|

|

| Is it easy to be caught between “Sunday artists” and commercial kitsch? Alise Tīfentāle, Art Historian Rauma Biennale Balticum 2010 What’s up, Sea? – Contemporary Art of the Baltic Sea Region 12.06.–19.09.2010. Rauma Art Museum | |

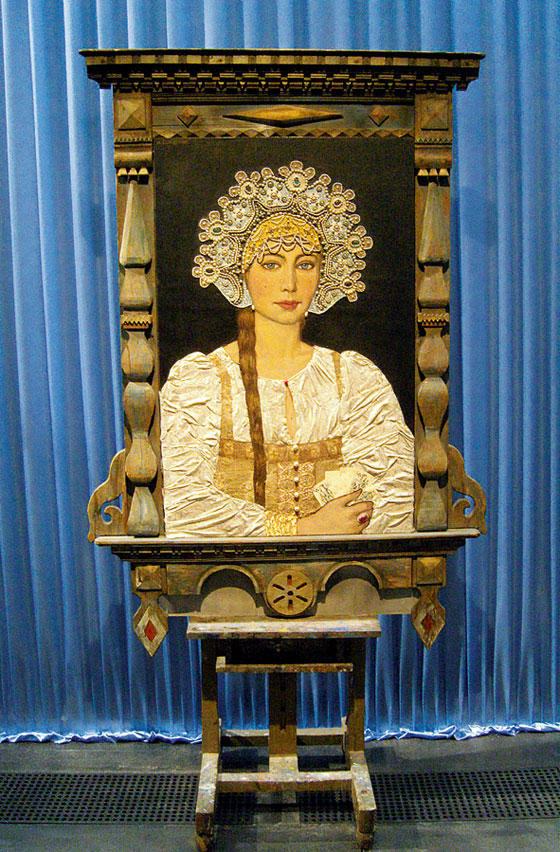

| While travelling from Riga to Helsinki, from Helsinki to Turku and then on to Rauma to see this year’s Rauma Biennale Balticum, what I saw at the various stops combined to present a vision of the future of art in Latvia. The participation by Latvian artists in a few respectable international exhibitions is a sign that artists in Latvia are working, creating and thinking. But one question remains uncertain – is there any rational foundation, here and now, for being an artist? Scenarios for the future of art in Latvia The exhibitions seen in various cities of Finland in late August seemed to be almost prophetic. Kiasma, the Helsinki contemporary art museum, presented an exhibition of Ilya Glazunov (born 1930), the Russian painter and portraitist.(1) The lavishly set out exhibition Ilya Glazunov and Finland shamelessly demonstrated a peculiar kind of kitsch: portraits of the Finnish elite from the 1970s by the Soviet artist, which stared at the viewer quite like illustrations of a fairy tale book. (The exposition commentary did refer to the traditions of Byzantine and Old Russian visual art.(2)) The president of Finland, the creator of the designer brand Marimekko, politicians and prominent figures in cultural life. One can only wonder about the taste of these people, who after all should have favoured subtly nuanced greys and generally all that is Nordic. Halfway between Helsinki and Rauma is Turku – the European Capital of Culture 2011. In the contemporary art exhibition hall of the private museum Aboa Vetus & Ars Nova, there was an exhibition of European naïve and folk art Not to be Framed. In its own way this exhibition connected the appearance of Glazunov in a respectable contemporary art institution with the solitary and as if counter-current course taken by the Rauma biennale. The exhibition of naïve art was prolific with various creative solutions for art in conditions of “no budget at all” – art can make good use of second-hand materials and household items; handicrafts, assemblages and collages were also widely represented. A commentary on the exhibition pronounced: “Contemporary folk art … is based on a need to create and the will to make art rather than financial benefit or trying to fit into the practices of the art world. Contemporary folk artists aim to develop their expression without boundaries or models.” Art as a hobby, the phenomenon of “Sunday artists” and the creation of art in the name of Kunstwollen or the ‘will of art’(3), not as a professional career – this is one of the scenarios for the future of art and art theory in Latvia. If Latvia cannot afford professional, non-commercial art and art theory, then art must become a hobby. Artists and art theoreticians must be able to produce something worthy of consideration (but at a low cost, of course) twice a year when there is a mass demand for their profession (at Museum Night and the White Night). The rest of the time they have to do something else. Or they must become glazunovs of a sort. | |

