|

|

| The world of the Starn brothers Elīna Ruka, Photographer A conversation with Doug and Mike Starn | |

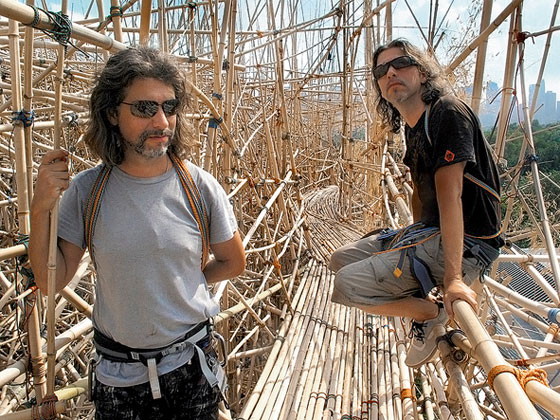

| Doug and Mike Starn live in the same world as the rest of us. It is light, history, culture, people and interactions on which their works, philosophy, growth and metaphors are based. Moths, snowflakes, trees, Buddhas and bamboos are just the visible images that speak about fleeting moments and thought processes, about all that makes up our individual personalities as well as all that we have in common or that makes us different. The identical twins were born in 1961 in New Jersey and have always been together since childhood, in thoughts and deeds. Their explorations in art and science have resulted in many exhibitions around the world. Their latest and possibly most ambitious work – Big Bambú: You Can’t, You Don’t and You Won’t Stop – is the microcosm of bamboo that grew on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art for eight months. This work is the quintessence of the artists’ philosophy about constant, unending change, about life and its meaning… and, ultimately, about each of us. | |

Doug and Mike Starn. 2010. Courtesy of artists | |

| Elīna Ruka: How would you introduce yourselves to a public that doesn’t know much about your work? Mike Starn: We are mainly known for photography, not traditional photography: it’s very large-scale, it’s constructive, you can see how it’s put together – it is made up of different sheets of papers and different mediums. Doug Starn: Conceptually, we are artists who work with the photographic medium. Our imagery lately has been nature-based. We have worked together our entire lives. E.R.: While browsing other publications, I noticed the level at which you complement each other – when one is missing a word, the other has it at the right moment. Do your ideas come to life as simultaneously as the words? M.S.: It’s the same, we have the same philosophy and we build ideas for our work together. E.R.: One of the ideas in your work is about the opposites that build a whole picture only by co-existing, as the individual within society, or a personal experience, or thoughts that can be understood by a larger group of people. Do these concepts stem from the fact that you are identical twins – the same, yet so different? D.S.: It’s an aspect of the world we see that, I don’t think, is appreciated so much – everything is the same, it is just different, that’s all. M.S.: Maybe our recognition of it does come from the fact that we are absolutely identical, yet we are different as individuals. The fact that we are meant to make up one whole, that’s something that runs through all our art – how everything is a part of something else and is made up of many things. It has always been at the back of our minds. E.R.: What are your inspirations? M.S.: It’s our own philosophy and our interest in science. D.S.: It has been formed by our interest in science – how the world works, how the cosmos works. It’s not so much as a social, psychological base, it’s really us trying to present our philosophies. But it’s not that we have a philosophy and then we think how we are going to outstrip this. It’s more an inspiration that comes for something we’d like to see and if we think about it, it always comes back to what our philosophies are and we then make the work stronger. E.R.: You have said that “the light is what controls every decision and action we take”. How literally should we understand this? Is the concept of light your philosophy? D.S.: This statement refers to our own private definition of what light is, it shouldn’t be taken literally. In many series of work that are sort of related, as Attracted to Light, Structure of Thought, Black Pulse light is the unifying factor, and light to us is everything – it is what you love and what you hate – these things guide us, whether we are conscious of that or not. Talking about the dualities that you were bringing up before, black is simultaneously the absence of light and the complete absorption of light, and that has always fascinated us. M.S.: It’s been a long time that we haven’t talked about these works on light, Big Bambú has been our preoccupation for two years now. E.R.: What needs to be achieved so that you would be emotionally and artistically satisfied? D.S.: This has been the most satisfying thing we’ve ever done! Why? I think partially because there is so much direct creation on a daily basis, it’s an artwork where you just keep coming back to it, adding and changing. M.S.: We are never satisfied with anything. We are always feeding it and making it grow, that’s the joy. It feels like it’s loving you back. D.S.: It’s been such a joy – we always enjoy making art, but nothing has brought us such joy as this piece. | |

