|

|

| Aleksandra Beļcova and the French Riviera. Invitation to the Voyage Natālija Jevsejeva, Art Historian | |

| Luxe, calme et volupte – luxury, calm and pleasure. This citation from Charles Baudelaire’s poem ‘Invitation to the Voyage’(1) was used by Henri Matisse for the title of his work painted at St. Tropez in 1904. The idea of a Golden Age of Humanity, that somewhere there existed an idyllic place, a land of eternal happiness – Arcadia, has attracted both poets and artists since the time of Virgil. At the end of the 19th century Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir and Paul Signac were the first to find their Arcadia in the South of France, the country of their birth, on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. They were followed by the modernists of the early 20th century – Pablo Picasso, Fernand Leger, Haim Sutin, Andre Derain, Pierre Bonnard, Raoul Dufy and the already mentioned Henri Matisse. Among artists, a desire for escapism and the wish to flee from urbanized Paris was also given a further impetus by the First World War. As a result, at the beginning of the 1920s the French Riviera became home to many leading artists of the Parisian school. Although the Riviera didn’t become a metropolis of the arts and new trends didn’t arise there like they did in Paris, it was of major significance, both in the creative work of individual painters as well as in the history of art overall. Aleksandra Beļcova first went to Nice in late 1925. The wonderful natural beauty of the Côte d’Azur(2) fascinated her, and she created a whole string of sketches and drafts. But this first stay was brief – within a few weeks Beļcova was forced to leave France and hurry to Vienna, to the bedside of her husband, Romans Suta. A gastric ulcer attack had caused him to be hospitalized. His condition was very serious, and Beļcova was already receiving letters from her mother-in-law with instructions for a funeral ceremony. A number of months were spent in Vienna, in the hope that Suta’s health would improve, but the waiting was made more bearable by working on the art that she’d already begun in Nice.(3) It is significant that the wonderful Austrian metropolis left her indifferent, and in her art she returned to what she’d seen in the South of France. | |

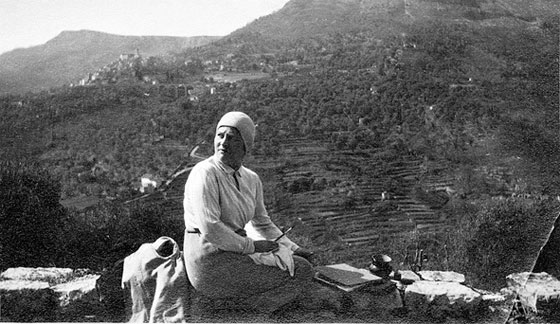

Aleksandra Beļcova in the South of France. 1930 Courtesy of Museum of Romans Suta and Aleksandra Beļcova | |

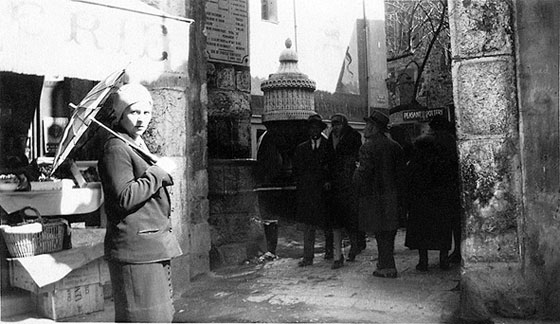

| The months spent in the cold, unheated little room she had rented in Vienna and her frostbitten hands made Aleksandra recall life in post-revolution Petrograd, and once again affected her fragile health. Her existing tuberculosis became worse. It was only due to the concern, care and material support of her closest friend, writer Austra Ozoliņa-Krauze, that Belcova was able to overcome the potentially fatal disease. The first time that the two women travelled to a clinic in the town of Vence, in the South of France, was at the end of 1927. Over the next four years the artist returned to the place every six months, and lived there during the winter and spring months. At times Beļcova was so ill that in Rīga she got onto the train virtually straight from her sickbed, and in Vence, at the start, for some weeks was forced to observe the strict regime recommended by her doctors: to sleep outside in the fresh air frequently and to go for short walks twice a day. Soon she’d taken in her close surrounds, and life in the quiet town became “fairly boring”. Drawing and painting became the artist’s main activities. The landscapes that could be seen from the terrace of her house or through the window of her room became one of the main themes in Beļcova’s works from this time. “The view from our villa is lovely – the old town, mountains and the sea, lower down the hill – a flowering orange grove,” she wrote from Vence in a letter to her sister. In nearly 85 years Vence has scarcely changed. The town, with its grey houses atop a gently sloping hill, is covered with something akin to the patina of time. The same old trees with sawn off branches continue to grow in a row alongside the city wall. Only now at the base of the hill there’s more greenery, and villas with tennis courts and swimming pools. The house in St. Jeannet Street, which was rented in Vence by the two friends, is no longer there, at least not under its old name – Villa Rey. Likewise information about the once famous local tuberculosis sanatorium has disappeared from maps, references and the memories of the local inhabitants. However, the French people, probably just as kindly as at the start of the century, responded to the rather strange requests from the author of this article to identify from old photographs the places against the background of which the artist from Latvia had once been photographed. | |

