|

|

| What's next after the year of the selfie Alise Tīfentāle, Art historian or work in progrees by Lev Manovich and the software studies initiative | |

| “I thought I understood, but now I am not sure anymore...” Lev Manovich during a vigorous team discussion on Basecamp.com in December, 2013 This is not about doubt or confusion. this is just a brief moment in a longer research process where leading scholars and experts work towards discovering something. for me, this quote perfectly describes a feeling that i have been having almost every day since last fall, when i started working as a research assistant to one of these leading scholars, namely, the legendary lev manovich. he is professor of digital humanities and computer science at the graduate center of the city university of new york and founder and director of the software studies initiative at the california institute for telecommunications and information technology (calit2) and the graduate center. in 2013 he appeared as second on the list of 25 People Shaping the future of Design.1 in July 2013 lev manovich published Software Takes Command, a groundbreaking contribution to the growing field of software studies and the more general area of digital humanities.2 This article will provide a brief insight into the book and some of the most recent projects conducted by manovich, and will also outline a completely new research project we are working on right now (as of 6 January, 2014). as the new project is scheduled to be launched at the same time this issue of the magazine is due to be published, readers are welcome to follow updates about it and related activities and publications on the websites www.manovich.net and lab.softwarestudies. com, as well as by following manovich on twitter and facebook. Who’s Afraid of Softwarization Software Takes Command explores the recent developments of software for media creation and editing, and among many other advanced topics manovich discusses topics like media software, metamedia, computational media hybrids, media gestalts, and software epistemology. as manovich has claimed, he was the first to use the terms ‘software studies’ and ‘software theory’ in 2001.3 software, the subject of the book, can be viewed as the seemingly invisible engine that makes the world run. first, there is the visible part or the user’s interface, such as all these more or less nicely designed websites with their “like” and “share” buttons to push, boxes to fill with our comments, and easy to manage shopping baskets. and then there is the invisible software, the actual algorithms that make all of this possible and effective. the book explores how these algorithms influence human perception and behavior. Terms such as ‘new media’ and ‘digital media’ are often used and easily applied (also in the context of art) to anything that has to do with computers and/or internet. however, it turns out that these terms are way too superficial and do not reflect the actual complexity of matters, according to manovich. he argues that “there is no such thing as digital media.” there is only software – as applied to media (or “content”).”4 furthermore, that which we might call media “becomes software.”5 he also revisits the term ‘new media,’ pointing out that “software-based media will always be “new” as long as new techniques continue to be invented and added to those that already exist.”6 one of the main points manovich is making in Software Takes Command derives from the assertion that “the computer is not a new “medium” – it is the first “metamedium”: a combination of existing, new, and yet to be invented media. (...) softwarization virtualizes already existing techniques and adds many new ones. all these techniques together form the “computer metamedium.””7 to explain softwarization, manovich introduces concepts such as media hybrids and media gestalts: “media hybrids, interfaces, techniques, and ultimately the most fundamental assumptions of different media forms and traditions, are brought together resulting in new media gestalts.”8 overall, manovich argues for the shift of emphasis from the idea of medium to the understanding of software and its role in shaping any kind of media production: “this (...) is the essence of the new stage of computer metamedium development. the unique properties and techniques of different media have become software elements that can be combined together in previously impossible ways.”9 | |

Lev Manovich. 2013 Publicity photo Courtesy of the Calit2 | |

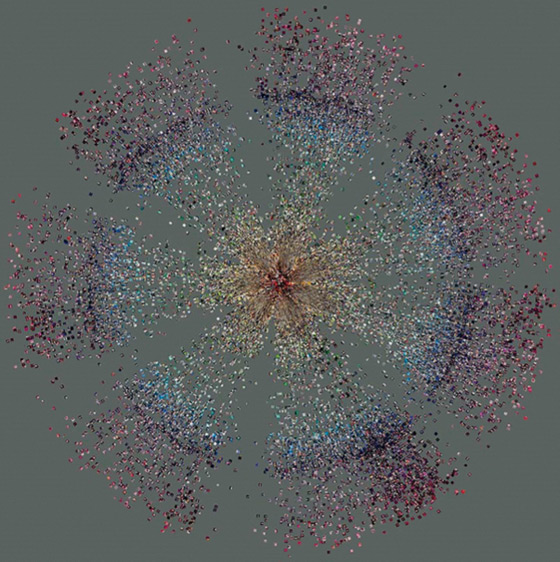

