|

|

| Already then, already then... Jānis Borgs, Art Critic Artist Leo Preiss (1946) | |

| In the consciousness of today’s generations in latvia the distant 1960s quite often are mistily perceived as the period of soviet oppression. cultural life at the time took place only according to the dictates of red ideology. the sun hardly shone, the birds didn’t sing... that’s a kind of half-truth, however. it should also be remembered that after the stalinist “winter”, the “spring” of khrushchev arrived with, for those times, long unseen semblances of freedom. they burst forth after the ussr cP xx congress which took place in 1956 with the unmasking of the cult of personality and a general loosening of the regime’s customarily tight grip. the Party “solemnly declared” the imminent arrival of communism (already by 1980), and the sunny mirage was already beaming over the horizon. in the minds of many people, the enthusiastic hope for a brighter future was riding the crest of a wave, even if later it turned out to be a rather naïve hope. the younger generation of the so-called creative intelligentsia quite nimbly leapt over the hurdles of the enclosure of orthodox social-realism, raised over many long years by party decrees, and spread out widely across the pastures of modernist ideas, where the fresh air flowed in mainly from a westerly direction. a tide of all kinds of free thinking and “formalistic” art caught unprepared the bosses of the only, but nevertheless omnipotent and also “our beloved” party, and gave them a real fright. In 1963, this fear transformed into a mighty and paranoid allunion anti-formalist campaign which was generously supplemented by a thorough ideological grooming of the intelligentsia and not entirely successful attempts to herd the “straying sheep” back into the pens of the culture-farms nurtured by the party. once again, fiery sermons and reminders about the inviolability of the ideologically sacred red line were to be heard. in his 1963 speech, leonid fyodorovich ilychev, the kremlin’s chief ideologue of the time who had been elevated to the rank of philosopher and academic, pointed out: “literature and art cannot develop in our land without a rudder and sails.” it’s not hard to imagine who were the helmsmen and who was putting wind into the sails. of course, the communist Party’s grand barons sitting on moscow’s olympus. then this helmsman announced: “our art has the great fortune that the party which voices the primary interests of the people (..) determines the artistic tasks and direction of creative work. (..) the main line of development in literature and art was prescribed in our party programme. (..) the peaceful co-existence of socialist and bourgeois ideology has never existed and cannot exist.” here it should be explained that the concept of the “peaceful co-existence of two systems” in the poststalinist soviet union actually arose in the sway of the suicidal nature of the potential atomic war. that cooled things down considerably. but not ideologically. | |

