|

|

| The phenomenon of Imants Lancmanis Sniedze Sofija Kāle, Art Historian Imants Lancmanis. The Story of an Apple 08.09.–01.10.2011. Riga Gallery | |

| To what extent does a phenomenon earn value in our opinions only because it is unique or, on the contrary, quite commonplace and familiar? How much would we be fascinated these days by paintings emulating the style of the 17th, 18th, 19th century if we had our own Hermitage, Prado, British Museum or Louvre? These questions haunted me again after viewing Imants Lancmanis’ latest solo exhibition Ābola stāsts (‘The Story of an Apple’), his retrospective at Riga Gallery. Perhaps we live in an era when everything currently being created inevitably reminds us of works of art already created before? There is nothing for it but to recall the creed of Mannerist artists: that everything outstanding had been discovered by the titans of the Renaissance and the only thing left for them was to retreat into extravagancies, in order to conclude yet again how cyclic the development of humanity and art actually is. As early as 1918 and 1922, Oswald Spengler, when launching the first and the second volumes of the book ‘The Decline of the West’, foresaw the imminent demise of Western European culture; still, could the blossoming of all genres of art in the 1960s that introduced a conceptually refreshing approach be regarded as a swan song? These notions, despite attempts to verbalise the interrelationships of cultural development/stagnation, are more of an individual character, just like certain people have a predisposition towards the days of yore. | |

View from the Imants Lancmanis' solo exhibition 'The Story of an Apple'. 2011 | |

| The oldest part of Imants Lancmanis’ retrospective – Dāvana mania sievai (‘Gift to My Wife’, 1987–1989), Vanitas (1996), Asaru diena. Sievas portrets (‘Day of Tears. Portrait of My Wife’, 1999), Vanitas ar balto tauriņu (‘Vanitas with the White Butterfly’, 2004) – very closely imitate the painting styles of the past, and the present day can be recognised or sensed only through the tiniest detail. Possibly if a person has lived in the apartments of the Rundāle Palace for years on end and invested their entire heart and soul into the place, they develop their own reality of past centuries. Likewise, the continued and invaluable work of research in Latvian art history, due to which a number of important publications about palaces and manors have come out, gradually shape a different perception of reality. If the paintings of the 1980s and 1990s are more a homage to the painting styles of the past centuries, then the series Kalētu klēts (‘The Kalēti Granary’, 1998–1999, 2005–2006) and Piektais bauslis. Revolūcija un karš (‘The Fifth Commandment. Revolution and War’, 2006–2009) display a welcome synthesis, where the upheavals in our history are retold with a modern empathetic approach. With an enviable attention to the minutest detail, Imants Lancmanis studied historical sources, captured the most diverse changes in nature, depicted himself and his colleagues to create figurally symbolic and, yes, also moralising paintings. The exhibition titled The Fifth Commandment. Revolution and War, nominated for the Purvītis Award and presented as a retrospective, could be named as the most striking. In 2011 it was deservedly displayed among other works of contemporary Latvian art, and not just because the pictorial language deployed may have charmed jury members. Quite on the contrary, it was a conceptual gesture, with which to reduce at least partly the black holes in our historical awareness, by using a particular kind of sign language and theatre in art. This series of paintings formed a kind of a playing arena, where each character was endowed with a role and significance devised by the artist; thus the themes that were touched upon and the way they were presented was more like a psychodrama, and precisely through this they acquired their unique character. For me as a resident of this world the horrors of war and the end of the world were understandable and to be re-lived, sensing the mutual confrontation between life and death, but the Latvian part seemed even more compelling, because our experience of cultural heritage is painfully brief. Why should we not take pride in the monuments once erected to the revolution of 1905, or to the victims of World War One? If not in reality, then definitely in the space of our thoughts, because as we watch some of the ongoing processes in our society it seems that our national – including cultural – self-confidence is lacking. This mythologised, symbol-saturated, perhaps also old-fashioned narrative form should be considered as a healthy reflection about the past, although an excessive leaning towards yesteryear can lead to stagnation. When one sees the great and sometimes also indiscriminate piety our cultural figures show towards our historical heritage and monuments, it stimulates ideas, worthy of witchcraft, of an encoded sense of guilt. As though culpability could travel in time and, through the present, attempt to downplay the fierce and obscurantist joy of burning down stately homes in the year 1905 that had taken over the Latvian farmer and labourer. An uncritical reverence for history elicits a counter-reaction, and one feels inclined to call on the slogans from the Futurist Manifesto that incited smashing museums and libraries to bits, and to overthrow “morality, all utilitarian and opportunist cowardice, and the coarse bourgeoisie”. Although we do not have any world class museums, despite the recently opened Riga Bourse, and the new building of the National Library just now shyly emerging on the Rīga skyline, a conservative and prejudiced society in the province is nevertheless also capable of obstructing normal development. | |

