|

|

| The beginning of another history Elīna Dūce, Visual Art Theorist An upside down conversation with artist Braco Dimitrijević | |

| The shoes have found their place in the boats. The portrait of a passer-by taken in Riga has been hung on the wall of the barn at Cēsis Castle. We are sitting in the shade of the barn and talking. About everything: about geniuses “without faces”, frequent flying, skiing, languages… A bit chaotically. My conversation partner would say that everything is connected, and no subject or event can ever be separated from another. Moreover, right now this seems much more important than the Venice Biennale exhibitions he took part in in 1976, 1982, 1990, 1993 and 2009, or Documenta 5 (1972), Documenta 6 (1977), Documenta 9 (1992), and yet other achievements which would be considered worthy of discussion on our standard scale of values. Braco Dimitrijević: “Art speaks with the speed of light.” He likes to say that he was born at the crossroads, i.e. in Sarajevo in 1948. Time and place definitely matters, but even more important is that fact that he is the son of Bosnian architect Jelena and well-known painter of modern art Vojo Dimitrijević. Important, because from childhood he was steeped in the art that surrounded him, the modern art albums he found on his father’s bookshelf, conversations overheard and things seen in his father’s studio. Before long, he himself became a practitioner, working at great speed in that same studio and painting in expressionist style. A real child prodigy, interviewed by the local newspaper at the age of five, the subject of a 20 minute film by Sarajevo’s Filmske Novosti Braco Dimitrijević. Little Painter (1957) and who, at the age of ten, had 40–50 oil paintings on show at his first solo exhibition. After his eleventh birthday, Braco began to question the attention being paid to him, and concluding it was all down to his father, gave up painting. Forever. As a teenager, he discovered the joy of speed as a downhill skier. The courage, quick decision-making and precise sense of space and time learned in racing served him well later on, in the arena of art. B.D.: “Borders of any kind have always been somehow unnatural.” As a young traveller, Braco Dimitrijević did not understand why borders were necessary. He was even more confused about the custom for ships and yachts to hoist courtesy flags when entering foreign ports, so he dreamed of replacing national flags with an international one. Thus The Flag of the World was raised above a boat heading towards Dubrovnik in 1963. This flag, made from a paintbrush cleaning rag, has gone down in Dimitrijević’s biography as his first conceptual work and his first creative intervention in an urban environment. It is significant that subsequent works by Dimitrijević have involved breaking accepted symbols and stereotypes, replacing official codes with personal ones. Before ascending the Olympian heights of conceptual art, he first studied physics, electronics and mathematics, then realised that scientific method didn’t suit his creative temperament, and finally awoke to the realisation that he wanted to study art. B.D.: “Every energy turns into a picture.” Although Yugoslavia was comparatively open to Western and contemporary artistic ideas in the 1960s and 1970s(1), Dimitrijević did not get the inspiration he needed at the Zagreb Art Academy. The long hours of drawing and scrupulous compositional studies did not answer his burning questions – what is the role of the artist? And what should art be? B.D.: “The whole concept of education and culture is based on obedience to authority and the hierarchy of values.” As a first year student, Dimitrijević broke the academy’s rule not to exhibit any works before graduation. In 1969 he exhibited an installation, or as it was called back then a postobject(2), at the Galerije Studentskog Centra (Student Centre Gallery). His interests included non-material, ephemeral expressions which hovered around the boundaries of authorship. Art historian Nena Dimitrijević recalls Braco signing his name in the dust left on the wall after an exhibition of a teacher’s paintings to create Dust trace of the painting of F. K.(3) There is no consensus on the authorship of this work/idea, however, because Braco’s friend Goran Trbuljak (1948) also took part in the event and did the same thing.(4) The authorship is hard to prove and could be argued – who really “discovered” the dust? And after all, the dust was located within the frame of F. K.’s painting! | |