Aleksandra Beļcova. Vence. Oil on canvas. 60x80 cm. 1929-1930 Courtesy of Museum of Romans Suta and Aleksandra Beļcova | |

| Nowadays it is fairly easy to recognize the approximate place from which Beļcova painted her Vence landscapes – such a view towards the city opens up directly from St. Jeannet Street. Beļcova’s understanding of nature is distinguished by a particular emotional, lyrical perception. The elegiac moods in her paintings are brought in by the colouring based on delicate gradations of cool tones. The use of a soft palette of colour can be partly explained by the fact that the painter visited the South of France in winter and spring, when clear, sunny days are less frequent. This is not, however, the defining reason. The colouring of the Vence landscapes she painted is consciously stylized. The grey of the town houses and walls together with the greyish-green of the olive grove determines the overall tone. But the dark, saturated green of the evergreens (umbrella pines, palms and other vegetation) – a constant element in the natural scenery at any time of the year in the South of France – has been consciously ignored here. All of the dimensions and forms are subordinated to an airy ambience, a silvery, bluish haze. It dominates the whole landscape, and it seems that this haze is the main object depicted in the painting. Raoul Dufy, who lived on the French Riviera in the 1920s – 30s, believed that it was only here and nowhere else that one could see this special, all-encompassing and harmonizing bluish light.(4) Other French painters as well who have worked here have mentioned the singularity of the local natural environment. There’s a reason why Henri Matisse, in his time, was called “the priest of Mediterranean light”.(5) It seems that he wasn’t the only one to serve this cult... An interest in the portraiture genre had been apparent in Beļcova’s creative work since the beginning of the 1920s. In the South of France, too, where there was no shortage of “interesting landscapes”, she still preferred to make portraits of people. Beļcova’s friend Austra and the sanatorium dwellers posed for her and, of course, very often she did self-portraits. One of her most impressive works is Pašportrets ar Austras Ozoliņas-Krauzes ģīmetni fonā [‘Self-portrait with Austra Ozoliņa-Krauze’s Portrait in the Background’] (1927–1929, water colour and ink on paper, 41x60 cm, Romans Suta and Aleksandra Beļcova Museum (SBM) Collection). In it, Beļcova, following the style of the Japanese artist Tsuguharu Foujita, created a self-portrait with calligraphically fine lines and depicting on the wall behind her back a drawn portrait of her friend. Foujita used this compositional technique so that his portrait, like an illustrated story, would tell us about him, about his nationality and artistic signature, but for Beļcova the inclusion of her friend’s portrait was a sort of dedication, her h’ommage to a woman who had provided the artist with support during a most difficult period in her life. At the time when this self-portrait was done, the two women were virtually inseparable. The fact that the creation of this self-portrait was connected with the South of France is also indicated by a fragment of the hilly landscape with a view of the old town which can be seen in the open window behind the artist’s shoulder. | |

Aleksandra Beļcova. Anna. Pencil, watercolour on paper. 39,5x53,5 cm. 1928 Courtesy of Museum of Romans Suta and Aleksandra Beļcova | |

