|

|

| Practice is more important than Theory Alise Tīfentāle, Art Historian Izstāde Exhibition Look How Nice!? 11.02.–14.03.2010. Creative workshop at the Latvian National Art Museum | |

| Before I went to see this exhibition, there was yet another active exchange of opinions in the editorial office about a curator’s functions and capabilities. Adam Budak, once interviewed by Studija, and other curators of the great biennials and triennials were invoked, finally concluding that we do not have a single young curator of contemporary art who, with their intellectual commentary, could expand the field of understanding of an art work. Perhaps now we will have somebody? To start with, it should be noted that the exhibition takes forward the cooperation between the Art History and Theory Department of the Latvian Academy of Art (LMA) and the Latvian National Museum of Art (LNMM), and this is the eighth year running that future art history graduates from the LMA practice working as curators and present an exhibition of works from the LNMM holdings. Paradoxically, the exercise is carried out applying practical knowledge mainly acquired auto-didactically: the purpose of the LMA bachelors’ programme in Art History is by no means to “produce” curators of contemporary art, but rather art historians who are destined to work in a museum or in archives. Hence the initiative of the budding bachelors to engage in current art processes is a kind of a leap into the unknown. The idea of the exhibition belongs to the project coordinator Šelda Puķīte, and the team of curators includes Nils Ārens, Iveta Damroze, Inese Kundziņa, Anna Kustikova-Veilande, Inga Litvina, Ieva Muceniece, Līva Mišele Piešiņa, Alīna Zubkova. Puķīte builds her idea around Soviet period works from the LNMM collection (the artists are Auseklis Baušķenieks, Līze Dzeguze, Alberts Goltjakovs, Imants Lancmanis, Jānis Pauļuks, Maija Tabaka) and a reading of them from a contemporary viewpoint. The crux for the interpretation is a search for signs of potential consumerist culture in Soviet period art. | |

Imants Lancmanis. Still Life. Oil on canvas. 45x51cm. 1969 | |

| As a complement, the curators have invited young artists (that is those who have recently graduated or are still studying at the Academy) to produce “remakes” (the term used by the curator team, but to my mind “paraphrases” would be a more accurate description,) of the Soviet time pieces. The young artists (Anna Kustikova-Veilande, Svens Kuzmins, Maija Mackus, Elīna Poikāne, Lāsma Pujāte, Krišjānis Rijnieks, Magone Šarkovska) could choose an inspiring work from the list the curators offered, and, expressly for this show, produce new works on the same theme. The introduction to the exhibition explains that “the exhibition highlights the issue of people’s craving for a product and its impact on a society’s ideals. The project proposes to assess the different ideologies of a consumer society under capitalist and socialist systems, and to evaluate the picture in Latvia, both when it was in the Soviet Union and now as part of the European Union”. It can be said that the curator team have created a miniature art event – the confrontation of art from two eras, a clash or interplay of differing paradigms. Only the theoretical justification about the possible presence of consumer culture and its criticism in Soviet art did not seem to be the most convincing element of this exhibition. Every piece of the Soviet art on display was subject to interpretation: the art history bachelors in the making offered their version of the work as a concise annotation. The young artists invited to participate, meanwhile, interpreted and explained their own works themselves. This was either an inconsistent approach to the materials on the part of the curators, or else the declaration of a particular attitude. A Soviet artist should keep silent, and let the art theoreticians do the talking, but as usual the interpretation of contemporary works is entrusted to the artists themselves. | |

