|

|

| The Master and Wilnis Laine Kristberga, Screen Media and Art Historian | |

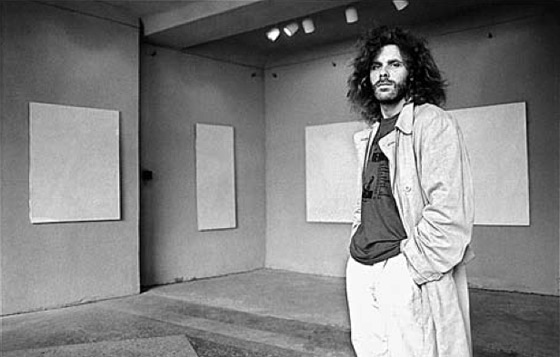

| Vilnis Zābers (1963–1994) is an uncommonly interesting and bright star in the sky of Latvian art history. Judging by the scope of his art istic range – painting, graphic art, installations, performances, liter ary texts – the metaphor of nomad seems applicable to him as an artist. Zābers thought and effortlessly moved around various artistic genres and categories, stating in an interview that “it is not inconsis tency. Rather I would say I quickly lose interest in one material”1. The second factor that must be taken into account when analysing Zābers’ art is character traits such as attractiveness and eccentricity which in his short life used to become apparent through his styling of a per sonal image different to his peers and – as his contemporaries recall – bursting into thunderous laughter “totally out of place”2. The cre ative nomadism in combination with an explosive personality ap pears to be the reason why in his oeuvre the elements of play and playing become evident, which in the framework of Latvian art in the 1990s and today could be analysed both in terms of conceptual art and manifestations of NeoDada or neoavantgarde. Play as a creative force, and life as art, has been a characteristic of many movements, including Fluxus, Dada and Bauhaus. As empha sised by Johannes Itten, one of the Bauhaus teachers, “play becomes celebration; celebration becomes work; work becomes play”3. Similar dichotomies between seriousness and jokes, academism and play can be observed in Zābers’ works of art. The most serious in tone seems to be the largescale series painted in white, greyish and bluish shades that was exhibited in 1990 in his solo show under the same title I Solo Show. Ingrīda Zābere remembers that the artist created the works in author’s technique: “He had his own special technology. First, the paint was spread on with a piece of plastic, then it was pol ished with sandpaper, then another layer of paint was spread on un til the surface became pearly and, when touched, felt smooth as silk. When looking at these paintings, it seemed they were vibrant and glittery, shining with light. It was fascinating!”4 Conceptually these works resonate with Barbara Gaile’s paintings – the artist similarly works with the texture and paint, devoting special attention to smoothing out, rubbing and polishing the paint. Both artists have used nacre pigments to achieve the effect of pearliness and illusory glimmer, although Zābers mostly tried to achieve this solely with polishing. Seriousness and abstractions are manifested in other paintings, for instance, in those that were done in 1994 and were offered to the public in Zābers’ commemorative exhibition in 1995. On most occasions the artist left these paintings without titles, therefore it is difficult to analyse them as individual artefacts. However, these paintings have a common conception. Unlike the peaceful, harmon ic atmosphere of the white series, the paintings of 1994 are more striking with greater dynamism, both in terms of the composition and the technique. The paint has similarly been spread in layers, merging and forming unnoticeable transitions, yet they only fulfil the role of background. The top layer consists of monolith geomet ric areas that contrast with nervous paint splashes in the manner of Jackson Pollock.5 Also, transparent lines carefully marked or trans ferred with stencil are evident; these take on cylindrical and at times erotic shapes. As can be noticed in an unfinished work from this se ries of abstract expressionism, the paintings have been done in a sim ilar way to the drawings of the time. First, the surface of the painting was covered with a fine network of circles and lines, creating the de piction of a complicated mechanism. The carefully structured laby rinth illustrates both the direction of the artist’s thoughts and his intention to activate the viewer’s imagination. Yet due to the fact that imagination is individual and subjective, this approach has the character of accident, and it may be considered as an element of play in Zābers' art. | |

