|

|

| Boo, boo, boooo... Jānis Borgs, Art Critic An unfrightened flow of thoughts after visiting the exhibition of works by Raids Kalniņš Raids Kalniņš. Lost Loners or Dinosaurs eat up Graves 18.05–08.06.2012 RIXC Media Space | |

| One lovely summer’s day in 1949, my Pa took me to the Mežaparks Zoo for the first time in my life. There I watched with concern a real lion which had just decided, I don’t know why, to climb up onto a lioness; a bear cadging ice-cream; a crocodile as immobile as a log of wood; some jovial red-bottomed monkeys; some nastily squealing peacocks... And then suddenly everything was over and we headed towards the exit gates. My bottom lip began to twitch, bitter tears sprang from my eyes like fountains, and I don’t think I omitted a bit of screaming - how could I leave without seeing the very thing I’d hoped to come here to see? It was the Devil that I had longed to see in the first place. This animal, for I was convinced he was one, up till then I’d only regarded with some excitement in a picture book of Latvian folk stories. In the evenings my mother used to read it to me at my bedside before I went to sleep. In my mind, the Devil was quite a pleasant and endearing creature, even though a capricious rogue also. Taking into account the Devil’s horse’s legs, long tail and horns, as he’d been pictured, I logically deduced that at the zoo this beast should be located somewhere among the cows, goats or bison. After Papa explained that he was only a storybook figure, I was crushed by the revelation of how all adults, as it turns out, tell dastardly lies! You can’t believe any of them! | |

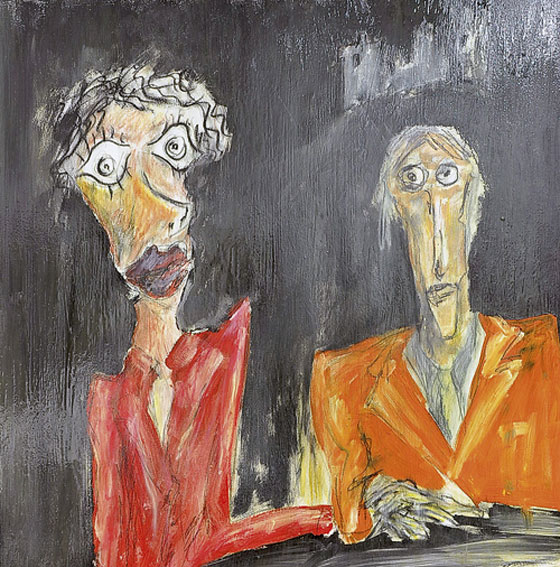

Raids Kalniņš. Dinosaurs eat out graves. Graphite, watercolour on cardboard. 2012 Photo from the private archive of Raids Kalniņš Courtesy of the artist | |

| These recollections (and also to some degree this bitter memory) resurfaced whilst inspecting the quite Satanic paintings and drawings Raids Kalniņš at the RIXC Media Space. They turned out to be much closer to the other devilry I experienced in childhood. Grandmother regularly dragged me to church along with her. There, in the sleepy flow of infinitely boring sermons and the wailing hymns of elderly ladies, my imagination was stimulated by the images from Bible stories hanging on the walls. What looked like firemen in shiny helmets were nastily tormenting and jabbing at a naked man with their spears. Then they cruelly nailed the chap to a cross. He must have been a scoundrel or a murderer. Grandmother, however, later turned everything upside down – the firemen were Romans, but the scoundrel who was nailed to the cross was called Jesus and he, lo and behold, was our Saviour. In other words, a goodie, “one of ours”. But I also saw my old friend the Devil in those church “comics”, who, surrounded by the flames of Hell, was tormenting the sinners that had already arrived there in all sorts of ways, rampaging wickedly like some rascal. Quite like at Raids Kalniņš’ exhibition. A deeper inference emerges from this about possibly Catholic roots of the artist’s work. Although the author himself points to demonic influences from childhood, and links with the world of comics. Perhaps a psychologist, on observing these infantile facets of character, would also have some comment to make? In truth, looking back in history the Catholic Church knew how to scare people, at times no less impressively than is nowadays done by the cinema or television in the horror films or news summaries every evening. And if this were not enough, then Kalniņš also pours some oil onto the fire. Look, for example, at the sculptured images of many a Romanesque church or in paintings of the Renaissance, where Satan like a class enemy never sleeps, waylays people and is happy tearing at the sinful flesh of the poor suffering people. Occasionally something else amusing appears. The Almighty or the chief “commander”, like some kind of SS officer at a recently despatched echelon of prisoners at Auschwitz, is sorting out – you’re good, you’ll do, so you will go this way (to Paradise), but you, the bad one, will head for the gas chamber (or Hell). No godly forgiveness of sins here. In church art, it seems, a kind of dubious contradiction appears as regards the highest ideal, where everybody should be equal before God. The richer the Western person and their society becomes, the more swiftly the use of devils and hell to scare has decreased. Thus, if I’m a generous benefactor to the church, I really won’t, in any way, appreciate reminders of my sins (and for my money at that) and unseemly references about a camel that will sooner pass through the eye of a needle, than I – feudal lord, merchant, banker, businessman, parliamentarian or Mafioso and corrupted person – will reach Paradise. A steely formula has now crystallized in Western art, culture and the public consciousness: the more money, the less of Jesus. Devilry has become a part of the commercial culture and subculture. A sort of unending Halloween kind of life has set in. | |

