|

|

| Working The Fields of Art Martins Vizbulis Conversation with Modris Sapuns | |

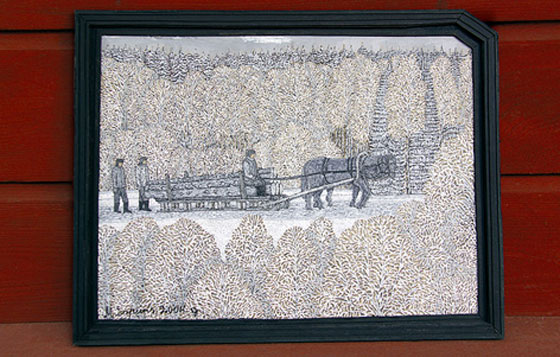

Modris Sapuns. Guardian angel. 2007. | |

I arranged to meet Modris on a Sunday, to be able to visit the Ģipka Lutheran Church (in the Talsi district) and see Modris's latest creation - painted panels for the church altar table. Modris had planned to attend the service in Talsi but decided to change his plans for our meeting. Following Modris's directions, I drove to his house, Krovalki, in Laidze rural district. As I saw the house in which Modris lives I realized where he draws the strength and inspiration for his finely crafted works of art. Tidy surroundings, a beautiful home. You could most definitely film a TV series about vintage rural life here. Soon they will have to leave this place, as it has another owner and Modris's family has already bought a house in Laidze. They say it is beautiful there as well. On our way to Ģipka we are sitting in the car and talking. Martins Vizbulis: How did you start drawing? Modris Sapuns: Drawing came to me when I was very young. I've been living in the country since I came into the world, I grew up in this house. We used to have animals - pigs, cats. We've always had cats. For a time we had dogs, too. So, living this life, I started to put some things down on paper quite early on. M.V.: Like all children do. M.S.: Exactly. I picked up a pen and doodled on sheets of squared paper. Cars, tractors that were always around in the country. I remember that one time I saw tractors and sowing machines in the collective farm fields which used to surround our house; I took my toy car to those fields and messed about among them. And that's how I started drawing cars, animals and people. When I was at school I also had ideas for all kinds of drawings - of forest work like chopping or sawing wood. My uncle [artist Andris Vītols - M.V.] also looked at what I was doing, and he liked it; he decided I had a talent for drawing. That was when I was at school. He also has a studio, similar to what I have now. Back when I was at school I used to go to his place to draw. My first solo exhibition was at the Mazirbe School when I was in 8th grade. My Indian ink drawings were exhibited in the school corridor. Artist Guna Millersone told me a story about Modris. He was different already at school - for a drawing assignment on the subject of family Modris depicted his family as a herd of deer, with his father, mum, grandmother and seven deer calves (himself and his siblings) M.S.: After I graduated, Andris [Vītols - M.V.] arranged for lessons with printmaker Ritma Lagzdiņa, who had a school in Talsi, and she tutored me for a year and a half. Andris arranged it with her that I shouldn't be influenced and taught too much, so that I wouldn't lose what I had naturally and start imitating others. Some composition, some landscapes, just to kind of guide me. So I would get noticed more. In the summer of 1998 there was an exhibition in honour of the city of Talsi, The Pride of Talsi, in which I was put with other artists for the first time. Neither my parents nor any of my neighbours had expected me to become an artist. I hadn't expected it myself. At this exhibition Modris presented a plywood carving of his favourite Mazirbe teachers - Maija Valce and Pauls Valcis. The exhibition was followed by an invitation to take part in the project Ventspils. Transit. Terminal. M.S.: Time goes on and I keep going too, just working away in the fields of art. In the late 1990s I did some woodcarving work for Andris Vītols, who has a carpenter's shop. I've chiselled some seats. And from 2003 to 2006 I was right here at the carpentry school in Valdemārpils. M.V.: Isn't that with Igurds Baņķis? M.S.: It is! That's where I learnt woodcarving. M.V.: He trains apprentices. M.S.: Yes, yes! I also became an apprentice. In my third year or so. I made a little altar with the entire altar-piece carved in wood. It has a figure of Jesus and people coming to him. A cross carved in wood, some angels. M.V.: Where is that little altar now? M.S.: At the school, with Igurds. Do you know where that is? M.V.: I do know, I also studied with him. We can go there on the way. We drop in at Igurds's home without notice. He speaks of Modris's work, praising his enviable patience, artistic talent and individuality of technique. Because of the limitations on the depth of cut, Modris supplemented the plywood carving with some shading in pencil. Igurds shows us pictures of Modris's graduation work (it features a tiny angel, carved in three dimensions rather than the relief technique of the rest of the altar) and says Modris should start working in this manner, switching from flat planes to spatial work. The little angel was actually the result of a mishap, but Igurds thought it so good that it was given a place on the altar shelf. We drive to the workshop which now houses the altar. After a short tour of the shop we arrive at the altar itself. The little angel has now lost both its wings. Igurds says that up until recently, just one wing had been missing, and adds that people like destroying beautiful things. It makes them feel better. Apparently, someone had seen the altar as competition and envied its beauty. Similar incident has also happened at the sculpting shop, where the pupils destroyed the best clay model so that there would not be anything to which their own work could be compared and it would as a result seem better. Then Igurds shows us a room which is going to be redecorated to become a lounge for the apprentices. A space there is reserved for the little altar, just to have something that would comfort anyone who might feel lonely. M.S.: A couple of years ago I took part in a naïvist exhibition. M.V.: Which one? M.S.: It was called The Naïve Kurzeme. Many of the artists are older people, many are already deceased. I'm the baby of the naïvists. [Modris is not yet thirty - M.V.] | |