Vilnis Zābers. 1990 Publicity photo Courtesy of Ingrīda Zābere | |

| Of course, the artist’s playing is expressed most vividly in the genres that are indirectly related to drama or staging a scene, and here performance art must be mentioned. Zābers participated in vari ous actions, both as a member of the artists’ union LPSR-Z 6 founded at the end of the 1980s and also in tandem with Miervaldis Polis, ac cording to whom Zābers was “born a performance artist. Any public appearance was like an entrance on stage. He simply could not live any other way.” 7 Besides, at the beginning of the 1990s, performance belonged to those art forms that were foreign to Soviet art and thus less familiar locally.8 Actions and performances in the city environ ment as unofficial own initiatives by artists changed the dialectics of the relationship between the viewer and the work of art. From being a passive observer, the viewer had the opportunity to become interactively involved, and even to become part of a work of art, be cause his or her opinion or counterreaction sometimes was the miss ing and necessary link in the chain.9 As it may be concluded from the press reviews of the time, the public did get involved in Zābers’ and Polis’ performances. For in stance, in the action Sunflower seed sellers of 8 August, 1991, Zābers, who was dressed in everyday clothes with a socalled tibiteika [Uz bekistan traditional hat – Ed.] on his head, and Polis, in the image of the Bronze Man, sold sunflower seeds on Brīvības boulevard by the Laima clock. Zābers offered passersby ordinary sunflower seeds, while the Bronze Man sold the more expensive – bronze – seeds. As a result, Zābers sold more than 90 glasses and cashed in 90 roubles, but Polis managed to sell only one glass of seeds to a foreigner – how ever, for five dollars (which according to the exchange rate of the time was more than 100 roubles). The spectators had also asked all kinds questions, for example, Polis was addressed a question regard ing his makeup and whether it was not too hot to stand in the sun like that.10 Most likely, this performance seemed funny and comic to those watching, yet the intention of the artists can be interpreted as an ironic commentary on topical issues under the circumstances of economic and political restructuring in Latvia of the 1990s. In the duet of Zābers and Polis it is not difficult to spot a likeness with the British artists Gilbert and George, who are an inseparable pair, both in art and in life.11 Polis’ Bronze Man especially echoes with the tableau vivant performance of Gilbert and George from their student period titled Singing Sculpture which was also performed on the streets of London in 1970 for the joy of passersby. Dressed in suits, and having smeared their faces and hands with a metallic gloss makeup, the British artists in mannequin poses sang along to a musichall song from the 1930s about the melancholic joys of a homeless person, sometimes eight hours in a row. Later on, similar sculptures were made, for instance, Relaxing Sculpture and Drinking Sculpture. Like the Dadaists, Gilbert and George, too, claim that any thing they do is art. “There is no division between ourselves and our production. The division that exists for normal artists doesn’t exist for us. We and our work are completely together. This house, this stu dio, our lives, and these pictures and our viewers – the whole thing is one big object – all based around ourselves.”12 Gilbert and George’s statement that they are not “normal” art ists emphasizes the cultivation of “otherness”, which in their case is also underlined by being of the same sex and the fact that both are “boys from the countryside”. For Zābers, too, having arrived in Riga from Lubāna (Latvian town, 200 km east from Riga), it was important to be different from others, manifesting this in an ever changing personal appearance (at times with long and curly hair, at times – a shaved head) and attracting attention to the way he was dressed with an outfit bought from secondhand shops, flea market “Latgalīte”. Perhaps it was some kind of counterreaction to the mo notony dominating the 1980s, when “everybody dressed the same”13 and the fashion industry, beyond mass production, did not exist. However, in the 1990s the “otherness” was important, and it could be well demonstrated in the framework of interdisciplinary activities that included music, fashion and text, and expressed in such events as, for instance, the Untamed Fashion Assemblies.14 Contemporaries also credit Zābers with the image of a dandy that makes one involuntarily draw parallels with the slender silhouette of Kārlis Padegs. It was from Gilbert and George, it seems, that Zābers also bor rowed the motto of life as performance. There was an appreciable element of play in the One Day Exhibition that opened in 1992 at the gallery Kolonna. In this exhibition, Zābers and Polis welcomed the guests invited to the opening of the exhibition in an empty gallery – if anybody wanted to, they could consider the artists themselves as the only works of art. As indicated by Polis, this action is not to be treated as a reference to the exhibition Emptiness organised by Yves Klein in a totally empty gallery in Paris in 1958. Rather, the authors’ intention was to provide an ironical commentary on the exhibition opening events popular at the time,15 to which the guests invited by the organising institution often attended without any particular in terest in the works exhibited. The main goal was to socialize and to have fun. Zābers and Polis satisfied this desire by giving the viewers what they wanted, only in this context it must be regarded as a ges ture directed against the authority of the gallery and the curator, as well as the institutionalisation of art. A similar action was once car ried out by the Serbian artist Tanja Ostojić, who surprised the guests invited to a gallery in Rome, sitting naked in a bath together with a curator. This performance was intended as an imitation of a sexual intercourse, providing the opportunity for guests and artist to “be come one”. It must be noted that the culmination of this merging was the moment when the art critic, too, joined the artist and the curator in the bathing activities.16 | |