Braco Dimitrijević. Sailing to Post-History. Installation at the art festival Cēsis 2012. 2009 | |

| B.D.: “I actually do not see myself as the producer of objects, but as the creator of a vision.” Dimitrijević values highly the element of chance. In Zagreb, he poured some plaster dust on the road, then a car accidently drove over it and blew away the pile of powder. This “collision” was photographed, and since for a few microseconds the plaster dust assumed the shape of a cloud, it was dubbed Accidental Sculpture (1968). A similar thing happened with a milk carton. Dimitrijević stopped the car, and since the driver Krešimir Klika was pleased with the soggy result on the asphalt, it was dubbed Painting by Krešimir Klika (1969). Similar going out “on the street” efforts or rather evasion of the usual system for exhibiting art were also being tried out in the West in the 1960s. Situationists and earth artists protested against the gallery system by going outside it. In Yugoslavia, artists left established exhibition places to make contact with their audience,(5) occasionally their co-creators, but Dimitrijević was also interested in the city context, the layers of history, ideology and power into which he skilfully “implanted” his message like a plastic surgeon. This sort of intervention in the city’s information space later gained quite a following. B.D.: “Art must be such that people have questions.” In 1969 Braco Dimitrijević and Goran Trbuljak created the Tihomir Simčić Group. This was named after a pensioner who opened the door and unwittingly left his prints on some soft clay the artists were holding on the other side of the door. The initiators of the idea, Braco and Goran, were united in their criticism of the existing art system and the status of the artist. Following their intention that anyone making any visual changes to the norm could join the group, random passers-by became members. This was a calculated strategy, since at the time artistic experiments were to be more safely conducted behind a somewhat mysterious, inscrutable mask. The two young artists wanted to make art more democratic, to lessen the distance between artist and viewer by giving meaning to everyday phenomena, and directing the artist’s role towa art. They sought to demolish the “artistic genius” myth which had evolved since the Renaissance and, like Joseph Beuys and his “everyone is an artist”, to give creativity back to every passer-by. Aware that an annual gallery exhibition was not enough and a museum show would never happen, in 1970 Dimitrijević and his associates arranged with the residents of a dwelling at 2a Frankopanska Street to use the building lobby as an exhibition space. The space was independent of official art bodies and as such was unique in the world at the time. This initiative started off the trend for using places unrelated to art as exhibition venues. Several temporary exhibitions were held at the gallery Frankopanska 2a, the best known of which was At the Moment (1971). In accordance with Dimitrijević’s belief that “eternity is composed of seconds”, it only lasted three hours (from 17.00 to 20.00). Viewers packed the space to see works by rising stars like Giovanni Anselmo, Joseph Beuys, Barry Flanagan, Jannis Kounellis, Sol LeWitt and Lawrence Weiner, as well as Braco Dimitrijević, Goran Trbuljak and others. B.D.: “There are no mistakes in History, but the whole of History is a mistake.” Soon after this exhibition, Dimitrijević submitted two projects for the 6th annual Zagreb exhibition Salon. One of these had failed to secure official approval for several years, however this time it got the green light. In 1971, in a number of Zagreb’s squares Dimitrijević placed six 2x3 m portraits of accidentally encountered passers-by onto the building facades where usually posters of communist leaders were displayed. There were no explanatory texts, and the images led local residents to unthinkingly assume that these were political figures, and to wonder whether there had been an overnight coup and change of government. It soon became clear that the portraits of casual passer-by could be only placed in these locations set aside for the party elite at that specific time, when Yugoslavia was experiencing a “Croatian Spring.” In this dizzying period of thaw, Dimitrijević’s passer-by series cast further doubts on the cult of personality of Yugoslavia’s leaders and stirred people from passivity into questioning the single, homogenous “correctness” displayed in the public sphere. However, after 1971 the political atmosphere grew chillier and more uncomfortable also for the practitioners of New Art Practice(6); as Želimir Koščević recalled, after 1971 a deep silence enveloped artistic creation(7). That autumn Dimitrijević took part in the 7th Paris Biennale. Here the “casual passer-by” began its march to fame. The black and white passport-style photos became images displayed not only on building facades, but also on billboards, sides of buses and metro posters. 1971 also saw the end of collaboration between Braco Dimitrijević and Goran Trbuljak, as their views diverged over artistic methods.(8) Although both believed that art should change people’s thinking, Trbuljak criticised Dimitrijević’s passers-by series as too large and commercial, also accusing Dimitrijević of selling out to the art market. After yet another effort to join the Artists’ Union had failed (thereby leaving him without a studio, social insurance or medical care), Dimitrijević understood that there was no future for him in Yugoslavia and he moved to London, a city which at the time wasn’t on the art market map. | |

