|

|

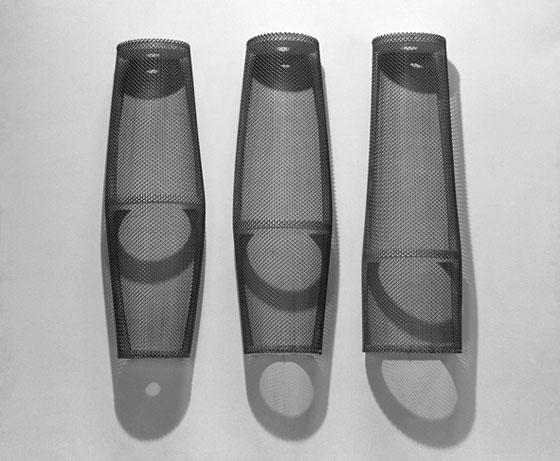

| Graceful wire netting Stella Pelše, Art Historian Collection of the Latvian Contemporary Art Museum: Kristaps Ģelzis. Three Graces. 1990 | |

Kristaps Ģelzis. Three Graces [Trīs grācijas]. Wood, metal. 1990 | |

| The ensemble of three wood and metal objects created by Kristaps Ģelzis, which has been given the title Trīs grācijas [‘Three Graces’] (1990), really does distantly remind one of variations on the diversity of proportions of the female form, including measurements ideal and not so ideal. “It is the art of nuance. It’s a question about overt and hidden form, about the poetics of form. It’s as if, right before your eyes, there is something quite real and trivial, yet also something a bit more. You could assume that nuance is the difference between two almost equal sizes. This difference is real and non-material. Maybe this time it’s the difference between an item as an exhibition object and the same item as a fact of reality, between the reality known from experience (a tree trunk, packaging, a woman’s body, hail) and its appearance in a different material.”1 This is how Ivars Runkovskis has commented on the subtle transformation of a ‘fact of reality’ (the titles of the works help give concrete expression to this) into abstract facts of art. The objects have been exhibited in Helsinki, at the Anhava Gallery (1991), as well as in Riga at the Kolonna Gallery (1992). Each object consists of a bent metal wire mesh, which is held by reinforced wooden bases fixed to the top and bottom. A wooden hoop has been placed somewhere around the middle part (at varied heights and differently shaped for each unit), thus creating different silhouette forms. The work displays an interest in simple forms (akin to abstract sculpture and minimalism) and the use of wire netting typical of Ģelzis’ art of the early 1990s (Stumbrs, [‘Trunk’] 1991; Valodas stunda, [‘Language Lesson’] 1992; Jāņa sēta, [‘Jānis Yard’] 1992; Sarkanais teniss, [‘Red Tennis’] 1994). A search for similar works leads us to the objects of American minimalist Robert Morris, for example, the steel mesh model Untitled (1967/1986, Washington National Art Gallery), in which straight angles are combined with streamlined curves, but the object, as the ‘occupier’ of three dimensional space, at the same time contains emptiness within it – inner space. In accordance with Morris’s conclusions, “simplicity of form doesn’t mean the simplification of experience. Unitary forms do not reduce relationships. They order them. If the predominant, hieratic nature of the unitary form functions as a constant, all those particularizing relations of scale, proportion, etc. are not thereby cancelled. Rather they are bound more cohesively and indivisibly together.”2 The name of Ģelzis’ work, derived from the well-known three beauties in Greek mythology, indicates an established subject in art history, confirming a connection with the issues of European cultural heritage. Historically, the range of interpretations of these beings extends from Renaissance classic masterpieces by Raphael and Sandro Botticelli to countless productions by salon academists on the theme of beauty. In its more contemporary versions, there’s no lack of expressive deformations and ugliness, but Ģelzis has supplemented this gallery of graces with structurally clear, tectonically laconic objects, which reincarnate the mythological images in an abstractly geometric and perfect, from the design aspect, dialect of 20th century art language. The artist himself has described this, his turn of the decade 1980–1990 preoccupation, as follows: “You can see there my new approach; I myself think that I tread a line between art and design. [..] In these works I no longer look at the idea, I look at the matter with the tips of my fingers. The idea comes right at the end and the work has to be pulled together with it. [..] But the mesh, just like a pencil, is related to the fact that by education I’m a graphic artist. The wire netting – it’s a grid. As soon as you bend it, it begins to develop form within its own structure, relationships between dark and light. I just love it.”3 The openwork, graphically expressive material has allowed Ģelzis to create simultaneously spatial and dematerialized shapes that give play to expressive chiaroscuro games. /Translator into English: Uldis Brūns/ 1 Runkovskis, Ivars. Formu mīklas jeb aicinājums līdzdomāt. Latvijas Jaunatne, 16 October, 1992. 2 Notes on sculpture by Robert Morris. In: Minimal Art. A Critical Anthology. Ed. Gregory Battcock. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995, p. 228. 3 Bankovskis, Pēteris. Nākotne ir džungļi. [Pēteris Bankovskis’ discussion with artist Kristaps Ģelzis]. Literatūra un Māksla, 23 October, 1992. | |

| go back | |