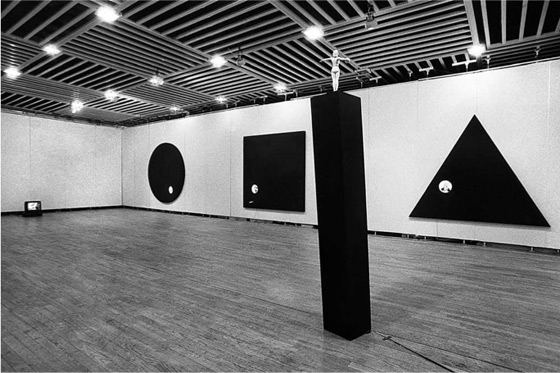

Vilnis Zābers. Ocupation of Rome. Installation. View from the exhibition Zoom Factor at the exhibition hall Latvia. 1994 Publicity photos Courtesy of Ingrīda Zābere | |

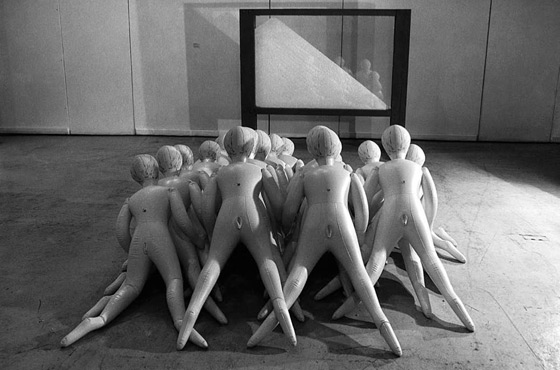

| Although Zābers and Polis together presented only three per formances, these caused huge resonance in the press of the time, and, it seems, in Latvian contemporary art in general. However, as stated by Ingrīda Zābere, a more significant duet was Zābers and Normunds Lācis. Their joint actions were expressed through com munication with society in a special language that they had created over the course of several years: via coded texts and signs in cartoons in the press, in drawings and illustrations, as well as conversations and interviews17. For instance, Alvis Hermanis remembers that once Zābers phoned at 3am and asked whether he could come and visit. On opening the door, Hermanis was ceremoniously handed a gift wrapped in paper – the winner’s prize. As explained by Lācis, the idea to visit someone had occurred to Zābers in the middle of the night. A special table was drawn up on squared paper, where on the vertical axis the names of friends and acquaintances were written down, but on the horizontal axis – additional information regarding their address, whether they lived on their own, together with parents or with a girlfriend, etc. Afterwards the “superfluous” candidates were crossed out and calls were made to the finalists. Hermanis was the only one who had not cursed rudely at Zābers, therefore he be came the recipient of the special award – an unfinished drawing by Zābers without a signature.18 Such mundane shenanigans can hardly be termed as actionism on a wider scale, yet it characterises Zābers’ unofficial approach in defining the object of art, as well as the ele ment of play in the process of creating art. Installation art can be viewed as another expression of the cre ative nomadism in Zābers’ artist’s biography. They are two installa tions of wide scope, one of which with the ambiguous title Ocupation of Rome was set up at the exhibition Zoom Factor organised by the SCCA– Riga in 1994, but the other one titled The End of the Empire was exhibited at the exhibition The State also in 1994, however, after Zābers’ death. In the description of the work, Taking Rome is justly termed a video installation. It consisted of three geometric planes – a circle, a square and a triangle painted in electric blue, in which tiny viewing glasses with pornographic photographs were installed. On a pedestal painted in a similar ultramarine blue, a white statuette – the super gymnast from Stalin’s epoch – rotated. On the floor there was a TV screen, where blue flashes alternated with excerpts of por nographic films. It is notable that the implementation of this work differs from the draft, where initially the artist had planned five wooden objects at the height of 2.5 metres, painted in black and at tached to the wall. In one of the objects it was planned that there would be a crack through which the viewers would see a porn video. This would illustrate the contact of two planes, both in the form of sexual intercourse and by fixing perpendicular smaller objects into the big wooden objects. The draft sketches also contained copies from a book on the history of Ancient Rome, where the sexual lives of Romans were described, and which, in turn, perhaps had encour aged Zābers’ reflexions on the subject. In the installation The End of the Empire the artist had similarly planned pornographic elements that, according to the intentions il lustrated in drafts, were not fully implemented. At the exhibition The State, the public were confronted with a pyramid of inflatable dolls or artificial women that had become popular in the sex shops in the 1990s. The dolls were “looking” at an object made of glass that had been filled with salt and put in front of them. The dolls thus repre sented a group of viewers, or crowds in a wider context. Although in Zābers’ drafts this idea was sketched in, the gaze of the pile of dolls in the exhibition was not directed at a blue cube, where a porn film was to be projected, or – in