| ‘Metamedium’ in this context can be viewed as a metaphorical ecosystem, an all-encompassing environment that determines the functioning of each element. according to manovich, “the functional elements of social and mobile media – search, rating, wall posting, subscription, text messaging, instant messaging, email, voice calling, video calling etc. – form their own media ecosystem. like the ecosystem of techniques for media creating, editing, and navigation realized in professional media software during the 1990s, this new ecosystem enables further interactions of its elements.”10 even though a description of such an ecosystem that includes practically anything we do might well sound like another big brother story, manovich in this book is more analytical than sceptical or critical. his arguments do not convey any complaints or fears that we might find ourselves trapped in some sort of dystopian surveillance network and become slaves of obscure algorithms written by a bunch of powergreedy nerds from silicon Valley. that is the job of fiction writers like dave eggers who does exactly that in his latest novel The Circle, classified as a technothriller according to amazon.com.11 egger’s circle, most likely a metaphor for google, is a giant panopticon where everyone’s online and offline behaviour is being watched for the sake of common good and, of course, in the interests of capital. in a less techno-thrilling but completely scholarly and distanced manner manovich concludes that “following the first stage of the computer metamedium invention, we enter the next stage of media “hybridity” and “deep remixability.” (...) this condition is not a simple consequence of the universal digital code used for all media types. instead, it is the result of the gradual development of interoperability of technologies including standard media file formats, import/export functions in applications, and network protocols.”12 open access edition of the book is available online and for free – follow the link on manovich’s website.13 The World As Seen by the Aggregate eye Theories and concepts discussed by manovich in Software Takes Command are closely linked to actual research conducted by him and the software studies initiative team. one of the major research projects is Phototrails, an innovative project that hybridizes approaches and methods from diverse fields such as computer science, media studies, sociology, and visual art. the methods, software, and results of the research are constantly updated and available online at phototrails.net. the subject of the research is related to the visual culture, social media, and contemporary vernacular photography: a gigantic database of photographs uploaded by users to the internet and shared via the smartphone app instagram which was launched in 2010. thousands and millions of photographs in this case are not viewed or interpreted individually, but rather treated as data, an approach that belongs to the new and exciting field of big data as well as the emerging concept of cultural analytics. the research questions of the project are related to an analysis of the photographs aimed at making sense of this seemingly endless flow of images: how to read this kind of big data, and what can we learn about a particular city or a particular moment in time from these photographs. the significance of social media also cannot be underestimated. manovich likes to emphasize the role of twitter, facebook, linkedin and the like, constantly reminding us about the different ways how academia, including art historians and theorists, can benefit professionally from smart use of these social media. if you don’t tweet, you don’t exist. it’s not that an impressive online presence will guarantee someone a dream job, he said in a private conversation, but it is relevant in terms of professional networking, which is a key when it comes to learning about freshly open vacancies, new research initiatives, collaboration projects inside and outside academia, and so on. The methods used in the project are borrowed from sociology and statistics as well as from the field of computer science, which, among other tools, include custom-made software written by manovich. to complicate matters even further, the results of the research are presented in a visually stunning form that can be viewed as examples of infographics or data visualization, a new and extremely fashionable branch of design, or even works of art. according to the Phototrails team, it is a “research project that uses experimental media visualization techniques for exploring visual patterns, dynamics and structures of planetary-scale user-generated shared photos. using a sample of 2.3 million instagram photos from 13 cities around the world, we show how temporal changes in the number of shared photos, their locations, and visual characteristics can uncover social, cultural and political insights about people’s activity around the world. the project is part of the emerging research field of cultural analytics that uses computational methods for the analysis of massive cultural datasets and flows.”14 In Phototrails, individual images become data. each user’s personality, artistic (or other) intentions, and the content of the actual image are not relevant. the images in this project are sorted according to their geographical location and time stamp (which is automatically added to all images posted on instagram), as well as several formal qualities that can be measured and compared automatically by software - such as brightness median and hue median. it is a giant pool of digital data and metadata that can be analyzed using both standard and custom-made statistics tools that show, for instance, how 50 000 instagram photographs taken in the same time period in tokyo and bangkok differ in terms of brightness mean and hue mean. or how a database of 23 581 photographs taken in brooklyn during hurricane sandy (29–30 october, 2012) reflects the impact of the power outage. Of course, there are some socioeconomic limits to the whole project, as data (that is, image) production in this case is limited to users of smartphones