Leo Preiss. 2014 | |

| that’s what once was the rather tragicomic background to 1960s social life throughout the sovietland, against which, however, quite unexpectedly diverse cultural processes took place not really as “correct” as the various communist Party capos would have wished. Quite the opposite – the genie, once released from the ideological bottle, couldn’t be put back in again. because the old methods of physical terror were now put on the backburner, and to incur the reigning power’s relatively mild, though no less nervous repressions, one had to make a really special effort with openly subversive defiance. writers, poets, theatre or cinema folk were able to achieve this occasionally, but the dissidents of visual art less so, as their working methods apparently seemed much less dangerous, in terms of influence on people, than the power of the word or of ideas. the “leading party’s” incited clash with the creative intelligentsia led to a polarization in official and nonconformist art which in some places, mainly in russia’s big cities, could have already been deemed “underground”. in the 1960s– 70s, the powers-that-be still tried to “redirect” the formalists towards non-ideological fields – for example, into design, the applied arts and architecture. many also agreed to be called designers because this didn’t change alternative aesthetic expressions very much, but did legalize a certain freedom of artistic form. from the perspective of the ruling power, in this way the allegedly mercantile or neutrally decorative essence of these branches was accented, as opposed to the noble flight of “pure art” in the clouds of the socialist ideal. a significant example here is the overreaction which took place in 1972 in connection with the opening of the famous modernist exhibition at the former riga bourse. in the soviet latvian era this was the first major public appearance of art of this kind and also a challenge which the powers-that-be condoned, but solely as an exposition of “design only”, in addition they required its ideologization in the form of a reverential dedication in honour of some anniversary or congress. and the process began to move ever faster. both modernist “designers”, as well as “pure” non-conformist artists multiplied in numbers that the ruling powers found rather unpleasant. in recent decades our art historians and curators have quite generously illuminated this period through various exhibitions, research, new discoveries, and in publications as well. in this context, up until now the presence of a quiet and unambitious artist had, perhaps undeservedly, remained unnoticed, but the radical art scene of the soviet latvian period would seem incomplete without some attention being focused on him. his name is Leo Preiss, the father of geometric painter Henrijs Preiss who now lives in the west and has recently shot to prominence with us. it seems that one can find a certain inherited creative principle here, as at one time leo also developed his art specifically in the area of geometrical abstractionism. even at a time when it wasn’t really allowed, or when it wasn’t officially considered to be acceptable – in the soviet 1960s–80s. it should be added that what was forbidden was in many ways dependent on the “label” attached to it. for example, an abstract composition could be declared to be décor, or an article of applied art, and not art, and was thus considered good and progressive. we can find the line of inheritance mentioned even deeper, symbolically – in the life of leo’s father, kārlis Preiss, a man of letters and a teacher. much of his life was spent in soviet russia, both in the exuberant times of the proletkult, when the russian avant-garde culture with its superstars malevich, klucis, rodchenko, tatlin, lissitzky and mayakovsky thrived, as well as in the maelstrom of the great terror of the 1930s, when the word латыш (latvian – ed.) meant the death sentence for thousands. kārlis Preiss was lucky to survive, finding refuge in the “backwoods” of the caucasus, and finally arriving back in latvia only after the second world war. his son leo, without a doubt, gained valuable knowledge from his father about the sharko shower-like cultural life in red russia. in any case the artist himself emphasizes how important and influential the exploration of the russian avantgarde was for him. in the 1960s it had not yet completely lost the stamp of being “formalist” and “bourgeois” that was imposed on it during the years of stalin’s reign, even though the artists themselves, once denounced as “enemies of the people”, had long ago been rehabilitated. but many of the art publications and magazines of the ussr and socialist countries were already broadly and brazenly announcing this as the origin of soviet design. only after this russian avant-garde was lauded and widely feted in western countries, it is true. and so, in the late 1960s, a quiet student blessed with gentlemanly charm – Leo Preiss, turned up at the department of in- terior and furnishings of the latvian academy of art. his polished aryan exterior didn’t indicate anything revolutionary, and even less so, anything of the proletkult. the young aspirant’s interest outside his field of study was characterized by a somewhat fiery radical’s obsession with the transfer of constructivism and geo- metric art into painting. there was no way that these kinds of things could fit in directly with the study programme. modernism and its ideas were still, if not quite taboo, then at least terra incog- nita, even though there was no shortage of formal exercises simi- lar to those in the design departments behind which definitely stood the compositional exercises and principles of bauhaus, as well as russia’s VKHUTeMaS. it was all there. in this hypocritical situation, the declarative bolshevism of the russian avant-garde artists in the 1920s was most useful as a powerful and tactical argument of defence. mentioning this at times helped, like a bulldozer, to push aside the ideological objections and tantrums of the censor, that this kind of art was foreign and unacceptable to the soviet man. who could be a more noble “example of a soviet person” than, for example, Latvian red rifleman and fiery bolshevik, one of lenin’s own guards, gustavs klucis (even though in the end he was to be shot for being a “Japanese spy”). | |

Leo Preiss. Cathedral. Tempera on canvas. 64x46 cm. 1967 Publicity photo. Courtesy of the artist | |

