|

|

| Still life and silent life Helēna Demakova, Art Critic | |

| On most days the Mūkusala Art Salon is a quiet place, not thronged with the crowds that gather at the unveiling of an exhibition by Kārlis Padegs or at any show by Maija Tabaka. In contrast, it is a space for viewing art at leisure and drawing conclusions about a particular phenomenon which some wish to define, describe or discuss. That phenomenon is Latvian art, of which the salon’s owners have an extensive collection. The non-commercial salon opened its doors in spring 2011 and mainly it shows theme-based selections from its collection. The exhibition of still life works held at the end of 2011 under the title Deceptive Silence was also representative of a part of the collection. An exhibition like this one cannot be compared to shows of selected works from a state museum. It is worth recalling the Latvian National Museum of Art 2004 exhibition Still Life. 20th–21st Centuries, in which the task of the museum experts was to display examples of various styles and works by different Latvian artists. Thus it was perfectly understandable that they included works such as a painting by Romans Suta influenced by Cubism, a work by Aija Zariņa using large fields of colour as well as Imants Lancmanis’ 1970s photorealist-style masterpiece. Although Deceptive Silence did not include works like these, we should definitely avoid the bad practices that have taken hold in recent art criticism, of writing about things that are not there, or could be, rather than what actually is – the conclusions that can be drawn from the existing rather than the desired. Deceptive Silence included 24 paintings by artists of all generations, starting with Johann Heinrich Baumann’s Still Life with Hunting Trophy from the 1820s. Like-minded friends and I found the exhibition very interesting, however, this was not due to the lines and colour mixes that several of the participating artists had been so enthusiastic about. No, it was a great show because in it the giant scissors of talent and thought that cut one artist off from another were suddenly revealed. | |

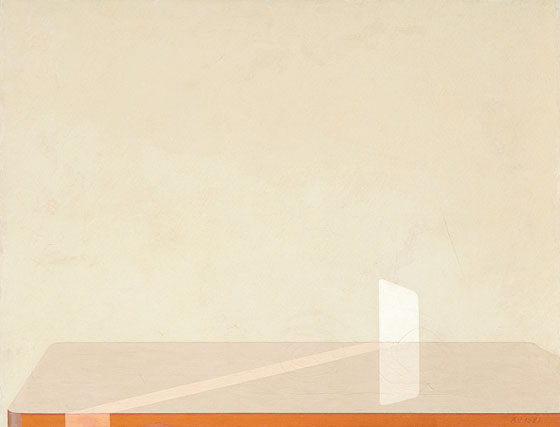

Bruno Vasiļjevskis. Still Life - Sunbeam. Oil on canvas. 50x65 cm. 1987 Courtesy of Mūkusalas mākslas salons Gallery | |

