|

|

| A clash of visions Margarita Zieda, Theatre Critic | |

| A “clash of visions” – this was the guiding principle for the programming of the international festival of theatre and contemporary performing arts, Foreign Affairs, which took place in Berlin at the end of September and for three weeks in October, combining views about today’s world and what’s happening in it from the perspective of artists living in Latin America, Asia, Africa and Europe. The artistic director of the festival, Belgian Frie Leysen is a legendary personality. Almost twenty years ago she began to develop a completely new multidisciplinary festival format in which the arts freely crossed the boundaries of their own areas, combining with others and opening up new ways of looking at art and the world. In 1994, she founded and for many years developed the Brussels international festival Kunstenfestivaldesart, which has a programme comprising games and visual art works, and has been a platform for experiments and new works, some of which were created right there on the spot. | |

Brett Bailey. 2012 Photo: Koen Cobbaert Publicity photos | |

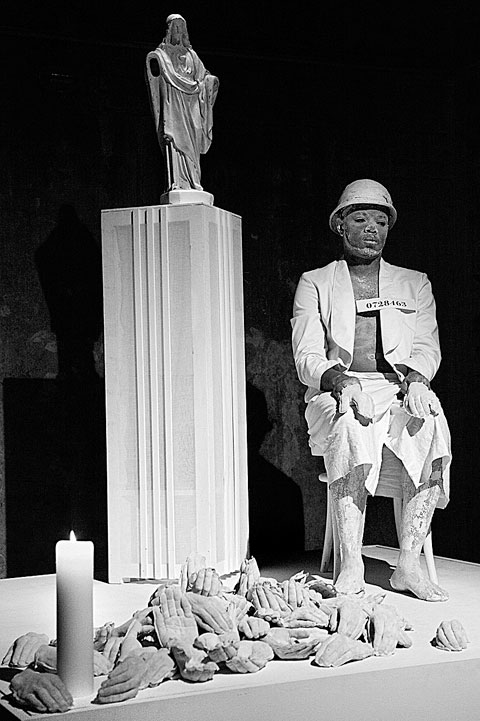

| People began to call festival organizer Leysen a curator, which has become a common notion in the visual arts and exhibition practice, but not in the theatre. She has tried to distance herself from this designation, explaining that, in her opinion, a curator first of all defines a theme and then searches for works that are suited to the revelation of the theme. Leysen operates in quite the opposite fashion – by the antenna principle, perceiving things which are flying around in the air and offering them a platform, because artists don’t have to illustrate her opinions. Frie Leysen says the same thing in relation to the new Berlin Foreign Affairs festival. The nineteen artists that she’s selected are called contemporary witnesses of their time. They also set the tone of the festival, determining the themes to be discussed: loneliness, colonialism, consumerism, ecology, racism, manipulation, a person’s survival within society, our inability to deal with others and things that are different. Brett Bailey’s zoo The most widely discussed work at Foreign Affairs, with the title Exhibit B, had been created in the Republic of South Africa and brought to Europe. Prior to this it had been to Vienna’s Wiener Festwochen Festival, the Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Brussels, the new Theaterformen Festival in Braunschweig and, as stated by the author of the work Brett Bailey, had been praised by audiences everywhere. But in Berlin the work was not well received. Bailey is a white South African artist who declares that with his work, executed by Africans, he stirs up the colonialism complex still existing among Western Europeans which is merely suppressed within the subconscious, and isn’t even close to being overcome. The inspiration for the creation of the exhibition Exhibit B is the 19th century European and North American practice of exhibiting various people from exotic – from the point of view of white people – countries and transporting these live exhibits to annual markets and various festivals. The “golden era” of these anthropological “zoological” exhibitions was between 1870 and 1940. In Europe this phenomenon was related to the growth of colonialism in the mid 19th century, when people who had been transported from the colonised countries were exhibited in zoos and circuses, and in variety programmes. When the National Socialists came to power in Germany they began to put a stop to these “human shows”, they who themselves began to extinguish any sort of “lower beings” from the face of the earth – and it is exactly from similar positions of racial superiority that these living exhibits of people had actually developed. After the Second World War, such exhibits had completely disappeared from Germany. This – in a land where racial superiority had been developed into a people’s extermination mechanism on industrial scale, with the dislike of anything strange or different taken to its extreme consequences. In Germany today, one can still watch a documentary every day, on at least two television programmes, about the horrific people extermination mechanisms devised during the Second World War. So that it is not forgotten. In this context, Brett Bailey with his human zoo had overshot the mark a bit, but didn’t seem to be too perturbed about this. | |