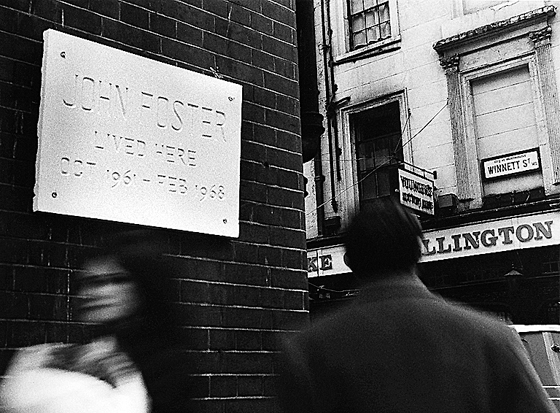

Braco Dimitrijević. John Foster – Casual Passer-By I Met at 10.05 p.m. Memorial plaque, London. 1972 Collection: Tate Gallery, London Courtesy of the artist | |

| B.D.: “Man has survived because there have been artists.” In order to escape the fate of being “dumb as an artist”(9), in the mid 1960s the New Generation sculptors from St. Martin’s School of Art made it fashionable to enrol in the sculpture class which espoused unorthodox artistic ideas. This was the school that Gilbert and George, creators of “living sculptures”, as well as Richard Long, known for his walking sculptures, had attended. Dimitrijević also studied there, although by the early 1970s the legendary sculpture course was on the wane and had turned into a workshop for making formal painted metal sculptures. The different environment (here the politicians’ portraits were small and underground, or exhibited as sculptures) forced Dimitrijević to revise his “passer-by” strategy. Soon he began making street signs in which the streets were named after people he had met, as well as memorial plaques featuring a person’s name and the period during which they resided at the address they revealed to the artist. Using the socially programmed codes that make us automatically assume that such a kind of visual emphasis in a city is only applicable to special people, Dimitrijević prompts us to consider whether a casual passer-by is any less important than someone who is currently popular or acclaimed. Perhaps history is mistaken and this passer-by is an unacknowledged genius, just like Franz Kafka who was considered no more than an insurance clerk in his lifetime, yet after his death was turned into a 20th century genius (against his own wishes). Dimitrijević says: “The casual passer-by stands for unrecognized creative potential or the creative person whose ideas were overlooked because they were too advanced.”(10) “The mad scientist”, as Nikola Tesla was once known, died in poverty and obscurity, but is today hailed as the father of the 20th century. Dimitrijević reminds us that while today Picasso has no acolytes whereas Duchamp has many, the situation was the exact reverse in the 1920s, when Duchamp played chess and waited for his time to come. Examples are not hard to find here in Latvia. Recognition has finally come to a man whose hidden “artifices” (as he himself called his works), recently discovered, are prompting a rewriting of Latvian art history in the late 20th century, giving rightful place to a man whose ruling passion was barely noticed by anybody. During the Soviet period, Visvaldis Ziediņš was a passer-by in Liepāja who some may have known as a vehicle painter or an interior decorator. “How can the world be so blind as to ignore these geniuses walking amongst us?” asks Dimitrijević, answering that “Every casual passer-by is my alter-ego, a supplement to my ignorance.” B.D.: “The whole of history is not as rich as one second of Post-Historic time.” Dimitrijević believes that our “monumental history” is a false, impressionistic science in which subjectivity is presented as objectivity. He also considers linear time to be a method used by historians to exclude inconvenient or unknown facts. By using these same history compilation methods or a random selection involving the same forms of presentation – photographs, monuments, memorial plaques etc. – Dimitrijević creates his own history. Dimitrijević summarized his views on the relativity of history (including art history) in his essay Tractatus Post Historicus (1976). He defines “post-history” as an infinite space of truth embracing a multifaceted viewpoint and coexisting, diverse values. It includes both the known and the unknown, moreover “the unknown is the richest field of all”(11). B.D.: “Darwinism would be acceptable if it would imply reverse order.” Dimitrijević came upon the idea of “post-history” after discovering that the answers he sought to the questions that interested him were not to be found in books. He recalled that books published in the mid-20th century made no mention of Kazimir Malevich. “History should be composed of an infinitive number of interpretations of events, so that the difference between the legend – the sum of individual interpretations, often irrational, in which everything is possible – and history – as we know it today with its limitation of “proven facts” – would disappear,” Dimitrijević writes in his essay. He thinks that art history is absurd when considered as a chronological succession of styles, with each new style declared superior to its predecessor, as if one ideal style were possible. Dimitrijević is convinced that compartmentalization by style is a kind of racism in art, since in the age of Rococo there must have been at least one artist following a minimalist aesthetic, but who remains unknown because his taste was out of phase with the majority. B.D.: “I do not want my art to be instantly identifiable.” In his Casual Passer-by series, which has expanded to around 500 works since 1971, Dimitrijević is like a barometer of the city, determining the major “congestion” points of the street network. The images are placed at places of high information saturation, giving the works a context or background which leads the viewer to make mistaken judgements about the role of the person in the photograph; after all, a portrait displayed on a cinema wall must be that of a movie star! Working with classic art materials and methods, and making use of appropriations, Dimitrijević describes his style as “intentional unoriginality”. In spite of the principles proposed in his manifesto which might strike modern people as liable to generate disorder or even chaos, his works have a laconic visual language. As Cornelia Lauf says, “Perhaps the most important thing that he did was show that the notion of medium is irrelevant, and that even marble could become conceptual.”(12) | |

