|

|

| Admirable human error, or What drinking and welding can lead to Alise Tīfentāle, Art Historian Tom Sachs solo-exhibition Space Program: Mars 16.05.-17. 06.2012. Park Avenue Armory, New York | |

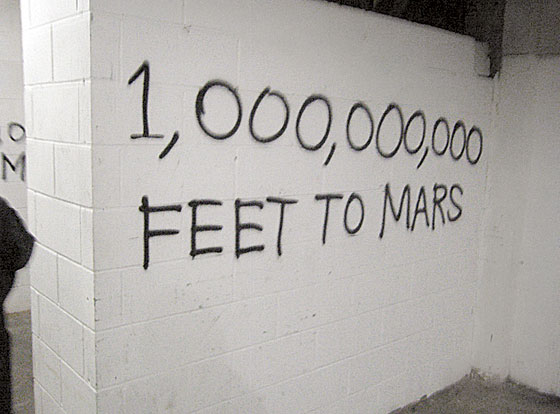

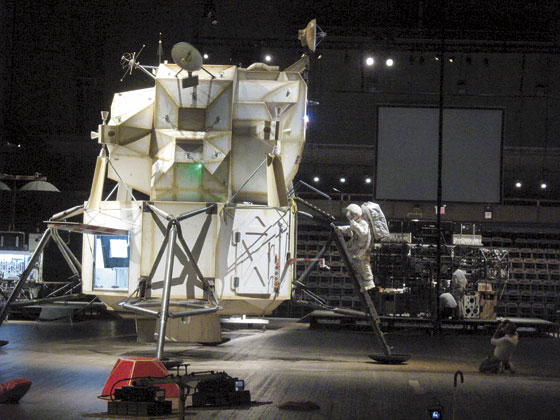

| Since 2006, the Park Avenue Armory has operated as one of the largest contemporary art exhibition halls in the USA. The more than 5,000 square metre large space is a serious challenge, which can demand extraordinary efforts from an artist. Here up till now, for example, artist Aaron Young created an abstract drawing on the floor using motorcycles as “pencils”, Christian Boltanski deployed 30 tonnes of used clothing, and Peter Greenaway installed a kind of memorial to Leonardo’s Last Supper. But it seems that this gigantic hall was expressly created for the solo exhibition, jointly organized by Park Avenue Armory and Creative Time, of Tom Sachs (born 1966). What for others may have been too large, was almost too small for his cosmic ambitions. Civilian Witnesses on Earth and Mars Sachs’ Space Program is partly installation, but even more so theatre, or perhaps performance, with audience participation. The artist himself calls everything taking place at the Armory a “demonstration.” It doesn’t have viewers, but rather civilian witnesses. On the evening of my visit (24 May), the civilian witnesses saw astronauts getting prepared, putting on space suits, the checking of the entire system, the space ship lift-off and trip to Mars, the landing of a space module on the surface of Mars, astronauts getting out and collecting samples from the planet’s surface, and their successful return to Earth. The seats for the civilian witnesses were on both sides of the huge Armory hall – white plastic chairs with the NASA logo (on the backs of which, in accordance with theatre and opera house tradition, one could read autographed names – Led Zeppelin and Michael Jackson etc.). Audio accompaniment was the continuous radio communication of Mission Control Centre (set up approximately like it is in films or serials of the relevant genre – with a wall covered by monitors), between the two female astronauts and a number of assistants. In their communications they used specific military–scientific jargon. Both astronauts regularly reported on how they were feeling and sought confirmation for each operation (“I request permission to proceed. Permission granted, proceed”), in addition to listening to commands and trying to carry them out. The civilian witnesses were issued with a list of the most frequently used acronyms: SAC was The Smiths Audio Cassette, VC –Visual Confirmation, VDS – Vodka Delivery System, MRL – Martian Receiving Lab and RBR was – Red Beans & Rice, etc. First of all there was a systems check. Tango Sierra (T.S. or Tom Sachs) from MCC (Mission Control Centre) requested a VC of the space ship’s equipment status, and the witnesses could then make sure that all systems really were in order, these including the champagne fridge, candles, the library and an Al Green audio cassette. Lift-off followed (an assistant operating a miniature rocket model in front of the video camera next to one of the exhibits), and the Earth moved off into the distance (a toy ball with an outline of continents was raised above the vertically mounted video camera, with an open black umbrella representing the whole of the Universe in the background). | |