| The portrait Anna (1928, water colour and pencil on paper, 39.5x 53.5 cm, SBM Collection) painted by Beļcova, in which she portrayed a Vence tuberculosis sanatorium patient – an emigrant from Russia, was also created in the South of France. Anna, as opposed to Beļcova, lost her battle with the disease and died soon afterwards, right there in the South of France. Her husband, an aristocrat who’d also emigrated from Russia, continued to correspond with Aleksandra Beļcova after the death of his wife. The artist’s daughter Tatjana Suta related the story that during the Second World War, Ivan Nikiforovitch – as the man was called – came to Rīga to see Beļcova with a request for her to take over his property at Vence, a villa and a large fruit orchard with beehives. Beļcova, however, didn’t want to be separated from her daughter and declined the offer. Each time, whilst staying at Vence, when Beļcova’s health improved a little she took excursions along the coast of the Riviera together with Austra, “in order to gain inspiration for new works”. February in Europe is carnival time. The friends usually travelled to Nice and Menton to see the Battle of Flowers and the Lemon Festival. The dominating feature in the panorama of the beautiful, charming little town of Menton – the towers of the church of St. Michael Archangel – can be seen in a small study painted in oils (Menton, oil on cardboard, 35x26cm, SBM). But impressions from her travels materialised not only in the artist’s two-dimensional works. For example, participation in the Menton carnival inspired Beļcova in the creation of a decorative plate, Adieu vertu (1928, painting on porcelain, diam. 25 cm, Museum of Decorative Arts and Design Collection). On it, she has depicted carnival participants and musicians, all playing and singing from sheet music with the title Adieu vertu (the name of the Menton carnival official anthem, which translated from the French means “Goodbye virtue”). The little brochure with a clown on the cover – exactly like the one which is being held by the people depicted on the plate – was brought back to Latvia by the artist and kept (SBM). Another of Beļcova’s decorative plates Korida was also inspired by an excursion, when together with Austra she travelled to a small town on the French and Spanish border in the summer of 1928 to see the bullfighting. Every time they toured the Riviera, the friends dropped into Monaco to visit the Monte Carlo casino. Often their passion for gambling kept them there for many weeks. Aleksandra, as opposed to Austra, was not such a compulsive gambler and was able to control her habit. The artist also believed that gambling wasn’t dangerous for her because she didn’t have that much money. But it was alluring to tempt fate. Aleksandra perceived gambling as an opportunity of earning, and perhaps one day winning, a great deal of money. To a degree, that’s the way it turned out for her as well. For example, in 1926, the two friends twice travelled to Danzig with one goal – to play roulette. The first time, with the money she’d won Beļcova purchased and brought back to Riga pieces of porcelain to paint on, but the second time they both lost everything and could barely gather enough money together to return to Riga. On the 1930 visit to Montecarlo as well, Austra lost all her money but Beļcova, playing roulette each day for 2–3 hours, accrued a sum of about 2,000 francs after ten days. “As soon as I had 200–300 francs I went away, and in this way, over the ten days, I never came out at a loss. Therefore, if it’s possible to be satisfied with just a small win, you can earn enough to get by. I merely tried an experiment and it turned out,” she wrote in a letter to her sister. In the same letter, the artist justified herself saying that 200 francs was only a small sum, but to be fair it should be pointed out that at that time for 200 francs one could live at a hotel in Vence, with room service of fruit and wine, for seven days – as can be verified from her accounts which have been preserved. It could be that Aleksandra assessed her “achievements” so modestly because at other times her winnings may have been much greater... | |

Aleksandra Beļcova in Vence. 1928 Courtesy of Museum of Romans Suta and Aleksandra Beļcova | |

| In the spring of 1931, Beļcova travelled to the Riviera alone, without Ozoliņa-Krauze. At this time the friends began to drift apart and met increasingly less frequently. It should be noted, however, that Austra’s role in the artist’s life was providential. Thanks to her, Aleksandra was able travel in order to undergo treatment. At the Vence clinic a pulmonary resection was carried out on her – an experimental operation, which stopped the pathological progress of the disease. Within the artist’s family a legend was told about a high mountain with a cross on the summit that was located not far from the Vence sanatorium. There was a belief among the local residents and patients at the clinic that any patient whose name is scratched into – written on the cross, will definitely recover. The same legend told that Austra had done this for the benefit of Beļcova. The steep mountains around Vence at first make one doubt whether anyone but an experienced mountaineer with full equipment could climb to the summit. It should be remembered, however, that Beļcova lived to the age of 89 years and the doctors truly considered this to be a miracle, and found it hard to believe that such a powerful spirit could live for so long in such a frail and ill body. This year, 120 years will have passed since Aleksandra Beļcova was born. The museum named after her and her husband, Romans Suta, will mark the occasion with an exhibition dedicated to the artist called Aleksandra Beļcova and the French Riviera (15.03 – 2.09.2012), which will tell of one of the brightest periods in her life and in her creative work. It will be a chance to see the wonderful Côte d’Azur through the artist’s eyes and to encounter the world of “luxury, calm and pleasure”, which the French Riviera has been ever since the time of Henri Matisse, and still is. /Translator into English: Uldis Brūns/ 1 Baudelaire Ch. P. L’invitation au voyage. In: Fleurs de Mal. 1857. 2 The name of the French Mediterranean coast (in the French language). 3 From here and onwards biographical facts about Aleksandra Beļcova and citations are taken from the artist’s correspondence with her sister Marija Popova. All of the letters can be found at the SBM. 4 Костеневич А. Рауль Дюфи. Ленинград, 1977, c. 77. 5 Silver K. E. Chaos & Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany, 1918–1936. New York, 2010, p. 140. | |

| go back | |