|

|

| Catapulted into a feast of the Baroque Margarita Zieda, Theatre Critic | |

| Berlin’s Komische Oper finished this season with a production of George Frideric Handel’s opera Xerxes, after which the audience left the hall happy and vitalized – which hadn’t happened for a long time. Even two of the grumpiest German critics evinced a child-like enthusiasm in their reviews, about the unexpected arrival of something special into their everyday lives, something like a miracle. The creators of this production of Xerxes – director Stefan Herheim and scenographer Heike Scheele – are known also in Latvia. In 2006 they produced for our National Opera Das Rheingold, the first part of Richard Wagner’s opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, which at the time was received altogether coolly and grudgingly. Meanwhile the conceptual idea for a production of Wagner’s opera Parsifal, which the creative team tried out in Riga and further developed in Bayreuth, in Germany became the musical event of the year. | |

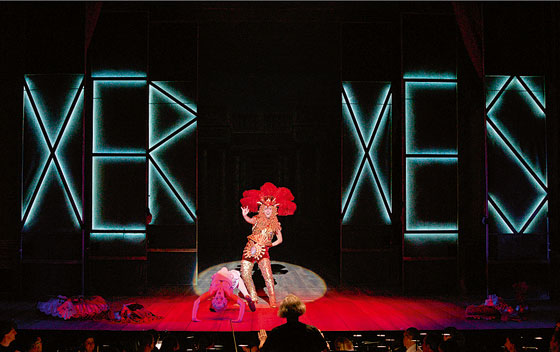

View from the performance of Handel’s Xerxes at Komische Oper. Berlin. 2012 Photo: Forster Publicity photos Courtesy of the Komische Oper Berlin | |

| Stefan Herheim became internationally recognized by way of a scandal that is painful for an artist: at one of the most respectable festivals in the world – the Salzburg Festival – in 2003, his staging of Mozart’s opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail aroused a wave of noisy boos of derision and indignant protests during the performance itself, not to mention the storm of whistling at the end. Meanwhile on the stage a celebration of enthralling, surprisingly rich and unrestrained theatrical fantasy was taking place. Having studied the cello, grown up in opera and developed his own puppet theatre, at the age of twenty four Herheim set off to study opera direction with some outstanding masters – an experience which gave him creative freedom and unshackled his love of play. In his stagings he submitted himself to following the spirit of the work to be interpreted, rather than its letter. In Die Entführung aus dem Serail the director had decided to depart from the activities of abduction and release which are written into the opera’s libretto, and to tell a story that is closer to Mozart in its essence: it is an existentially bleak story of a man meeting a woman, a story of initiation that balances on the border of tragedy. In Herheim’s production, one man multiplies into tens of men, one woman – into tens of women, telling the common story that unites all people. Initially disdained, Die Entführung aus dem Serail became one of the longest running works at the Salzburg Festival, remaining in its repertoire for many seasons. Now Herheim is considered to be one of the top ten most interesting opera directors in Europe, and stages productions at the most highly-regarded European opera theatres. Excavations from the past Working with opera in the new millennium, Herheim became more and more interested in what had happened with these works in the past, including the period in which the opera was written, the personality of the author, how the opera was received by its first audience, and how it was regarded by following generations. All of this wealth of history then began to enter into Herheim’s productions, unfolding vast panoramas and cultural historical layers of the period, creating expansive performances with diversified content. It was specifically at the Latvian National Opera in Riga, in 2006, that Herheim tried out for the first time a risky pursuit – the staging of Wagner’s opera Das Rheingold, looking at the work through the perspective of the history of the development of the Bayreuth Festival which had been created by the composer. The Bayreuth Festival Hall was built over four years, from 1872 to 1875, for the performance of Richard Wagner’s tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen. After this, in accordance with Wagner’s wishes, the festival hall was to be burned down. Luckily for the next generations, however, this didn’t happen. | |

View from the performance of Handel’s Xerxes at Komische Oper. Berlin. 2012 Photo: Forster Publicity photos Courtesy of the Komische Oper Berlin | |

| This operatic work set out on no lesser a challenge – how to transform a person, over the course of four evenings making the public experience through gods and mythological creatures all of the lowest human passions, greed, games of power and money, in order to, by the power of catharsis, them once and for all from everything that prevents them from being Human. In his production of Das Rheingold Herheim projected Bayreuth itself onto this arena of the lowest urges by placing the Bayreuth Festival Hall on stage instead of the castle built by giants, and encouraging the audience to think about what had happened with this venue, meant for the radical transformation of a person into a different quality, since Wagner’s time. Both the Bayreuth Festival collaboration with Hitler’s regime in the 1930s and 1940s, as well as what is happening with it today. It’s a different matter that in Riga there weren’t too many viewers who were well enough informed and thus had food for thought about the spiritual peripeteia of the Bayreuth Festival. The Das Rhein-gold which took place in Riga without the tiniest whiff of scandal, and which scarcely could have done so in Germany with the same tranquillity and peace, gave Herheim the courage to implement this same idea a few years later in Bayreuth. In 2008 he produced Richard Wagner’s farewell opera Parsifal, the composer’s legacy to humanity, and put Bayreuth and Wagner’s house Villa Wahnfried on the Bayreuth Festival stage again, making one think about the sources and reasons for spirituality, and the power of religious beliefs, and why they die out in places and in people who had been created for higher goals. Wagner once wrote about his Parsifal that this was his attempt to rescue the essence of religion through art. | |