Modris Sapuns | |

|

When I met Modris at his home, I noticed an unfinished piece on the table in his studio, and found out it had been commissioned. M.V.: What subjects are most in demand for commission work? M.S.: One well-known group of people wanted their country house and its surroundings. Then I've had commissions for some scenes from the Bible, with baby Jesus in a manger, his parents beside him and the shepherds coming to see him. And then some angels playing various musical instruments in heaven. Right now I am doing a commissioned piece with some people and an angel standing in the background, watching over them. M.V.: Do you do many religious pieces? M.S.: Yes. Just now a girl commissioned me to make four little Christian-themed scenes, with Jesus as a shepherd. She wants one for herself, and also ones to give to her friends and parents. And then there's a commission from the Ģipka church. M.V.: That's a serious one. M.S.: Yes, it isn't going all that easy. It is fiddly work, but it is worth doing. M.V.: Why is it more fiddly? Because of the larger size? M.S.: That's right! All those sketches, and the time it takes to do everything. You have to get the shading right, so that all pieces are more or less similar. M.V.: A bit of a responsibility. M.S.: Yes! You have to take some care with it. M.V.: It is also a bit daring. As I understand it, all of the work was commissioned by Dr Valdis Randa. M.S.: Yes, he's the parish elder. M.V.: That's some responsibility he is assuming - most churchgoing people are used to classic painting, something realistic. Your works are more akin to the graphic arts, not painting. M.S.: It depends. Mostly I create my works out of dots, but I did not use this technique for the church. I kept it simpler there, with various shades of grey. This idea actually belongs to Andris Vītols. His workmen are renovating the church, making altar tables, the pulpit. Andris had mentioned in the parish that it could turn out to be covered in pictures, he was wary at first, thought it might be distracting for people. That people might look at the pictures all the time and not hear what the minister was saying from the pulpit. M.V.: You mean they're worried about you - that you would take away people's concentration with your works? That people might find them more interesting than the sermon? M.S.: Yes, that's it. But later, when they discussed it, it turned out the main reason was money - they were afraid they wouldn't be able to pay for it. So they tried to find an excuse at first. But this idea was still needling Andris, and in the end it all worked out. People realized that it was worth it. Randa is also happy. M.V.: From what Andris was saying I gathered that you'd continue your work there. M.S.: Yes, now it's the turn of the pulpit. And then there's also an idea for the front of the altar. M.V.: Do you submit your own ideas in sketches, or do you work with the minister and the parish elder to decide what should be depicted? M.S.: I make some sketches and then Vītols and I decide what should go where. The church trusts us in this respect. M.V.: Are you a churchgoer yourself? You wanted to go today as well. M.S.: Yes, I attend the Talsi Lutheran Church regularly. In Ģipka we find the church with some difficulty (the town is sparsely populated and the church is quite a ways from the centre). The church interior is a work in progress, but I can tell it is going to be understated and, in my opinion, very tasteful. I don't know much about religion and religious people's perception of beauty, but before my MFA studies at the Latvian Academy of Art I graduated from the Woodcarving Department of what is now the Riga Design and Art School - and I can say that I found the interior in keeping with the building, and that Modris's images were a good fit. The work is still continuing. The altar panels will house scenes from Ģipka history. I hope Modris will be entrusted with the altar-piece as well - the church would then be sure to achieve a uniformity of style. | |

