|

|

| The Worker, the Kolhoz Woman, a Granyonka and the Freedom Monument Zane Balčus, Cinema Specialist Film Versija Vera by Ilona Brūvere (2010) | |

Still from Ilona Brūvere's film 'Versija Vera'. 2010 | |

| Director Ilona Brūvere, in the introduction to her film Versija Vera (‘Version Vera’), describes it as a documentary play, whose main heroine is the sculptress Vera Muhina. The textual material has been developed from her diaries and the film’s authors have synthesized Muhina’s personal notes and publications, creating a version about the Riga-born artist who was prominent in the Soviet Union. In the film, one can hear Muhina’s thoughts against the background of scenes on Red Square and the church massacres taking place during the civil war in 1920: “We live in heroic times. I don’t think that art can reflect the reality of life. It simply isn’t possible, otherwise it would be naturalism. Art speaks of dreams and ideals.” Muhina found expression through the canon of socialist realism. Through Ilona Brūvere’s perspective, Muhina’s main sculptural work, the 34 metre tall statue ‘The Worker and the Kolhoz Woman’ which stood out for the USSR at the World Exposition in Paris in 1937, has gained subtlety and a poetic tone. ‘Versija Vera’ is not a traditional documentary portrait of a famous figure. At the beginning of the film, [actress] Kristiāna Dimitere is introduced as the stand-in for Muhina. The film is in black and white, and the visual material is made up of staged productions and cinema newsreels of the time, in a few of which Muhina and her works are shown, but the greater part serve for the por¬trayal of a particular historical period. Photo materials aren’t used, the pictures are in motion, only at times they have been given a “living picture” (tableau vivant) aesthetic. The relationship between the visual solution and the offscreen text develops in a number of forms. Associations generated by the text are intensified through images. The adolescent Vera, listening to the music of Wagner during her holidays, voices a longing to see Feodor Chaliapin performing at the Munich Opera. In the documentary sequences a train slowly moves along a railway bridge across a river. The camera is placed at the front of it, but Chaliapin’s voice can be heard in a song. The rhythm of the journey links up with the emotional girl’s aspirations for the longed for event, pervading the episode with a mood charged with expectation. The reinforcement of the contrast is made by the destruction, through the spoken word, of the associations called up by the image. When Muhina is studying in Paris, the street musicians and dancing sailors who are also caught in documentary scenes symbolize the easy nonchalance of the bohemian city. At the end of the scene a voiceover announces that in Muhina’s life there isn’t much recreation, only work – lessons in the morning and the evening, but her free time is spent in the sculpture halls of the Louvre, which are also depicted in the staged episode that follows. | |

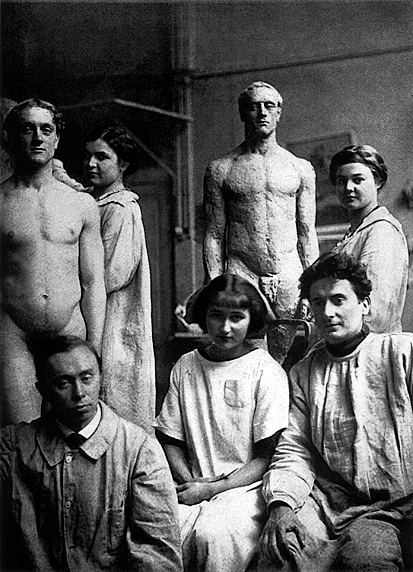

A group of Russian artists in the master workshop of sculptor Emile Antoine Bourdelle, pupil of Auguste Rodin. Second row, first on the left: Vera Muhina | |