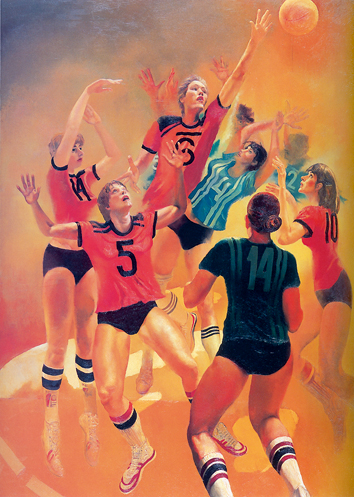

Maija Tabaka. Basketball. TTT. Oil on canvas. 231x165cm. 1980 | |

| This rather unjustified allocation of privileges was further under-scored by a detail such as the portrait photos accompanying the young artists’ comments on their works, yet missing in the commentaries on the Soviet era works. Thus these artists were featured in the exhibition not only as “silent” but also literally “faceless”. The curators had as if split the responsibilities: their competence was the selection of historical material and its verbal interpretation, as well as the choice of the young artists who did the periphrases. The result itself – the young authors’ works and the interplay of their creations with the works from the museum collection – remained outside the curators’ competence. It must be borne in mind that the project was implemented under laboratory conditions: the long standing co-operation between the LMA and the LNMM; the work was carried out under the academic supervision of Andris Teikmanis (LMA), Andris Vītoliņš (LMA) and Diāna Barčevska (LNMM). Nevertherless, even under such favourable conditons, some practical details have been left unattended to. For example, it would seem a given to prepare the annotations also in English, and likewise to include a list of the curators’ names on the exhibition poster (because a part of a successful curator’s career is also the visibility of one’s name and brand). The promised theme unfolds mainly in an illustrative manner: the exposition revealed the declarative and, more often as not, formal way of thinking (that is, skating “on the surface”, as termed by philosopher Maija Kūle), as is typical for our time. The paraphrases by the young artists were rather one-dimensional, mostly playing around with the subject matter aspect of the Soviet period works and transposing that into a seemingly contemporary language of artistic expression. The newlycreated pieces are to be appreciated only in the context of their source of inspiration, and cannot be imagined displayed as independent works without being linked to the respective work from the Soviet period. Still, it could be interesting and even fascinating for the viewer to observe the “migration” of motifs and their “second life” in the works of contemporary artists (and providing such an opportunity is to the credit of the curator team). For instance, Maija Tabaka’s (b.1939) painting Basketbols. TTT (‘Basketball. The TTT Team’) and its paraphrase by Maija Mackus (b. 1982) – a linocut Sportiņš (‘A Little Sport’). Art historian Iveta Damroze justifies the inclusion of Tabaka’s painting in the exhibition due to its subject matter: “For the Soviet Union, sport was a propaganda tool for the cultivated gloss of the Soviet superpower in its political rivalry with other countries, the U.S. in particular.” Further on, Damroze ac-centuates that the painting features the TTT team: “Latvian women basketball players played out the distinctiveness of their nation”, and sport is discussed as “a product of Soviet consumerist culture”. The linocut by Mackus features bunnies (in a remotely similar tonality and composition). The artist alludes to a media item about “a woman athlete of Latvian origin who has made it to the list of the world’s top ten sexiest sportspeople”, and adds: “More bunnies for sport!” Tabaka’s painting shows the heroisation of the image of a woman-athlete, at the same time retaining the surreal ambience inherent in her art (where else do we find that expanse imbued with golden light in which the basketballers are levitating?) and an eroticised atmosphere. What Tabaka’s painting conveys by pictorial means, is verbalised in the annotation to Mackus’ work. For example, the vulgarisation of modern popular culture, forming an association possible only in a patriarchal and chauvinistic society – that of “a bunny girl”, therefore, a man’s hunting trophy and an object of enjoyment, in addition to all other connotations related to the image of the hare in folklore and the qualities of the hare as an animal. The author is slightly ironic about this patriarchal point of view, and has selected Tabaka’s subject as a vehicle for her own irony; still her attitude towards Tabaka’s painting does not extend beyond this formal allusion. | |

Maija Mackus. A Little Sport. Linocut. 50x41cm. 2010 | |

| A wood sculpture by Līze Dzeguze (1908–1992) Sieviete ar kūli (‘Woman with Sheaf’, 1945) is in dialogue with the graphic art piece Rupjmaize (‘Rye Bread’) by Lāsma Pujāte (b. 1984). In her interpretation of Dzeguze’s work, art historian Inese Kundziņa states that “the subject dictated by the authorities interacts with the artist’s own vision of the world, which has taken its visual form in wood. Good natured and naively truthful, the image created by the artist has found its decoding with the passing of time: the Soviet Union merely created a myth of happiness.” In Pujāte’s graphic work we come across a part of the modern myth of happiness: it seems quite logical that the contours of Dzeguze’s sculpture have become a decorative image on the wrapping for industrially produced rye bread. Another sculpture by Dzeguze – Virs plāna (‘Exceeding the Plan’, 1952), has been analysed by Ieva Muceniece. Like Kundziņa, Muceniece also has stressed differentiation between the subject of fulfilling the plan, ever-present in the “catalogue of themes” of socialist realism art, and the “unpretentious charm” of the piece itself. Svens Kuzmins in his painting Eko-Plāns (‘Eco-Plan’) has relocated the subject of Dzeguze’s sculpture and presented it with a global glossy magazine aesthetic. Šelda Puķīte’s interpretation of Imants Lancmanis’ (b.1941) painting Klusā daba (‘Still Life’, 1969) with “imported” tinned fish may arouse discussion. In this work, Puķīte has discerned the presence of an “inverted pop art” motif, referring to similar themes in works of American pop art. The similarity, however, is only superficial. The derivative by Magone Šarkovska seems less intriguing than the interpretation– her painting Augļu dārzs (‘Orchard’), in which she comments on the subject of Lancmanis’ painting. (“A major shortage creates tendencies: in Soviet times, they were imported goods, currently – an eco-lifestyle and criticism of consumer society,” writes the artist in her commentary). | |