Doug and Mike Starn. Big Bambú. Installation. Fragment. 2010. Photo: Elīna Ruka | |

| E.R.: Please tell us more about Big Bambú. D.S.: It was conceived to speak more clearly about the way all of our work is, how everything is made of many pieces that continually... M.S.: ...affect each other and allow something else to be brought in, nothing is ever finished. D.S.: People are always approaching it in a new way, so it becomes something new through those ideas, whether it’s you or it’s a city, or culture or your family. The conglomeration of parts would allow the next part to be added to it. The original piece we wanted to do also included an arch that stretches out as far as it can, representing possibly a moment when you don’t really know where it’s going. So it reaches out as far as it can and then drops down to the ground, and then the piece is dismantled from the back in and fed through... M.S.: ...through the artery system to the front and continues to grow through the space. Here we couldn’t do that, so we decided to work with another motif we’ve used many times – that something is the same, but always becoming something new – a seascape! It’s always in motion – it’s always the same, but never the same. That’s what we all are. E.R.: Did you have a clear image of how Big Bambú should look right from the beginning? D.S.: It took us a couple of weeks after the MET had asked us to... M.S.: ...come up with the idea for them, when we realized that the seascape was the one. Then we started to build a model, so we had a general sense of what the scale would be. D.S.: But there is a lot of chaos that enters in every day – we are working with between ten to sixteen rock climbers to make the piece, and we give them tremendous freedom, that’s how the piece is full of life! We give them certain ideas of where they should go with the piece. Maybe we want lots of pieces to go in one direction to add a certain energy flow. We have to keep the chaos. E.R.: You’ve been building the first Big Bambú in your studio at Beacon – is the experience different here, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art? D.S.: Yes, both better and worse. Here it’s not as free, we need to worry about the public, their safety, the piece had to be constricted somehow in its footprint, while in our studio it’s constantly growing and the forward momentum is a real thrill. The positive side of working here – in New York City, in Central Park... M.S.: ...and with the Metropolitan Museum of Art – it has one of the greatest collections in the world – to be here is unbelievable! D.S.: We’ve been here every day for eight months now, working on this piece, and the positive side is also the public. It’s great to have people enjoying it. And just being in the sunshine is incredible. E.R.: How much do you think of such concepts as time and space within this piece? D.S.: The piece is constantly changing. M.S.: It’s really one of the mediums of the piece... D.S.: ...and we document that in our photography of the piece. We wanted to do a time lapse and to photograph it on a daily basis, but unfortunately we didn’t have enough money for that, so we have bits and pieces, though not the whole time lapse. M.S.: That element of the growth of the piece, I wish that it could be looked at, so you could get the idea of time and space changing. | |

Doug and Mike Starn. Big Bambú. Installation on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 2010. Courtesy of artists | |

| E.R.: What can people experience through your photographic artwork of Big Bambú? D.S.: I think we take some pictures that help to relay some of the life of the piece and the life of the builders... M.S.: That’s the social aspect of the piece. D.S.: To us, these pieces are organisms, and Mike and I and the climbers are part of that organism, we are just the agents within the organism that allow it to move about and grow. M.S.: I think it’s really important to have these pictures to get the sense of the activity; and the videos as well. E.R.: Can Big Bambú be finished? D.S.: It’s a series of works. We are not just making the one, so a piece can be finished, I guess... M.S.: When it’s over, you can put it away and it’s gone. E.R.: Because there is a limit in time... D.S.: Yes, we would love to continue... M.S.: If we could set up one in the studio with the funding and just go on, even long after we’re dead, that’s our goal. E.R.: Your works are simple from the outside, yet complex in their ideas and execution. Many people, though, see them only as beautiful, not understanding the depth in them. Do you think the work loses anything in this omission? M.S.: A lot of people don’t recognize what’s in it, they are not willing to see more – they see something beautiful and don’t think that there could be something else. It’s in there, some people see it by themselves, others need some background, and there is nothing wrong with that at all. D.S.: There are enough people who seem to understand and get a lot out of it, we are lucky and just continue to do what we are doing! E.R.: Your work for me is like a text where every word is in its right place, nothing too much or too less is said. Have you ever felt that by stepping one foot aside everything could go wrong? D.S.: It’s tricky, you just need to watch what you are doing! M.S.: There are times when the climbers would take it in that wrong place and we would need to undo and redo something, so that everything happens the way we wanted to, but that’s with not too much control. In our other work, there is a certain amount of freedom and looseness, and we know how and when to rein it in. E.R.: Do you have any unfinished projects or ideas? It seems that no matter what, you stubbornly try to find a way to succeed. M.S.: We are pretty determined about our goals, we just know that everything is possible. There are lots of projects that we have in our minds that we haven’t gotten to yet because of either money or time restrictions. E.R.: What are you planning after Big Bambú at the MET? M.S.: It will take us a few months to take it down and then we will continue to work on our photographs and the videos we’ve shot here. D.S.: We are also working on smaller sculptures, based on Big Bambú, and then we are working on plans to take this project to other cities and other countries. | |

| go back | |