Modris Sapuns. 2004 | |

|

Leaving Ģipka, we drive to Modris's place. He promises to show me his works. The studio atmosphere is reminiscent of a memorial home of some famous artist (everything tidy and senile, like a museum). It is located on the first floor, from which there is a picturesque view of the country landscape. M.V.: Do you go fishing? M.S.: I don't have the time. I do watch some television. Read a book sometimes. M.V.: What kind of books do you read? M.S.: The Bible. Some other Christian books. M.V.: What else do you do? M.S.: I've carved spoons at home with little chisels, and made some small crosses. And then there's my hobby, of course - I like picking berries in the woods. In the summer I go to the forest. And also to the seaside. I like the sea, we go to Upesgrīva, that's closest to us. When we had livestock I took care of the animals. We had some cows and pigs. Some fowl as well - chickens and geese. The animals took half a day to take care of. The same goes for gardening work, and the autumn harvest. M.V.: Do you mostly work and draw at home? M.S.: That's the way it usually works out. Outside, if there's firewood to be chopped or stacked under a roof, I go and do those things as well. I tidy up the front of the house, bring in the firewood, make the fire. That's how I rest my eyes. It is hard to sit and draw all the time, sometimes you also need to rest. M.V.: Have you drawn ships as well? [We are at that moment crossing the Roja bridge, from which the harbour can be seen.] M.S.: Yes, yes, I have! Where the Venstpils pier is, there are some boats there! I have that picture at home. M.V.: And you've done portraits? M.S.: Yes, but not from nature - I do them from photographs. At home I have several portraits of the older artists. M.V.: Which ones? Artists from Talsi? M.S.: Yes, yes. Žanis Sūniņš, Jēkabs Spriņģis, Andris Biezbārdis, Fricis Makstnieks. M.V.: Has anyone ever commissioned a portrait? M.S.: There was one. Someone wanted to surprise his wife. He gave me his wife's photograph. M.V.: I've seen lots of animals in your works. How do you draw them? M.S.: I do them from memory. M.V.: How do you imagine what the religious figures look like? M.S.:: By remembering what I've seen, in films, in other artists' pictures. M.V.: How big are your largest works? M.S.: Some 50 centimetres. M.V.: And the smallest? M.S.: The size of a postcard. M.V.: Which ones are easier? M.S.: The smaller ones. M.V.: What do you prefer working with - pencil, Indian ink, watercolours? M.S.: If I'm honest, it doesn't matter much. M.V.: You don't have a favourite technique? M.S.: No, it's quite all the same to me. If I get bored with one technique I switch to something else. M.V.: And you don't do woodcarving anymore? M.S.: Not exactly, it's just that I don't have the time right now. I have to work on the Ģipka things. M.V.: What do you mostly do your works on - paper or plywood? M.S.: A bit of everything. On paper, and on cardboard, and also on plywood. I've carved plywood. M.V.: Do you tint that plywood? M.S.: I don't even tint it. I mark it in pencil, carve it and then put varnish over the top. I shade some bits with a pencil. M.V.: Have you ever counted how many works you have? M.S.: Not in any kind of detail. I've calculated a bit and know approximately how many there are. It could be somewhere around a hundred. I used to draw greeting cards and give them to people; now I give away older works. I touch them up a little where necessary and give them away, to make space for new works. M.V.: How long do you take to create a piece? M.S.: There have been works which have taken some three weeks, but others can take a week. The one I am doing now is taking longer. M.S.: How easy or difficult is it to pick up and start doing something? M.S.: It varies. It hasn't ever been too easy. The start is always fiddly. Sometimes it will take me past midnight. M.V.: Has anyone criticised you? M.S.: Not quite. When my grandmother was alive, she did sometimes criticise. But I always stick to my own opinion anyway. You can't go about listening to what everyone is saying. | |

| go back | |