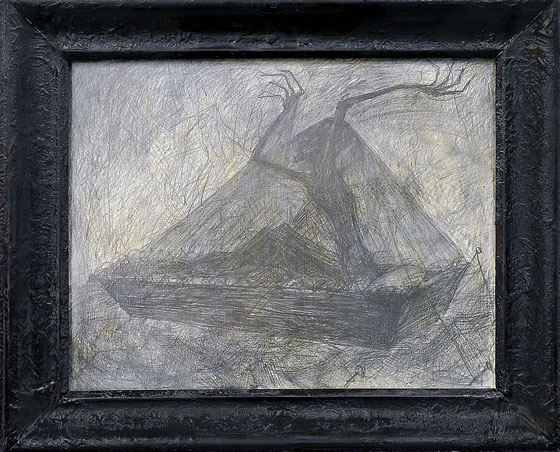

Raids Kalniņš. The Setters (Stage 1. Part I). Varnish, pencil, charcoal, watercolour, gouache on cardboard. 2012 Photo from the private archive of Raids Kalniņš Courtesy of the artist | |

| Looking at Raids Kalniņš’ satanic coffin devourers, resurrected dinosaurs, hobgoblins and corpse munchers from this angle, we sense something germinating from childhood there. Even more so – on the website Artist.lv the artist is described in these words: “Those who don’t know Raids Kalniņš couldn’t imagine that the author of these landscapes of horror and necrophilic motifs is a cheery and kindhearted person, who is usually in a very good mood when you meet him, and when asked about his work is usually happy to talk about it. On the Latvian art scene, Raids is a lone personality, who cultivates a comic-like, serial style narrative format.” So one could say – he’s an entirely “congenial type”, not at all like Van Gogh, who got tied up in the nooses of art like a suicide candidate in a gallows’ rope. Raids demurely watches all sorts of horrors from the sidelines, or even in the comfortable circle of friends and family – he won’t be cutting off his ear nor hurrying to his death in a rye field under a flock of circling ravens. If we look at all this from the bastions of academic culture, the monsters from deep within his consciousness are brought out into art’s light of day in the correct manner and without any assistance of a psychiatrist, in the chattily messy marginalist manner typical of Raids. I even have a suspicion that in Raids’ ransacked coffins, a whole cemetery of art classics and scholars are spinning deliriously as if on a grill, having divined his works from “the other side”, but not out of fear of Satan or the teeth of dinosaurs. But to evaluate something like this now in the permissiveness of post-modernism is completely useless. And for it to be that way, the author of these lines has also persevered in life’s toil and mischief. That’s why we’ll put aside the petty lamentations about inappropriate technique, as it doesn’t even get offered here as a value or as a “degenerate art trick”. And the most essential thing may not even be in the monstrous imagery. Its essence is its stand against our sweets-loving society, which now gets a stinking spray of sulphur or urine directed its way. It is a rascal’s position, now all the more topical thanks to the rascals’ exhibition prepared by curator Sniedze Kāle at Arsenāls. The little art pond is ever in need of hell-raisers, like a wolf that cleans up the forest. It should be added that Raids isn’t a solitary figure here, we have packs of such wolves wandering around. Perhaps Raids’ spiritual peers too – JānisViņķelis, Miķelis Fišers and Gints Gabrāns... In a discussion with Solvita Krese, Raids proclaims right there on Artist.lv: “They torment me continually – those images, and that’s why they are always repeated. First of all there’s the idea – the story. I never trouble myself with drawings and paintings, as I think of them I also make them, put them aside and then don’t pick them up again. I have always liked horror themes. I don’t remember any positive characters from the storybooks of my childhood, and I’ve never found the portrayal of heroes interesting to watch. Why is that forest so dark – there’s something suspicious there, why is it scary there – that’s always enticed me. Gradually I’ve begun to portray this, and it brings me joy. It’s a sort of circle around myself. For example, the landscape with graves, an old man is creeping out of there – I drew him not as a comic figure or in some comic-like atmosphere, but he might be quite funny. But it’s not because I have to frighten anybody.” | |

