|

|

| TIME WILL SHOW Norbert Weber | |

Maija Kurševa. 2008 | |

|

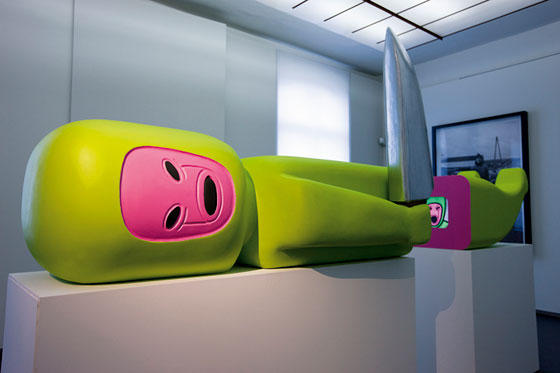

On 24 February the exhibition "Time Will Show - Contemporary Art from Latvia" opened at the Museumsberg Flensburg. One of the two museum buildings houses the major culturally and historically significant furniture and church paraphernalia collection of the entire Germany and Denmark border region, spanning the time period from the Middle Ages to modern times. For some 15 years all works of art have been held separately, in the next-door building. It houses the Art Museum, which has hosted some important exhibition projects over the past few years, for instance, in 2007 it held the first exhibition devoted solely to portraits by Gerhard Richter - an exclusive display presented only in Flensburg. In the first of the five rooms devoted to the temporary exhibitions, on the wall to the right of the entrance, hung Richter's "Herr Heyde" - a work that has now been added to the museum's collection. It is a portrait of a doctor who had close ties with the Nazi euthanasia programme and went into hiding after WWII under the assumed name of Heyde. The doctor is shown at the moment of his arrest in 1959 (in Flensburg). Gerhard Richter painted this portrait from a photograph published in the newspapers - a method he often used at the time. He softened the stark realism of the original by smudging the picture and creating a blurred effect. This painting is the central piece in a series of works from the 1960s, in which Richter polemised on the subject of the Nazi past. At the next exhibition, "Guaranteed: Art", the same spot, just opposite an installation by Raffael Rheinsberg, was allocated to Sigmar Polke's painting "Erich". This 1969 work quotes information published in a newspaper, which stated that Margot Honecker keeps the ashes of her late husband Erich Honecker, former leader of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or SED), at her home, as the deceased's wish of being buried at a socialist memorial in Berlin remained unfulfilled. "On the other side of sensationalism, the artist turns a newspaper article into a visual image. He melts what was published in the press into an all-unifying raster and places the urn on a shelf in a petit-bourgeois living room. Shades of purple blend into shades of grey, and the spectator may get the impression that ashes may have been used in the creation of this painting. The importance of the once most powerful man of East Germany has died away, turning into a blurred depiction of history."1 It was with these paintings in mind that I visited Riga in late January. Upon arrival I was greeted with numerous enthusiastic references to an exhibition that was held at the Arsenāls Exhibition Hall. The exhibition was titled "Candy Bomber/Našķu bumba" - a seductive, apetite-whetting label. During my visit of the exhibition my companion asked me to explain to her the criteria I use to evaluate works of art. Thus I couldn't view the exhibition in my usual way, walking through it in consecutive order and using many years' worth of visual experience; instead, I had to stay focused and provide commentary on each painting or each group of works. This is not the moment to repeat the things I told my companion, because I think it may be more important to recount my personal impression, formed alongside the commentary provided during my visit. My mind was on the exhibition "Time Will Show - Contemporary Art from Latvia", which was during these days being prepared for the Flensburg Museum by Ojārs Pētersons, and the wall on which Gerhard Richter's and, for a while, Sigmar Polke's paintings used to hang. It was a game I played in my mind, looking in turn at each of the works presented at the "Candy Bomber" exhibition, and imagining them hanging on the aforementioned wall in Flensburg. I would gladly have given Ojārs Pētersons some suggestions, but the result was unfortunately less than satisfactory. I didn't find a single painting that seemed suitable - even if I would apply all the indulgences that young artists are entitled to. When I reflect on this now, next to the "sweet" title there are two remarks about this exhibition which make me think: "The exhibition serves to popularise this genre of art [..]