| The choice of black and white material in the filming of the staged episodes was so that they could be aesthetically matched with historical newsreels, the perfect depiction of contemporary film being imparted with a grainy effect. The use of this technique is a step towards imbuing an “aged flavour” to the portrayal, but it is only one of the elements which differentiate the historic sequences from those created today. The newsreel images are not homogeneous, and have a flickering quality. The authors have attempted to reduce the perfection of the produced images with lighting. The sources of light are frequently placed at the back of the scene, creating distinct light and dark areas and imparting a hazy quality. The contours of the figures in them become less clear, the heroes played by the actors – more conditional. This conditionality is powerfully revealed in a number of “live picture” productions. The theatrical technique where actors or models stay motionless in studied poses is used in the theatre, in photography and in early cinema also, as demonstrated in the creative works of French cinema pioneer Georges Melies. Restricted by censorship, representatives of English theatre in the 1920s and 30s incorporated nude actors in their performances in this way. In ‘Versija Vera’ the tableaux vivants appear in episodes taking place in artists’ workshops, where Muhina first of all masters drawing, and after that, sculpting. In Ilya Maskov’s drawing lessons, a nude model is the centre of the scene, with three students in the studio working on their sketches. The only one moving is Maskov. There is an episode in Paris constructed nearly identically, in Emile Antoine Bourdelle’s class, where students stand around a male model, but Bourdelle is moving about the room. This technique is used not only in relation to art and nude models, but is included also in episodes in a hospital, where Muhina has ended up after an unfortunate tumble with a toboggan. The patients here are motionless, and doctors and nurses move among them. In her films, Brūvere refers to her experience in surrealistic art. Here there is a brief but very striking episode, in which the twenty year old Muhina suffers in an accident in winter, riding down a hill on her toboggan. A crystal ball, a wheel and other visual elements interchanging with each other, the increasing speed and the rhythm of the music warn of the impending crash. In its rhythm and intonation, the episode has something in common with Fernand Leger’s 1924 work ‘Mechanical Ballet’. The film’s progress is determined by the chronological division – with an intervening title showing the year in which the next episode takes place. Such a structure could easily be¬come repetitive, but the authors have been able to overcome this to a large degree with the variation of visual techniques. Knowing but one fact about Muhina’s creative work, in the linear narrative the year 1937, specifically, seems to be the film’s culmination. | |

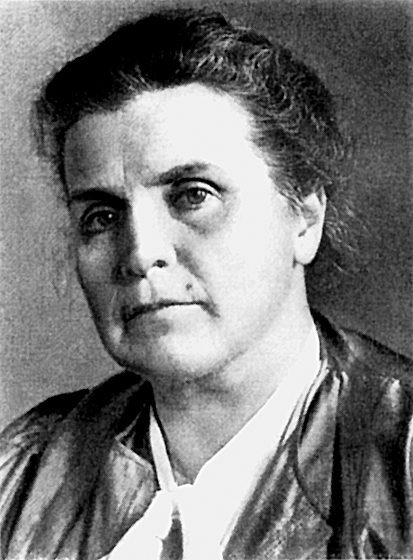

Vera Muhina | |

| Muhina herself appears for the first time in the film in the documentary scenes from the World Exposition in Paris. She supervises the assembly of the sculpture, the parts of which have been transported from Moscow in 28 train carriages. “The worker is not a model of historic truth, but a symbolic and imaginary image created by an artist, depicting the ideal of the era,” is written in Muhina’s diary. Her image – a complete, powerful woman – contrasts with the comparatively fragile build of Dimitere. In the dramaturgy of the film, this is the precisely moment after which the visual experiments slacken off. Muhina, as documented in the newsreels, is often included in the film, which, it seems, prevents the authors from constructing their vision about events with the same sort of creative verve as before. In addition Muhina’s creative work in the 1940s and the beginning of the 50s until her death in 1953 wasn’t that successful, and due to Stalin’s regime her hopes remained unrealized. The film preserves the myth about Muhina as the designer of the granyonka glass [a ribbed Soviet era glass]. The artist’s journey to Riga to help save the Freedom Monument, shortly after the conclusion of the Second World War, is also mentioned. The blending of documentary and art cinema principles is an inseparable part of Brūvere’s creative output, as can be observed both in her earlier works, as well as in the recently made short films Gleznotāji (‘Painters’) and Stacijas (‘Stations’). In those the staged scenes are minor stylistic additional elements, however the greater part of the film’s visual material is built on them here. Brūvere’s unorthodox approach to the portrayal of the person featured in the documentary is echoed in the film’s textual material: it is a personal Muhina monologue and Brūvere’s personal visual interpretation of Muhina. ‘Versija Vera’ is among the best film documentary portraits in Latvian cinema of recent years, a category in which searches for unusual forms of expression can be noted: ‘Valkyrie Limited’ by Dāvis Sīmanis (about Viesturs Kairišs), ‘Klucis – the Wrong Latvian’ by Pēteris Krilovs (about Muhina’s contemporary Gustavs Klucis) and others. /Translator into English: Uldis Brūns/ | |

| go back | |