| The historic development of the still life genre could be seen in the exhibition simultaneously with contradictions in the contemporary interpretation of the genre. This gave weight to the observations of art historian Norman Bryson in his ‘Four Essays on Still Life Painting’: “Human presence is not only expelled physically: still life also expels the values which human presence imposes on the world. While history painting is constructed around a narrative, still life is the world minus its narratives or, better, the world minus its capacity for generating narrative interest.”(1) The exhibition revealed the stark contrast between a conceptual and a “virtuoso” ad hoc approach, which Bruno Vasiļevskis once derided as “made-to-be-ready-at-once”(2). “Made-to-be-ready-at-once” was the approach favoured by Art Academy teachers in the 1950s who stressed a broad, post-impressionistic (but primarily earth-toned) painterly gesture. For example, the artist Breikšs used to reiterate to his students: “Paint so that foam froths out of both ends.”(3) However, froth is just froth, and it would be futile to think that everything that is collected is of the highest quality. This froth was conceptually opposed by those once-young artists who in the 1960s made up the informal “French group,” and two paintings by a member of this group, the intellectually influential Vasiļevskis, form the core of excellence of this exhibition. The contemporary interpretation has attracted a wide range of works whose claims to belonging to the still life genre are dubious. Apparently some experts believe that contemporary still life includes pop art (such as Kristaps Ģelzis’ 1998 installation Ņam Jums Paika, a mixture of objects and video owned by the Latvian National Museum), photographs or some ironically postmodern, alienated object. Still life may also cover a painting of rubbish in a forest (Auseklis Baušķenieks’ Still Life in Nature, 1973) or just a simply-depicted pile of rubbish (Frančeska Kirke’s Global Still Life, 2011), in which the stillness is supplemented by a dog in the right corner and a skull on the left. The aforementioned are open structures, compositions that may be supplemented if desired; we will return a little later to the notion of still life as a “closed structure” and a world view with a limited arena of passion. Both a contemporary (here used as a synonym for the word “slapdash”) interpretation of still life as well as the attitude many artists have towards the genre makes it possible to formulate the difference between mere decorativism and art in which the artists has aimed for and realised an intellectual goal. I will try to provide some examples. For the first few decades of my life, I lived in the same room as Leo Svemps’ 1954 still life with a vase, flowers and apples and Romans Suta’s 1928 Cubist -style painting under glass with a phonograph record as part of the composition. Looking at these works, already from an early age I began to ask myself the question “why”. Not when, what or how, but why. The issue of Svemps (and the exhibition included a similar work by Svemps, his Still Life with Open Book from circa 1936), became clear to me in my teenage years. Svemps was a “virtuoso”, whose beautifully provincial, self-sufficient art was an affirmation of the relationship among colours and expressiveness. For some, artist or viewer, this may be enough. But others may not be satisfied, and thus begins a quest for truth and discoveries that in still lifes sparkle like genuine precious stones. I understood Romans Suta much later, at the age of 20, while sitting, smoking and crying on the black stairs of the Art Academy. If I can’t even draw the model’s head properly, how will I ever become a real artist?! Then it dawned on me that great art is different to the uniform “assignments” of the academy’s preparation classes, which were parodies of still lifes. While thinking about Suta, the word “task” crystallized in my mind. When gazing upon the paintings of Leonīds Āriņš, Raimonds Staprāns, Bruno Vasiļevskis, Uga Skulme and Boriss Bērziņš in Deceptive Silence it crystallized further. Although the works of Suta and perhaps one or two other major artists included in the National Museum of Art still life exhibition could be accused of emulating Western styles, this is not a negative criticism. (After all, this is a Latvian salon, not the 19th century French academic salon and in principle it does not discuss style; it is the flexible absence of any specific style.) Variations in style have been a fact of life since the golden era of art, that is late 16th century Florentine art, in which every great master was unique and inimitable even though working from common stylistic foundations. In the context of style, a set task is a self-explanatory matter. I have never understood the concept of mindless stylization or something being “style-free” as justifying creative activity, although good interior decoration also serves important, mood-enhancing functions. I could dwell on history that goes further back than the interplay between Suta and Svemps in my former communal apartment room. However, in my opinion, it would probably be wrong to see the origins of the still life genre in antiquity. The paintings found in ancient Egyptian tombs revealing pre-Christian beliefs and the instructions from priests about meals to be enjoyed in the afterlife cannot seriously be considered to be the precursors of still life. Nor can the antique testimonies of mimesis in the paintings and mosaics of flowers, fruit and household items found in Pompeii which have remained so brightly and colourfully preserved under Vesuvius’ ashes until the present day be considered examples of the genre. All of the previous statements are serious self-irony and a reminder that genres can only be understood through careful scholarship, nurtured in silence, and not from ceaseless wanderings around the world. | |