The naïve and folk art exhibition 'Not to be Framed' at the museum Aboa Vetus & Ars Nova, Turku. View of the exhibition. Photo: Alise Tīfentāle | |

| Cultural policy of the periphery The Contemporary Art Biennale of the Baltic Sea Region in Rauma has been taking place since 1985. As artist Franceska Kirke neatly pointed out in 2002, “the existence of a biennale in a small city like Rauma is a cultural phenomenon”(4). The conception of the biennale could be in a way likened to the obsession of the main hero of Werner Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo, because Rauma is a small provincial town in Finland – an ethnographic museum, a UNESCO culture heritage site, not a citadel of contemporary art. This is not where contemporary art is created – at least not on such scale and with the same infrastructure as in the big cities.(5) But why shouldn’t art be viewed here? And it is exactly the odd location (Rauma cannot be visited “on the way”, you have to plan a visit there) that adds distinctive character to the biennale. Even a search on Google brings nothing of consequence about the biennale, and the web site of the Rauma Art Museum gives only the scantiest minimum of information: a press release, the names of the artists and information about museum opening hours. But already in 1994 Helēna Demakova, the curator of the Rauma biennale, pointed out that “such a widely varied collection of images removed from their creators tends to produce an unusual atmosphere. These images have nothing to do with the aspirations of the policy-makers or the ambitions of those marketing the exhibition; they are part of life, including both the profanation of notions and the fuss of public relations”(6). The regional principle, which the biennale is based on, and the fact that the location is far away from any cultural Grand Tour, can be in a way related back to the status of our (chiefly – the three Baltic states) art in a world context. Of course, “our” art gets to galleries in London and New York, it can be viewed in the biennales of Venice, Moscow and Sydney, and at times it ends up in private collections in wealthy countries. Yet only in this remote place, as seen from the egocentric point of view of Western Europe, in the quiet and peacefulness of the seaside provincial town, “our” art is really at home. Historically, the work of the curator has played a significant role in the creation of the image and reputation of the biennale. Ten years ago Ieva Auziņa remarked in her review of the 2000 Rauma Biennale Balticum: “Being aware of the Finnish provincial charm of Rauma, discarding unnecessary ambitions and respecting tried and tested values, I have to admit that this tradition, with origins in the mid-80s, has justified itself; one only has to look through the catalogues of the previous exhibitions in Rauma to be able to make relatively precise indents in the art of the recent decades. ... The conceptual direction of previous years formed by curators such as Barbara Straka, Helēna Demakova and others have been successful.”(7) But since 2002 the Rauma biennale has been curated by a single team – chief curator Janne Koski and Henna Paunu. And however topical and promising the themes of biennales of the last decade may have been,(8) the tagline of this year’s biennale What’s up, Sea? left some suspicion that the ideas may have dried up and that there has been a return to a tradition which is all too familiar from the Soviet period. A declarative “unity of the nations” and the gathering of creative collectives for thematic events from the series of By the Amber Sea, Man and the Sea and The Amber Land cannot in any way be associated with a meaningful and substantial unified concept. In keeping with the title of the biennale, the curators had chosen works which directly or indirectly feature water, and where the sea is depicted either in a realistic or figurative role. It has to be admitted that the “theme” of the exposition relates only to the formal side of the works, the criterion being the presence of the water, or sea (as image, concept or material). | |