who are active users of instagram. even though it may seem that it’s about everyone in the world, actually it is a relatively small fraction of the population. the un international telecommunications union predicted that “there will be around 6.8 billion mobile subscriptions by the end of the year,” considering the current world population of approximately 7.1 billion.15 the number of smartphones is significantly lower. Business insider recently claimed that by the end of 2013 there would have been 1.4 billion smartphones.16 the number of instagram users is even smaller. the app for sharing photographs and short videos allegedly had more than 150 million monthly users in september 2013.17 it is just speculation, but it is very likely that the smartphone users who also actively post on instagram are mostly urban, young, and with a certain level of income that supports the purchase of the device and monthly expenses related to network subscription and service fees. then one may ask, why instagram? manovich and nadav hochman have emphasized the following: “our work takes advantage of the particular characteristics of instagram’s software. instagram automatically adds geospatial coordinates and time stamps to all photos taken within the application. all photos have the same square format and resolution (612x612 pixels). users apply instagram filters to large proportion of photos that give them an overall defined and standardized appearance.”18 in addition, the whole phenomenon of instagram is a perfect example of softwarization that manovich discusses in Software Takes Command: “the new “global aesthetics” celebrates media hybridity and uses it to engineer emotional reactions, drive narratives, and shape user experiences.”19 describing the methods employed in the Phototrails project, manovich and hochman have pointed out that it “integrates methods from social computing, digital humanities, and software studies to analyze visual social media. (...) using large sets of instagram photos for our case study, we show how visual social media can be analyzed at multiple spatial and temporal scales. (...) we introduce new visualization techniques which can show tens of thousands of individual images sorted by their metadata or algorithmically extracted visual features.”20 Results of this research have been presented as works of art – large scale prints and video – in an art gallery context. The aggregate eye: 13 cities / 312,694 people / 2,353,017 photos by nadav hochman, lev manovich, and Jay chow, co-curated by alise tifentale and hyewon yi , was on view at the amelie a. wallace gallery in old westbury, new york (29 october – 5 december, 2013).21 the exhibition opened with a lecture by manovich “from atget to instagram: representing the city.” among other topics touched upon in the lecture, manovich raised the following concern: “maps, photographs, and cinema are the principal technologies that individuals, small groups, and businesses traditionally have used to represent cities. today, urban representations can be created by hundreds of millions of ordinary people who capture and share photos on social networks. if we were to aggregate these masses of photos, how would our cities look? how unique are the photos captured by each of us? are there dominant themes regardless of location?” thus the results of a hybrid sociological/media studies/computer science/big data research project entered the white cube, the elevated realm of fine art. Interestingly enough, reviewers of the exhibition focused mostly on the aspects of social photography and social media that The aggregate eye mobilized, but seemed to ignore the potential new aesthetics that big data visualization brings into the art world. for instance, Paul longo in Musee Magazine noted that the exhibition “turns a spotlight onto the world of social photography, raising a whole new generation of questions concerning art and its place in society.”22 similarly, dale eisinger in Complex stated: “a genius new exhibition... examines the patterns created by our ever-increasing output onto social media.”23 The aggregate eye definitely is not a singular exception in the context of the art gallery circuit. for instance, almost simultaneously, artist and software engineer casey reas launched his latest exhibition Ultraconcentrated at bitforms gallery in new york.24 one would not dare to start talking about reas’s work using scholarly art history language, as discussions about aesthetics, meaning, and formal qualities such as composition or materiality of art do not seem to be appropriate to what is being called “generative software art.”25 at the same time, his artistic practice is very much linked to all the more traditional and widely accepted art forms, with the difference that reas “writes software to explore conditional systems as art. through defining emergent networks and layered instructions, he has defined a unique area of visual experience that builds upon concrete art, conceptual art, experimental animation, and drawing. while dynamic, generative software remains his core medium, works in variable media including prints, objects, installations, and performances materialize from his visual systems.”26 it could be argued that reas’s works, just like The aggregate eye, explore the artistic possibilities of media hybridization and