Brett Bailey. Exhibit B. View from the exhibition. 2012 Photo: Anke Schüttler Publicity photos | |

| Bailey began to develop his human exhibits in 2009, responding to an invitation from the Vienna festival to develop a new work, leaving the theme itself up to the author. Here then Bailey let loose with his old interest in these “human zoos”, with the goal of telling Europeans that they still look upon the people of Africa as animals. Conducting his research on the internet and making do only with whatever has been written in English, as Bailey doesn’t know any other languages, he began to develop works for German and French-speaking countries. A story that he’d found about the Nigerian Angelo Soliman, born in 1721, enslaved and transported to Vienna, served as a powerful impulse. In Vienna, Soliman became known as a historian, philosopher, scientist and freemason. He became famous, a trusted confidante of Archduchess Maria Therese, and to the outstanding composers Josef Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – simply a friend. When Soliman died, he was mummified and put on display in the Imperial Natural History Museum in Vienna. In creating the exhibitions of people, Bailey had only one the aim: that nobody would think of saying that it all happened so long ago, and I have no connection with it at all. He is trying to draw the line of racism right up till today. And here his thoughts stop with those seeking asylum, those who are being put onto planes and sent back to Africa by European authorities, and to a series of murders which have been committed by Western police whilst dealing with illegal immigrants. The exhibition Exhibit B, says the artist, reveals “the history of racism and the feeling of Western superiority over Africa, which degrades Africans as objects and sub-humans to justify colonialism, the destruction of African society and, finally, the extermination of black people in the name of progress.” The exhibits created by Bailey develop from stories, and a separate installation is devoted to each. These stories reveal how a person is caused to become an object – a sexual object, a work object and so on, and that the chain extends from ancient times up till today. Bailey’s installations are artistically carefully finished; after all, this artist was awarded a gold medal (for design) in 2009 at the most important stage design exhibition in the world – the Prague Quadrennial. For his exhibitions, Bailey always seeks out a special place in the city environment – in Vienna it was the Ethnographic Museum, in Brussels – a church. The Berlin exhibition took place at the city’s small reservoir, which rises up like an invisible tower as it is covered with earth, and from the inside reminds one of a fortress. On the outside it is overgrown with briar-roses, a park has been created at several levels, and at the very top, where a pleasant view of the city opens up, children play, adults meet and not many even suspect what Brett Bailey has developed there, underneath. The majority of visitors to this exhibition have no idea what is waiting for them. Although, having received a number and sitting down in what seems to be a waiting room, waiting for one’s turn to be announced, the viewer is already being led into the event – before their very eyes, in a gigantic glass box like a showcase, a seminaked dark skinned woman covered in a shiny substance is revolving in spooky semi-darkness, lit up from below by white and blue beams which makes her look like a demon. Visitors to the exhibition go in one by one and are not protected by being in a group. Very quickly for each this raises the question– how far are you prepared to accept the perspective which Brett Bailey has forced on you? Because this is an exhibition where the viewer doesn’t have many options: either you are prepared to look at the people exhibited as objects, through your stare repeating the process of people’s degradation into objects, as so many times mentioned by Bailey, or you get out. And here we are not talking about the added difficulties that Bailey has subjected exhibition visitors to – the people degraded to being objects in the exhibition don’t exist there in neutral mode at all. While looking at the people exhibited, you meet their gaze in return. Bailey said that with his “actors” he is also doing the work of a therapist, so that they don’t develop a lasting mental trauma from taking part in the exhibition. | |