." Here I have to wonder which genre could be more popular than painting. It goes on: "The overall task is to promote the further development of the local art market."2 These are rather odd statements that underpin the "Candy Bomber" exhibition. Perhaps this is the reason why I did not find any serious offers for "my" wall. Meanwhile in Flensburg, the exhibition "Time Will Show" had already opened and it was revealed which work had taken the spot on the "ominous" Richter and Polke wall. It was a black-and-white large-scale photograph of a man who was literally hanging mid-air against the backdrop of a farmyard - a barn, a tractor and an electricity pole. What "miracle" was this? The obvious guess - that this man had achieved this position by means of digital processing of the image - is not correct. I insist that this can be felt, even seen. The figure does not look at all cut out. So it must mean that it really was hanging in the air at the moment when the shutter button was pressed. But the sensory effect of the image does not come from the documentary manner of its creation. It stems from the fact that Kaspars Podnieks, who staged this situation himself, has managed to describe a state which today is of great ambivalence to him and also to many other people - namely, the idea of being separated from one's traditional background, of flying without knowing whether to feel bliss or to fear the possible fall. The image created by Podnieks is so serious that it (like Gerhard Richter's paintings) needs no colour, and it never loses its credibility, even when its construction - as illustrated in the catalogue - is documented in full colour. By the way, the same is true of Richter's and Polke's works, which lose none of their artistic value if placed next to the newspaper cuttings they are based on. The room in which Kaspars Podnieks's photograph was exhibited held three more works. In the middle of the room stood Maija Kurševa's object "Bēdu ieleja" (Valley of Tears) - a figure cut in two and propped up on two plinths. As you pass between these two parts, an eerie experience is created. The juncture holds monitors from which snarling dogs are barking at the passer-through. Like old fairy tales, this modern, comic-like tale possesses a dose of cruelty which, in addition to the horror, provokes something resembling catharsis. The opposite wall held Anete Melece's "Piecas animētas gleznas" (Five Animated Paintings), which are combined into a single interactive work of art. Collages, created using computer animation, tell of dying flowers, a bored nude model, her husband Viktors and tourists against the backdrop of a picturesque mountain landscape. At the same time the spectator experiences a memorable trip through the history of painting: the curtain, a quote from Mark Rothko, parts and reveals a trivial landscape, the good old still life comes alive as water from a watering-can pours on the dying flowers, Goya's naked maja (alias Larisa) is moved from museum-like alienation to an IKEA sofa, and the setting sun from the kitschy mountains brings movement to the rigidity of the classically modern composition. The intelligence, love and ironic view of painting in this five-part work say so much that it is nigh on impossible to stop looking at it. The fourth work exhibited in this room was Krišs Salmanis's computer animation, "Duša" (Shower). Here one of the walls has been transformed to make one of its corners extend into the space between ceiling and floor. In this wall construction there is a 30-centimetre deep rectangular window, set at eye level. Behind it there is a monitor which shows a shower, in which a black man is himself dissolving under the streaming water, as if completely disappearing from our (voyeuristic) view. This first room of "Time Will Show" immediately revealed the special qualities of the exhibition. Even though almost all of the artists represented in it have studied at the Visual Communications Department of the Latvian Academy of Art, this exhibition was not about the so-called new media. Here there was a combination of different art genres: sculpture, painting, video, graphic arts, animation film, photography, audial art, installations; anything goes as long as it serves to define the expression more precisely. The work and care put into preparing the prerequisites of the presentation must also be commended, down to the constructive reorganisation of the space. Speaking of prerequisites, it must also be said that even those works that needed a computer monitor were exhibited in aesthetically faultless constructions, ones that hid everything that could interfere with the work and disturb its spectator - technology, consumer design, company logos etc. When the conclusion has been made that discarding the plinth and the frame has long since stopped being