computational metamedia that manovich analyzes in Software Takes Command. in order to make sense of such artworks in the context of visual art, and to describe and discuss it adequately, a new and equally hybridized art critical vocabulary might be needed. big data and software can be beautiful and meaningful, but art critics do not seem to have the appropriate critical apparatus to approach it. The Mystery of the Selfie and How to Make Sense of It the current research project in progress led by lev manovich is focusing on selfies posted on instagram. a selfie, according to the oxford english dictionary, is “a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.”27 on 19 november, 2013, oxford dictionaries announced ‘selfie’ as word of the year 2013. the oxford dictionaries word of the year is a word or expression that has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date. language research conducted by oed editors reveals that the frequency of the word selfie in the english language has increased by 17 000% since this time last year.”28 this social media phenomenon has created quite a bit of media hype in 2013. according to Jenna wortham, technology reporter for The New York Times, “selfies have become the catch-all term for digital self-portraits abetted by the explosion of cellphone cameras and photo-editing and sharing services. every major social media site is overflowing with millions of them. everyone from the pope to the obama girls has been spotted in one.”29 wortham also notes that “selfies often veer into scandalous or shameless territory — think of miley cyrus or geraldo rivera — and at their most egregious raise all sorts of questions about vanity, narcissism and our obsession with beauty and body image.”30 | |

Nadav Hochman, Lev Manovich, Jay Chow. 33292 photos shared on instagram in Tel aviv during april 22–26, 2012. From the project phototrails.net. digital image rendered with custom software 20 000x20 000 pixels. 2013 Publicity photo Courtesy of the artists | |

| Selfies have been called “a symptom of social media-driven narcissism,”31 a “way to control others’ images of us,”32 a “new way not only of representing ourselves to others, but of communicating with one another through images,”33 “the masturbation of self-image”34 and a “virtual “mini-me,” what in ancient biology might have been called a “homunculus” – a tiny pre-formed person that would grow into the big self.”35 lynn schofield clark, director of the estlow international center for Journalism and new media at the university of denver and author of The Parent app: Understanding families in the Digital age (oxford, new york: oxford university Press, 2013) has argued that selfies “can create a moment of playfulness that helps us to recognize the truth about living in culture that celebrates the individual and the spectacle. they can help us to deal with the absurdity of the ordinary in the face of all of that expectation of fame and spectacle.”36 mark r. leary, Professor of Psychology and neuroscience at duke university and author of The Curse of the Self: Self-awareness, egotism, and the Quality of Human life (oxford, new york: oxford university Press, 2004) and editor of interpersonal Rejection has pointed out that “by posting selfies, people can keep themselves in other people’s minds. in addition, like all photographs that are posted online, selfies are used to convey a particular impression of oneself. through the clothes one wears, one’s expression, staging of the physical setting, and the style of the photo, people can convey a particular public image of themselves, presumably one that they think will garner social rewards.”37 karen nelsonfield, senior research associate, ehrenberg-bass institute for marketing science, university of south australia, and author of Viral Marketing: The Science of Sharing (oxford, new york: oxford university Press, 2013) is most critical, and sees a calculated premeditation behind all the cute self-portraits posted online: “we now all behave as brands and the selfie is simply brand advertising. selfies provide an opportunity to position ourselves (often against our competitors) to gain recognition, support and ultimately interaction from the targeted social circle. this is no different to consumer brand promotion.”38 nelson-field’s argument sounds believable, as indeed most of the selfies posted to instagram seem to be positive, uplifting, flirtatiously playing with the endless possibilities of creating fictional identities that most typically are happy, accomplished, proud, well-dressed, partly or completely undressed, seductive or sexy – attempts at selfbranding. as casey n. cep has rightly noted, “all those millions of selfies filling our albums and feeds are rarely of the selves who lounge in sweatpants or eat peanut butter from the jar, the selves waiting in line at the unemployment office, the selves who are battered and abused or lonely and depressed. even though the proliferation of self-portraits suggests otherwise, we are still selfconscious.”39 Wortham offers a compelling preliminary summary of this ongoing discussion by suggesting that “rather than dismissing the trend as a side effect of digital culture or a sad form of exhibitionism, maybe we’re better off seeing selfies for what they are at their best — a kind of visual diary, a way to mark