Braco Dimitrijević. Casual Passer-By I Met at 6.07 p.m. Riga 2012. Poster. Art festival Cēsis 2012. 2012 Photo: Elīna Dūce | |

| In 1979, Dimitrijević installed a classic marble obelisk in Berlin’s Schloss Charlottenburg with the inscription 11th of March. This Could be a Day of Historical Importance in four languages. The date was mentioned by a passer-by as his birthday, but no year is mentioned. After carefully going through a list of historic turning points, the authorities found that this was a “free” date and allowed it to be written on the obelisk. Some time later, Vytautas Landsbergis congratulated Dimitrijević for predicting the date on which Lithuania’s independence would be restored. The date could have just as well been “11 September”, or some other day not yet branded within a specific historic period. Dimitrijević deals with our attraction to important dates in his series The Casual Passer-by, punctually recording the hour and minute of the encounter. The collection of the nascent Contemporary Art Museum in Latvia has acquired a work from this series entitled Casual Passer-By I Met at 6.07 p.m. Riga 2012, first shown at the art festival Cēsis 2012. Since there is no mention of a date, or at least the month, on the Western scale of values this becomes an unidentifiable event. B.D.: “Just as paintings have their stories, so too do shovels and violins.” As art dematerialised in the 1970s, many artists began working outside exhibition halls. For his part, as a pioneer of “outdoor art,” Dimitrijević chose this moment to return to the museum scene. In a solo exhibition at the Städlisches Museum Mönchengladbach, Dimitrijević included a bronze bust by German artist Max Roeder among his works. This Could be a Masterpiece (1975) was the first work “borrowed” from another artist to be given a second life under Dimitrijević’s signature. In concluding a purchase contract for the idea, museum director Johannes Cladders theoretically acquired this work a second time for the museum’s collection, this time writing Dimitrijević’s name in the “author” column. The bust thus began living a double life, spending six months of the year as a work by Roeder and the other six months as a Dimitrijević. In his next long term cycle, Dimitrijević incorporated other authors’ works in his own, newly created works. In 1976 Dimitrijević displayed his installation (or constellation as he liked to call it, due to its changing character) Triptychos Post Historicus, consisting of a Kandinsky painting, a piece of timber and the fruit of doubt – an apple. This trinity – an approved artwork from a prestigious collection, somebody’s (their name is usually known) used everyday item (a bike, boots, a piano, a motorcycle, a rake etc.) and a natural element (melons, leaves, eggs and similar) – has remained at the centre of subsequent works in this series, symbolising human life and its relationship to the organic, inorganic and spiritual world. The interaction of these objects should be harmonious, but in reality we cannot treat them all equally, despite the fact that we cannot exist without any of these elements. | |