Kaspars Groševs, Darya Melnikova, Rūta Kiškyte. The Island. Installation. 2010. Rauma Art Museum, publicity photo | |

| ‘Man and the Sea’ in a contemporary interpretation One of the most powerful works at the biennale was the video installation by Sergey Bratkov (Russia) Balaklavsky Drive. The loop consists of a black and white film clip of boys jumping into the water, one after another, from a military or industrial-looking embankment. The clip is accompanied by a pop song. In front of the screen in the darkened room there are reinforced concrete blocks with menacingly raised fragments of a metal carcass. “To make his soldiers brave and prove that the British cannot shoot during the Battle of Balaclava a hundred and fifty years ago, Ensign Demidov climbed on the parapet and strolled in full view of the enemy trenches with a cigarette in his lips. In my movie Balaclava boys enthusiastically leap into the water of the bay packed with metal. I’m scared: their life is in danger. But I envy them. “To live a beautiful life and die young” is what I wasn’t able to do,”(9) says the artist. Nostalgia for the recklessness and adrenalin which can only be justified during teenage years, dressed in the form of rough concrete, a catchy pop song and the black-and-white video, aptly and in a Freudian spirit synchronise the libido with the death drive. Miks Mitrēvics also took part in the biennale with the installation Fragile Nature. An open window with curtains floating in the wind, outside the window a beach scene with a couple embracing, watching the sunset – we could say that the work has been developed and modified from those means of expression and characters which were part of the Fragile Nature exhibited in the Venice biennale. Just as in Venice, in Rauma too, the spatial installation was supplemented by a video camera, which in an adjoining room broadcasted live the instant movie from the intricate “set”. A spatial installation was also presented by Kaspars Groševs, Darya Melnikova, and Lithuanian artist Ruta Kiškyte in a joint work The Island. An isolated room filled with small surprises, sound and light effects, reminiscent of the deserted rooms in computer adventure games (usually in these rooms you can click on an object to find a “first aid kit” or a “life”, a useful “weapon” or, quite the opposite, wake up an evil force in the adjacent room). The authors, commenting their own work, stated: “It is about doubt and obsession and the combination of the two (Kaspars). And aging (Ruta). It is our vision of devotion and hope as well (Darya)”.(10) Like it or not, this work gets compared to Mitrēvics’ Fragile Nature. Possibly there are more differences than commonalities, but in a small-scale exhibition like this, one firstly notices the analogies of the means of expression (a spatial installation, the composition of small details, the use of various “temporary” solutions, lighting effects and even similar piles of sand). The staging of small details with a multitude of meanings could be referred to a film set, a stage set of a theatrical play, or a scene from a dream; its possible interpretation does not become overbearingly declarative and doesn’t intrude with a narrative. Laura Stasiulyte (Lithuania) participated with an unpretentiously displayed work– a wordless documentary coverage of the absurdities of daily life called Getting off. A huge cruise ship pulls into the port of Klaipeda, and a crowd of Western tourists of a respectable age get off. It seems that they have no idea (and don’t even want to have any idea) where they are and why they are there. They move around the specially organized bustle of the port: girls in folk costumes selling craft items, a folk music group, and sellers of trinkets, all desperately hoping they will be able to sell something to the passengers of this ship. Abstracting ourselves from contemporary reality, we can imagine that this is how the indigenous people might have appeared to the eyes of the interlopers from Spain and Portugal a few centuries ago. There is a desire to avert one’s eyes with a certain feeling of shame, as it seems that the whole of Eastern Europe is infected with the self-image of being exotic aborigines, and to a large extent many of our “cultural events” are held with the hope that a well-off Western European citizen might throw a coin into our hat, moved by the zealous kokle playing or tempted by our jāņusiers [traditional Latvian cheese]. It is a proper discourse of colonialism (without any prefix of post-), which we ourselves happily promote. If someone in Riga doesn’t think so, then have a read, for example, of newspaper reports about the visits of the deputies of NATO Parliamentary Assembly to the Latvian countryside this [last] summer: “…the delegation visited the restored part of the castle, in the courtyard viewed handicrafts made by local craftsmen, and enjoyed a performance by a medieval dance group. … A parliamentarian from Bulgaria said that both castles are attractive tourist objects. He had viewed the works of the craft artists with interest, but didn’t buy anything. … The traders set up their booths around 1 p.m., the guests arrived shortly before 4 p.m. The long wait in the damp weather was not pleasant. The foreign visitors had not been planning to buy local production.”(11) | |