View from the performance of Handel’s Xerxes at Komische Oper. Berlin. 2012 Photo: Forster Publicity photos Courtesy of the Komische Oper Berlin | |

| In a survey of international critics by the Opernwelt magazine, the Parsifal produced in Bayreuth by Stefan Herheim and his scenographer Heike Scheele was recognized as the year’s most powerful opera production, and Scheele’s work as the year’s best scenography. From historical expansiveness back to primary sources Following Herheim’s multi-layered performances–labyrinths, his latest production, George Frideric Handel’s Xerxes at Berlin’s Komische Oper, surprises us with its simplicity, the absence of a search for intellectual complexity, and the great joy it creates in its audience. Xerxes is the kind of performance that makes people happy and thankful that they’ve been able to experience such an evening. Herheim and his scenographer Scheele catapult the viewer into a Baroque period theatre similar to what it would have been like when Xerxes was produced for the first time at the King’s Theatre in London in 1738. At the time, the opera was not a success with audiences. It was performed only five times and then disappeared from Europe’s stages for two hundred years. In contemporary stage practice, interest in Baroque opera was revived only relatively recently, about twenty or thirty years ago. At that time, there was great enthusiasm for researching and trying to understand what was the authentic sound of these operas. Instruments of the time were sought out and there were attempts to replicate new ones. The interest in authenticity was directed mainly towards the musical sound, while the stage interpretations tried to stay in step with the spirit of the times. In most cases this meant that the workings on stage were transferred to modern times. This meant putting to Baroque music the modern-day person with their modern clothing, thinking and behaviour, so that in this way the stage work from long ago would be made more approachable for the appreciation of today’s audience. Over the decades the “modern people in modern ways of life” put on stage in ancient operas have become so threadbare that they have for the greater part become clichés, the word for which is – boring. And then, from a completely different direction, an unexpected freshness returns: from the original period, about which there is no information in detail, as no records of performances were ever preserved. But the paintings and engravings of the performances which took place then have remained, fascinating us with their magnificent theatrical scope and splendour. Visual evidence about the stage machinery which made it possible to create miracles has been preserved. This is also where Scheele and Herheim start, in their theatrically creative restoration, seeking to stage Handel’s Xerxes as it was happening in a theatre from the time the opera was written, at a time when theatre was a splendid, visually sensual feast, of a kind which has never again been repeated. When celebrations were not only an important component of an individual’s life, but also of a nation’s, and in extreme cases they could even continue for a whole year – as happened with the wedding of Austria’s Kaiser Leopold I and Spain’s Infanta Margarita Teresa. | |

View from the performance of Handel’s Xerxes at Komische Oper. Berlin. 2012 Photo: Forster Publicity photos Courtesy of the Komische Oper Berlin | |

| Horse ballets, sheep games, gods and beasts, gigantic catastrophes, sea monsters, pyrotechnic symphonies, dancing clouds, sophisticated machinery, stacked up high into the sky. The vertical line develops from the people’s joy in observing miracles. Nothing in this feast is lasting and permanent, everything emerges and then disappears again so that something else can come into existence. The sense of the life of an era is reflected in the opera theatre, like in a magnificent illusion machine, with the wars and catastrophes of the time leaving behind them a real feeling of the impermanence of everything. And at the same time the opera theatre is like a grandiose confirmation of the completeness of existence, in which every moment is vibrant and fulfilling. At the time he wrote Xerxes George Frideric Handel, who actually died a very rich man, was in financial ruin, forced to his knees by life. But nothing about the twilight of the author’s existence is evident in his opera. Quite the opposite – it is a humour-filled, optimistic story about the fact that love is possible, especially for those people who love. And neither intrigue nor the might of hierarchical powers is able to change anything, as love is a completely irrational thing which can’t be grasped and led by logical action. Anguish only enters the music when certainty is lost about whether love was real or only an illusion. Still, Handel’s Xerxes finishes with a confirmation of joy. It is not like that in Herheim’s and Scheele’s Xerxes, which for almost three hours offers a feast of viewing created by sensuous and luxurious fantasy for the audience, without forcing us to look into any deeper existential abysses. In the never-ending world of transformation, joy and laughter, a reminder of Baroque mortality arrives harshly and unexpectedly, right at the very end of the performance. With the arrival on stage of a choir in modern clothing, all of the beauty is suddenly wiped away, as if a broom had passed through. These people aren’t dressed in any particularly unsightly way. They look just like the people you’d see nowadays out on the street. In real life, from which something wonderful has disappeared. Opera as an art form is not a child born of the poorhouse. Created and fostered under the most expensive conditions by the minds, hearts and ambitions of aristocrats, lavish celebrations are inherent to operatic theatre in its very genes. At its inception the art of opera reached out with nothing less than the complete relaying of the sensuous world. Over the centuries all of this began to diminish, changing to quite the opposite – to a reflection of the non-sensuous world on the boards of the stage, and also to a massive onslaught of emphasized tastelessness and ugliness. Opera has remained the most expensive form of art, yet in a paradoxical way these days on so many evenings it demonstrates, as regards the broadness of its artistic intentions and creative thinking, the complete opposite – that is, poverty. Berlin’s Komische Oper with its new intendant, the extravagant Australian director Barrie Kosky (still deemed an enfant terrible), begins its new season in September with three Claudio Monteverdi operas – L’Orfeo, Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria and L’incoronazione di Poppea. All of them will be performed on the one day, one after the other, and to the same audience, with the assumption that this kind of public continues to exist in great numbers in spite of the myth of the five-minute attention span perpetuated about the people of today. The kind of person who is ready to abandon themselves to magnificence – to devote their entire day to the world of Claudio Monteverdi. The trilogy of performances will commence at eleven in the morning and finish late at night. Translator into English: Uldis Brūns | |

| go back | |