Tom Sachs. Space Program: Mars. Installation. Fragment. 2012 Photo: Alise Tīfentāle | |

| The artist doesn’t let you forget that the demonstration is in some way also an entertaining show – while the commander and some assistants tensely observe the space ship’s breaking away from the Earth’s gravitational pull on the monitors, staff politely invite you to purchase popcorn and mineral water. When the mission’s most important stages have been successfully completed, a sign with the word “Applause” lights up above the Mission Control Centre’s wall of monitors. Then, before the astronauts alight, the witnesses are treated to roasted peanuts wrapped in aluminium foil, which have been prepared in the HDNS (or Hot Nuts Delivery System) and are distributed from a stupendous garden wheelbarrow bearing the NASA logo. Having received permission from Mission Control Centre to climb out of the space module, the first jobs to be done were to place a video camera to record operations on the surface of Mars, and to plant a USA flag in the most visible spot. One of the main tasks was to collect samples, and to this end a circle was purposefully cut into the Armory’s wooden floor, where they then tried to fix a dangerous-looking drill-like instrument. As this lengthy process was repeatedly unsuccessful (some of the viewers having already left the hall quite a while ago), Tango Sierra then gave permission to quickly gather some free-standing cardboard “rocks” and stones into a metal box with the NASA logo on it, and to make a hasty return. After a successful exit from the rescue capsule, which a toy helicopter lifted up out of the ocean, both astronauts were taken on a triumphant drive, Tango Sierra and the Mission Centre assistant shook hands with the civilian witnesses in the front rows, and everyone was invited for a glass of champagne, to be received after going through quarantine. Space, Sport and Spirituality The artist admits that he’s always been a science fiction fan – mainly because this genre tells us about life on Earth(1). But then why Mars? In the development of space exploration, one could possibly see parallels with the history of the USA and the American so-called “manifest destiny”, which underpinned and justified the unswerving drive towards the West coast by white Christian immigrants and colonizers. This aspect was also accented by one of the exhibition’s organizers, Creative Time president and artistic director Anne Pasternak: “[The exhibition] honours every mission and every vehicle ever sent to space, while remaining acutely aware of American cowboy pioneerism and the very real ethics of screwing up another place, when our own world is already in trouble.”(2) Sachs is of the view that the entire Apollo enterprise was a Cold War performance for the benefit of the Soviet Union and also, at the same time, American self-actualization – “a twentieth century art project”(3) and “a propagandistic spectacle.”(4) This über-performance, according to Sachs, “was a message about America’s aspirations and fears. Relative to their immense cost, the Moon shots produced little of practical value, their real goal being cold-war cultural and political spectacle, which placed them, Mr. Sachs said, firmly in the realm ‘of the useless and spiritual, just like art.”(5) Hasn’t the time come for putting sport into the same category as well? There are sufficient analogies – both in sport as well as in (Sachs’s) art, where adult men and women get involved in activities which are seemingly unproductive and pointless, while at the same time in both cases there’s an audience prepared to pay to watch these activities. Only that perhaps in sport there’s a little bit more spirituality than in art – one only has to think about the sounding of the national anthem a moment before the deciding competition or the pacifist rhetoric filled discourse which dominates in the public arena of the Olympic Games. | |

Tom Sachs. Space Programm: Mars. Installation view. Mission Control Centre MCC and Landing Excursion Module LEM in the background. 2012 Photo: Genevieve Hanson | |