an avant-garde act of heroism, but is instead indicative of sloppiness, efforts to find the best possible way of presenting art come with considerable difficulties. This was worth seeing at the "Time Will Show" exhibition. Here it occurs to me that I saw Andris Eglītis's paintings twice on the same day - once as a part of a lovelessly assembled line of portraits at the "Candy Bomber" exhibition at Arsenāls, and later within a series of urban landscapes at Andrejsala. These paintings were surrounded by large wall constructions, clad in grey canvas, which functioned as "frames": a precise and impressive piece of staging. The second room of the exhibition was dominated by Martins Vizbulis's "Power" - an installation which is a combination of a time machine, a power station, a source of heat and light. The effect of this creation is so strong that I would have wished for it to be exhibited in a separate room, all by itself. The two other works in this room needed a highly focused spectator to appropriately appreciate their quality. I am talking of Dace Džeriņa's video "Laimīgā zeme" (The Land of Happiness), which is such a powerful testimony of the poesy of everyday things and events that, to me, even the simple process of dusting seemed to amount to a sacral act. The video "Es neskatos" (I Am Not Looking) by the artist group F5, probably my favourite among the works of this exhibition, was displayed near the exit of the room. It shows a situation as if in passing - a line of chairs in the waiting-room, a woman sitting in the rightmost chair. This room leads to the next - the third room of the exhibition. Right by the entry, in the very same spot by the door, the video is displayed. Except here the woman's face is in close-up. The woman is crying. There's no sound, just a crying face. But this work is not about a crying woman. It is about us. We cannot do both things at once. We have to choose - to observe or to get involved. Or maybe this necessity of taking a stance is too much? In that case, Anta Pence and Dita Pence are offering us an attractive alternative in this very room - a film titled "Stīvenam pa pēdām" (Uphill to Mexico), created in 2001, which I had already seen but, as with any good movie, am happy to watch again. And the best thing of all: a look behind the scenes! Pure mechanics and genuine joy. We're always so happy to feel like kids! Our visit to the exhibition continues with the fourth room, which houses an interactive video installation by Ģirts Korps, "T" (sound by Nils Austrums) - a work previously unseen by the German public, but known in Latvia since the exhibition "Jukas" (Disorder), which was held at the Arsenāls Hall in April 2005. This exceptional work on the subject of fear still hasn't, in my opinion, met its best method of display. Here I would still like to see some other solution, perhaps one which would not need a joystick, and where the pictures supplied by four cameras would be controlled simply by the movements of the spectator or - better yet - with the aid of a bioport implant. Katrīna Neiburga's video "Vientulība" (Solitude) is yet another case of what I have already written about Dace Džeriņa's work. For this wonderful triptych to function, the spectator has to become in tune with the work; that is, to put on the earphones, devote some time to it, focus and accept the intimacy that is created by remaining one on one with pictures that tell you what it is like to be alone. It is undeniably difficult to be right next to Evelīna Deičmane's combined video and sound installation, "Nesapņo un nedomā" (Don't Dream, Don't Think of It). Here I will interrupt my reflections on this exhibition and turn to the catalogue that accompanies it, because I cannot describe this work better than the artist herself: "On a plinth under a glass cover stands a turntable which is playing a vinyl record. It has been assembled from two completely different records which have been cut in half beforehand. During play-back, songs from two different eras are heard. New sound is produced. Next to the turntable a video of my grandmother is played. Her facial expression changes, and these changes reflect different periods of life and memories [..]