Ilya Glazunov. Russian Beauty. Oil on wood, collage. From the collection of Amer Sports Oyj. 1968 | |

| The work Loop by the Polish artist Julita Wójcik attracted attention with its witty and irrational idea. A procedural art work has been documented on video – a ferry trip from Gdynia in Poland to Karlskrona in Sweden. By the request of the artist, the ferry makes an unexpected change in its route and during its otherwise straight course completes a loop in the middle of the Baltic Sea, thereafter continuing on to its destination in well-behaved manner. The theme of biological-technological politics in art, as has been particularly topical in recent years, was demonstrated by the Finnish artist Tapio Mäkelä in cooperation with M.A.R.I.N. (Media Art Research Interdisciplinary Network). The installation Blue Green was a container of seawater in the shape of the Baltic Sea, with blue-green algae (cyano-bacteria) growing inside the tank. These algae are indicators of the level of pollution in the sea, and are also considered to be the first life form on Earth, producing the oxygen necessary for the formation of the atmosphere. The authors indicate that the harmless activity of growing algae poses an important question: “Would this transformation of the Baltic sea into a pool of biomass in the name of green energy be ethically questionable?”(12) The biennale has a retrospective character – the exposition embraces approved, tested values. Although this biennale would not be the first place where Budak or Obrist or any other high-profile curator would come to in search of new and earth-shattering art, the Rauma biennale and taking part in it is important to each of its participants and, of course, significant also for Latvia as a country belonging to the cultural space of the Baltic region. The organizers of the biennale have in good faith fulfilled their mission of gathering and displaying quality art, which has been created right here, on the shores of the Baltic Sea, and the participation by Latvian artists adds to the composite portrait of the Baltic region. It is, in a way, a symbolic exhibition, which at the level of feelings speaks of our detached, slightly distant and separate space (although it all depends on which reference point should be considered the centre). The three Baltic states and Finland share an agrarian history with a rapid involvement into the processes of Western cultural and intellectual life in the 19th century. Here this common background manifests itself as the cultural-historic backdrop (roots) of Rauma, on which the seemingly out of place flower of contemporary art has blossomed. The author of the article would like to extend her thanks to the Nordic Council of Ministers for assistance granted under the auspices of the Nordic-Baltic mobility programme which made it possible for her to visit Finland. (1) It was followed by a rather conventional exhibition Sour Cream, addressed to a wider public with the works of YBA from Finnish private collections. The byline Hurst and his Contemporaries says it all. 10 September–7 November, 2010. (2) Vanhala, Jari-Pekka. Who recalls Glazunov? Kiasma Magazine, 2010, No. 45, Vol. 12, p. 13. (3) A term used by art historian Alois Riegl in 1893. (4) Kirke, Frančeska. Rauma Biennale Balticum. Studija, 2002, No. 25, p. 48. (5) While in Rauma, I was looking back at one of the most important art events in Latvia, the Cēsis Art Festival, and with the distance of time and space I realized that I disagree with the statement made at a conference during the festival that it is necessary to attract local artists who live and create work in Cēsis. (6) Demakova, Helēna. Sapnis vasaras naktī. First published in Finnish and English in the catalogue Rauma Biennale Balticum ’94 (Rauma: Rauman Taidemuseo, 1994, pp. 11–25). Quoted by: Demakova, Helēna. Citas sarunas. Riga: Department of Visual Communication, 2002, p. 120. (7) Auziņa, Ieva. Rauma Biennale Balticum 2000. Atgriežoties nākotnē (Retracing the Future). Studija, 2000, No. 5, p. 30. (8) For example, Basic Elements (2002), Talking to Me? (2004), Wake up! (2006), Flower Power (2008). (9) Rauma Biennale Balticum 10. Rauma: Rauman Taidemuseo, 2010, p. 25. (10) Ibid, p. 37. (11) Auzāns, Vilnis. NATO parlamentārieši iegriežas arī Bauskā. Bauskas Dzīve, No. 62, 2 June 2010, p. 10. (12) Rauma Biennale Balticum 10, pp. 48–49. /Translator into English: Vita Limanoviča/ | |

| go back | |