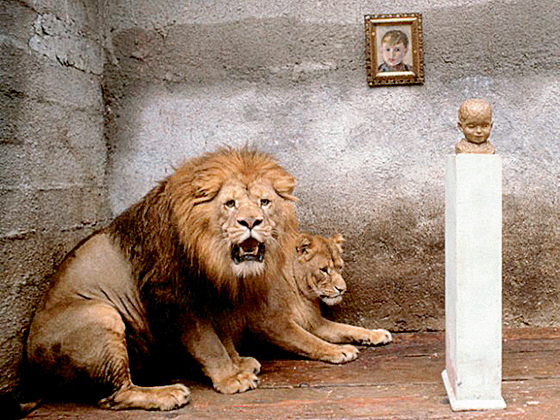

Braco Dimitrijević. Memories of Childhood. Installation 1983 Photo from the private archive of Braco Dimitrijević Courtesy of the artist | |

| B.D.: “The real revolution does not happen when people express their anger by throwing tomatoes at paintings, but when a fruit is gently placed next to a painting.” In 1987 The Times received a hostile letter from a visitor who had attended a Dimitrijević exhibition at the Tate Gallery, accusing the artist of disrespecting Amedeo Modigliani’s The Little Peasant (1918). This painting had been placed in a wardrobe, on top of which was a pumpkin. The letter writer was horrified that a painting, valued at 2.5 million pounds sterling at the time, had been placed in a wardrobe bought in a charity shop. On hearing such figures quoted, few will reflect on the conditions in which this particular painting was kept just after its completion. Modigliani was an artist who lived in poverty and in his lifetime sold his works for a few francs each. By removing the painting from the museum wall, Dimitrijević breaks a deeply entrenched taboo regarding the inviolability of an artwork. The artwork reflects its aura onto the objects, so the fruit is no longer just the stuff of sustenance but serves as a metaphor for the eternal cycle of nature, from birth to maturity to death, more-over it alone has the power of rejuvenation, making it the only immortal thing. “(Instead of the) blind respect we have for the art works in museums: proposed instead is a critical and creative reading of the art of the past and that of the present,”(13) writes Nena Dimitrijević, adding that a previous artwork should stimulate the creation of new works. It must be said that Dimitrijević’s “intervention” in museum collections and the use of various appropriation techniques has left an impact on art today. B.D.: “I make a work with animals to try to learn about men.” Stating that our lives have become too synthetic, by separating the kitchen, the bedroom and the art studio, for instance, or by counter posing art and nature, Dimitrijević’s reference to the “post-history” ideals of harmony and unity is an attempt to bridge this divide. At London’s Waddington Gallery in 1981, amidst paintings by Picasso, Monet and Matisse, two peacocks displayed their magnificent tail feathers as part of the work Dust of Louvre and Mist of Amazon. The involvement of animals – snakes, elephants, flamingos – has often bewildered people, but Dimitrijević proved that unlike the aggression towards works of art exhibited by some humans, if you put a painting in a lion’s cage at the zoo, the lion will not attempt to eat or destroy the work. Declaring “the Louvre is my studio, the street is my museum”, he breaks down spatial boundaries. In 1973, Dimitrijević spent the night in Zagreb’s Gallery of Contemporary Art. He wished to highlight our desire to artificially separate natural things, insisting, firstly, that the museum was a place to live and work, and not just somewhere to store finished products, and secondly, also to demonstrate every individual’s need for creative expression. This position brings the concept of prehistory and “post-history” closer together. | |