."3 The book about this exhibition merits a separate mention, as it possesses qualities not necessarily associated with every catalogue. First of all, it discards the patronising cliché of substantiating the exhibited works with a theory which could only hinder their perception. Instead, Jānis Taurens offers the reader a very entertaining fictitious dialogue between Barbara Rose and Sol LeWitt on the subject of contemporary Latvian art. The fact that each of the artists get to have their own say provides the book with the necessary authenticity. Finally, the end product is made complete by the carefully crafted and exceedingly beautiful design, created by Ingrīda Zābere. After this digression we return to the fourth room, in the middle of which, among the aforementioned works by Ģirts Korps, Katrīna Neiburga and Evelīna Deičmane, stands an object worth mentioning - worth mentioning because it is a true sculpture, like a classic piece of fine sculpting. It is an object that speaks for itself; an undulating shape crafted from solid metal, yellow, shiny and "pretty from all sides", so to speak. Had Armands Zelčs painted this creation, or shot a video of it, it would at best function as a metaphor. As a spatial object at 1:1 scale it is more than just an inspiration, it is a provocation right in front of the spectator. These steps, which become narrower towards the top, could really be climbed. And then, as you slide down, there would be no escape. The torture would start afresh. This "Sisyphean feeling" cannot be achieved with a picture - it comes solely through the sense of identification which such an object can create. The final room of the exhibition "Time Will Show" held works by Kristīne Kursiša and Miks Mitrēvics. This was a room which reflected the title of the exhibition particularly well, thanks to the perspective it offered. Among Kristīne Kursiša's works were two classic paintings on canvas - a portrait and a landscape. The artist has given these usually static images a dimension of movement, created by video projections onto the surfaces of the paintings. I especially liked the projection on the landscape which showed the Gūtmanis Cave. It shows how ancient myths are trivialised yet can still in certain circumstances keep their wonder (in painting, childhood memories). I know now that I am going to visit this place. And then there's "Ģimenes portrets" (Family Portrait), a work which holds a secret. On the wall there are two reliefs of horses' heads: one shows a single head, the other - a pair. What family is this? And why there is something blood red oozing from under two of the heads? As the head is pushed aside, a little window is revealed. It shows a scene created with toy figurines, a skittish horse surrounded by a pack of wolves. The story has been told, but the intrigue is preserved. At the end of the exposition I stumbled on Miks Mitrēvics's works which I had already seen the previous year in a stack of two containers by the Andrejsala pier. Keepsake photos that move in ventilator-created wind, little scenes put together from simple materials, a video that shows a road up a hill, a chaotic assembly of big and small events that the artist has met with, ones that each spectator meets with - in one way or another. That's exactly the feeling I had as I walked through this special room at the end of the exhibition and examined its inventory: fleeting memories, the past, disappearing from rear view. Lost in thought, I watched a little scene - a figure in a hammock. Then I noticed that here, as in Andrejsala, Miks Mitrēvics has come up with a special offer - namely, a look beyond the world of memories. In Andrejsala some steps led to a platform from which you could let your gaze roam. Here, in Flensburg, for the first time I had the opportunity to look through windows that had usually been curtained in white, and enjoy the view of a garden at the foot of a hill. A little corner of paradise. Here the gaze was drawn ahead. Here the phrase "Time Will Show" acquired the optimistic meaning I would most like to attribute to it. This may be the right moment to announce that the German critics greeted this exhibition with rave reviews. And, if we look further than that, we may also reveal that two of the artists who put their unique stamp on the exhibition - Evelīna Deičmane and Miks Mitrēvics - have been invited to "Manifesta", the contemporary art biennial of greatest international importance. I am sure they will also have a good run there. Time will show. Norbert Weber is a professor of art collection management at the Institute for Art History of Christian Albrecht University in Kiel, Germany. 1 Graulich, Gerhard. Sigmar Polke. Erich. Mit Sicherheit: Kunst. Flensburg: 2007, p. 22. 2 Candy Bomber. The Young in Latvian Painting. See www.lnmm.lv 3 Deičmane, Evelīna. Nesapņo un nedomā par to. Laiks rādīs. Eckernfˆrde: 2008, p. 46. | |

| go back | |