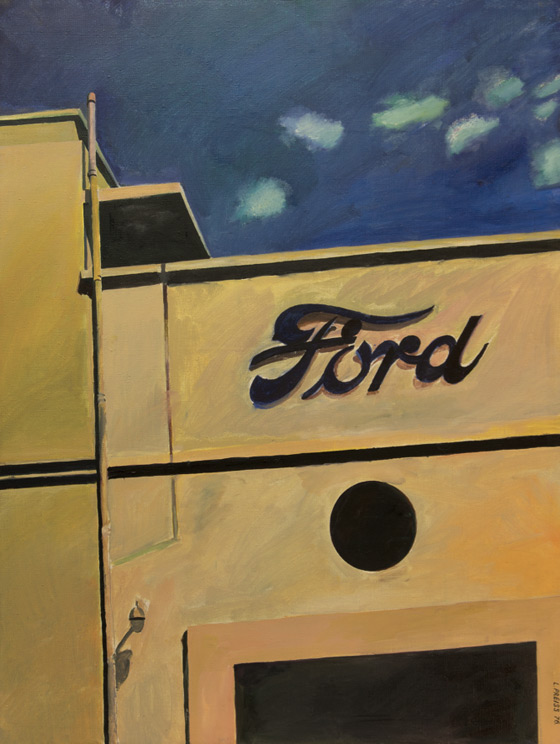

| a range of leo Preiss’ paintings from that time provide evidence of his fervour for the cubo-futurist avant-garde of the 1910s-20s and its aesthetic. in one early work, riga’s orthodox nativity of christ cathedral is depicted. at that time, in the euphoria of one of the state’s regular atheistic fits, it had been vandalized and transformed into the house of science and Planetarium. this was presented as a victory of “enlightenment” over religious obscurantism. in the complex there was also an exhibition hall, in which exhibitions of non-conformist art took place more frequently than anywhere else, thereby earning fame as a creative experimentation ground. this was a kind of zone of special leniency and benevolence on the part of the censorship, as the “organs of control” searched mainly for any flies in “the contents” of the ointment in art expositions taking place here, but didn’t usually pick a fight on questions of form. this made the young artists and their admiring public altogether happy, but the adjacent bar and café known as Dieva auss [god’s ear] - even more so. Preiss painted this neo-byzantine architectural object without any contents-based allusions to the site’s “expressive” social contexts, merely musing over its many round parts in a kind of cubist manner. the appearance of the painting brings to mind robert and sonia delaunay’s orphism. and the language of its form, in a way, programmatically marked the next development in geometric minimalist painting. at that time, one could find out a lot about cubism, futurism, dadaism, art deco and the aesthetics of other movements by making a visit, for example, to the apartment of taņa suta and aleksandra beļcova, where it was possible lounge around in an oasis of pre-war latvian and western european modernism. on rare occasions some of the academy’s lecturers in art history also organized visits for their students to the museum’s semi-secret closed collections. there, with bated breath, one could view the “bourgeois decadence” from the nation’s first period of independence, namely, masterpieces of latvian expressionism and cubism. for leo and a small group of his fellow students, this era of various “isms” was of continuing interest and the most popular topic of discussion. the academy of art also provided a small, but wonderful opportunity for “letting off steam” for “experimental” art practitioners. at the end of the 1960s, independent exhibitions of students’ works were in favour there, and this is where for the first time works by leo Preiss appeared as well. at these exhibitions the contradictions between the fairly conservative teaching programme and the honest attempts of some art students to grow the forbidden fruit of the modernist concept in home conditions were unpleasantly revealed. Participation in these exhibitions was open to anyone who was interested, without restriction. but due to their scandalous nature, they were closed and meant for “internal use” only. the person on the street was not allowed inside, and the ordinary soviet citizen didn’t have any idea of the type of heresies that were germinating within the lofty walls of the neo-gothic building. clearly, the powers-that-be and all sorts of “organs” knew about the modernist “trick” taking place here, but the academy could easily argue that what was taking place was a kind of educative prophylactic, as one could find out a student’s true thoughts in this way, and these could be then professionally talked over and more easily directed onto a path “more desirable for us”. alongside the art influences already mentioned, powerful formal impressions from “pop”, or american or british Pop art, also appear in paintings by leo Preiss. as a particularly influential innovation from western culture this left an imprint on the minds of many young artists in soviet latvia in the 1960s–70s. leo, too, as if joined this significant mainstream. some of his paintings featured photographic fragments from the street environment in close-up. a street sign, a bit of a ford advertisement... nothing there provided evidence of belonging to the local urban situation. an entirely cosmopolitan generalization. and additionally a series of works where the subject motifs of Pop art were arranged in decorative geometricized compositions. in many ways the raw polychromes and the “cheery” colour code of Pop art became a principal characteristic in Preiss’ paintings. overall, the combinations of colours in his works didn’t have anything at all of what we understand with the concept ‘latvian’. and there’s no doubt that that defenders of this principle, and the purists of latvian painting, could have been seriously upset by his activities in art. here we must concede the somewhat imitative tendency of local or regional pop art and its detachment from the primary, original social motivation of this trend which was born in the west within the reality of a capitalist consumer society. in sovietland such a society was only just beginning to develop. it was during the 18 years of brezhnev (brezhnev was the USSR CP general secretary and led the ussr from 1964 – 1982) that the soviet person was given the opportunity to enjoy the taste of material goods, although the goods were usually not retailed in a normal way but rather “thrown” into the market, like food to piglets at feeding times. cravings and greed were promoted by the endless shortages of all types of goodies, and voracious hunting instincts were sharpened by the all-pervasive system of “knowing the right people”. later, in the perestroika period, it seems that this “culture” truly motivated the development of soviet pop art into soc-art (a social-realism parodying hybrid). but that was later and did not apply to leo Preiss in any way. | |