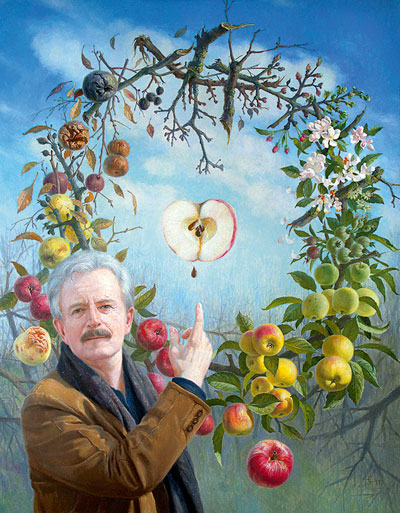

Imants Lancmanis. Self-Portrait on an Apple Wreath. Oil on canvas. 115x88 cm. 2011 | |

| But where does the recent accomplishment of Lancmanis, the Ābola stāsts exhibition, fit in with all of this? The retrospective of earlier works alongside the new ones graphically highlighted a change in the artist’s style: from a formal interest in painting techniques of the past, the synthesis of idea and form into a totality in The Fifth Commandment. Revolution and War to a fully conceptual exhibition like The Story of an Apple. Notwithstanding the different approach, Imants Lancmanis has remained faithful to a single principle: that of mimesis. The display of the latest works, as if in contrast to the earlier ones, is not shaped by the past or by history, but inspired by the direct, obvious reality of the artist’s surroundings: the apple orchards of Rundāle Palace. Unlike the painting series mentioned previously, Imants Lancmanis has eschewed any kind of synthesis, offering a series of colourful documentary photographs – a reportage on the lifecycle of an apple tree and apples as an allegory of human life: a tiny fragile bud, wildly beautiful blossom time, an awkward young “adolescent” – fruit, a ripe apple mature in self-confidence, and its tragic or natural passing away, leaving a bare branch for next year’s rebirth. This time all like-nesses have been directly transferred from nature; the artist’s contribution lies in his offer to view the stories of different apple trees and apples all together, thus bringing yet another opportunity to delve into one of his favourite subjects, as set out in the explanatory note to the exhibition – the ephemerality of life. Possibly the author of this text was under too powerful an impression of pictures seen as a child (in the past), still, when looking at the photographs on display, she was unable to escape a bothersome deja vu of images once seen in Soviet era books on apple cultivars. And the contemporary, spread out display of the photographs or spatial stimuli didn’t help either – heaps of this year’s apples and the little apple tree stuck in the middle. To convey the allegory, the showing of just one painting in an empty space would have sufficed: Pašportrets pie ābolu vainaga (‘Self-Portrait on an Apple Wreath’, 2011), incorporated in the invitation to the exposition. It depicts all the most essential things in the one place – the lifecycle of an apple, and the presenter of this old-fashioned, but by no means insignificant allegory, who invites us to engage with the rebus of meanings displayed. The self-image of an intellectual lord of the manor who involves all the people around him in a game leads one to suggest the following: that Imants Lancmanis’ most unique and conceptual work of art is his own life story, for which it would be difficult to find equal. /Translator into English: Sarmīte Lietuviete/ | |

| go back | |