| Every Friday morning, for the duration of the exhibition, Sachs and his assistants would arrive at the Armoury and put on white sports shoes, white shorts and white T-shirts with the logo “It will not fail because of me”, and energetically exercised for an hour. The New York Times critic Randy Kennedy pointed out that Sachs’ Mars mission could also be perceived as a component of a “new secular religion (?)”.(6) Although discourses in which religion and contemporary art are mentioned in the same breath usually elicit suspicion, Kennedy isn’t the only one who got involved in this perilous kind of speculation. In the Style magazine of The New York Times, Linda Yablonsky expressed the opinion that for Sachs “science is the only true religion and Space Program: Mars is his D.I.Y. temple to it.”(7) Sachs himself talks only about ritual, not religion: “One of the big parts of our space program is ritual. Our main work is ritual, but cocktails, coffee and cigarettes are ways people have of connecting with each other.”(8) Science and Technology Sachs’ main working materials are paper, foam board, plywood, screws, adhesive tape, household items, instruments and everyday items. Captions are written in black Flowmaster pen, in the artist’s handwriting. When the artist is absent and some caption has to be prepared by his assistants, there’s a chart with his handwriting, for its accurate reproduction, in Sachs’ workshop.(9) “There is no cutting-edge technology here. Our space program is expensive, slow and crappy. That’s why it’s magic”, says the artist.(10) And it’s no surprise that none other than Germano Celant (born 1940), the theoretical father of Arte Povera, is occupied with the theorization of Sach’s art. He has praised the use of adhesive tape and foam board in Sachs’ works, pointing out that both materials contrast themselves with the sophistication and longevity concept, which is at the core of traditional works of art.(11) Other critics have also valued the fact that the superiority of physical forms, materials and substance over abstract ideas are emphasized in Sachs’s works.(12) However, it must be conceded that in any case the idea is: in whose name are people heading out into space or creating art. I experienced a revelation while watching how both astronauts toiled away in their heavy spacesuits and large protective gloves, working with a power-saw fixed in an unsteady frame (first of all, they were only able to get it to work after an assistant had been summoned from Earth) and even more unsuccessfully with a dubious looking drill, meanwhile continually communicating on their walkie talkies with Mission Control Centre. Much of what is “hi-tech,” secret and expensive, and meant for superhuman goals in the name of high ideals, often enough stops dead or sticks due to unforeseen circumstances, and even more often due to so-called “human error”. Both on a genuine space mission, as well as in an art exhibition hall. And even when it isn’t a real error, but simply something that doesn’t turn out like it did in the testing regimen. This applies to the numerous less serious and responsible tasks which we undertake every day – so often something goes awry at the wheel of the car or on a bike, at work or play, while exercising or shopping, in the garden with the vegetable plot or by the stove in the kitchen. A person is capable of endless mistakes, of being unable to achieve what they intended or to achieve it only partly. But that doesn’t stop one from striving for perfection. Sachs, too, is a perfectionist – he had brought in as unofficial advisers a few actual NASA engineers, who spoke approvingly of the artist’s ability to “engage in intellectual, conceptual play.”(13) Sachs needed help in transforming a golf buggy into a vehicle with which the Mars explorers could move along the surface of the Red Planet. The planned practical lunch had apparently transformed into a “really fun night of drinking and welding.”(14) What could be more fun than that? It all started with a screwdriver Examining Tom Sachs’ works up till now, first of all one of the earliest must be noted – Quarter Screw (1989), which was respectfully reproduced in a number of copies. The name describes the item itself – it is a screwdriver with a coin in place of the handle. This is the screwdriver Malcolm Gladwell, writer and friend of the artist, uses to open the storeroom of secrets of Sachs’ creative work. The screwdriver as a practical instrument and a work of art simultaneously? Furthermore, “It was capital (the quarter) fused to labor (the screwdriver) with (as always) capital at the head and labor getting the shaft.”(15) Among Sachs’ other early works – such as, for example, a chair made from a shopping trolley Shopping Cart Chair (1993) and Bulletproof Diaper (1994) – homemade guns have a special place (starting from 1995). At that time the political discussion about reducing the spread of firearms was very topical in the USA. On the evening of the exhibition’s opening, Mary Boone, at whose gallery in New York Sachs had exhibited a range of homemade guns, was arrested for being in possession of illegal guns and ammunition. Among Sachs’ works from this period we find also an electric chair W.W.J.B.D. Electric Chair (1999). Celant points out “Its functionality (. . .) underscores the fact that death is not an icon, nor an image (as Warhol thinks), but an actual fact that can always be realized.”(16) This (theoretically) functional object, the only purpose of which is to realize the categorical fact that Celant mentions, in its brutality and directness outdoes the weapons created by Sachs. It has only the one goal. It is interesting how the idea of the death machine regularly returns in art. Relatively recently, for example, young Lithuanian designer and artist Julijonas Urbonas achieved notoriety for his work Euthanasia Coaster (2010). When compared with Sachs’ electric chair, this is just a harmless small model, but, if built to its real size, is meant for pleasant and even euphoric euthanasia, where the whole process is completed by the force of gravity and inertia. In Urbonas’ case, the most ghastly thing of all could be the rational theoretical calculation that is embodied in the elegantly simple form.(17) | |

Tom Sachs. Space Program: Mars. Installation. Fragment. 2012 Photo: Alise Tīfentāle | |

