|

|

| The transcendence of patience Pēteris Bankovskis, Art Critic Sarmīte Māliņa, Kristaps Kalns. Be Patient 09.02.–18.03.2012. Latvian National Museum of Art, exhibition hall Arsenāls | |

| From 9 February to 18 March the Arsenāls hall was the venue for a collaborative exhibition by Sarmīte Māliņa and Kristapa Kalns – materialised reflections titled Pacieties (‘Be Patient’). In the following passage, familiar to all, from Paul’s Letter to the Galatians (Galatians 5, 22–23) we read: “But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance: against such there is no law.” I dare to go so far as to say that what the artists have achieved fits in among the theological and human virtues listed by Paul, and not only because of the exhibition’s title. Any work by the human spirit, emotions, mind or hands requires patience. Patience is needed to see, notice, compare with one’s experiences, to integrate into feelings and, to use a fashionable contextual word, to appropriate. An exhibition, a display, an achievement brought out into the open (which may be called an installation, if one so wishes) always demands patience – especially if genuine thinking is overwhelmingly present. But it was ever thus: the visitor or viewer cannot read the artists’ minds or participate in what could abstractly be called creative impulses, those concrete moments of inspiration that make us act in a certain way and not otherwise. As in all times and places, here we can only make guesses and try to set off some impulses within ourselves. By following the artists’ invitation to be patient, we can contemplate what the creators have offered and compose our own offering, our own interpretation for personal use. That is what I offer here. | |

Sarmīte Māliņa, Kristaps Kalns. The invitation image of the exhibition Be Patient. 2012 Photo: Kristaps Kalns | |

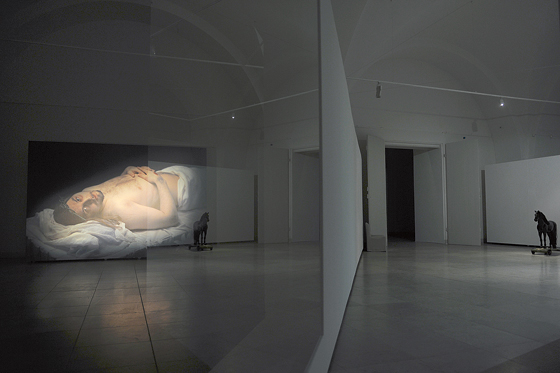

| The exhibition in Arsenāls was opened about two weeks before Ash Wednesday, the start of Lent, and it ended about a fortnight before Easter. There is something in this coincidence with its two week “divergence”. I think that what Māliņa and Kalns offer is a sort of Lent for contemporary people: acceptably direct and unambiguous, but “divergent”, because somehow it seems impossible, unwise or strange not to have this divergence, to do away with reservations or to omit the “what if” comment. Resurrection On entering the exhibition hall, behind a dividing wall organising the space, through mildly hallucinogenic reflections, through a window to another world, I saw the Son at the first moment of Resurrection. The moment not witnessed, neither by the disciples nor the women. The moment when the Father opens His eyes with the power of the Holy Spirit. The eyes are turned towards me, and they ask: “Who are you? What do you want? Which side of the invisible wall are you on?” The horse of fate A black lacquered toy horse with a real horsehair mane and tail: take its lead, put a child on its back and play. But games can be extremely cruel. The depiction of the horse of fate in Arturs Baumanis’ painting does look like a game or a label on a box of sweets. But let us imagine Teodorihs, who had come in the light of truth, hope and love to bring the story of the Resurrection to the Daugava Livonians. Trustingly he waited to see which foot the horse would move first, as this would determine whether the Livonians would kill the stranger or let him live. The Livonians believed in the horse, while Teodorihs had faith in the Higher Being. Can we, today’s Latvians, find an answer as to why Teodorihs remained alive? Perhaps we still choose to believe in childhood toys? Imago Dei Be that as it may, regardless of whether you believe or don’t believe, the artists bring us into the second space – a church with real pews made by students at the Riga Applied Arts High School, which after the exhibition will find a new home in the Mercy of God Catholic Church in Kauguri. Sitting in the pews, we see an altar, or rather two identical altars. Each altar consists of a giant, totally black circle surrounded by a halo of light from an unknown source. While the Apostle says: “No one has ever seen God” (1 John 4, 12), it is written in Genesis that “God created man in His image and likeness” (Genesis 1, 26). What is it that caused the Big Bang, which is currently assumed to have created matter, the universe and everything? Why are we the way we are and not something else? How and why are we thinking about this question today and always have done, forever and ever? Some might say that the point of spiritual and religious beliefs is to try to answer these unanswerable questions, that they are merely instruments, not the essence. But in any case, it all remains a mystery. Two circular black altars in a binary partnership address the brain’s right and left hemispheres, faith and doubt, fear and hope. It is clear that there is something beyond the blackness – otherwise the halo of light wouldn’t be there. But what is it? Perhaps the answer is about me, and the One in whose image I am made. I will find the answer on the other side. | |

Sarmīte Māliņa, Kristaps Kalns. Be Patient. View from the exhibition. 2012 Photo: Kristaps Kalns | |

| Vanitas On leaving the church space, the eyes linger on what looks like an icon in a small glass display case. For the duration of the exhibition, a bouquet of cut flowers is decaying under the glass. The stems, leaves and petals are inexorably overwhelmed by wilting, mould and decomposition. The cut flowers experience a brief pilgrimage towards dust and ashes. The confident Dutch founders of “modern capitalism” in the 16 and 17 century hadn’t yet forgotten about death and the fleetingness of all things, so they commissioned paintings in which impermanence is symbolized by a skull, a candle burning low and fruits and flowers, destined to decay. The modern person “who believes in something or other” doesn’t want to believe in or think about death, and yet strives ceaselessly to increase the average life-span. Sola Scriptura? Many consider that Latvia’s main religious confession is Lutheranism. There are a number of reasons why this belief has come about. Exiting the space for reflection offered by the artists, we still have to visit a black cube-like room with a shiny black lacquered door. Upon entering the room, one is surprised by a disturbing light from what looks like an office ceiling. In the middle of the room on a roughly hewed metal stand there is a book. Of course, we live in a land that was shaped in some way by one of the so-called Book religions. But are these really only the Scriptures? Are they really carved in stone? But it turns out that the marble from which the book is shaped is not unyielding Protestant granite. And on leaving the black room, we close the shiny lacquered door like a coffin lid and observe three symbols on the door. There’s a spade, which traditionally goes together with a coffin lid. There’s a blackberry. A medieval legend holds that this berry is black because the devil spat on it. And then there’s an apple blossom, like a rose. This is the flower of love, a reminder of the Mother whose love is ever-present throughout time and space. Be patient, but at the same time hurry towards shelter. /Translator into English: Filips Birzulis/ | |

| go back | |