructed for this same institute. Still, Jurgita decided to repeat the songs and to try listening to them from the Vileišis’ terrace. She invited the Kaukaras post-folklore ensemble to perform the musical performance of Skambanti Neris (‘Reverberant Neris’), putting the ensemble participants on the other side of the river (in the interests of safety she didn’t sit them in a boat), and visitors to gegužės7, standing on the terrace, could hear the songs, to a greater or lesser degree (depending on the wind), that were being sung. The Minklė psycho-geographic experience for the senses was mainly Jurgita’s own experience, the viewers were and remained viewers, even when the June morning sounds and Jurgita’s rhythmic movement magic was successful, whereas in ‘Reverberant Neris’ she created an experience and provided a May evening of singing for others (as she was on the opposite side of the river with the Kaukaras singers). It was a very delicate performance, as one had to listen in and feel it, and it was specifically this which made it memorable. The Hugh Granto savirefleksija (‘Hugh Grant’s Self-reflection’, 2011)1 internet experiment, which was offered to the public in May and June 2011 in the Editing Spaces project which took place in Vilnius, was completely different and revealed Jurgita’s ironic side. British actor Hugh Grant was selected completely randomly: having watched one of his films, Jurgita decided to search for information about the actor on the internet and discovered the broad fanbase there. Wanting to play around with both the phenomenon of being a fan, as well as with the possibilities that the internet provided for fans, Jurgita created another (there were many hundreds of them already) Hugh Grant profile on a social network. This profile differed from the others through the fact that only other Hugh Grants could become friends of this “Hugh Grant”, and that’s why this wall appeared to be quite schizophrenic: “Hugh Grant added another photo of Hugh Grant” and “Hugh Grant likes this”, as well as tens of Hugh Grants, who chatted about “this”, differed from each other with various profile pictures. If it’s possible to view the internet as a breeding ground in which sociological problems can arise and be solved, then this project was a great psycho-sociological example of how the boundaries of identity disappear completely. It’s interesting that in all of Jurgita’s performances one thing remains, a position that may have been taken unwittingly: one who isn’t aware of them may not even notice these performances. | |

Arnas Anskaitis. yra. Installation. 2011 | |

| Arnas Anskaitis Spaces, times and connections On 17 February Vartai Gallery celebrated its twenty first birthday and introduced the works of Arnas Anskaitis. Arnas is currently studying for a Master’s degree at the Vilnius Academy of Art Department of Photography and Media Art. To my mind, his originality among his generation comes from his powerful imagination, which the artist puts to work when it comes to choosing the most appropriate media for his project – he doesn’t restrict himself to a particular craft (in his case this would be photography and filming, as well as work with scenes that have been photographed and filmed). If he does, however, use his craft, then he uses its possibilities to the maximum degree: he creates non-scene reproductions of no images and films of time, in which nothing happens. In other cases his project can be enlivened by a choir and people who carve letters into stone. In writing “photography of no image”, I mean his project Fotografija kaip reikšminis paviršius. 1m2 galerijos (‘Photography as the Surface of Meaning. 1m2 Gallery’, 2009), in which Arnas photographed one square metre in all of the Vilnius buildings in which contemporary art is exhibited, and reproduced these square metres in square metre imprints. In 1976, Brian O‘Doherty had already declared in his ‘Inside the White Cube: the Ideology of the Gallery Space’ collection of essays that even after getting rid of and painting over the signs from installations which had changed the gallery space, these signs were maintained in the gallery walls; a wall’s history doesn’t disappear, but instead only gets richer. So, too, in Arnas’ wall reproductions. If one puts in the effort, one can see the fine signs of the art wall’s history. On the other hand, this work is an illustration of a continuing belief in Lithuania that a gallery provides an artist with walls on which to hang his/her paintings, rather than a communications network. In the recent review at the Vartai Gallery, the square metres reproduced by Arnas from the Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) and Vartai could be seen, and viewers had the opportunity to compare the similar and the different which is characteristic of the walls of the two institutions that organize the most interesting contemporary art exhibitions in Vilnius. In the Kairos (2009) video, Arnas filmed in spaces in which one can’t accurately measure in quantitative chronos time, spaces in which a person remains only as long as necessary, and why time there is measured through the quality of the opportunity and experience – with kairos time. In this video the church and the shower are representative of such spaces – places where a person bares oneself both spiritually and bodily. Both rooms are white and empty. Nothing happens in either space, and that’s why this is a negative kairos, an unused opportunity to bare oneself and change. Arnas used the services of a choir in the Tradicija performance, which took place at the opening of the Akademija exhibition (moderator Vytautas Michelkevičius) at the Akademija Gallery (2010). The Vilnius Academy of Art choir sang the words conjured up by Arnas: Dailioji dailė (literally – ‘Beautiful art’), which reflects the word dailė from the Vilnius Academy of Art name (in Lithuanian Vilniaus dailės akademija), to the tune of the popular congratulatory and “wishing you luck” song Ilgiausių metų (‘Long time’). The word dailė (‘art’) is to make beautiful, or beautification, and operates as a contrast to its synonym menas (‘art’), which Arnas draws out from mintis (‘thought’). The beautifier preparation function is encoded in the name of the institution, and the choir’s costume with its stylized Baltic elements became an illustration of it. This performance could partly be considered as a response to the conditions provided at the Akademija Gallery of the Vilnius Academy of Art (and also as a continuation of the work ‘Photography as the Surface of Meaning’) – one is not allowed to drive nails or drill holes there, and students have to be able to hang all of their art on little hooks hanging from special supports on the ceiling. Arnas’ bachelor’s degree work yra (2011) continued his interest in the mutual connection between words in the Lithuanian language, between the tension the sound of a word and its meaning. He inadvertently found an article by Lithuanian language researchers – amateurs Aleksandras Žarskus and Algirdas Patackas ‘On the Lithuanian Language’s Fern Flower’ (2005), in which the possibility of the sound and recollection of the meaning in the Lithuanian language is looked at: maybe the sound truly still has meaning in the Lithuanian language, and meaning its own sound? These types of dichotomies are held up as examples: būtis and buitis (existence/daily life), nokti and nykti (swell/wither), myluoti and meluoti (to love/to lie), drįsti and drausti (to dare/to forbid). Arnas found the shortest Lithuanian dichotomy contained in one word for his work: if the letter a is emphasized in the word yra, it denotes existence (translated as ‘is’), whereas if the letter y is emphasized, then that same word means ‘extinction’ (literally translated as ‘disintegrating’). Arnas quietly monumentalized this symbol of archaic wisdom and language logic with an inscription in stone (with both emphasis signs) in the new Academy building balcony trimming. The building and the balcony are located in the very heart of Vilnius old town, but obviously only very few of the people who walk along the street there know about the existence of the inscription. Furthermore, the activity itself – inscription in stone – is dichotomous: stone seems to be forever, but the inscription itself is in a way a destroyed and expunged negative, yet we perceive this non-existence as existence. Looking at the inscription from above, it looks as if it has “a line through it”, because a hand support is fixed above it, and in this way the sous rature instrument developed by Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida can be used here: the crossed out word shows its potential non-existence. It is necessary but imprecise, and that’s why the word itself is stated as well as its denial. This condition of deadlock or even bewitched circle operates in all of Arnas’ works, he doesn’t try to change or declare anything: he plays around with the existing situation and highlights its absurdity, or more likely the inseparable connections in everything. /Translator into English: Uldis Brūns/ 1 www.editingspaces.org/index.php?/jurgis-pas | |

| go back | |