|

|

| Will Museums be Museums? Marita Batņa, Culture Theorist | |

|

New developments which have raised issues about museum ethics recently inspired debate in the art world. Last year, the New York galleries Haunch of Venison, Acquavella, and Gagosian held exhibitions which all had the common feature of being based on loans from American and European museums. The situation was described by Lindsey Pollock in ‘The Art Newspaper' (TAN), December 2008 issue, in the article titled "Public art for private gain?" Showing museum works in a commercial space could seem like a laudable occurrence, as it demonstrates the same standards and aspirations for galleries as for museums. In the context of traditional ethics, though, this equates to breaches of taboo such as putting pieces of private collections on sale shortly after being exhibited at a museum. At the root of the condemnation is the impression that the status of a museum is being exploited for commercial goals. So, has the art world outgrown its rules and there no longer is any particular difference between museums and the marketplace, because quality and prestige reign? The TAN debate was taken up by Michael Rush, director of the Rose Art Museum of Brandeis University (near Boston, Massachusetts, USA), who acknowledged a growing "synergy between galleries and museums", but concluded that museums should keep the market at bay. The Rose was among 22 "guilty" museums that helped Haunch of Venison (which is owned by Christie's) to secure an exhibition of Abstract Expressionism which was of tangible museum quality. The Rose's gem, Willem de Kooning's Untitled (1961) was loaned with the consideration that in New York it will be seen by more visitors than at its home over a whole year (paradoxically, the museum seeks to enhance its standing with the assistance of a commercial art institution). The course of events soon took a rather ironic turn: the museum managed by Rush had to face the harsh reality, the threat that the market may literally come in through its doors. In January, the university's board announced their decision to sell museum works - despite a promise not to include the entire collection in the sale, there is still the possibility of losing a lion's share of the value of the collection of 8 thousand pieces worth around 350 million US dollars. | |

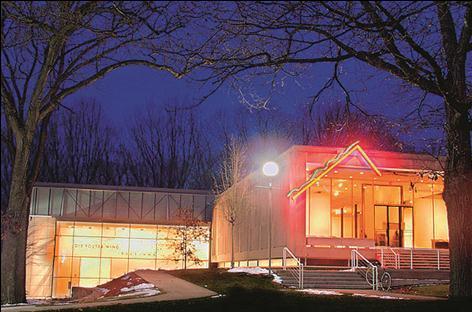

The Rose Art Museum of Brandeis University, USA | |

|

The Brandeis University museum is a rare victim of the economic crisis and this has been accompanied by fierce protests from stakeholders who aver that the heritage in public trust has been treated with disdain. The State of New York drafted a bill providing severe restrictions on the deaccessioning of items in public museum collections. In general, selling off museum works appears extraordinary, but is not that unusual - for example, the range of Sotheby's services for museums includes sales as well. The lesson of Brandeis University sheds light on the hidden flaws in the successful American model of museum supervision. During the recent market boom there was a shortage of museum directors, and as one of the reasons for this some anonymous comments were revealed (‘ARTnews', October 2008) about trustees overly interfering into management and focusing on income generation. Museum trustees are wealthy and prominent people, and many are active collectors; they are primarily charged to secure funds, however the area for decision-making is vast. An outstanding example is the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), for which Eli Broad constructed a new building to house his own collection, but the question is whether the museum was privileged or oppressed? When the Broad Contemporary Art Museum was opened (2008), it turned out that works would not be donated, but were to stay in the foundation managing loans to LACMA and other institutions. It is clear that ever more friendly relationships between museums and the art market have a fruitful context. The active and globalized art world is a challenge to museums, as the financial power lies in the art market part (something often not available to museums), and collectors establish new museums and galleries, thus increasing competition within the hierarchy of prestige. A shift towards the market in museum operations is more or less common practice with projects for maximizing attendance (for instance, blockbuster shows). Concern arises when this tendency approaches more extreme versions and museums seem to be turning into profit-making bodies. Loud voices have been raised against museum policies that focus on commercial gains and entertainment. Some time ago (when shows at the Guggenheim Museum and LACMA were the subject of debate), leaders of the Association of Art Museum Directors reacted through the publication of ‘Whose Muse?' (2004), a collection of essays where James Cuno reminded that museums are granted public trust to set values in an objective way, and this trust will be lost if their directors begin to sound like corporation CEO's. Despite the integration of museums into the market, either naturally or with scandal, the fundamental requirements expected from them cannot be changed. The collectors whose collections end up in museums expect that the assets will stay in safe hands for the next generations and will not return to the market. The art market, in its turn, needs to be quality-backed, that is by profound responsibility of museums (curators) for exhibitions and collections, supporting regeneration and selection processes in the market. Gallerists, curators and collectors regard museums, by their standing, the major background for the market, and there is no difference between public and private museums. Ideally, museum collections and activities are directed towards maintaining market stability and dynamics. For example, Robert Storr, the advocate of uncompromising curatorial standards, has noted that alert curators knowing a collection in depth, are trained to see, in the changing temper of times, what needs to be brought forward or recontextualized and are charged to make decisions accordingly. The art world is said to be the least regulated and least transparent of all sectors. Museums, collectors, patrons, gallerists, dealers and politicians network to each other's benefit; conflict of interest is almost irrelevant. However, the mission-based independence of museums in their dealings with outside forces remains of high ethical sensitivity, because the cultural heritage and a fair attitude to it are the subject. | |

| go back | |