|

|

| XXX Rihards Pētersons, art historian

Irēna Bākule, Arnis Siksna. Riga Beyond the Walls (Rīga: Neputns, 2009)

| |

Irēna Bākule, Arnis Siksna. Riga Beyond the Walls. pp.: 56-57 | |

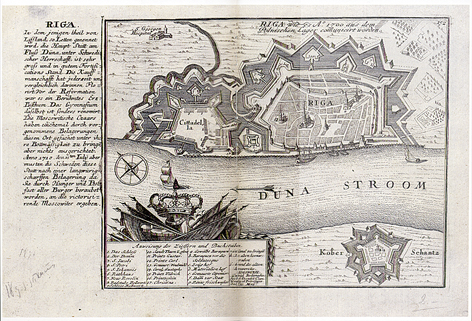

| Historic cartographic materials have vast potential as a source of reference. Publishing a compilation of maps provides professionals, as well as the public at large, with a good foundation for deepening their understanding of not only the historical, but also the contemporary context. This holds true in reference to a publication by the Neputns publishing house - a joint work by two authors: architect Irēna Bākule (Latvia) and urban planning specialist Arnis Siksna (Australia). Both authors draw on the cartographic materials of the Riga fortification walls and the adjacent areas to tell the history of Riga city planning in the area. Despite the reduced scale of the maps (to conform to the size of the book), the printing quality is excellent, and the majority of the maps can be studied in detail by anyone who should wish to do so. The majority of the maps come from the collections of the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation, and some have been used in research by other authors. However, the book by Irēna Bākule and Arnis Siksna gathers together the maps in a systematic way to give a reasonably clear idea about the spatial development of the suburbs. In the 17th century building work beyond the Riga fortification walls was granted legal status, and was carried out not only next to the main roads, but also began to spread further. Radical changes with regard to city planning were introduced by a new approach to the function of the Riga fortress. If in the second half of the 18th century an esplanade was created - a building-free vacant area in the close environs of the Riga fortress - then in the early 19th century the development of the suburbs was determined by their division into five regions, which significantly influenced the character of the construction work. The demolition of the fortification walls in the mid-19th century and the creation of a ring of boulevards played a crucial role in the formation of the present day urban landscape of the historic centre of Riga. Furthermore, the functional zoning created at that time is still applicable to 21st century Riga. Whilst the attractive and for that time visionary proposal by architect Johann Daniel Felsko to build a closed shopping arcade along the waterfront of the River Daugava was not realized, then that idea was brilliantly implemented during Latvia's first period of independence by erecting five zeppelin hangars in the area that had been designated for trade and market activities earlier. The 19th century city plans already highlight the necessity of bringing together the territories of the two suburbs into a united urban structure; however to this day this idea has not been implemented. On the contrary, the construction of large-scale buildings along the railway, for example the Stockmann centre, could make this process irreversible. The problem is in the functional, and even more so, the visual isolation, since the visual aspect is considered just as important as functionality in terms of the quality of the urban environment in modern city planning. | |

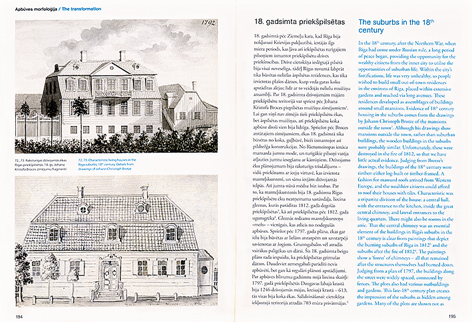

Irēna Bākule, Arnis Siksna. Riga Beyond the Walls. pp.: 194-195 | |

| Bākule and Siksna also discuss a less well-known design proposal by Felsko. The Lielā Smilšu Road (presently the continuation of Brīvības Street in a westerly direction, towards Old Riga), was the "backbone" of the reconstruction project of the Riga ramparts and esplanade, where the said road would be transformed into a boulevard, with a large circular central plaza in the former esplanade area. The plaza wasn't built; however, the idea to bring the two hitherto separate parts of the city together into a united and grand structure was implemented in a brilliant manner. The monument to Peter the Great and the subsequent construction of the Brīvības piemineklis (Freedom Monument) confirmed that, besides being functional, the Brīvības Boulevard in Riga is also appropriate for ideological expression. Hence it is not coincidental that in the 1930s the architect Ernests Štālbergs proposed that a circular plaza, enclosed by a wall, should be built around the foot of the monument in order to enhance the spatial structure visually, however, this design was not carried out. It is worth pointing out that still today, those who work on detailed planning of the Riga Town Hall Square, the memorial to the victims of Soviet occupation in Strēlnieku laukums and the concept for the utilization of the Uzvaras parks in Pārdaugava - have repeatedly emphasized the idea of an east-west axis and its spatially orientating role, thus continuing mid-19th century town planning concepts and adapting them to urban planning requirements of the current century. In presenting their view of the 300 year history of urban planning in Riga, the co-authors have sought to draw parallels with similar processes abroad and to substantiate the assumption that Riga is a city belonging to the Western European traditions of culture and town planning. Besides, the stylistic expressions of various ages, such as Renaissance, Baroque, Classicism, Eclecticism and Art Nouveau, which usually characterize buildings and architectural ensembles, are, with good reason, transferred by the authors to describe spatial structures. It is evident that both authors are keen to distance themselves from any information that might distract the reader from looking at the work as a study of town planning. Only lightly sketched in, and even then as if in passing, the authors make reference to a few owners of the land in the suburbs and on the boulevard ring, as well as the individuals who financed development and put to good use the expansion of these territories, as well as the architects who designed the numerous buildings. These aspects are left to be explored by other researchers. This work, however, gives a clear picture of the peculiarities of the present-day street grid in Riga's historic centre, explains the historical aspects of the building plot configurations, gives the reasons for the diversity of inner city block planning, makes clear the presence of low-rise wooden buildings in the so-called capitalist Riga, etc. If much of the information included in this book may already be more or less known to an observant reader who is familiar with the professional field, then the parallel text in the English language is a particular bonus. Conceptually this is no different from the Latvian original, but in places where a direct translation would be a little more difficult to understand for a foreign reader it provides clarifying details. Finally, mention must be made of the production quality of the book as a printed work. The visual quality of the maps is good - the maps are presented in their authentic condition, as historical documents. The binding of the pages is of good quality, as the larger maps are printed on double-page spreads, and the binding holds even after the pages are opened to their maximum extent. The choice to print this edition as a paperback is slightly unorthodox for a book requiring high printing quality. To the reviewer this is vaguely reminiscent of Soviet era notebooks, which were widely used by students to compile their class notes and were used for a long time after graduation for references needed in their professional work, the notebooks retaining their physical durability throughout. Possible another advantage of this kind of edition lies in its affordability, which may entice potential buyers in bookstores to pick the book up and take a closer look, to investigate both the contents as well as the price. /Translator into English: Vita Limanoviča/ | |

| go back | |