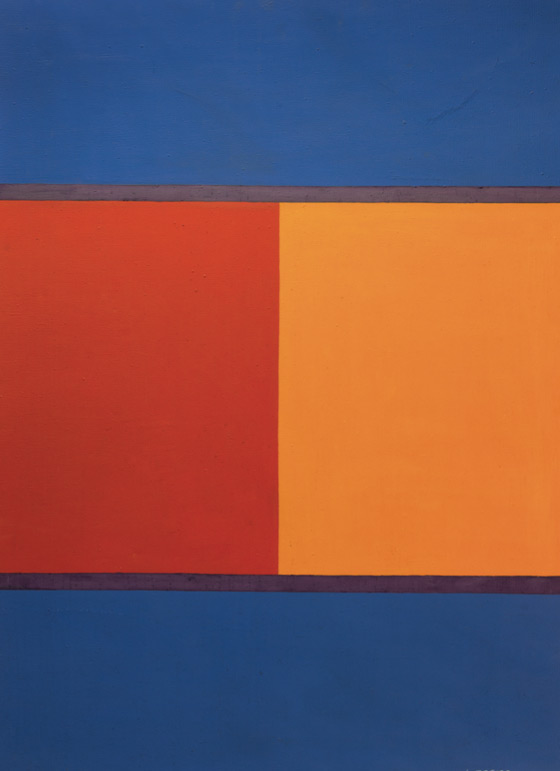

Leo Preiss. Composition 823. Wax, oil on canvas. 100x73 cm. 1982 Publicity photo. Courtesy of the artist | |