Brett Bailey. Exhibit B. View from the exhibition. 2012 Photo: Anke Schüttler Publicity photos | |

| As the viewer you feel bad and guilty in any case, unless nature has endowed you with the same sort of good faith as the little man who entered the exhibition just before me had, and who, standing in front of an installation, continued to study the people with the same sort of unfeigned interest as he did the objects on display. Coming from a country that has also experienced colonization, it’s not difficult for Latvians to play out this scenario in their imaginations, with the one difference being that Latvia as a country was not a colonizer, but itself was a colony for many centuries. What would it be like if one of our artists placed Latvians in showcases and arranged them into an exhibition for transportation to Germany or Russia or Sweden, in order to shame these countries both about what they’d done in the past and about their attitude to the poor Latvians as inferior beings, which continues even now? And similarly to Bailey’s situation, it would be the most appropriate if the artist who created such an exhibition was a Baltic-German or a Russian living in Latvia. In conversation with viewers the artist was told that he himself, in essence, degrades people to being objects with his exhibition, that it’s not the poor viewers on whom he has forced this viewpoint. Bailey expressed surprise, because he himself doesn’t see it like that at all. Furthermore, in all of the countries in which his exhibitions had been on show, viewers had been, yes, shocked, but had also given him a lot of praise for this work. Asked what the difference was between the fee that he receives as the creator of the exhibitions, and what is received by the objects in the exhibitions – the Africans, Bailey just shrugged his shoulders and said that he didn’t know. A pianist in nowhere land Another artist – Italian pianist and conductor Marino Formenti, who was invited to Foreign Affairs with his work Nowhere, had also, to some degree, turned a person into an object. But, even if so, then it wasn’t anybody else but him. The path of Formenti’s art, too, has led him through “A class” art event venues. He has sat at the piano together with the New York Philharmonic as a soloist, has performed at world music festivals of the highest artistic level – at Lucerne and Salzburg, conducted at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala and Vienna’s Musikverein. But, Formenti says, he is so tired from running this kind of life that he doesn’t even get to make music. For Foreign Affairs, he’d decided that for three weeks he’d devote himself only to the thing he was, after all, created for – and that is music. | |

Brett Bailey. Exhibit B. View from the exhibition. 2012 Photo: Anke Schüttler Publicity photos | |

| And so Marino Formenti entered into a little wooden building constructed next to the festival hall. The “mobile house” had been nailed together by Japanese artist Kyohei Sakaguchi from materials salvaged from a rubbish tip, achieving an unbelievably clean feeling on the inside. For three weeks, every day from 11am till 11pm, Formenti played the piano there, leaning against the trunk of a chestnut tree which had “grown” into the little house. He played music, had lunch, rested, played again, had dinner and lived. There were pillows and mattresses on the floor of the little house, and chairs. Whoever so wished could stay there for hours, and days, and weeks together with Formenti, and listen to the sound of this person’s world. Observing the people who came in, it became evident that this doesn’t happen that quickly. Although you don’t have to buy a ticket to enter, nearly everyone who came in acted as if they owned it, massively taking over the space – opening a bag noisily, sniffling, loudly leafing through the programme to find out what the hell was actually taking place here. People today are so obsessed with themselves, that quite a long time passes until they are able to be quiet. And an even longer time passes until they begin to listen. And even longer – until they begin to hear. The music Formenti plays is very varied. It includes compositions by 20th century composers John Cage and Morton Feldman as well as works by 18th century composer Francois Couperin and many early Baroque pieces. And I read in the performance programme: “There are some wonderful compositions by 16th century composer Thomas Tallis, in which the first five minutes of the music and the last five, or other five minute sections somewhere in the middle of the work, are so wonderfully similar to each other, and yet they are as different as the leaves on a tree.” Every so often a chestnut audibly bounces on the roof of the little building, it’s autumn, and the days have drawn in, but each person has as much time inside the little house as they wish to allow themselves. “Why is a human being the only creature in the world that perishes if it doesn’t have money?” asks the constructor of the little house Sakaguchi, at his exhibition in the building next door. Translation into English: Uldis Brūns | |

| go back | |