our short existence and hold it up to others as proof that we were here. the rest, of course, is open to interpretation.”40 among the multiple interpretations presented so far, it seems especially thrilling to view the selfie in the larger context of the history of photography and self-portraiture in general. often the term is applied retroactively to proto-selfies or self-portraits made in the nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century photography. these accounts inevitably start with robert cornelius’s selfie, a daguerrotype self-portrait made in 1839.41 kandice rawlings, art historian and associate editor of Oxford art Online asserts: “self-portraiture has remained one of the most interesting genres in photo history. it seems that from photography’s earliest days, there has been a natural tendency for photographers to turn the camera toward themselves.”42 among the reasons for this tendency is the construction of the self, the use of photography as a tool for performing the self and self-fashioning. what makes unpacking this construction even more complicated is the fact that photographic self-portraits offer ultimate control over our image which we are not able to see in an unmediated way. therefore many of the instagram selfies are taken in front of a mirror. the same problem has been encountered by artists and photographers. dawn m. wilson has pointed out that “in self-portraiture, an artist seeks to have the same kind of access to her own face as she has to the face of any other person whom she might choose to portray; this is why mirrors are invaluable: it is not possible to see my own face directly, but i can see my own face in a mirror.”43 in addition, wilson notes that especially “photography gives the artist access to otherwise inaccessible and unexpected features of her own appearance in new and creatively significant ways.”44 furthermore, in photographic self-portraiture, according to amelia Jones, “technology not only mediates but produces subjectivities in the contemporary world.”45 technology, and the new channels of dissemination of images in particular, is what makes selfies different from earlier forms of self-portraiture. rawlings notes that “on one hand, this phenomenon is a natural extension of threads in the history of photography of self-portraiture and technical innovation resulting in the increasing democratization of the medium. but on the other, the immediacy of these images – their instantaneous recording and sharing – makes them seem a thing apart from a photograph that required time and expense to process and print, not to mention distribute to friends and relatives.”46 the very raison d’être of a selfie is to be shared in social media, it is not made for the maker’s own personal consumption and contemplation. by sharing a selfie, people express their belonging to a community, or a wish to belong to one. as artist and critical thinker Paul chan has said, “in belonging we actualize ourselves by possessing what we want to possess us, and find fellow feeling from being around others who own the same properties. and by properties, i mean not only tangible things, like shovels or tangerines, but more importantly, the immaterial things that give meaning to an inner life, like ideas, or desires, or histories.”47 thus performing the self is a communal, public activity. the individual and unique (me) becomes part of “us,” a community, via means of a common platform for image sharing and a uniform image format in the case of instagram selfies. moreover, it is also exciting to explore the artistic and aesthetic aspects of the selfie. as often is the case with new trends, the conservative voices have hurried to claim that selfies definitely are not (and cannot be viewed as) a form of art. for instance, stephen marche argues that the ease of taking and disseminating selfies prevents these images from entering the rarified field of art: “we still think of photographs as if they require effort, as if they were conscious works of creation. that’s no longer true. Photographs have become like talking. the rarity of imagery once made it a separate part of life. now it’s just life. it is just part of the day.”48 i would like to keep in mind, however, that selfies have too much to do with creativity, artistic urge, and self-performance, that we cannot ignore this aspect. of course, it can be argued that selfies most likely are not an example of the decadent ‘art for art’s sake’ – which, of course, is still a valid slogan and can generate fabulous works – but rather ‘art for the people’, almost as lenin would have liked it. finally, everyone is an artist, just like beuys envisioned it. selfies have been exhibited in art museums, for instance, in the video installation National #Selfie Portrait Gallery at the national Portrait gallery in london, curated by kyle chayka and marina galperina.49 the camera manufacturer leica sponsored an open call for selfies in order to produce a coffeetable book.50 in brief, i would argue that selfies can and should be viewed also from the art historical perspective. Some field notes (That I Thought I understood...) How to reconcile these different approaches to the selfie, how to view the same images as data, and as a form of art, are among the questions explored by the current research in progress. the research team