| The 1960s modernist practices in the art processes of the soviet era do reveal, however, how rusted through the iron curtain was, and the scale on which a variety of western influences flowed in, despite the apparently hermetic isolation and filters of censorship. the main sources of information were the art periodicals and books from the “brotherly” socialist countries, as well as art publications from western countries, which got through mainly by post. more rarely there were various exhibitions of art, design and other achievements from western countries in the large cities of the ussr, as were specialized library sources and radio, too, and when visiting tallinn - finnish television. information was of huge value and it also had a taste which can only be savoured by the hungry. this kind of “mediaeval” tundra diet was the complete opposite to today’s tsunami waves of information. no internet, no global television, no mobile telephones and satellite communication, nor the world press and mountains of books, no mass travel outside the “mighty and vast homeland”... it was another planet. or “our common encampment”. Leo Preiss was able to condense the hive of various impressions fairly quickly into minimalist line and field paintings. the “striped mattress” canvases also appeared, with similar ones seen in various western prototypes, for example, in the captivating works by american frank stella. gradually this trend also progressed to geometric three-dimensional compositions, developing ever more original, and more complex compositional solutions. initially, the artist consistently developed his paintings mostly on a plane, but in his later development there were geometrical compositions with three dimensional objects and spatiality as well. for a while the artist drew inspiration for his geometrical shapes from intensive research into the forms of crystals. he found the magic of their exactness not just in specialized literature, but also, and especially, from visiting the academy of sciences’ mineralogy museum in moscow. there, in the grand empirestyle hall, was a huge collection of crystals stored in old-fashioned glass cases. and leo, so it seems, was the only visitor there who was looking at these scientific exhibits through the eyes of an artist. in fact, a creative personality could have quite easily built their entire artistic life on these nature-given material foundations. But in this respect leo’s life did not move forwards so smoothly and briskly. his activity in geometrical painting, which had started so promisingly, gradually stalled. a reason for this was the not very favourable organizational climate of local art. you wouldn’t say that he’d been somehow specially tormented by the censor, as the latter in fact lacked any “material to chew on” – just simple “formalism”. this could also be interpreted as an asocial phenomenon, evading reflections on the “sunny reality”, internal emigration... in actual fact it wasn’t just the ruling power, but also the “ordinary folk” and “public opinion” who didn’t take these works by leo seriously. how can this be art – all sorts of lines and little cubes?! well, in the best case it’s a kind of décor for, let’s say, a kindergarten... it should be added that “line art” in the form of large supergraphic paintings appeared in a string of public interiors at the end of the 1960s and into the 70s. supergraphics, another idea which had come in from the west, adapted well enough to the soviet environment as “decorative art” or “interior design”. its complete ideological innocuousness, optimistic joyfulness of colour, movement, clarity and positivism didn’t provoke problems and satisfied just about everybody. however, leo did not consider his works to be decor, and this already made the situation difficult. the “craft guild” barriers, too, turned out to be more serious, as here you could no longer blame the powers-that-be and ideologues. a strictly defined professional “pecking order” system was in existence, in which one’s territory was always jealously defended. from the point of view of “licenced” and educated painters, leo was some sort of “little interior designer”, some “upstart” who’d wandered in from nowhere and an outsider who had no business in the professional mileu of painters. that, of course, had a significant impact on opportunities for participating in large art exhibitions with the kinds of works offered by Preiss. the works that he submitted were simply not accepted there. the only exception being participation in the previously mentioned 1972 exhibition at the bourse. but participants there were regarded as designers, at least officially. and then there was participation in the exhibitions of the annual art days of latvian artists union, which were liberal and free of censorship. otherwise he had to reconcile himself to a few rare expositions in marginal exhibitions in the provinces and in second-rung shows in riga. throughout the soviet period, Preiss had only a few small solo exhibitions: at the daugavpils museum of local history and art, as well as at the, then famous, popular shop art Books in Daile house where the osīriss café and a décor shop are now located. More than one young artist of that time, having set out on the path of avant-garde art and not having received immediate recognition, took it dramatically, sinking into depression, and even terminated their creative activities. we could call this a lack of belief in one’s vocation, an absence of confidence, a nihilist attitude to future opportunities and development. to an extent, something similar also happened to leo Preiss, but he was still able to turn potentially destructive processes into a rationally productive conveyer. his spouse ingrīda Preiss was an artist in the field of leatherwork. and so now leo focussed his creative energy and the principles he’d developed in painting on decorative compositions for the leather covers of various books and diplomas. the artist consoled himself that nothing from his geometric art concepts would be lost in this way. but along with the substantial profits, he also felt needed and recognized by the public. leo himself considers that the refuge he found in this way gave him a great feeling of comfort, and he has no intention of grumbling about his creative fate during the soviet period. Be that as it may, this aspect of leo Preiss’ activities in applied art should be studied in some completely different research project. yet thinking about his soviet period painting, it has to be admitted, with certain regret, that it didn’t gain the appropriate exposure and develop further. at that time, the author painted about 30 works in total. their main value, it seems, is the confirmation of alternative and contemporary artistic thinking, despite the conservative soviet cultural environment still dominating at the time. that is to say – winter was not yet over, but the early starlings had already arrived. some froze to death. but leo Preiss’ painterly achievements should be noted as a bright accent on the landscape of latvian art of the time. | |

Leo Preiss. Alexandria. Oil on canvas. 100x73 cm. 1976 Publicity photo. Courtesy of the artist | |

| Translator into English: Uldis Brūns | |

| go back | |