Caravaggio. Basket of Fruit. Oil on canvas. 46x64,5 cm | |

| In antiquity there was the word XENIA which was used to describe dishes presented to guests that had been painted by artists of the time. These stories are not significant in the development of still life as a genre, and my personal reaction upon first hearing the word XENIA does not relate to the origins of still life. Rather, it makes me recall the dialogues published under that name, compiled in 2007 by Dimitry Timofeyev and initiated by Oleg Kulyik, in connection with Russia’s greatest ever exhibition Верю (‘I Believe’). In these collected pre-exhibition conversations, the guests received gifts of the spirit instead of the paintings of food from classical antiquity. When discussing faith, Kulyik takes the words out of the mouths of Cezanne, Vasiļevskis and even (hypothetically) Vermeer: “I consider religion to be the ecstasy in the face of reality, the experience you believe in…”(4) The paintings of the Renaissance masters in which the figural composition is supplemented by compactly painted groups of objects in the fore or background are not examples of still life. The proto-Renaissance frescoes with liturgical subjects by Taddeo Gaddi in Florence’s Santa Croce Basilica (circa 1337–1338) are also just a wall decoration, although the motifs do have a symbolic dimension. Therefore the main characteristics of autonomous still lifes are not the allegories depicted in them, just as the fact that da Vinci’s Mona Lisa has some countryside in the background does not make it a landscape painting. Caravaggio’s sensitive, feminine boys with bunches of grapes, peaches, pears and flowers are not just a portrait plus a still life on a single square of canvas. Here I will take the liberty of disagreeing with art historian Ernst Gombrich’s opinion that Vermeer’s works are “essentially still life with human figures”(5). Nor do I share the views of the great art historian H.W. Janson, who wrote that Vermeer’s works “exist in a timeless “still life” world, seemingly calmed by some magic spell”(6). Such an assumption excludes Vermeer’s women, who as Julian Bell points out “have minds of their own”(7). Vermeer’s works are outstanding examples of figurative painting. There may be an understandable urge to discuss the all-embracing “still life” in Vermeer’s art for certain philosophical reasons, for example, because “his formal idealisation of natural objects reflects his attempt to describe the infinite by finite means”(8). Nevertheless, the storytelling in his paintings, although muted, subtly teases out the human presence in daily chores (pouring milk and making lace), pastimes (a music lesson) and mischief (sending a secret letter). Conversely Caravaggio’s Fruit Basket (1598–1599, possibly 1601) is a still life, and was one of the first examples of the still life genre in Europe. This work painted in trompe-l’oeil style does not become a still life because it “can be seen more as a melancholy existential meditation on nature than as a proud affirmation of her positive qualities”(9). Rather, it is still life because in form and content, colour and composition, it is complete, perfect and self-contained. It is the vision of an ideal world using artistic techniques: “thus the objects of a still life, although they appear accessible, are actually inaccessible, fictional. Created: ideal as opposed to real. They and their interpretation and articulation embody ideological conventions and patterns. Removed from the direct experience of the real world.”(10) In the centuries that followed, the greatest paradox arising from the still life genre was the inexplicable but prevalent tension between the ideal and the real. Artists look at nature and try to express its nuances, vibrations and structures, yet in reality they are seeking and occasionally find the real points of colour in a space subordinate to the ideal composition on the canvas. Still life is a field of painting, as we were able to learn at the Mūkusala Art Salon. After Caravaggio’s Basket of Fruit, autonomous still life blossomed in Dutch refinement, Spanish mysticism (Zurbaran) and French elegance from the 17th century even up to 20th century masters like Cezanne, Picasso, Matisse and Morandi and other modernists who heralded and developed the avant-garde via the “conservative” nature morte genre. According to Ernst Gombrich, from the 17th century onwards the triumph of Dutch still life, “to their own surprise, these masters were made to understand that the depicted object is actually less important than might be imagined”(11). Let us recall that while the Dutch openly demonstrated the mastery they had learned, at the dawn of modernism Cezanne rejected the accuracy of the drawing in order to create balanced truth for the painting itself in the spirit of Poussin and other classic French masters, which arose from intensive observation of nature.(12) Deceptive Silence is a deceptive title for an exhibition, just like the name of the exhibition Not so still life which was held in California at the start of the third millenium and which had oranges painted by Raimonds Staprāns on the cover of its catalogue. Still life is silent, and even dead in a sense – hence the French designation nature morte. Still life is created in the quiet of the studio, away from the hustle and bustle of everyday life, crystallized out of the “natural”, living world. It is a completed world rather than a fragment to be cut and pasted into some landscape together with other figures. It is an artificial yet humanly constructed harmonious whole, which over the centuries has consecutively spoken about symbols, colour in space and of the sort of visuality wherein it is possible to capture objects and suspend temporally moving events on the surface of the canvas. | |

Raimonds Staprāns. Still life with falling mist. Oil on canvas. 112x112 cm. 2004 Courtesy of Mūkusalas mākslas salons Gallery | |

| More than landscapes or portraits, still life is the universe in face of chaos, it is an aesthetically ordered environment in which a great master avoids chance happenings. A great master finds a specific colour for each point in space; as Eduards Kļaviņš wrote about Bruno Vasiļevskis, he was “able to realise the search for ideal plastic forms”(13). This quote could equally be applied to the works of a number of other artists in the Mūkusala Art Salon exhibition as well. Staprāns, Āriņš and Uga Skulme have followed the complex path of abstraction, separating the ordered world from the non-mandatory surroundings beyond the edge of the table. The eye only perceives order, although this order may be full of drama, as Cezanne in the past and Staprāns today demonstrate. I once wrote that Staprāns’ paintings have triumphed over life in its illusory, trivial, neurotic abundance.(14) All good, serious still lifes suspend life and condense its ideal facet which is, nonetheless, whether we like it or not, connected to its opposing imperfection, verbosity and deception. /Translator into English: Filips Birzulis/ 1 Bryson, Norman. Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting. London: Reaktion Books, 1995, p. 60 2 From a conversation with Imants Lancmanis on 7 December, 2011, in Florence. 3 From a conversation with Imants Lancmanis on 19 January, 2010, in Riga. 4 XENIA или последовательный процесс. Сост. Д. А. Тимофеев. Mосква: ММCI, 2007, с. 19. 5 Gombrich, E.H. The Story of Art, p.430 6 Janson, H.W. History of Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986, p. 534 7 Bell, Julian. The Mysterious Women of Vermeer. The New York Review of Books, December 22, 2011 – January 11, 2012, p. 87. 8 Huerta, Robert D. Vermeer and Plato: Painting the Ideal. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2005, p. 11 9 Bonsanti, Giorgio. Carravagio. Florence: Scale, 1991, p.8 10 Rowell, Margit. Objects of Desire: The Modern Still Life. New York: The Museum of Modern Art and Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997, p.10 11 Gombrich, E.H. The Story of Art, p. 430 12 Ibid, p. 543 13 Klaviņš, Eduards. Bruno Vasiļevska ideālā realitāte. No: Bruno Vasiļevskis. Rīga: Neputns, 2005, 14. lpp 14 Demakova, Helēna. Meksikas tuvums, putna lidojums, paralēlās dzīves. No: Raimonds Staprāns: Glezniecība. Rīga: Nacionālais mākslas muzejs; Neputns, 2006, 14. lpp. | |

| go back | |