is led by manovich, other team members include: dominikus baur, data visualization and mobile interaction designer; daniel goddemeyer, researcher and strategic interaction designer; nadav hochman, Ph.d. candidate in history of art and architecture, university of Pittsburgh, and the main developer of the Phototrails project; moritz stefaner, information visualization designer; alise tifentale, Ph.d. candidate in art history, city university of new york; and mehrdad yazdani, designer. in addition, the team relies on work by several anonymous mechanical turks, whose functions will be described below. The research process involves several stages. in october 2013, instagram photographs that were taken during one week were downloaded and geotagged in central areas of the following five large cities: bangkok, berlin, moscow, new york and sao Paulo. from all the images, a random 140 000 images were selected for further analysis. in the next stage computational methods needed human input, and three mechanical turks were assigned to filter the images that are selfies and tag them according to their guesses regarding age and gender of the person portrayed. amazon mechanical turk is a virtual marketplace, an online platform for a global pool of workers – called mechanical turks – willing and able to do computer-based tasks (most typically simple, repetitive, and voluminous) for a few cents apiece. the wikipedia entry explains that the service is “using distributed human intelligence to help computer programs perform tasks that computers cannot do well.” 51 it is readily available and cheap human labour, briefly speaking. for companies, researchers, and even artists this has proved to be an efficient method of completing time and labour-consuming tasks in a short time, and avoiding all the responsibilities and extra expenses of an employer. testing, translation, transcription, comparing large amounts of images and / or texts, and double-checking the results obtained by software are some of the most typical assignments that mechanical turks perform.52 from the results provided by the mechanical turks, 640 images, 640 selfies per city taken and shared during one week in october 2013 then is the final data set of the ongoing research. currently, the team is working on analysis of these selfies, exploring the ways how software can help compare the visual style, composition, colour scheme, head position, facial expression, and many other variables in the selfies taken in the five cities. the final project presentation which will be online when this magazine is out will contain visualizations of the possible differences among selfies taken in these cities, an interactive web app, essays and more. The individual users of instagram in this case do not have much of an individual agency, their voice does not have a meaning unless it belongs to a collective, to a larger community that represents a city. the software studies approach is not interested in the individual images. we do not look into the subject of each photograph posted on instagram, we do not analyze the composition or any other artistic or stylistic choices that the users might have made while taking each individual photograph. instead, this approach considers the photographs as data and analyzes them accordingly, thus stripping the images from all possible emotional and aesthetic qualities, as well as avoiding even the slightest chance of discussing these images as examples of so-called ‘citizen journalism’ or ‘social documentary’. at the same time, the data is generated by real people, motivated by their real life experiences and excitements. according to manovich, “the goals of digital humanities’ analysis of interactive media will be different – to understand how people construct meanings from their interactions, and how their social and cultural experiences are mediated by software. so we need to develop our own methods of transcribing, analyzing, and visualizing interactive experiences.”53 the project attempts to cover different fields of inquiry – it focuses on one very specific platform of image sharing, and it is about social networking media in general. in a way, it still very much is about photography and self-portraiture. it is about testing the limits of capabilities of software designed to analyze large amounts of visual information and algorithmically extract visual features. as hochman sees it, “our project is an illustration of a potential way to study, navigate, visualize and “see” commonalties and differences in one, particular kind of these communities: #me.”54 1 www.complex.com/art-design/2013/10/future-of-design/lev-manovich 2 for a very useful insight into a digital humanities approach to pedagogy, see the online resource introduction to Digital Humanities developed by university of califor- nia: dh101.humanities.ucla.edu/. for a thoughtful discussion on the practical application of digital humanities in classroom settings, see marc Parry, “how the hu- manities compute in the classroom,” The Chronicle of Higher education, 6 January, 2014. m.chronicle.com/article/how-the-humanities-compute-in/143809/ 3 manovich, lev. “the algorithms of our lives.” The Chronicle of Higher education, 16 december, 2013. www.chronicle.com/article/the-algorithms-of-our- lives/143557/ 4 manovich, lev. Software Takes Command. new york, london: bloomsbury, 2013, p. 152. 