Magone Šarkovska. Orchard. Oil on canvas. 60x50cm. 2010 | |

| The painting Ceļš kosmosā (‘Journey in Space’, 1981) by Alberts Goltjakovs (b.1924) might be more likely to remind modern-day youth of Hollywood science fiction or an ad for a computer game, rather than propaganda for Communism (which may even be irrelevant, as in both cases it is propaganda and mind programming). The paraphrase for this work was done by Anna Kustikova-Veilande, who acted both as curator and artist. Kustikova-Veilande has brought in a broader network of associations without clinging to the superficial similarities of the subject (as do the majority of the other paraphrases). Her version of ‘Journey in Space’ is a series of eight photographs entitled Pēdējais kosmonauts? (‘The Last Cosmonaut?’) featuring portraits of eight boys and supplemented with the transcript of a short interview. The children’s answers to the question “What will you be when you grow up?” frequently reveal “the contemporary cosmonaut”, that is, “dream professions” as touted by the mass media. A certain interest in the subject is evident in Alīna Zubkova’s comment on Jānis Pauļuks’ (1906–1984) painting Felicita ar avīzi (‘Felicita with Newspaper‘, 1945), although the narrative breaks off in the most interesting place, soon after the phrase “a newspaper appears in a painting which features a beautiful nude woman – this is an unusual combination of motifs”. It certainly is possible to get many more facts, to draw analogies with other artists’ works etc.. The version by Krišjānis Rijnieks, Kailums masām (‘Nudity for the Masses’), again only plays on the subject matter: Rijnieks, too, presents a female nude with a newspaper, only that Cīņa [‘The Struggle’, a Communist Party paper] has been replaced by Diena. Auseklis Baušķenieks’ (1910–2007) painting Hokejs (‘Ice Hockey’, 1975) displays the artist’s own characteristic humour and critical observation. Līva Mišele Piešiņa in her interpretation emphasises the role of socio-critical comment (“it should be the time to sit down for a festive meal, but tonight is the night of the hockey game of the century: Moscow CSKA plays the New York Rangers. The last minutes of the extra time are ticking on, and it’s still a draw, 3 all. Will the Muscovites beat the capitalist Yankees!?”), but Elīna Poikāne in her sculptures Hokejs I and Hokejs II seems to expand the space of the painting by adding two more spectators. | |

Elīna Poikāne. Hockey I; Hockey II. Plastic, metal. 20x14x12; 22x11x13cm. 2010 | |

| On the whole, the Look How Nice!? exhibition gave an insight into at least one of the functions of a contemporary curator: a curator may add their contribution to the self-sufficient completeness of an art work, and become a co-author of an art event. To return to that “leap into the unknown” mentioned earlier in this article – in a conversation with the author of the idea Šelda Puķīte and art historians Anna Kustikova-Veilande, Iveta Damroze and Inese Kundziņa, we established that the LMA bachelors of art theory and history have their very own notions of the theoretical and practical aspects of a curator’s work (for example, “a curator assists artists and the public, too”; “art criticism can be objective”; “in Latvia, it is still possible to arrange a curator’s exhibition, as until now there haven’t been many of those”; “a curator reviews the situation in art, and, when putting together a thematic exhibition, can show something inspiring, something out-of-the-way, in addition in a manner that is not too sophisticated and can be understood by the ordinary person”). In recent years, a great deal of literature on curatorial practice has been produced in the most popular languages and sources are available, for example, in the library of the Centre for Contemporary Art as well as, partly, on the internet. As a summary, in answer to my question about studying the literature in the field, I quote Šelda Puķīte: “Practice is more important than theory”. It certainly is, for what is there to learn that could be put to good use in Latvia’s circumstances from, for example, curator Hans Ulrich Obrist and his book ‘A Brief His-tory of Curating’ (JRP Ringier, 2008)? It is Obrist who ranks first in the Art Review magazine ‘Power 100’ list of the art world’s most powerful figures for the year 2009 (www.artreview100.com). But Obrist and his equally renowned and influential colleagues work in some other world, which we go and visit only rarely. /Translator into English: Sarmīte Lietuviete/ | |

| go back | |