the second version – at an aquarium with fish calmly swimming around in it. In the guidelines for the exhibition Zābers had written: “Studying pornography only and solely through the prism of the visual image.” These conceptual installations are a true example of a seman tic polyphony. Although the first verdict which perhaps occurred to the postSoviet viewer, too, is provocation, the works also contain an additional layer of meanings. Although pornography, especially in the context of feminism, is regarded a representation genre where women are exploited and dehumanised by turning them into dumb objects,19 in the framework of contemporary art there are plenty of works that one could be described as pornographic. The paintings of John Currin, the neon sculptures of Bruce Nauman, the stitching and textile art of Ghada Amer, the collages of Paul McCarthy, the photo graphs of Thomas Ruff, the statuettes of Jeff Koons, the installations of Judy Chicago, and the bronze sculptures of Marc Quinn come to mind, but this list could be continued. Yet it must be noted that these are works of art that mimic, criticize, or reference pornography, but arguably are not themselves pornography.20 Zābers’ works, too, must be viewed in this kind of critical con text. As Michel Foucault argues in his threepiece research ‘The His tory of Sexuality’, with the rise of the bourgeoisie any expenditure of energy on purely pleasurable activities has been frowned upon. As a result, sex has been treated as a private and practical affair that only properly takes place between a husband and a wife. Sex outside these confines is not only prohibited, but repressed, this being mani fested in efforts to turn it into something unthinkable and not to be talked about. A similar idea has been expressed by Sigmund Freud in his ‘Civilization and its Discontents’, observing that “the genitals themselves, the sight of which is always exciting, are hardly ever re garded as beautiful”21. From this it seems to follow that “we only get beauty if we do not depict the site of sexual pleasure directly”22. Whereas, when attending the exhibition Art and Sex at the Bar bican Gallery in 2007 in London, one could draw a conclusion that sex is neither an unchanging historical constant, nor a primordial drive fighting to be free of repression, but rather a phenomenon that in various cultures is constantly being made and remade. Thus the pornographic elements in Zābers’ art can also be viewed as attempts to deconstruct pornography as a representation mode. In the post Soviet space such deconstruction was manifested both by bring ing in the issues of feminism and by organising a violent attack on the viewer’s vision/gaze, which can be illustrated with the help of the metaphor portrayed in Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel’s film Un Chien Andalou (cutting the eyeball open with a knife). To some ex tent Zābers acts as a psychoanalyst, offering the hidden, concealed and repressed agenda from the previous political regime for pub lic viewing. Yet here, too, the unifying feature is the element of play, which in this case turns Zābers into a manipulator, but the viewer – into a guinea pig. Elements of the erotic also appear in the works of miniature graphic art that were exhibited at the 4th Riga Miniature Graphic Triennial in 1993 at the centre of which was a nude female body from the photographs of erotic magazines. In these works of art Zābers played not only with the subject of the works, but also with the cho sen technical approaches. The graphic works were created using a mixed technique – collage, drawing and photocopies, thus the artist had preferred alternative methods of creating the image as opposed to academically more formal graphic approaches. In the genre of graphic art that Zābers had studied at the Academy of Art, the artist often tried to be innovative and explored ways of creating a work of art with untried and untested techniques. | |

Vilnis Zābers. The End of the Empire. Installation. Oļegs Tillbergs and Kristaps Ģelzis relised this project by Zābers‘ skeches. View from the exhibiton State at exhibition hall Arsenāls. 1994 Publicity photo Courtesy of Ingrīda Zābere | |