Raids Kalniņš. The Setters (Stage 1. Part I). Varnish, pencil on cardboard. 2009 Photo from the private archive of Raids Kalniņš Courtesy of the artist | |

| And once again, a parallel from my childhood – in the evenings I liked to give my father a good scare when he arrived home, by jumping out from behind something: boo, boo, boooo... I did get scolded that you can give a person a heart attack like that. But each subsequent boo, boo, boooo was foreseen and expected, and soon lost its frightening effect, turning into a childish joke. Raids Kalniņš’ boo, boo, boooo is also meant to shock the viewer with its punk-like gothic effect. However, the monotonous and samey imagery, the continual repetition of this one mode of expression throughout the course of the exhibition diminishes the surprise (or fright). If you’ve seen one or two works, then in fact you’ve really seen the whole exhibition. The last one is as predictable as the next sweet from a box of black liquorice. The present-day person has already seen so much of this: the evil demons, the “cardboard horror” of Lunapark tunnels of hell, dinosaurs which have re-awakened (and which Raids too, has brought into the light of day in his works) and king kongs, all sorts of vampires, draculas and frankensteins... All of this still had the power to traumatize our innocence towards the end of the Soviet era, when folks spent entire nights vegetating in front of videos, watching the first porno and horror films mixed with copied and recopied Fellini or Bergman films. The lifting of censorship, the opening of borders and the world of the free market shook many out of their infantile paradise and profoundly devalued the world of devils. Hell is something created by people’s own hands on earth, carefully and enduringly maintained. Inquisitions, gulags, drugs, the slave trade, chernobyls, hiroshimas and the endless war “orgies”... At times the Devil even has a handsome countenance. As Amanda Lear once sang – never trust a pretty face... During Soviet times there was a great aesthetics lecturer at the Academy of Art, Herberts Dubins. One theme cropped up in his lectures – a delicacy: evil beauty. He illustrated this with the expressions of Nazi culture, where the heights of demonic design were achieved – in the symbolism, the uniforms and the architecture... And quite enthusiastically reviewed Leni Riefenstahl’s ‘Triumph of the Will’. Soviet students nevertheless had to wait for about a quarter of a century before they could evaluate this sort of thing with their own eyes, in the newly restored Latvia without censorship. Moving along in similar vein, Liliana Cavani’s scandalous film ‘The Night Porter’ appeared in the 1970s. The love story in it, between victim and executioner, developed specifically in the “gravy” of this kind of aesthetic. Or the no less demonic Götterdämmerung by Visconti. In more recent times, evil beauty triumphed most symbolically in the 11 September “super show”. But let’s not attempt to scale those Wagnerian heights. In his art, Raids is grounded in folk symbolism, like Sprīdītis with a reed-pipe in his hands, somewhat “ethnographic”. His works remind me of the sleepovers experienced in my younger days with relatives or friends. There, whenever it was dark, someone would start telling ghost stories worthy of Edgar Allan Poe: mysterious deaths or cases of disappearance, something about the cannibals who were living right next door and who transformed their victims into sausages and fillets... Until sleep overcame the stiffness of goose bumps caused by the horror stories, and the tormenting swamp of nightmares dragged one by the legs to the realm of Morpheus. What haven’t we experienced. And all the same one wants to hug and kiss Raids’ little devils, little dinosaurs, little loathsome creatures and fiends without fear. It’s good that they are there, without them light would fade and life would lose its sharpness of flavour. But still, let’s call out in a folksy way to monster tamer Raids Kalniņš: don’t try to frighten a hedgehog with a bare bottom! /Translator into English: Uldis Brūns/ | |

| go back | |