| As a distant analogy to Sachs’ homemade weapons, Germano Celant mentions the gun sculptures of the Arte Povera movement artist Pino Pascali (1935-1968). But there are more differences than similarities: Pascali’s machineguns and cannons, made from found objects, imitated the appearance of real weapons, but weren’t capable of firing. Sachs’ guns, made from found objects, often don’t look like real weapons at all, but are in fact fully functional. Sachs moreover associates violence, which is the main function of weapons, with consumer culture brand fetishism, for example, by making a Hermès Hand Grenade (1995). This was followed by many just as frightening and at the same time moving products – for example, the Chanel Chain Saw (1996, 1999), the Prada Toilet (1997), the Chanel Guillotine (1998), and attractive Chanel, Hermès and Tiffany & Co boxes with the title Giftgas Giftset (1998; gift meaning poison in German and present in English). The attention of the wider community, however, was drawn by a model of a concentration camp in a Prada hatbox, Prada Deathcamp (1998), shown at an exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York. The work was generally misunderstood. Tom Sachs explains: “Growing up in Connecticut, being Jewish wasn’t about being Jewish. It was about shopping. In Hebrew school, the key issue wasn’t Judaism and its history, but the Holocaust. It was like Holocaust school. So it wasn’t that I was insensitive. The message I heard growing up was: “Never let this happen again.” But the rituals we had weren’t Jewish; they were shopping rituals. (. . . ) With Prada Deathcamp, I was not trying to make a piece about the Holocaust – I was trying to expose the way in which shopping has become a religion. We voluntarily line up for the gas chambers of our souls as they load our bodies into the chic ovens of consumerism. It’s fascism not fashion. Prada is the brand that represents it as well as any of them. It’s beautiful stuff for people who have no style.”(18) At the same time Sachs has pointed out that he is in no way against fashion or brands as such. He has developed a good relationship working with Prada fashion house artists (Fondazione Prada in Milan organized a comprehensive solo exhibition for the artist in 2006.). The artist’s collaboration with Nike has been just as successful, as a result of which anyone interested can order Nike sports shoes designed by Tom Sachs for US$385, as well as clothing and accessories.(19) One of the most extensive of Sachs’ works up till now has been Nutsy’s (Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, 2003) – a non-existent, but very possible and comprehensive simulation of a contemporary city, in which, among many other things, there is a McDonald’s fast food stand. Sachs’ source of inspiration is the history of McDonald’s and the biography of its founder, Ray Kroc.(20) In it, Kroc features as an inventor and discoverer, who first and foremost was interested in technology. His goal was the standardization of production, and the nature of the products themselves was of little interest to him. To achieve his goal, Kroc turned to the invention of new equipment: “Kroc was concerned not with making fast food but with how fast food was made (. . .); he was an engineer, not a cook, and the Big Mac is what you get when you let engineers into the kitchen.”(21) It was specifically Kroc’s “do it yourself ethic” which fascinated Sachs. He can construct anything, and in addition the work (the making) process gets exhibited as one of the main features. If screws are used, then they have to be visible. If something is glued, traces of the glue must be visible. Gladwell calls this “craftsmanlike imitation of a post-industrial object,” which doesn’t parody or criticize these objects, but rather “humanizes” them.(22) Sachs’ methods are distantly reminiscent of Thomas Demand and his exceptionally careful work on paper models of interiors and buildings. However, in this case, also, there are more differences than similarities: Demand creates a world only in order to photograph it (after which the models are destroyed). Sachs in turn creates his world and uses it. Demand creates a wonderful illusion – the craftsmanlike side is carefully hidden. Sachs, quite the opposite, emphasizes it. One could also try to understand whether Sachs is just as mad as Matthew Barney. In any case their creative ambitions could be something that they both have in common, as well as an interest in whales and sport (for example, Sachs constructed a huge whale Balaenoptera Musculus (2006), but Barney was inspired by whale hunting rituals (Drawing Restraint 9” (2005)). Likewise one could identify similarities with Thomas Hirschhorn’s work from the 1990s, although Hirschhorn later chose to take the path of much more radical critique.(23) Golden hands without a “real” job The conquest of space began in 2007 with a solo exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills. In it, Sachs played out the Apollo 11 expedition to the Moon. At the time, critics wrote that Sachs’ space program can be admired, but it “resists contemplation,” and furthermore it can be compared with Warhol’s Brillo Box, although it doesn’t quite reach the same philosophical heights.