| For instance, when the first copying and printing machines Xe rox had just appeared in Latvia, Zābers invented an author’s tech nique where he mixed etching, drawings, collage and photocopies. First, the etching paper was soaked in acetone, then it was covered with photocopies. At the last stage of work, the printing press at the Academy was put to use, achieving the imprint of the graphics, which had dissolved in acetone, on paper. These were supplemented with etching proofs, drawings, pieces of tissue paper and various textures, creating collages. This technique was used when working on the se ries Dance Around the Circle, where the unifying elements were two images – a ballerina and a boy juggling on a penny farthing bicycle, as well as the cycle of graphic art works presented as Zābers’ diploma work on graduating the Academy of Art, which in 1990 was exhibited at gallery Kolonna. These largescale graphic works were intended as homage to the American graffiti artist Keith Haring, who died of AIDS. Zābers used one of the last photographs of Haring as the basis for the work, and this photograph was repeated both in fragments and in the whole cycle in general. Zābers’ countless drawings, caricatures and illustrations also belong to the genre of graphic art. Here, the virtuosity of the fine line is at the basis of the artist’s handwriting. Here playing is manifested through the choice of images that often are satirical and grotesque as well as erotic, and in the intensity of the line, improvisation and explo sive, instantaneous creation. Text, too, becomes a platform of graphic art, written down in different handwriting on the paper. Mostly they are aphoristic miniatures in the style of haiku, for instance: Someone reads life from a hand A dog, a cat eats It’s so easy for you Garments flutter in the night dance From the wind that’s raised Green tea in a cup awaits. Vilnis Zābers has left behind remarkable works of the neoavant garde, where his manifold personality and play as the principle of creative force have been revealed. Demonstrating with certainty that there are no disciplines where he could not be innovative and outstanding, Zābers created about him an impression of the artist nomad. The inexhaustible, creative energy where, it seems, the Apol lonian and its opposite the Dionysian interacted, lay at the base of the diversity of his artistic platforms and creative transformations. Whether a serious conceptualist, eccentric dandy or the actor of life, Vilnis Zābers created art with a reminder that not always should it be carefully calculated space must be left for accident and play, too. Translator into English: Laine Kristberga 1 Bankovskis, Pauls. Divas horizonta attiecības. Literatūra un Māksla, 1992, 7. febr., p.16 2 Par Vilni Zāberu (1963–1994). Compiled by Ingrīda Zābere, Inese Baranovska. Riga: Latvijas Mākslinieku savienības galerija, 2003, p. 63 3 Droste, Magdalena. Bauhaus: 1919–1933. Köln: Taschen, 2002, p. 37. 4 Par Vilni Zāberu (1963–1994), p. 96 5 The seemingly accidental splashes were planned, in order to create texture in certain areas (as opposed to Pollock). Zābers also stated himself that “I don’t have any relationship with Jackson Pollock”. See: Rudzāte, Daiga. Vilnis Zābers. www.studija.lv/?parent=1579. 6 Normunds Lācis, Vilnis Putrāms, Māris Subačs, Artis Rutks, Vilnis Zābers. 7 Raiskuma, Ieva. Zābera uznāciens. Labrīt, 1995, 2. febr. 8 Traumane, Māra. Contemporary Art: Public Space, Influence of the Media and Communication Strategies in the 90s. In Deviņdesmitie. Riga: Laikmetīgās mākslas centrs, 2010, p. 124 9 For instance, Juris Boiko did not view negatively the objects in the installation Environmental objects that were damaged by the public in 1988, claiming that “this defacement and damage incident was the best reaction to art” and that “it was a challenge to do something”. See: Deviņdesmitie, p. 122 10 Bergmanis, Andris. Kā kļūt par miljonāru? Sestdiena, 1991, 17. aug. 11 As stated by Zābers: “I have a relationship with Gilbert and George, but I don’t have a relationship with Jackson Pollock”. See: Rudzāte, Daiga. Vilnis Zābers. www.studija. lv/?parent=1579. 12 Quoted from: Gilbert & George: Life, a Great Sculpture. In: Carnegie International. Pittsburgh: Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, 1985, p. 136. 13 Astahovska, Ieva, Krese, Solvita. Meklēt pludmali zem asfalta. In: Deviņdesmitie, p. 484 14 Ibid. 15 According to Māra Traumane’s findings, in Latvia the role of the curator or the institution, gallery or art centre had become crucial in the 1990s under the circumstances of art institutionalisation. See: Deviņdesmitie, p.123 16 Kristberga, Laine. Ķermenis kā politisks instruments un mākslas platforma Taņas Ostojičas darbos. Studija, 2010, Nr. 75, p. 48–53 17 Sk.: Rudzāte, Daiga. Vilnis Zābers. www.studija.lv/?parent=1579. 18 Par Vilni Zāberu (1963–1994), p. 87 19 “Pornography makes women into objects. Objects do not speak.” (Catherine MacKinnon) Quoted from: Sexual Solipsism: Philosophical Essays on Pornography. Rae Langton. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2009, p. 4 20 Art and Pornography: Philosophical Essays. Ed. by Hans Maes and Jerrold Levinson. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2012, p. 2. 21 Freud, Sigmund. Civilization and its Discontent. New York: Norton, 1961, p. 83. 22 Danto, Arthur Coleman. The Abuse of Beauty: Aesthetics and the Concept of Art. Illinois: Carus Publishing Company, 2003, p. 82. | |

| go back | |