|

|

| Maija in the inside-out world Indrek Grigor, Art Critic, Curator Inside and Out 29.11.2012.–13.01.2013. kim? Centre of Contemporary Art | |

| Participating artists: Patrik Aarnivaara (Sweden), Kasper Akhøj (Denmark), Christian Andersson (Sweden), Ēriks Apaļais (Latvia), Zenta Dzividzinska (Latvia), Elsebeth Jørgensen (Denmark), Flo Kasearu (Estonia), Cato Løland (Norway), Julija Reklaitė (Lithuania), Anngjerd Rustand (Norway), Shirin Sabahi (Sweden/Iran), Oļa Vasiļjeva (Latvia/Netherlands), Iliana Veinberga and Ainārs Kamoliņš (Latvia). Curator: Maija Rudovska Creative research as a genre of art has by now probably lost its high point in mainstream art, but its discursive influence in writings about art will in all likelihood remain strong for quite a long time. The phase of active experimentation and self-validation have, however, been replaced by an analytical situation and therefore it is time to ask whether this investigative approach changed something in art and, if so, what was changed and to what extent. For myself, an even more important question arises that seems to also fit the context of the exhibition Inside and Out: how and to what extent did the liberal use of scientific terminology influence art research? These questions, however, are very big and require deeper analysis – a strength for which I find myself lacking – but the possible transformation of scientific methodology should still be considered the central problem of this article. Before getting to the exhibition itself I would like to add by way of explanation that, when talking about the differences between science and art as methods of modelling reality, the article uses Yuri Lotman’s chrestomathic definition: “Scientific model recreates the object’s system in an illustrative manner. It models the “language” of the system that is being studied. The artistic model recreates the object’s “speech”. But in relation to that reality, which is being approached through the prism of the artistic model that has been acquired previously, this model takes the form of language that discretely organizes the new impressions (speech).”(1) The exhibition Inside and Out is a curatorial project of the Latvian art historian Maija Rudovska. As a researcher, Rudovska has studied Soviet architecture and through this also the problems of social and political space. These aspects are also present in the current exhibition. What’s more – they are not merely present through the content of the show, but the subtitle 11 Notes, a Study and a Publication infers a methodological approach. “Inside and Out started as a study of space and spatial structures, their relations, which are constituted by the historically and socially constructed assumptions.” (Quoted from the press release.) This shows that the curator conceptualizes her work as research. The general dismissive assumption (founded as well as unfounded) about curatorial research equates curators’ activities with those of scientists, who, according to Lotman, pose a hypothesis and use that as the basis for constructing a fixed model of the artistic reality that surrounds them. Rudovska’s curatorial practice, however, allows the assumption that she tried to carry out her research by following the method of artistic modelling. Thus the curator compiled the exhibition out of a selection of artists and their works, but this selection didn’t follow a preconceived system into which her vision places these works. Her aim, rather, was to use the provisional model that arose out of the works selected for the exhibition to rethink the object that interested her as an art historian: the space. | |

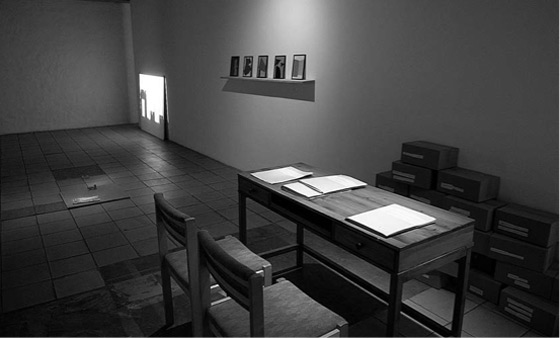

Iliana Veinberga, Ainārs Kamoliņš. So the Last Shall Be the First Culture-theoretical study, installation. 2012 Publicity photo Courtesy of the kim? Contemporary Art Centre | |