(24) One could perhaps get into a discussion about the philosophical achievements of Brillo boxes, moreover it seems that there are light-years separating Warhol’s and Sachs’ thinking and works. If Warhol placed mass consumer goods on a pedestal, then Sachs focusses a great deal more attention on the product manufacturing process, or the work as such (“I think [work] is really what keeps me sane,” says the artist(25)). Work and the work ethic are at the foundations of Sachs’ upbringing. The artist remembers that his great grandfather, a Jewish immigrant from Eastern Europe, arrived in the USA like many others without a cent in his pocket, and throughout his life just worked, worked and worked. In a way Sachs continues this family tradition, and with every subsequent exhibition confirms that there isn’t anything more valuable than honest, decent work with your hands. As noted by Gladwell, you could get the impression that “It’s as if Sachs forcibly removed himself from the twentieth century and took himself back to the nineteenth,” distancing himself from the opportunities of an education or a career, which may have seemed self-evident to his well-off and successful family, and joining the ranks of manual labourers.(26) Sachs began his working life as a carpenter at the wood furniture workshop of the world famous architect Frank Gehry in Los Angeles. He later moved to New York, where in lieu of paying rent he welded fire escape stairs and repaired lifts for the landlord of his apartment, and found a job as technical worker with the Barney’s department store chain. His duties were to take down decorations, and to clean and repaint display window niches. It was due to the department store display windows that he also first got noticed – when Barney’s invited Sachs to set up the display window and Hello Kitty Nativity (1994) was the result, which besides the Hello Kitty dolls also featured Bart Simpson, all of this being crowned with the McDonald’s logo. Gladwell characterizes Sachs’ creative activity as “pre-post-industrial. It is concerned with the personal act of production at a time when the rest of us are preoccupied with the impersonal act of consumption.”(27) If one turns to this aspect in the analysis of Sachs’ works, one can see in them a certain utopian, idealistic vision of the world before Marx, before the tragic alienation of the worker from work, from work tools, the results of work and from other workers. Or even an almost pre-Raphaelite retreat away from the cycle of mass production and consumption. (Could one - in honour of Sachs - create the term “pre-Marxist”?) Work, however, is the only thing that Sachs approaches without any kind of irony. One of the components of Space Program is the Indoctrination Station, where one can also watch a video made for the instruction of Sachs’ workshop assistants, in which the commandments of Sachs’ workshop are postulated. A voice offscreen formally announces: “Follow this guide carefully and you probably won’t be fired.”(28) /Translated into English: Filips Birzulis/ (1) Zinta Lundborg, "Tom Sachs lifts off for Mars propelled by booze, opium," Bloomberg Businessweek 2012. (2) Pasternak cited in: Emily Nathan, "Space Jam," Artnet, 15 May, 2012. (3) Katherine Satorius, "Tom Sachs," ArtUS, no. 21 (2008), 24. (4) Ariella Budick, "Tom Sachs: Space Program: Mars, Park Avenue Armory, New York," The Financial Times, 22 May, 2012. (5) Randy Kennedy, "From Earth to Mars, at the Armory," The New York Times, 9 May , 2012. (6) Kennedy, "From Earth to Mars, at the Armory." (7) Linda Yablonsky, "Man on a Mission," The New York Times Style Magazine, 17 May, 2012. (8) Sachs cited in: Lundborg, "Tom Sachs lifts off for Mars propelled by booze, opium." (9) Jon Kessler and Tom Sachs, "Tom Sachs," Bomb, No. 83 (2003), 71. (10) Sachs cited in: Nathan, "Space Jam." (11) Germano Celant, "Tom Sachs: the militarization of consumerism," in Tom Sachs, ed. Germano Celant (Milano: Fondazione Prada, 2006), 23. (12) Satorius, "Tom Sachs," 25. (13) Kennedy, "From Earth to Mars, at the Armory." “engage in intellectual, conceptual play” (14) Kennedy, ibid (15) Malcolm Gladwell, "Tom Sachs: everyday art," in Tom Sachs, ed. Germano Celant (Milano: Fondazione Prada, 2006), 31. (16) Celant, "Tom Sachs: the militarization of consumerism," 25. (17) The work was exhibited in the HUMAN + exhibition at Science Gallery in Dublin in the spring of 2011. More about this project – see www.julijonasurbonas.lt/p/euthanasia-coaster/ With thanks to Normunds Kozlovs for the reference to this work. (18) Celant and Sachs, "Tom Sachs - Germano Celant. Interview," 146. (19) See nikecraft.com/ (20) In the book John F. Love, McDonald's: behind the arches (New York: Bantam Books, 1995). (21) Gladwell, "Tom Sachs: everyday art," 33. “Kroc was concerned not with making fast food but with how fast food was made (. . .); he was an engineer, not a cook, and the Big Mac is what you get when you let engineers into the kitchen.” (22) Gladwell, ibid. (23) See: Anthony Gardner, "De-idealizing democracy: on Thomas Hirschhorn's postsocialist projects," ARTMargins 1, no. 1 (2012), 29-61. (24) Satorius, "Tom Sachs," 24. (25) Celant and Sachs, "Tom Sachs - Germano Celant. Interview," 43. (26) Gladwell, "Tom Sachs: everyday art," 35. (27) Gladwell, ibid. (28) An instructional film “Working to Code”, 2010, Dir. Van Neistat can be viewed on YouTube – www.youtube.com/watch?v=49p1JVLHUos | |

| go back | |