Braco Dimitrijević. Le rythme parfait d’Eric Satie Installation. Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes, Paris. 1998 Photo from the private archive of Braco Dimitrijević Courtesy of the artist | |

| In his opinion, the cave inhabitants of Lascaux and Altamire were the complete opposites of our civilisation, in that for them the questions of survival and creative expression were inextricably linked. Modern-day humans have splintered away to infinity their knowledge, in this way fragmenting their world view and making it impossible to make connections or understand the world. Moreover, there were no authors in caves – ideas were freely borrowed and handed on further to others, thereby transcending time. B.D.: “Economy of language enables the artist to communicate fast.” After moving to Paris in the early 1990s, Dimitrijević started a new series of works, continuing with his portraits but shifting to photographs of writers, scientists, artists and musicians, which became part of his installations with objects and/or fruit. Actually we only know the names of these people and their works, because their faces are as unfamiliar to us as the images of the anonymous passers-by. One such combination of three elements with portraits was shown at the 53rd Venice Biennale in the Palazzo Ca’Pesaro modern art museum, and it could also be seen alongside the photo portrait Casual Passer-By I Met at 6.07 p.m. Riga 2012 at the art festival Cēsis 2012 and in the Latvian National Museum of Art. In the installation Sailing to Post-History, the father of Futurism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, suprematist Kazimir Malevich, pioneer of modern literature Franz Kafka, the developer of Luchism (or Rayonism) Natalia Goncharova, the conqueror of electricity Nikola Tesla and surrealist René Magritte are like sails driving boats forwards, but without experiencing the shifting of the boats themselves. In their own lifetimes, these people’s ideas were ignored, disparaged or artificially suppressed. B.D.: “Where would I be if I was following the trends? Definitely not in the position to make them.” In appraising Braco Dimitrijević’s creative work, one probably shouldn’t write a conclusion, because there is no provision for an ending in his travels in “post-history” time and space. Translation into English: Filips Birzulis (1) Starting in 1961, Zagreb hosted the international biennale New Tendencies, which attracted artists like Piero Manczni, Yves Klein, the group Zero and other experimental artists of the period; Želimir Koščević , head of the Galerije Studentskog Centra (also known as the “SC”), organised new kinds of exhibitions; Galerija suvremene umjetnosti was also located there. (2) Šuvaković, Miško. Conceptual Art. In: Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-gardes, Neo-avant-gardes, and Post-avant-gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918–1991. Ed. by Dubravka Djurić, Miško Šuvaković. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003, p. 213. (3) Dimitrijević, Nena. Braco Dimitrijević: The posthistorical dimension. In: Braco Dimitrijević. Ed. by Antun Maracić. – Dubrovnik: Museum of Modern Art, 2004 At website: www.transartinstitute.org. (4) Stipančić, Branka. Goran Trbuljak. Zagreb: Galerije grada, 1996, p. 5. (5) Carl, Katherine Ann. Aoristic Avant-garde: Experimental Art in 1960s and 1970s Yugoslavia. Dissertation. State University of New York at Stony Brook, 2009, p. 60. (6) The term “new artistic practice” was used in Yugoslavia in the 1970s and early 1980s to describe then unusual, experimental methods of art making, including swapping the traditional artist’s studio for the city streets or a space controlled by artists. (7) Carl, Katherine Ann. Aoristic Avant-garde: Experimental Art in 1960s and 1970s Yugoslavia, p. 80. (8) Baljković, Nena. Braco Dimitrijevic and Goran Trbuljak, Zagreb. In: The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia 1966–1978. Ed. by Marijan Susovski. Zagreb: Gallery of Contemporary Art, 1978, p. 32. (9) Dimitrijević, Nena. Braco Dimitrijevič: The posthistorical dimension. (10) Rhetorical Image [Catalogue]. New York: The New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1990, p. 42. (11) Ibid. (12) Lauf, Cornelia. Braco Dimitrijevi and New York in the 1980s: Influences and Coincidences. 2006. At website: www.bracodimitrijevic.com. (13) Dimitrijević, Nena. Braco Dimitrijevič: The posthistorical dimension. | |

| go back | |