5 ibid, p.156. 6 ibid, p. 156. 7 ibid, p. 335. 8 manovich, lev. Software Takes Command, p. 167. emphasis in the original. 9 manovich, Software Takes Command, p. 176. emphasis in the original. 10 manovich, lev. Software Takes Command. new york, london: bloomsbury, 2013, p. 331. 11 eggers, dave. The Circle: a Novel . new york: alfred a. knopf, 2013. 12 manovich, lev. Software Takes Command, new york, london: bloomsbury, 2013, pp. 336-337. 13 www.manovich.net/softbook/ 14 www.phototrails.net/about 15 itu prediction quoted from Jochan embley, “mobile phone subscriptions to equal global population by end of 2013.” The independent, 8 october, 2013. www. independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/mobile-phone-subscriptions-to- equal-global-population-by-end-of-2013-8866281.html. world population data from hwww.geohive.com. 16 heggestuen, John. “one in every 5 People in the world own a smartphone, one in every 17 own a tablet.” Business insider, 15 december, 2013. www.busines- sinsider.com/smartphone-and-tablet-penetration-2013-10. 17 rusli, evelyn m. “instagram Pictures itself making money.” The Wall Street journal, 8 september, 2013. online.wsj.com/news/articles/sb10001424127887324577304579 059230069305894 18 nadav hochman and lev manovich, “zooming into an instagram city: reading the local through social media.” first Monday 18: 7 (1 July, 2013), n.p. firstmonday.org/ ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/4711/3698 doi:10.5210/fm.v18i7.4711 19 manovich, lev. Software Takes Command. new york, london: bloomsbury, 2013, p. 179. 20 hochman and manovich, “zooming into an instagram city,” n.p. 21 all works that were included in the exhibition can be viewed online: photo- trails.net/exhibition. 22 museemagazine.com/culture/art-out/the-aggregate-eye-at-amelie-a-wallace- gallery-october-29-december-5-2013/ 23 www.complex.com/art-design/2013/11/2-million-instagram-photos-the-aggre- gate-eye-exhibition 24 casey reas’s exhibit was on view from 5 september to 12 october, 2013. more on the exhibit: www.bitforms.com/exhibitions/casey-reas-ultraconcentrated 25 holmes, kevin. “casey reas launches new exhibition at bitforms gallery.” The Creators Project, 5 september, 2013. thecreatorsproject.vice.com/blog/casey- reas-launches-new-exhibition-at-bitforms-gallery 26 reas.com/information 27 blog.oxforddictionaries.com/press-releases/oxford-dictionaries-word-of-the-year-2013/ see also the wikipedia entry on the selfie: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ selfie 28 blog.oxforddictionaries.com/press-releases/oxford-dictionaries-word-of-the- year-2013/ 29 Jenna wortham, “my selfie, myself.” The New York Times, 19 october, 2013. www.nytimes.com/2013/10/20/sunday-review/my-selfie-myself.html?smid=pl-share 30 wortham. “my selfie, myself.” 31 www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/australiaandthepacific/austra- lia/10459115/australian-man-invented-the-selfie-after-drunken-night-out.html 32 blog.oup.com/2013/11/scholarly-reflections-on-the-selfie-woty-2013/ 33 rawlings, kandice. “selfies and the history of self-portrait photography.” Oxford University Press Blog, 21 november, 2013. blog.oup.com/2013/11/selfies-histo- ry-self-portrait-photography/ 34 www.esquire.com/blogs/culture/selfies-arent-art 35 www.cnn.com/2013/11/23/opinion/clark-selfie-word-of-year/ 36 blog.oup.com/2013/11/scholarly-reflections-on-the-selfie-woty-2013/ 37 blog.oup.com/2013/11/scholarly-reflections-on-the-selfie-woty-2013/ 38 blog.oup.com/2013/11/scholarly-reflections-on-the-selfie-woty-2013/ 39 cep, casey n. “in Praise of selfies,” Pacific Standard, 15 July, 2013. www. psmag.com/culture/in-praise-of-selfies-from-self-conscious-to-self-construc- tive-62486/ 40 wortham, “my selfie, myself.” 41 see, for instance, nypost.com/2013/10/17/the-art-of-taking-selfies-is-nothing- new/, or mashable.com/2013/07/23/vintage-selfies/. 42 rawlings, “selfies and the history of self-portrait photography.” 43 wilson, dawn m. “facing the camera: self-Portraits of Photographers as artists.” The journal of aesthetics and art Criticism 70, no. 1 (2013): 58. 44 wilson, “facing the camera,” p. 62. 45 amelia Jones, “the “eternal return”: self-Portrait Photography as a technology of embodiment.” Signs: journal of Women in Culture and Society 27, no. 4 (2002): 950. emphasis in the original. 46 rawlings, “selfies and the history of self-portrait photography.” 47 chan, Paul. “what art is and where it belongs,” e-flux journal no.10 (november 2009). www.e-flux.com/journal/what-art-is-and-where-it-belongs/. 48 marche, stephen. “sorry, your selfie isn’t art,” esquire, The Culture Blog, 24 July, 2013. www.esquire.com/blogs/culture/selfies-arent-art 49 www.moving-image.info/national-selfie-portrait-gallery/ www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/02/leica-myself_n_3694899.html www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/amazon_mechanical_turk seewww.mturk.com. 50 www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/02/leica-myself_n_3694899.html 51 www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/amazon_mechanical_turk 52 See www.mturk.com. 53 manovich, lev. “the algorithms of our lives.” 54 hochman, nadav. “the fragmented image.” december 2013. essay from a work in progress, unpublished (as of 6 January, 2014). | |

| go back | |