| This assumption that I make about the curator’s intentions is proven to be true by Rudovska’s decision to work first and foremost with living artists, and to use a gallery instead of a museum. The exhibitions held at museums are bound to be dominated by scientific modelling, since the works already exist and don’t offer any special surprises. Breaking established canons by re-contextualizing art works can create upsets in tradition, but this only represents the substitution of an established model with one based on a new hypothesis. The burden of previous interpretations forces the curator to view the work as an act of speech with a cultural and historical background, and impedes its capabilities to function as a work of art that takes the form of language. It is, however, characteristic that although Rudovska tried to avoid a fixed view at every step, the clearest failure in this approach occurred with the inclusion of the only deceased artist of the exhibition – by including an object that is part of a museum collection. Zenta Dzividzinska’s Contact Prints Book 1 (1965) is not intended to be an art work by the author and supposedly is also marked as an archival object by the museum. It consists of the contact sheets of the negatives by a young photographer that were made for purely technical reasons. Rudovska is right when she claims that this is a great example of an object that has no fixed position. It is a collection of materials of which most can, at best, be viewed as documentation. But some became, and some had the potential to become, actual art works. However, since the author herself didn’t see this album as an art work, it was open to an unlimited number of interpretations when people started considering it an object of art, because it lacked even the most minimal means of protection that the intended creative output of an author enjoys. In other words, the interpretation of this album as an art work has its roots directly in the vision of the curator – despite her poetic explanations about the boundless means of interpretation that the album offers, she still, first and foremost, uses it at her exhibition as a material to fill a semantic position demanded by the curatorial hypothesis. At the same time, Rudovska’s aim was to mount an exhibition of works that don’t have a set position in her own mind, since these works should be the basis of the curatorial conception and the foundation of the hypothesis. This would be the only way how an exhibition as a method of research could be a real alternative to scientific analysis. Elsebeth Jørgensen’s video Ways of Losing Oneself in an Image... that depicts her working with uncatalogued archive materials seems to be a similar flop. The video talks about how the material becomes unrecognizable, but this is more a projection of the desires of the curator herself that are brought about by the process of making the exhibition, rather than the problem of spatial transgression that is the central theme of the exhibition. Shirin Sabahi’s Swede Home is a selection of videos filmed in Iran by the Swedish engineer Jan Edman in the 1960s and 70s, and commented by the author thirty years later. The subject matter and the artist’s background as an Iranian emigre, however, give the impression of safe sailing in the currents of the mainstream by both the artist and the curator. Cato Løland, however, is an example of a living artist who offers resistance to the curatorial discipline. Løland‘s works mostly comprise kim? as an exhibition venue itself, its architecture and its surroundings. For a curator it is very difficult to control an artist who uses such a method. Especially if controlling is not their intent from the beginning. Thus if we follow the assumption that the curator wanted to achieve a situation where the object of research didn‘t have any predispositions to observation, it can be said that if Zenta Dzividzinska was set to fail already from the start, then Løland was the safest choice of the whole selection. I proved the curator‘s “self-destructive” intention above by referring to the choice of space for the exhibition (gallery vs. museum). Another indicator that is, however, somewhat more banal, is the choice of the theme: the third space. “Third Space has potential that may serve as focus shifting or give an opportunity [to] view things from a different angle, re-estimate the conventional...”(2) Rudovska‘s endeavours in finding a third space seem to mainly get stuck in the language barrier (remember that science models the language of a system) – her conviction that the third space is a space. The indicators of this entrapment, for example, are Ēriks Apaļais‘ painting Untitled (2012) which depicts the vast emptiness of space with lone floating details, and Kasper Akhøj‘s presentation Untitled (Schindler/Gray) (2006) that consists of 100 slides and sound. One of the reasons for the latter’s inclusion seems to be that its combination of documentation and fiction complements Zenta Dzividzinska’s album discussed above. The other reason for selection might lie in the fact that the tabloid whodunnit it talks about is illustrated with 100 black-and-white slides depicting two real residential buildings that are masterworks of modernist architecture but have otherwise no connection to the story whatsoever. The only artist who seems to have overcome the curatorial concept of space is Oļa Vasiļjeva. The reason for the artist‘s inclusion was probably the absurd scenographic composition that she creates. But if Løland managed to incorporate the exhibition space itself into his works, then Vasiļjeva‘s conceptualist composition of scarves on a clothes hanger and a cup full of pencils left on the floor does not have any genuine potential for narrative in the context of the overall exhibition. If we now, as a conclusion, come back to the question that I posited at the beginning of this article – what did science gain from using research as a method in art? – then viewing the curatorial work of Rudovska as an art historian in the aforementioned manner offers us the opportunity of saying that in addition to creating terminological chaos, the adaptation of scientific terminology in art offered art historians a way of understanding the exhibition as a research method through the offset of descriptive language. This doesn‘t mean that an exhibition could be accepted as an academic method since, as was also stated at the beginning, scientific and artistic modelling are inherently different. But the conscious and non-judgmental acknowledgement of these differences offers us a chance to not only politicize the transgressional third space that separates these two systems, but also to activate this transgression in a broader sense. Translator into English: Maija Veide (1) (Lotman, Juri 2006 “Kultuurisemiootika”, Tallinn, Olion, pp 24–25.) (2) Inside and Out: Selected writtings. Ed. Maija Rudovska, Zane Onckule. Riga: kim?, 2012 | |

| go back | |